Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 May 2023

Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineagesAlejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559Flexibility in Aphid Endosymbiosis: Dual Symbioses Have Evolved Anew at Least Six TimesRecommended by Olivier Tenaillon based on reviews by Alex C. C. Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this intriguing study (Manzano-Marín et al. 2022) by Alejandro Manzano-Marin and his colleagues, the association between aphids and their symbionts is investigated through meta-genomic analysis of new samples. These associations have been previously described as leading to fascinating genomic evolution in the symbiont (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). The bacterial genomes exhibit a significant reduction in size and the range of functions performed. They typically lose the ability to produce many metabolites or biobricks created by the host, and instead, streamline their metabolism by focusing on the amino acids that the host cannot produce. This level of co-evolution suggests a stable association between the two partners. However, the new data suggests a much more complex pattern as multiple independent acquisitions of co-symbionts are observed. Co-symbiont acquisition leads to a partition of the functions carried out on the bacterial side, with the new co-symbiont taking over some of the functions previously performed by Buchnera. In most cases, the new co-symbiont also brings the ability to produce B1 vitamin. Various facultative symbiotic taxa are recruited to be co-symbionts, with the frequency of acquisition related to the bacterial niche and lifestyle. REFERENCES Manzano-Marín, Alejandro, Armelle Coeur D’acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, and Emmanuelle Jousselin. 2023. “Co-Obligate Symbioses Have Repeatedly Evolved across Aphids, but Partner Identity and Nutritional Contributions Vary across Lineages.” bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559. McCutcheon, John P., and Nancy A. Moran. 2012. “Extreme Genome Reduction in Symbiotic Bacteria.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670. | Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineages | Alejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Aphids are a large family of phloem-sap feeders. They typically rely on a single bacterial endosymbiont, <em>Buchnera aphidicola</em>, to supply them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. This association ... |  | Genome Evolution, Other, Species interactions | Olivier Tenaillon | 2022-11-16 10:13:37 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

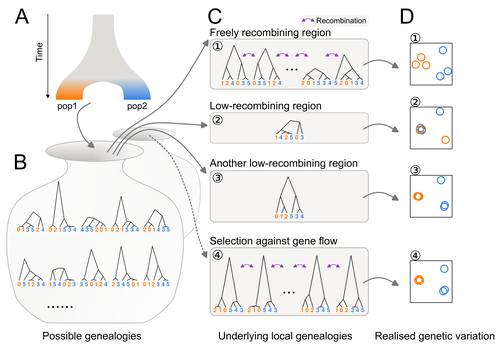

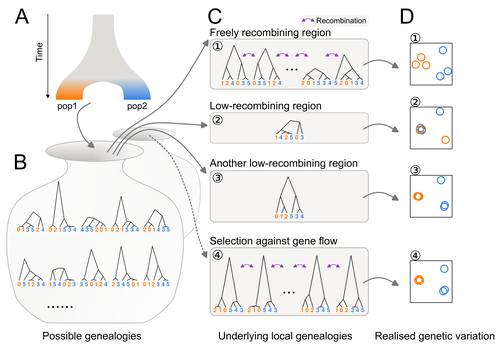

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

18 May 2020

The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequencesJulien Y. Dutheil, Karin Münch, Klaas Schotanus, Eva H. Stukenbrock and Regine Kahmann https://doi.org/10.1101/787044Some evolutionary insights into an accidental homing endonuclease passage from mitochondria to the nucleusRecommended by Sylvain Charlat based on reviews by Jan Engelstaedter and Yannick WurmNot all genetic elements composing genomes are there for the benefit of their carrier. Many have no consequences on fitness, or too mild ones to be eliminated by selection, and thus stem from neutral processes. Many others are indeed the product of selection, but one acting at a different level, increasing the fitness of some elements of the genome only, at the expense of the “organism” as a whole. These can be called selfish genetic elements, and come into a wide variety of flavours [1], illustrating many possible means to cheat with “fair” reproductive processes such as meiosis, and thus get overrepresented in the offspring of their hosts. Producing copies of itself through transposition is one such strategy; a very successful one indeed, explaining a large part of the genomic content of many organisms. Killing non carrier gametes following meiosis in heterozygous carriers is another one. Less know and less common is the ability of some elements to turn heterozygous carriers into homozygous ones, that will thus transmit the selfish elements to all offspring instead of half. This is achieved by nucleic sequences encoding so-called “Homing endonucleases” (HEs). These proteins tend to induce double strand breaks of DNA specifically in regions homologous to their own insertion sites. The recombination machinery is such that the intact homologous region, that is, the one carrying the HE sequence, is then used as a template for the reparation of the break, resulting in the effective conversion of a non-carrier allele into a carrier allele. Such elements can also occur in the mitochondrial genomes of organisms where mitochondria are not strictly transmitted by one parent only, offering mitochondrial HEs some opportunities for “homing” into new non carrier genomes. This is the case in yeasts, where HEs were first reported [2,3]. References [1] Burt, A., and Trivers, R. (2006). Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. Belknap Press. | The insertion of a mitochondrial selfish element into the nuclear genome and its consequences | Julien Y. Dutheil, Karin Münch, Klaas Schotanus, Eva H. Stukenbrock and Regine Kahmann | <p>Homing endonucleases (HE) are enzymes capable of cutting DNA at highly specific target sequences, the repair of the generated double-strand break resulting in the insertion of the HE-encoding gene ("homing" mechanism). HEs are present in all th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Sylvain Charlat | 2019-09-30 20:34:23 | View | |

05 Dec 2017

Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic dataEmeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/139147Predicting small ancestors using contemporary genomes of large mammalsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Bruce Rannala and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent methodological developments and increased genome sequencing efforts have introduced the tantalizing possibility of inferring ancestral phenotypes using DNA from contemporary species. One intriguing application of this idea is to exploit the apparent correlation between substitution rates and body size to infer ancestral species' body sizes using the inferred patterns of substitution rate variation among species lineages based on genomes of extant species [1]. References [1] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJP and Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 5–13. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss211 [2] Figuet E, Ballenghien M, Lartillot N and Galtier N. 2017. Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 of 4th December 2017. 139147. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data | Emeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Reconstructing ancestral characters on a phylogeny is an arduous task because the observed states at the tips of the tree correspond to a single realization of the underlying evolutionary process. Recently, it was proposed that ancestral traits... |  | Genome Evolution, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Bruce Rannala | 2017-05-18 15:28:58 | View | |

06 Oct 2017

Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebratesFrancisco J. Novo https://doi.org/10.1101/150482Combining molecular information on chromatin organisation with eQTLs and evolutionary conservation provides strong candidates for the evolution of gene regulation in mammalian brainsRecommended by Marc Robinson-Rechavi based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Charles DankoIn this manuscript [1], Francisco J. Novo proposes candidate non-coding genomic elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes. What is very nice about this study is the way in which public molecular data, including physical interaction data, is used to leverage recent advances in our understanding to molecular mechanisms of gene regulation in an evolutionary context. More specifically, evolutionarily conserved non coding sequences are combined with enhancers from the FANTOM5 project, DNAse hypersensitive sites, chromatin segmentation, ChIP-seq of transcription factors and of p300, gene expression and eQTLs from GTEx, and physical interactions from several Hi-C datasets. The candidate regulatory regions thus identified are linked to candidate regulated genes, and the author shows their potential implication in brain development. While the results are focused on a small number of genes, this allows to verify features of these candidates in great detail. This study shows how functional genomics is increasingly allowing us to fulfill the promises of Evo-Devo: understanding the molecular mechanisms of conservation and differences in morphology. References [1] Novo, FJ. 2017. Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 150482, ver. 4 of Sept 29th, 2017. doi: 10.1101/150482 | Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates | Francisco J. Novo | <p>Many non-coding regulatory elements conserved in vertebrates regulate the expression of genes involved in development and play an important role in the evolution of morphology through the rewiring of developmental gene networks. Available biolo... |  | Genome Evolution | Marc Robinson-Rechavi | Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Charles Danko | 2017-06-29 08:55:41 | View |

06 Sep 2022

Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonadsJulie Jaquiery, Jean-Christophe Simon, Stephanie Robin, Gautier Richard, Jean Peccoud, Helene Boulain, Fabrice Legeai, Sylvie Tanguy, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Gael Letrionnaire https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.453080Sex-biased gene expression is not tissue-specific in Pea AphidsRecommended by Charles Baer and Tanja Schwander based on reviews by Ann Kathrin Huylmans and 1 anonymous reviewerSexual antagonism (SA), wherein the fitness interests of the sexes do not align, is inherent to organisms with two (or more) sexes. SA leads to intra-locus sexual conflict, where an allele that confers higher fitness in one sex reduces fitness in the other [1, 2]. This situation leads to what has been referred to as "gender load", resulting from the segregation of SA alleles in the population. Gender load can be reduced by the evolution of sex-specific (or sex-biased) gene expression. A specific prediction is that gene-duplication can lead to sub- or neo-functionalization, in which case the two duplicates partition the function in the different sexes. The conditions for invasion by a SA allele differ between sex-chromosomes and autosomes, leading to the prediction that (in XY or XO systems) the X should accumulate recessive male-favored alleles and dominant female-favored alleles; similar considerations apply in ZW systems ([3, but see 4]. Aphids present an interesting special case, for several reasons: they have XO sex-determination, and three distinct reproductive morphs (sexual females, parthenogenetic females, and males). Previous theoretical work by the lead author predict that the X should be optimized for male function, which was borne out by whole-animal transcriptome analysis [5]. Here [6], the authors extend that work to investigate “tissue”-specific (heads, legs and gonads), sex-specific gene expression. They argue that, if intra-locus SA is the primary driver of sex-biased gene expression, it should be generally true in all tissues. They set up as an alternative the possibility that sex-biased gene expression could also be driven by dosage compensation. They cite references supporting their argument that "dosage compensation (could be) stronger in the brain", although the underlying motivation for that argument appears to be based on empirical evidence rather than theoretical predictions. At any rate, the results are clear: all tissues investigated show masculinization of the X. Further, X-linked copies of gene duplicates were more frequently male-biased than duplicated autosomal genes or X-linked single-copy genes. To sum up, this is a nice empirical study with clearly interpretable (and interpreted) results, the most obvious of which is the greater sex-biased expression in sexually-dimorphic tissues. Unfortunately, as the authors emphasize, there is no general theory by which SA, variable dosage-compensation, and meiotic sex chromosome inactivation can be integrated in a predictive framework. It is to be hoped that empirical studies such as this one will motivate deeper and more general theoretical investigations. References [1] Rice WR, Chippindale AK (2001) Intersexual ontogenetic conflict. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 14: 685-693. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00319.x [2] Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF (2009) Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol Evol 24: 280-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005 [3] Rice WR. (1984) Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38: 735-742. https://doi.org/10.1086/595754 [4] Fry JD (2010) The genomic location of sexually antagonistic variation: some cautionary comments. Evolution 64: 1510-1516. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1558-5646.2009.00898.x [5] Jaquiéry J, Rispe C, Roze D, Legeai F, Le Trionnaire G, Stoeckel S, et al. (2013) Masculinization of the X Chromosome in the Pea Aphid. PLoS Genetics 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003690 [6] Jaquiéry J, Simon J-C, Robin S, Richard G, Peccoud J, Boulain H, Legeai F, Tanguy S, Prunier-Leterme N, Le Trionnaire G (2022) Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonads. bioRxiv, 2021.08.13.453080, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.453080 | Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonads | Julie Jaquiery, Jean-Christophe Simon, Stephanie Robin, Gautier Richard, Jean Peccoud, Helene Boulain, Fabrice Legeai, Sylvie Tanguy, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Gael Letrionnaire | <p>Males and females share essentially the same genome but differ in their optimal values for many phenotypic traits, which can result in intra-locus conflict between the sexes. Aphids display XX/X0 sex chromosomes and combine unusual X chromosome... |  | Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Charles Baer | 2021-08-16 08:56:08 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host speciesFanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417What makes a parasite successful? Parasitoid wasp venoms evolve rapidly in a host-specific mannerRecommended by Élio Sucena based on reviews by Simon Fellous, alexandre leitão and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitoid wasps have developed different mechanisms to increase their parasitic success, usually at the expense of host survival (Fellowes and Godfray, 2000). Eggs of these insects are deposited inside the juvenile stages of their hosts, which in turn deploy several immune response strategies to eliminate or disable them (Yang et al., 2020). Drosophila melanogaster protects itself against parasitoid attacks through the production of specific elongated haemocytes called lamellocytes which form a capsule around the invading parasite (Lavine and Strand, 2002; Rizki and Rizki, 1992) and the subsequent activation of the phenol-oxidase cascade leading to the release of toxic radicals (Nappi et al., 1995). On the parasitoid side, robust responses have evolved to evade host immune defenses as for example the Drosophila-specific endoparasite Leptopilina boulardi, which releases venom during oviposition that modifies host behaviour (Varaldi et al., 2006) and inhibits encapsulation (Gueguen et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012).

References Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Gatti, J.-L., Colinet, D. and Poirié, M. (2021) Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species. bioRxiv, 2020.10.24.353417, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417 Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Kremmer, L., Rebuf, C., Gatti, J.-L., Malausa, T., Colinet, D., Poiré, M. and Léne. (2019). Rapid and Differential Evolution of the Venom Composition of a Parasitoid Wasp Depending on the Host Strain. Toxins, 11(629). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11110629 Colinet, D., Deleury, E., Anselme, C., Cazes, D., Poulain, J., Azema-Dossat, C., Belghazi, M., Gatti, J. L. and Poirié, M. (2013). Extensive inter- and intraspecific venom variation in closely related parasites targeting the same host: The case of Leptopilina parasitoids of Drosophila. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43(7), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.010 Colinet, D., Dubuffet, A., Cazes, D., Moreau, S., Drezen, J. M. and Poirié, M. (2009). A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 33(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013 Fellowes, M. D. E. and Godfray, H. C. J. (2000). The evolutionary ecology of resistance to parasitoids by Drosophila. Heredity, 84(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00685.x Gueguen, G., Rajwani, R., Paddibhatla, I., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2011). VLPs of Leptopilina boulardi share biogenesis and overall stellate morphology with VLPs of the heterotoma clade. Virus Research, 160(1–2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.005 Lavine, M. D. and Strand, M. R. (2002). Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32(10), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9 Martinez, J., Duplouy, A., Woolfit, M., Vavre, F., O’Neill, S. L. and Varaldi, J. (2012). Influence of the virus LbFV and of Wolbachia in a host-parasitoid interaction. PloS One, 7(4), e35081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035081 Nappi, A. J., Vass, E., Frey, F. and Carton, Y. (1995). Superoxide anion generation in Drosophila during melanotic encapsulation of parasites. European Journal of Cell Biology, 68(4), 450–456. Poirié, M., Colinet, D. and Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004 Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 16(2–3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z Schlenke, T. A., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathogens, 3(10), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030158 Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology, 132(Pt 6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009930 Yang, L., Qiu, L., Fang, Q., Stanley, D. W. and Gong‐Yin, Y. (2020). Cellular and humoral immune interactions between Drosophila and its parasitoids. Insect Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12863

| Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species | Fanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié | <p>Female endoparasitoid wasps usually inject venom into hosts to suppress their immune response and ensure offspring development. However, the parasitoid’s ability to evolve towards increased success on a given host simultaneously with the evolut... |  | Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Élio Sucena | 2020-10-26 15:00:55 | View | |

31 Jan 2018

Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approachSusan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon https://doi.org/10.1101/118695A new statistical tool to identify the determinant of parallel evolutionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Bastien Boussau and 1 anonymous reviewerIn experimental evolution followed by whole genome resequencing, parallel evolution, defined as the increase in frequency of identical changes in independent populations adapting to the same environment, is often considered as the product of similar selection pressures and the parallel changes are interpreted as adaptive. References [1] Bailey SF, Guo Q and Bataillon T (2018) Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach. bioRxiv 118695, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/118695 [2] Lang GI, Rice DP, Hickman, MJ, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Botstein D, and Desai MM (2013) Pervasive genetic hitchhiking and clonal interference in forty evolving yeast populations. Nature 500: 571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature12344 | Identifying drivers of parallel evolution: A regression model approach | Susan F Bailey, Qianyun Guo, Thomas Bataillon | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100045). Parallel evolution, defined as identical changes arising in independent populations, is often attributed... |  | Experimental Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-03-22 14:54:48 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks?Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.550272How to survive the mutational meltdown: lessons from plant RNA virusesRecommended by Kavita Jain based on reviews by Brent Allman, Ana Morales-Arce and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough most mutations are deleterious, the strongly deleterious ones do not spread in a very large population as their chance of fixation is very small. Another mechanism via which the deleterious mutations can be eliminated is via recombination or sexual reproduction. However, in a finite asexual population, the subpopulation without any deleterious mutation will eventually acquire a deleterious mutation resulting in the reduction of the population size or in other words, an increase in the genetic drift. This, in turn, will lead the population to acquire deleterious mutations at a faster rate eventually leading to a mutational meltdown. This irreversible (or, at least over some long time scales) accumulation of deleterious mutations is especially relevant to RNA viruses due to their high mutation rate, and while the prior work has dealt with bacteriophages and RNA viruses, the study by Lafforgue et al. [1] makes an interesting contribution to the existing literature by focusing on plants. In this study, the authors enquire how despite the repeated increase in the strength of genetic drift, how the RNA viruses manage to survive in plants. Following a series of experiments and some numerical simulations, the authors find that as expected, after severe bottlenecks, the fitness of the population decreases significantly. But if the bottlenecks are followed by population expansion, the Muller’s ratchet can be halted due to the genetic diversity generated during population growth. They hypothesize this mechanism as a potential way by which the RNA viruses can survive the mutational meltdown. As a theoretician, I find this investigation quite interesting and would like to see more studies addressing, e.g., the minimum population growth rate required to counter the potential extinction for a given bottleneck size and deleterious mutation rate. Of course, it would be interesting to see in future work if the hypothesis in this article can be tested in natural populations. References [1] Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena (2024) How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology | How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? | Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena | <p>Muller's ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in small populations, resulting in a decline in overall fitness. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in experiments involving microorganisms, including ... | Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution | Kavita Jain | 2023-08-04 09:37:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer