Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Apr 2017

POSTPRINT

Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoesLequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111Vectors as motors (of virus evolution)Recommended by Frédéric Fabre and Benoit MouryMany viruses are transmitted by biological vectors, i.e. organisms that transfer the virus from one host to another. Dengue virus (DENV) is one of them. Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has rapidly spread around the world since the 1940s. One recent estimate indicates 390 million dengue infections per year [1]. As many arthropod-borne vertebrate viruses, DENV has to cross several anatomical barriers in the vector, to multiply in its body and to invade its salivary glands before getting transmissible. As a consequence, vectors are not passive carriers but genuine hosts of the viruses that potentially have important effects on the composition of virus populations and, ultimately, on virus epidemiology and virulence. Within infected vectors, virus populations are expected to acquire new mutations and to undergo genetic drift and selection effects. However, the intensity of these evolutionary forces and the way they shape virus genetic diversity are poorly known. In their study, Lequime et al. [2] finely disentangled the effects of genetic drift and selection on DENV populations during their infectious cycle within mosquito (Aedes aegypti) vectors. They evidenced that the genetic diversity of viruses within their vectors is shaped by genetic drift, selection and vector genotype. The experimental design consisted in artificial acquisition of purified virus by mosquitoes during a blood meal. The authors monitored the diversity of DENV populations in Ae. aegypti individuals at different time points by high-throughput sequencing (HTS). They estimated the intensity of genetic drift and selection effects exerted on virus populations by comparing the DENV diversity at these sampling time points with the diversity in the purified virus stock (inoculum). Disentangling the effects of genetic drift and selection remains a methodological challenge because both evolutionary forces operate concomitantly and both reduce genetic diversity. However, selection reduces diversity in a reproducible manner among experimental replicates (here, mosquito individuals): the fittest variants are favoured at the expense of the weakest ones. In contrast, genetic drift reduces diversity in a stochastic manner among replicates. Genetic drift acts equally on all variants irrespectively of their fitness. The strength of genetic drift is frequently evaluated with the effective population size Ne: the lower Ne, the stronger the genetic drift [3]. The estimation of the effective population size of DENV populations by Lequime et al. [2] was based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were (i) present both in the inoculum and in the virus populations sampled at the different time points and (ii) that were neutral (or nearly-neutral) and therefore subjected to genetic drift only and insensitive to selection. As expected for viruses that possess small and constrained genomes, such neutral SNPs are extremely rare. Starting from a set of >1800 SNPs across the DENV genome, only three SNPs complied with the neutrality criteria and were enough represented in the sequence dataset for a precise Ne estimation. Using the method described by Monsion et al. [4], Lequime et al. [2] estimated Ne values ranging from 5 to 42 viral genomes (95% confidence intervals ranged from 2 to 161 founding viral genomes). Consequently, narrow bottlenecks occurred at the virus acquisition step, since the blood meal had allowed the ingestion of ca. 3000 infectious virus particles, on average. Interestingly, bottleneck sizes did not differ between mosquito genotypes. Monsion et al.’s [4] formula provides only an approximation of Ne. A corrected formula has been recently published [5]. We applied this exact Ne formula to the means and variances of the frequencies of the three neutral markers estimated before and after the bottlenecks (Table 1 in [2]), and nearly identical Ne estimates were obtained with both formulas. Selection intensity was estimated from the dN/dS ratio between the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rates using the HTS data on DENV populations. DENV genetic diversity increased following initial infection but was restricted by strong purifying selection during virus expansion in the midgut. Again, no differences were detected between mosquito genotypes. However and importantly, significant differences in DENV genetic diversity were detected among mosquito genotypes. As they could not be related to differences in initial genetic drift or to selection intensity, the authors raise interesting alternative hypotheses, including varying rates of de novo mutations due to differences in replicase fidelity or differences in the balancing selection regime. Interestingly, they also suggest that this observation could simply result from a methodological issue linked to the detection threshold of low-frequency SNPs. References [1] Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496: 504–7 doi: 10.1038/nature12060 [2] Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L. 2016. Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes. PloS Genetics 12: e1006111 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111 [3] Charlesworth B. 2009. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics 10: 195-205 doi: 10.1038/nrg2526 [4] Monsion B, Froissart R, Michalakis Y and Blanc S. 2008. Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization. PloS Pathogens 4: e1000174 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000174 [5] Thébaud G and Michalakis Y. 2016. Comment on ‘Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization’ by Monsion et al. (2008). PloS Pathogens 12: e1005512 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005512 | Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes | Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L | Due to their error-prone replication, RNA viruses typically exist as a diverse population of closely related genomes, which is considered critical for their fitness and adaptive potential. Intra-host demographic fluctuations that stochastically re... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frédéric Fabre | 2017-04-10 14:26:04 | View | |

22 Mar 2022

Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus CorbiculaVastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836Strange reproductive modes and population geneticsRecommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Arnaud Estoup, Simon Henry Martin and 2 anonymous reviewersThere are many organisms that are asexual or have unusual modes of reproduction. One such quasi-sexual reproductive mode is androgenesis, in which the offspring, after fertilization, inherits only the entire paternal nuclear genome. The maternal genome is ditched along the way. One group of organisms which shows this mode of reproduction are clams in the genus Corbicula, some of which are androecious, while others are dioecious and sexual. The study by Vastrade et al. (2022) describes population genetic patterns in these clams, using both nuclear and mitochondrial sequence markers. In contrast to what might be expected for an asexual lineage, there is evidence for significant genetic mixing between populations. In addition, there is high heterozygosity and evidence for polyploidy in some lineages. Overall, the picture is complicated! However, what is clear is that there is far more genetic mixing than expected. One possible mechanism by which this could occur is 'nuclear capture' where there is a mixing of maternal and paternal lineages after fertilization. This can sometimes occur as a result of hybridization between 'species', leading to further mixing of divergent lineages. Thus the group is clearly far from an ancient asexual lineage - recombination and mixing occur with some regularity. The study also analyzed recent invasive populations in Europe and America. These had reduced genetic diversity, but also showed complex patterns of allele sharing suggesting a complex origin of the invasive lineages. In the future, it will be exciting to apply whole genome sequencing approaches to systems such as this. There are challenges in interpreting a handful of sequenced markers especially in a system with polyploidy and considerable complexity, and whole-genome sequencing could clarify some of the outstanding questions, Overall, this paper highlights the complex genetic patterns that can result through unusual reproductive modes, which provides a challenge for the field of population genetics and for the recognition of species boundaries. References Vastrade M, Etoundi E, Bournonville T, Colinet M, Debortoli N, Hedtke SM, Nicolas E, Pigneur L-M, Virgo J, Flot J-F, Marescaux J, Doninck KV (2022) Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. bioRxiv, 590836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836 | Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula | Vastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. | <p style="text-align: justify;">“Occasional” sexuality occurs when a species combines clonal reproduction and genetic mixing. This strategy is predicted to combine the advantages of both asexuality and sexuality, but its actual consequences on the... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Chris Jiggins | 2019-03-29 15:42:56 | View | |

20 Dec 2017

Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiationNicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias 10.1101/148189The influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification, revealed by Neotropical butterfliesRecommended by Richard H Ree based on reviews by Delano Lewis and 1 anonymous reviewerThe influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification is a hot topic in biogeography. Of central interest are questions about where, when, and how fast lineages proliferated, suffered extinction, and migrated in response to tectonic events, the waxing and waning of dominant biomes, etc. In this context, the dynamic conditions of the Miocene have received much attention, from studies of many clades and biogeographic regions. Here, Chazot et al. [1] present an exemplary analysis of butterflies (tribe Ithomiini) in the Neotropics, examining their diversification across the Andes and Amazon. They infer sharp contrasts between these regions in the late Miocene: accelerated diversification during orogeny of the Andes, and greater extinction in the Amazon associated during the Pebas system, with interchange and local diversification increasing following the Pebas during the Pliocene. References [1] Chazot N, Willmott KR, Lamas G, Freitas AVL, Piron-Prunier F, Arias CF, Mallet J, De-Silva DL and Elias M. 2017. Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation. BioRxiv 148189, ver 4 of 19th December 2017. doi: 10.1101/148189 [2] Xing Y, and Ree RH. 2017. Uplift-driven diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a temperate biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114: E3444-E3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616063114 | Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation | Nicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias | The Neotropical region has experienced a dynamic landscape evolution throughout the Miocene, with the large wetland Pebas occupying western Amazonia until 11-8 my ago and continuous uplift of the Andes mountains along the western edge of South Ame... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Richard H Ree | 2017-06-12 11:55:14 | View | |

05 Jun 2018

Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species poolsJoaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal https://doi.org/10.1101/149617Recent assembly of European biogeographic species poolRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBiodiversity is unevenly distributed over time, space and the tree of life [1]. The fact that regions are richer than others as exemplified by the latitudinal diversity gradient has fascinated biologists as early as the first explorers travelled around the world [2]. Provincialism was one of the first general features of land biotic distributions noted by famous nineteenth century biologists like the phytogeographers J.D. Hooker and A. de Candolle, and the zoogeographers P.L. Sclater and A.R. Wallace [3]. When these explorers travelled among different places, they were struck by the differences in their biotas (e.g. [4]). The limited distributions of distinctive endemic forms suggested a history of local origin and constrained dispersal. Much biogeographic research has been devoted to identifying areas where groups of organisms originated and began their initial diversification [3]. Complementary efforts found evidence of both historical barriers that blocked the exchange of organisms between adjacent regions and historical corridors that allowed dispersal between currently isolated regions. The result has been a division of the Earth into a hierarchy of regions reflecting patterns of faunal and floral similarities (e.g. regions, subregions, provinces). Therefore a first ensuing question is: “how regional species pools have been assembled through time and space?”, which can be followed by a second question: “what are the ecological and evolutionary processes leading to differences in species richness among species pools?”. To address these questions, the study of Calatayud et al. [5] developed and performed an interesting approach relying on phylogenetic data to identify regional and sub-regional pools of European beetles (using the iconic ground beetle genus Carabus). Specifically, they analysed the processes responsible for the assembly of species pools, by comparing the effects of dispersal barriers, niche similarities and phylogenetic history. They found that Europe could be divided in seven modules that group zoogeographically distinct regions with their associated faunas, and identified a transition zone matching the limit of the ice sheets at Last Glacial Maximum (19k years ago). Deviance of species co-occurrences across regions, across sub-regions and within each region was significantly explained, primarily by environmental niche similarity, and secondarily by spatial connectivity, except for northern regions. Interestingly, southern species pools are mostly separated by dispersal barriers, whereas northern species pools are mainly sorted by their environmental niches. Another important finding of Calatayud et al. [5] is that most phylogenetic structuration occurred during the Pleistocene, and they show how extreme recent historical events (Quaternary glaciations) can profoundly modify the composition and structure of geographic species pools, as opposed to studies showing the role of deep-time evolutionary processes. The study of biogeographic assembly of species pools using phylogenies has never been more exciting and promising than today. Catalayud et al. [5] brings a nice study on the importance of Pleistocene glaciations along with geographical barriers and niche-based processes in structuring the regional faunas of European beetles. The successful development of powerful analytical tools in recent years, in conjunction with the rapid and massive increase in the availability of biological data (including molecular phylogenies, fossils, georeferrenced occurrences and ecological traits), will allow us to disentangle complex evolutionary histories. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and methodological shortcomings, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and biotic triggers are intertwined on shaping the Earth’s stupendous biological diversity. I hope that the Catalayud et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) will help movement in that direction, and that it will provide interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions. Applied to a European beetle radiation, they were able to tease apart the relative contributions of biotic (niche-based processes) versus abiotic (geographic barriers and climate change) factors. References [1] Rosenzweig ML. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools | Joaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal | <p>Despite the description of bioregions dates back from the origin of biogeography, the processes originating their associated species pools have been seldom studied. Ancient historical events are thought to play a fundamental role in configuring... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2017-06-14 07:30:32 | View | |

03 Jun 2018

Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive conceptThomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet https://doi.org/10.1101/276675Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewerThe increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment. In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model. The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies. The authors highlight and explain the following points: Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations. References [1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675 | Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View | |

11 Jul 2022

Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitismLeo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759Give them some space: how spatial structure affects the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosisRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers

The evolution of mutualistic symbiosis is a puzzle that has fascinated evolutionary ecologist for quite a while. Data on transitions between symbiotic bacterial ways of life has evidenced shifts from mutualism towards parasitism and vice versa (Sachs et al., 2011), so there does not seem to be a strong determinism on those transitions. From the host’s perspective, mutualistic symbiosis implies at the very least some form of immune tolerance, which can be costly (e.g. Sorci, 2013). Empirical approaches thus raise very important questions: How can symbiosis turn from parasitism into mutualism when it seemingly needs such a strong alignment of selective pressures on both the host and the symbiont? And yet why is mutualistic symbiosis so widespread and so important to the evolution of macro-organisms (Margulis, 1998)? While much of the theoretical literature on the evolution of symbiosis and mutualism has focused on either the stability of such relationships when non-mutualists can invade the host-symbiont system (e.g. Ferrière et al., 2007) or the effect of the mode of symbiont transmission on the evolutionary dynamics of mutualism (e.g. Genkai-Kato and Yamamura, 1999), the question remains whether and under which conditions parasitic symbiosis can turn into mutualism in the first place. Earlier results suggested that spatial demographic heterogeneity between host populations could be the leading determinant of evolution towards mutualism or parasitism (Hochberg et al., 2000). Here, Ledru et al. (2022) investigate this question in an innovative way by simulating host-symbiont evolutionary dynamics in a spatially explicit context. Their hypothesis is intuitive but its plausibility is difficult to gauge without a model: Does the evolution towards mutualism depend on the ability of the host and symbiont to evolve towards close-range dispersal in order to maintain clusters of efficient host-symbiont associations, thus outcompeting non-mutualists? I strongly recommend reading this paper as the results obtained by the authors are very clear: competition strength and the cost of dispersal both affect the likelihood of the transition from parasitism to mutualism, and once mutualism has set in, symbiont trait values clearly segregate between highly dispersive parasites and philopatric mutualists. The demonstration of the plausibility of their hypothesis is accomplished with brio and thoroughness as the authors also examine the conditions under which the transition can be reversed, the impact of the spatial range of competition and the effect of mortality. Since high dispersal cost and strong, long-range competition appear to be the main factors driving the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosis, now is the time for empiricists to start investigating this question with spatial structure in mind. References Ferrière, R., Gauduchon, M. and Bronstein, J. L. (2007) Evolution and persistence of obligate mutualists and exploiters: competition for partners and evolutionary immunization. Ecology Letters, 10, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01008.x Genkai-Kato, M. and Yamamura, N. (1999) Evolution of mutualistic symbiosis without vertical transmission. Theoretical Population Biology, 55, 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1998.1407 Hochberg, M. E., Gomulkiewicz, R., Holt, R. D. and Thompson, J. N. (2000) Weak sinks could cradle mutualistic symbioses - strong sources should harbour parasitic symbioses. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13, 213-222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00157.x Ledru L, Garnier J, Rohr M, Noûs C and Ibanez S (2022) Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism. bioRxiv, 2021.08.18.456759, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759 Margulis, L. (1998) Symbiotic planet: a new look at evolution, Basic Books, Amherst. Sachs, J. L., Skophammer, R. G. and Regus, J. U. (2011) Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 10800-10807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100304108 Sorci, G. (2013) Immunity, resistance and tolerance in bird–parasite interactions. Parasite Immunology, 35, 350-361. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12047 | Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism | Leo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez | <p>The evolution of mutualism between hosts and initially parasitic symbionts represents a major transition in evolution. Although vertical transmission of symbionts during host reproduction and partner control both favour the stability of mutuali... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Francois Massol | 2021-08-20 12:25:40 | View | |

31 Oct 2022

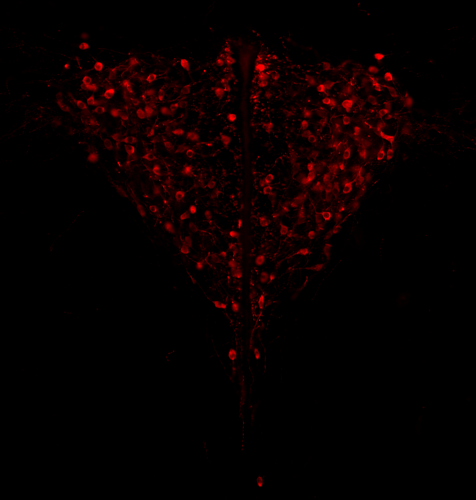

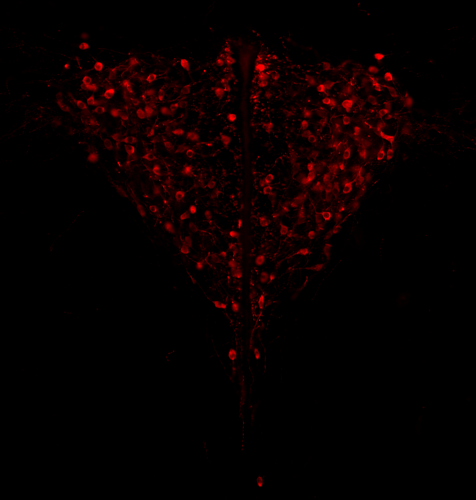

Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoidesLouise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174Effect of sex chromosomes on mammalian behaviour: a case study in pygmy miceRecommended by Gabriel Marais and Trine Bilde based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer

In mammals, it is well documented that sexual dimorphism and in particular sex differences in behaviour are fine-tuned by gonadal hormonal profiles. For example, in lemurs, where female social dominance is common, the level of testosterone in females is unusually high compared to that of other primate females (Petty and Drea 2015). Recent studies however suggest that gonadal hormones might not be the only biological factor involved in establishing sexual dimorphism, sex chromosomes might also play a role. The four core genotype (FCG) model and other similar systems allowing to decouple phenotypic and genotypic sex in mice have provided very convincing evidence of such a role (Gatewood et al. 2006; Arnold and Chen 2009; Arnold 2020a, 2020b). This however is a new field of research and the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sexually dimorphic behaviours has not been studied very much yet. Moreover, the FCG model has some limits. Sry, the male determinant gene on the mammalian Y chromosome might be involved in some sex differences in neuroanatomy, but Sry is always associated with maleness in the FCG model, and this potential role of Sry cannot be studied using this system. Heitzmann et al. have used a natural system to approach these questions. They worked on the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides, in which a modified X chromosome called X* can feminize X*Y individuals, which offers a great opportunity for elegant experiments on the effects of sex chromosomes versus hormones on behaviour. They focused on maternal care and compared pup retrieval, nest quality, and mother-pup interactions in XX, X*X and X*Y females. They found that X*Y females are significantly better at retrieving pups than other females. They are also much more aggressive towards the fathers than other females, preventing paternal care. They build nests of poorer quality but have similar interactions with pups compared to other females. Importantly, no significant differences were found between XX and X*X females for these traits, which points to an effect of the Y chromosome in explaining the differences between X*Y and other females (XX, X*X). Also, another work from the same group showed similar gonadal hormone levels in all the females (Veyrunes et al. 2022). Heitzmann et al. made a number of predictions based on what is known about the neuroanatomy of rodents which might explain such behaviours. Using cytology, they looked for differences in neuron numbers in the hypothalamus involved in the oxytocin, vasopressin and dopaminergic pathways in XX, X*X and X*Y females, but could not find any significant effects. However, this part of their work relied on very small sample sizes and they used virgin females instead of mothers for ethical reasons, which greatly limited the analysis. Interestingly, X*Y females have a higher reproductive performance than XX and X*X ones, which compensate for the cost of producing unviable YY embryos and certainly contribute to maintaining a high frequency of X* in many African pygmy mice populations (Saunders et al. 2014, 2022). X*Y females are probably solitary mothers contrary to other females, and Heitzmann et al. have uncovered a divergent female strategy in this species. Their work points out the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sex differences in behaviours. References Arnold AP (2020a) Sexual differentiation of brain and other tissues: Five questions for the next 50 years. Hormones and Behavior, 120, 104691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104691 Arnold AP (2020b) Four Core Genotypes and XY* mouse models: Update on impact on SABV research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 119, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.021 Arnold AP, Chen X (2009) What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001 Gatewood JD, Wills A, Shetty S, Xu J, Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS, Rissman EF (2006) Sex Chromosome Complement and Gonadal Sex Influence Aggressive and Parental Behaviors in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3743-05.2006 Heitzmann LD, Challe M, Perez J, Castell L, Galibert E, Martin A, Valjent E, Veyrunes F (2022) Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides. bioRxiv, 2022.04.05.487174, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174 Petty JMA, Drea CM (2015) Female rule in lemurs is ancestral and hormonally mediated. Scientific Reports, 5, 9631. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09631 Saunders PA, Perez J, Rahmoun M, Ronce O, Crochet P-A, Veyrunes F (2014) Xy Females Do Better Than the Xx in the African Pygmy Mouse, Mus Minutoides. Evolution, 68, 2119–2127. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12387 Saunders PA, Perez J, Ronce O, Veyrunes F (2022) Multiple sex chromosome drivers in a mammal with three sex chromosomes. Current Biology, 32, 2001-2010.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.03.029 Veyrunes F, Perez J, Heitzmann L, Saunders PA, Givalois L (2022) Separating the effects of sex hormones and sex chromosomes on behavior in the African pygmy mouse Mus minutoides, a species with XY female sex reversal. bioRxiv, 2022.07.11.499546. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.11.499546 | Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides | Louise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes | <p>Sexually dimorphic behaviours, such as parental care, have long been thought to be driven mostly, if not exclusively, by gonadal hormones. In the past two decades, a few studies have challenged this view, highlighting the direct influence of th... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2022-04-08 20:09:58 | View | |

14 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiMarianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055A valuable work lying at the crossroad of neuro-ethology, evolution and ecology in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiRecommended by Arnaud Estoup and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerAdaptations to a new ecological niche allow species to access new resources and circumvent competitors and are hence obvious pathways of evolutionary success. The evolution of agricultural pest species represents an important case to study how a species adapts, on various timescales, to a novel ecological niche. Among the numerous insects that are agricultural pests, the ability to lay eggs (or oviposit) in ripe fruit appears to be a recurrent scenario. Fruit flies (family Tephritidae) employ this strategy, and include amongst their members some of the most destructive pests (e.g., the olive fruit fly Bactrocera olea or the medfly Ceratitis capitata). In their ms, Karageorgi et al. [1] studied how Drosophila suzukii, a new major agricultural pest species that recently invaded Europe and North America, evolved the novel behavior of laying eggs into undamaged fresh fruit. The close relatives of D. suzukii lay their eggs on decaying plant substrates, and thus this represents a marked change in host use that links to substantial economic losses to the fruit industry. Although a handful of studies have identified genetic changes causing new behaviors in various species, the question of the evolution of behavior remains a largely uncharted territory. The study by Karageorgi et al. [1] represents an original and most welcome contribution in this domain for a non-model species. Using clever behavioral experiments to compare D. suzukii to several related Drosophila species, and complementing those results with neurogenetics and mutant analyses using D. suzukii, the authors nicely dissect the sensory changes at the origin of the new egg-laying behavior. The experiments they describe are easy to follow, richly illustrate through figures and images, and particularly well designed to progressively decipher the sensory bases driving oviposition of D. suzukii on ripe fruit. Altogether, Karageorgi et al.’s [1] results show that the egg-laying substrate preference of D. suzukii has considerably evolved in concert with its morphology (especially its enlarged, serrated ovipositor that enables females to pierce the skin of many ripe fruits). Their observations clearly support the view that the evolution of traits that make D. suzukii an agricultural pest included the modification of several sensory systems (i.e. mechanosensation, gustation and olfaction). These differences between D. suzukii and its close relatives collectively underlie a radical change in oviposition behavior, and were presumably instrumental in the expansion of the ecological niche of the species. The authors tentatively propose a multi-step evolutionary scenario from their results with the emergence of D. suzukii as a pest species as final outcome. Such formalization represents an interesting evolutionary model-framework that obviously would rely upon further data and experiments to confirm and refine some of the evolutionary steps proposed, especially the final and recent transition of D. suzukii from non-invasive to invasive species. References [1] Karageorgi M, Bräcker LB, Lebreton S, Minervino C, Cavey M, Siju KP, Grunwald Kadow IC, Gompel N, Prud’homme B. 2017. Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii. Current Biology, 27: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055 | Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii | Marianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme | The rise of a pest species represents a unique opportunity to address how species evolve new behaviors and adapt to novel ecological niches. We address this question by studying the egg-laying behavior of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive agricultur... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution | Arnaud Estoup | 2017-03-13 17:42:00 | View | |

18 Dec 2017

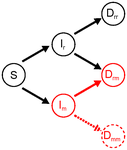

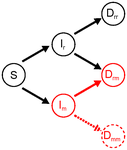

Co-evolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infectionsTsukushi Kamiya, Nicole Mideo, Samuel Alizon 10.1101/149211Two parasites, virulence and immunosuppression: how does the whole thing evolve?Recommended by Sara Magalhaes based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersHow parasite virulence evolves is arguably the most important question in both the applied and fundamental study of host-parasite interactions. Typically, this research area has been progressing through the formalization of the problem via mathematical modelling. This is because the question is a complex one, as virulence is both affected and affects several aspects of the host-parasite interaction. Moreover, the evolution of virulence is a problem in which ecology (epidemiology) and evolution (changes in trait values through time) are tightly intertwined, generating what is now known as eco-evolutionary dynamics. Therefore, intuition is not sufficient to address how virulence may evolve. References [1] Anderson RM and May RM. 1982. Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 1982. 85: 411–426. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000055360 [2] Kamiya T, Mideo N and Alizon S. 2017. Coevolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infections. bioRxiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol, 149211. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Co-evolution of virulence and immunosuppression in multiple infections | Tsukushi Kamiya, Nicole Mideo, Samuel Alizon | Many components of the host-parasite interaction have been shown to affect the way virulence, that is parasite induced harm to the host, evolves. However, co-evolution of multiple traits is often neglected. We explore how an immunosuppressive mech... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Sara Magalhaes | 2017-06-13 16:49:45 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks?Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.550272How to survive the mutational meltdown: lessons from plant RNA virusesRecommended by Kavita Jain based on reviews by Brent Allman, Ana Morales-Arce and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough most mutations are deleterious, the strongly deleterious ones do not spread in a very large population as their chance of fixation is very small. Another mechanism via which the deleterious mutations can be eliminated is via recombination or sexual reproduction. However, in a finite asexual population, the subpopulation without any deleterious mutation will eventually acquire a deleterious mutation resulting in the reduction of the population size or in other words, an increase in the genetic drift. This, in turn, will lead the population to acquire deleterious mutations at a faster rate eventually leading to a mutational meltdown. This irreversible (or, at least over some long time scales) accumulation of deleterious mutations is especially relevant to RNA viruses due to their high mutation rate, and while the prior work has dealt with bacteriophages and RNA viruses, the study by Lafforgue et al. [1] makes an interesting contribution to the existing literature by focusing on plants. In this study, the authors enquire how despite the repeated increase in the strength of genetic drift, how the RNA viruses manage to survive in plants. Following a series of experiments and some numerical simulations, the authors find that as expected, after severe bottlenecks, the fitness of the population decreases significantly. But if the bottlenecks are followed by population expansion, the Muller’s ratchet can be halted due to the genetic diversity generated during population growth. They hypothesize this mechanism as a potential way by which the RNA viruses can survive the mutational meltdown. As a theoretician, I find this investigation quite interesting and would like to see more studies addressing, e.g., the minimum population growth rate required to counter the potential extinction for a given bottleneck size and deleterious mutation rate. Of course, it would be interesting to see in future work if the hypothesis in this article can be tested in natural populations. References [1] Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena (2024) How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology | How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? | Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena | <p>Muller's ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in small populations, resulting in a decline in overall fitness. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in experiments involving microorganisms, including ... | Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution | Kavita Jain | 2023-08-04 09:37:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer