Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Nov 2020

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mitesMiguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilitiesRecommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewerCytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020). References Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543 | Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View | ||

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS 10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in pollinat... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

12 Jul 2017

Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costlySalomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães 10.1101/113274The pros and cons of mating with strangersRecommended by Vincent Calcagno based on reviews by Joël Meunier and Michael D Greenfield

Interspecific matings are by definition rare events in nature, but when they occur they can be very important, and not only because they might condition gene flow between species. Even when such matings have no genetic consequence, for instance if they do not yield any fertile hybrid offspring, they can still have an impact on the population dynamics of the species involved [1]. Such atypical pairings between heterospecific partners are usually regarded as detrimental or undesired; as they interfere with the occurrence or success of intraspecific matings, they are expected to cause a decline in absolute fitness. References [1] Gröning J. & Hochkirch A. 2008. Reproductive interference between animal species. The Quarterly Review of Biology 83: 257-282. doi: 10.1086/590510 [2] Clemente SH, Santos I, Ponce AR, Rodrigues LR, Varela SAM & Magalhaes S. 2017 Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly. bioRxiv 113274, ver. 4 of the 30th of June 2017. doi: 10.1101/113274 | Despite reproductive interference, the net outcome of reproductive interactions among spider mite species is not necessarily costly | Salomé H. Clemente, Inês Santos, Rita Ponce, Leonor R. Rodrigues, Susana A. M. Varela and Sara Magalhães | Reproductive interference is considered a strong ecological force, potentially leading to species exclusion. This supposes that the net effect of reproductive interactions is strongly negative for one of the species involved. Testing this requires... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Vincent Calcagno | 2017-03-06 11:48:08 | View | |

19 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptationKoyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T 10.1111/jeb.12653Megacicadas show a temperature-mediated converse Bergmann cline in body size (larger in the warmer south) but no body size difference between 13- and 17-year species pairsRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Thomas FlattPeriodical cicadas are a very prominent insect group in North America that are known for their large size, good looks, and loud sounds. However, they are probably known best to evolutionary ecologists because of their long juvenile periods of 13 or 17 years (prime numbers!), which they spend in the ground. Multiple related species living in the same area are often coordinated in emerging as adults during the same year, thereby presumably swamping any predators specialized on eating them. Reference [1] Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T. 2015. Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12653 | Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation | Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T | Seven species in three species groups (Decim, Cassini and Decula) of periodical cicadas (*Magicicada*) occupy a wide latitudinal range in the eastern United States. To clarify how adult body size, a key trait affecting fitness, varies geographical... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Macroevolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Speciation | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2016-12-19 10:39:22 | View | |

24 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genomeSébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux 10.1073/pnas.1608979113A newly evolved W(olbachia) sex chromosome in pillbug!Recommended by Gabriel Marais and Sylvain CharlatIn some taxa such as fish and arthropods, closely related species can have different mechanisms of sex determination and in particular different sex chromosomes, which implies that new sex chromosomes are constantly evolving [1]. Several models have been developed to explain this pattern but empirical data are lacking and the causes of the fast sex chromosome turn over remain mysterious [2-4]. Leclerq et al. [5] in a paper that just came out in PNAS have focused on one possible explanation: Wolbachia. This widespread intracellular symbiont of arthropods can manipulate its host reproduction in a number of ways, often by biasing the allocation of resources toward females, the transmitting sex. Perhaps the most spectacular example is seen in pillbugs, where Wolbachia commonly turns infected males into females, thus doubling its effective transmission to grandchildren. Extensive investigations on this phenomenon were initiated 30 years ago in the host species Armadillidium vulgare. The recent paper by Leclerq et al. beautifully validates an hypothesis formulated in these pioneer studies [6], namely, that a nuclear insertion of the Wolbachia genome caused the emergence of new female determining chromosome, that is, a new sex chromosome. Many populations of A. vulgare are infected by the feminising Wolbachia strain wVulC, where the spread of the bacterium has also induced the loss of the ancestral female determining W chromosome (because feminized ZZ individuals produce females without transmitting any W). In these populations, all individuals carry two Z chromosomes, so that the bacterium is effectively the new sex-determining factor: specimens that received Wolbachia from their mother become females, while the occasional loss of Wolbachia from mothers to eggs allows the production of males. Intriguingly, studies from natural populations also report that some females are devoid both of Wolbachia and the ancestral W chromosome, suggesting the existence of new female determining nuclear factor, the hypothetical “f element”. Leclerq et al. [5] found the f element and decrypted its origin. By sequencing the genome of a strain carrying the putative f element, they found that a nearly complete wVulC genome got inserted in the nuclear genome and that the chromosome carrying the insertion has effectively become a new W chromosome. The insertion is indeed found only in females, PCRs and pedigree analysis tell. Although the Wolbachia-derived gene(s) that became sex-determining gene(s) remain to be identified among many possible candidates, the genomic and genetic evidence are clear that this Wolbachia insertion is determining sex in this pillbug strain. Leclerq et al. [5] also found that although this insertion is quite recent, many structural changes (rearrangements, duplications) have occurred compared to the wVulC genome, which study will probably help understand which bacterial gene(s) have retained a function in the nucleus of the pillbug. Also, in the future, it will be interesting to understand how and why exactly the nuclear inserted Wolbachia rose in frequency in the pillbug population and how the cytoplasmic Wolbachia was lost, and to tease apart the roles of selection and drift in this event. We highly recommend this paper, which provides clear evidence that Wolbachia has caused sex chromosome turn over in one species, opening the conjecture that it might have done so in many others. References [1] Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, Hahn MW, Kitano J, Mayrose I, Ming R, Perrin N, Ross L, Valenzuela N, Vamosi JC. 2014. Tree of Sex Consortium. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biology 12: e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 [2] van Doorn GS, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 449: 909-912. doi: 10.1038/nature06178 [3] Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Grève P. 2011. The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends in Genetics 27: 332-341. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.002 [4] Blaser O, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2014. Sex-chromosome turnovers: the hot-potato model. American Naturalist 183: 140-146. doi: 10.1086/674026 [5] Leclercq S, Thézé J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L, Grève P, Gilbert C, Cordaux R. 2016. Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 113: 15036-15041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608979113 [6] Legrand JJ, Juchault P. 1984. Nouvelles données sur le déterminisme génétique et épigénétique de la monogénie chez le crustacé isopode terrestre Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Génétique Sélection Evolution 16: 57–84. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-16-1-57 | Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome | Sébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux | Sex determination is an evolutionarily ancient, key developmental pathway governing sexual differentiation in animals. Sex determination systems are remarkably variable between species or groups of species, however, and the evolutionary forces und... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Gabriel Marais | 2017-01-13 15:15:51 | View | |

18 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an InsectAlem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564Culture in BumblebeesRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Jacques J. M. van AlphenThis is an original paper [1] addressing the question whether cultural transmission occurs in insects and studying the mechanisms of such transmission. Often, culture-like phenomena require relatively sophisticated learning mechanisms, for example imitation and/or teaching. In insects, seemingly complex processes of social information acquisition, can sometimes instead be mediated by relatively simple learning mechanisms suggesting that cultural processes may not necessarily require sophisticated learning abilities. An important quality of this paper is to describe neatly the experimental protocols used for such typically complex behavioural analyses, providing a detailed understanding of the results while it remains a joy to read. This becomes rare in high impact journals. In a clever experimental design, individual bumblebees are trained to pull an artificial flower from under a Plexiglas table to get access to a reward, by pulling a string attached to the flower. Individuals that have learnt this task are then shown to inexperienced bees while performing this task. This results in a large proportion of the inexperienced observers learning to pull the string and getting access to the reward. Finally, the authors could then document the spread of the string pulling skill amongst other workers in the colony. Even when the originally trained individuals had died, the skill of string-pulling persisted in the colony, as long as they were challenged with the task. This shows that cultural transmission takes place within a colony. The authors provide evidence that the transmission of this behavior among individuals relies on a mix of social learning by local enhancement (bees were attracted to the location where they had observed a demonstrator) and of non-social, individual learning (pulling the string is learned by trial and errors and not by direct imitation of the conspecific). Data also show that simple associative mechanisms are enough and that stimulus enhancement was involved (bees were attracted to the string when its location was concordant with that during prior observation). The cleverly designed experiments use a paradigm (string-pulling) which has often been used to investigate cognitive abilities in vertebrates. Comparison with such studies indicate that bees, in some aspects of their learning, may not be different from birds, dogs, or apes as they also relied on the perceptual feedback provided by their actions, resulting in target movement to learn string pulling. The results of the study suggest that the combination of relatively simple forms of social learning and trial-and-error learning can mediate the acquisition of new skills and that bumblebees possess the essential cognitive elements for cultural transmission and in a broader sense, that the capacity of culture may be present within most animals. Can we expect behavioural innovation such as string pulling to occur in nature? Bombus terrestris colonies can reach a total of several hundreds foragers. In the experiments, foragers needed on average 5 rounds of observations with different demonstrators to learn how to pull the string. As individuals forage in a meadow full of flowers and conspecifics, transmission of behavioural innovations by repeated observations shouldn’t strike us as something impossible. Would the behavior survive through the winter? Bumblebee colonies are seasonal in northern areas and in the Mediterranean area but tropical species persists for several years. In seasonal species, all the workers die before winter and only new queens overwinter. So there is no possibility for seasonal foragers to transmit the technique overwinter. Only queens could potentially transmit it to new foragers in spring. However flowers are different in autumn and spring. Therefore, what queens have learnt about flowers in autumn would unlikely be useful in spring (providing that they can remember it). However there is no reason why the technique couldn't be transmitted from a colony to another between spring to autumn. Such transmission of new behaviour would more easily persist in perennial social insect colonies, like honeybees. Importantly, the bees used in these experiments came from a company whose rearing conditions are unknown, and only a few colonies were used for each experiment. As learning ability has a genetic basis [2-3], colonies differ in their ability to learn [4]. In this regard, the authors showed variation between individual bumblebees and between bumblebee colonies in learning ability. Hence, we would wish to know more about the level of genetic diversity in the wild, and of genetic differentiation between tested colonies (were they independent replicates?), to extrapolate the results to what may happen in the wild. Excitingly, the authors found 2 true innovators among the >400 individuals that were tested at least once for 5 min who would solve such a task without stepwise training or observation of skilled demonstrators, showing that behavioural innovation can occur in very small numbers of individuals, provided that an ecological trigger is provided (food reward). Hence this study shows that all ingredients for the long proposed “social heredity” theory proposed by Baldwin in 1896 are available in this organism, suggesting that social transmission of behavioural innovations could technically act as an additional mechanism for adaptive evolution [5], next to genetic evolution that may take longer to produce adaptive evolution. The question remains whether the behavioural innovations are arising from standing genetic variation in the bees, or do not need a firm genetic background to appear. References [1] Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L. 2016. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PloS Biology 14:e1002564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564 [2] Mery F, Kawecki TJ. 2002. Experimental evolution of learning ability in fruit flies. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 99:14274-14279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371199 [3] Mery F, Belay AT, So AKC, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ. 2007. Natural polymorphism affecting learning and memory in Drosophila. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:13051-13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702923104 [4] Raine NE, Chittka L. 2008. The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumble-bees. Proceeding of the Royal Society of London 275: 803-808. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1652 [5] Baldwin JM. 1896. A New Factor in Evolution. American Naturalist 30:441-451 and 536-553. doi: 10.1086/276408 | Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an Insect | Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L | Social insects make elaborate use of simple mechanisms to achieve seemingly complex behavior and may thus provide a unique resource to discover the basic cognitive elements required for culture, i.e., group-specific behaviors that spread from “inn... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-01-18 10:49:03 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosisHusnik F, McCutcheon JP doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603910113Obligate dependence does not preclude changing partners in a Russian dolls symbiotic systemRecommended by Emmanuelle Jousselin and Fabrice VavreSymbiotic associations with bacterial partners have facilitated important evolutionary transitions in the life histories of eukaryotes. For instance, many insects have established long-term interactions with intracellular bacteria that provide them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. However, despite the high level of interdependency among organisms involved in endosymbiotic systems, examples of symbiont replacements along the evolutionary history of insect hosts are numerous.

In their paper, Husnik and McCutcheon [1] test the stability of symbiotic systems in a particularly imbricated Russian-doll type interaction, where one bacterium lives insides another bacterium, which itself lives inside insect cells. For their study, they chose representative species of mealybugs (Pseudococcidae), a species rich group of sap-feeding insects that hosts diverse and complex symbiotic systems. In species of the subfamily Pseudococcinae, data published so far suggest that the primary symbiont, a ß-proteobacterium named Tremblaya princeps, is supplemented by a second bacterial symbiont (a ϒ-proteobaterium) that lives within its cytoplasm; both participate to the metabolic pathways that provide essential amino acids and vitamins to their hosts. Here, Husnik and McCutcheon generate host and endosymbiont genome data for five phylogenetically divergent species of Pseudococcinae in order to better understand: 1) the evolutionary history of the symbiotic associations; 2) the metabolic roles of each partner, 3) the timing and origin of Horizontal Gene Transfers (HGT) between the hosts and their symbionts. Reference [1] Husnik F., McCutcheon JP. 2016. Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. PNAS 113: E5416-E5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603910113 | Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis | Husnik F, McCutcheon JP | Stable endosymbiosis of a bacterium into a host cell promotes cellular and genomic complexity. The mealybug *Planococcus citri* has two bacterial endosymbionts with an unusual nested arrangement: the γ-proteobacterium *Moranella endobia* lives in ... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Emmanuelle Jousselin | 2016-12-13 14:27:09 | View | |

31 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Human adaptation of Ebola virus during the West African outbreakUrbanowicz, R.A., McClure, C.P., Sakuntabhai, A., Sall, A.A., Kobinger, G., Müller, M.A., Holmes, E.C., Rey, F.A., Simon-Loriere, E., and Ball, J.K. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.013Ebola evolution during the 2013-2016 outbreakRecommended by Sylvain Gandon and Sébastien LionThe Ebola virus (EBOV) epidemic that started in December 2013 resulted in around 28,000 cases and more than 11,000 deaths. Since the emergence of the disease in Zaire in 1976 the virus had produced a number of outbreaks in Africa but until 2013 the reported numbers of human cases had never risen above 500. Could this exceptional epidemic size be due to the spread of a human-adapted form of the virus? The large mutation rate of the virus [1-2] may indeed introduce massive amounts of genetic variation upon which selection may act. Several earlier studies based on the accumulation of genome sequences sampled during the epidemic led to contrasting conclusions. A few studies discussed evidence of positive selection on the glycoprotein that may be linked to phenotypic variations on infectivity and/or immune evasion [3-4]. But the heterogeneity in the transmission of some lineages could also be due to environmental heterogeneity and/or stochasticity. Most studies could not rule out the null hypothesis of the absence of positive selection and human adaptation [1-2 and 5]. In a recent experimental study, Urbanowicz et al. [6] chose a different method to tackle this question. A phylogenetic analysis of genome sequences from viruses sampled in West Africa revealed the existence of two main lineages (one with a narrow geographic distribution in Guinea, and the other with a wider geographic distribution) distinguished by a single amino acid substitution in the glycoprotein of the virus (A82V), and of several sub-lineages characterised by additional substitutions. The authors used this phylogenetic data to generate a panel of mutant pseudoviruses and to test their ability to infect human and fruit bat cells. These experiments revealed that specific amino acid substitutions led to higher infectivity of human cells, including A82V. This increased infectivity on human cells was associated with a decreased infectivity in fruit bat cell cultures. Since fruit bats are likely to be the reservoir of the virus, this paper indicates that human adaptation may have led to a specialization of the virus to a new host. An accompanying paper in the same issue of Cell by Diehl et al. [7] reports results that confirm the trend identified by Urbanowicz et al. [6] and further indicate that the increased infectivity of A82V is specific for primate cells. Diehl et al. [7] also report some evidence for higher virulence of A82V in humans. In other words, the evolution of the virus may have led to higher abilities to infect and to kill its novel host. This work thus confirms the adaptive potential of RNA virus and the ability of Ebola to specialize to a novel host. In this context, the availability of an effective vaccine against the disease is particularly welcome [8]. The study of Urbanowicz et al. [6] is also remarkable because it illustrates the need of experimental approaches for the study of phenotypic variation when inference methods based on phylodynamics fail to extract a clear biological message. The analysis of genomic evolution is still in its infancy and there is a need for new theoretical developments to help detect more rapidly candidate mutations involved in adaptations to new environmental conditions. References [1] Gire, S.K., Goba, A., Andersen, K.G., Sealfon, R.S.G., Park, D.J., Kanneh, L., Jalloh, S., Momoh, M., Fullah, M., Dudas, G., et al. (2014). Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345, 1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657 | Human adaptation of Ebola virus during the West African outbreak | Urbanowicz, R.A., McClure, C.P., Sakuntabhai, A., Sall, A.A., Kobinger, G., Müller, M.A., Holmes, E.C., Rey, F.A., Simon-Loriere, E., and Ball, J.K. | The 2013–2016 outbreak of Ebola virus (EBOV) in West Africa was the largest recorded. It began following the cross-species transmission of EBOV from an animal reservoir, most likely bats, into humans, with phylogenetic analysis revealing the co-ci... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Species interactions | Sylvain Gandon | 2017-03-31 14:20:38 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

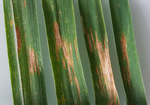

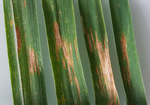

13 Nov 2017

Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen populationFrederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre 10.1101/151068The pace of pathogens’ adaptation to their host plantsRecommended by Benoit Moury based on reviews by Benoit Moury and 1 anonymous reviewerBecause of their shorter generation times and larger census population sizes, pathogens are usually ahead in the evolutionary race with their hosts. The risks linked to pathogen adaptation are still exacerbated in agronomy, where plant and animal populations are not freely evolving but depend on breeders and growers, and are usually highly genetically homogeneous. As a consequence, the speed of pathogen adaptation is crucial for agriculture sustainability. Unraveling the time scale required for pathogens’ adaptation to their hosts would notably greatly improve our estimation of the risks of pathogen emergence, the efficiency of disease control strategies and the design of epidemiological surveillance schemes. However, the temporal scale of pathogen evolution has received much less attention than its spatial scale [1]. In their study of a wheat fungal disease, Suffert et al. [2] reached contrasting conclusions about the pathogen adaptation depending on the time scale (intra- or inter-annual) and on the host genotype (sympatric or allopatric) considered, questioning the experimental assessment of this important problem. Suffert et al. [2] sampled two pairs of Zymoseptoria tritici (the causal agent of septoria leaf blotch) sub-populations in a bread wheat field plot, representing (i) isolates collected at the beginning or at the end of an epidemic in a single growing season (2009-2010 intra-annual sampling scale) and (ii) isolates collected from plant debris at the end of growing seasons in 2009 and in 2015 (inter-annual sampling scale). Then, they measured in controlled conditions two aggressiveness traits of the isolates of these four Z. tritici sub-populations, the latent period and the lesion size on leaves, on two wheat cultivars. One of the cultivars was considered as "sympatric" because it was at the source of the studied isolates and was predominant in the growing area before the experiment, whereas the other cultivar was considered as "allopatric" since it replaced the previous one and became predominant in the growing area during the sampling period. On the sympatric host, at the intra-annual scale, they observed a marginally-significant decrease in latent period and a significant decrease of the between-isolate variance for this trait, which are consistent with a selection of pathogen variants with an enhanced aggressiveness. In contrast, at the inter-annual scale, no difference in the mean or variance of aggressiveness trait values was observed on the sympatric host, suggesting a lack of pathogen adaptation. They interpreted the contrast between observations at the two time scales as the consequence of a trade-off for the pathogen between a gain of aggressiveness after several generations of asexual reproduction at the intra-annual scale and a decrease of the probability to reproduce sexually and to be transmitted from one growing season to the next. Indeed, at the end of the growing season, the most aggressive isolates are located on the upper leaves of plants, where the pathogen density and hence probably also the probability to reproduce sexually, is lower. On the allopatric host, the conclusion about the pathogen stability at the inter-annual scale was somewhat different, since a significant increase in the mean lesion size was observed (isolates corresponding to the intra-annual scale were not checked on the allopatric host). This shows the possibility for the pathogen to evolve at the inter-annual scale, for a given aggressiveness trait and on a given host. In conclusion, Suffert et al.’s [2] study emphasizes the importance of the experimental design in terms of sampling time scale and host genotype choice to analyze the pathogen adaptation to its host plants. It provides also an interesting scenario, at the crossroad of the pathogen’s reproduction regime, niche partitioning and epidemiological processes, to interpret these contrasted results. Pathogen adaptation to plant cultivars with major-effect resistance genes is usually fast, including in the wheat-Z. tritici system [3]. Therefore, this study will be of great help for future studies on pathogen adaptation to plant partial resistance genes and on strategies of deployment of such resistance at the landscape scale. References [2] Suffert F, Goyeau H, Sache I, Carpentier F, Gelisse S, Morais D and Delestre G. 2017. Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population. bioRxiv, 151068, ver. 3 of 12th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/151068 [3] Brown JKM, Chartrain L, Lasserre-Zuber P and Saintenac C. 2015. Genetics of resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici and applications to wheat breeding. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 79: 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.017 | Epidemiological trade-off between intra- and interannual scales in the evolution of aggressiveness in a local plant pathogen population | Frederic Suffert, Henriette Goyeau, Ivan Sache, Florence Carpentier, Sandrine Gelisse, David Morais, Ghislain Delestre | The efficiency of plant resistance to fungal pathogen populations is expected to decrease over time, due to its evolution with an increase in the frequency of virulent or highly aggressive strains. This dynamics may differ depending on the scale i... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Benoit Moury | 2017-06-23 21:04:54 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer