Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

04 Jun 2019

Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North AmericaJean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/550319Temperature variance, rather than mean, drives adaptation to local climateRecommended by Fabien Aubret based on reviews by Ben Phillips and Eric GangloffClimate change is impacting eco-systems worldwide and driving many populations to move, adapt or go extinct. It is increasingly appreciated, for example, that species may adjust their phenology in response to climate change, although empirical data is scarce. In this preprint [1], Tourneur and Meunier report an impressive sampling effort in which life-history traits were measured across introduced populations of earwig in North America. The authors examine whether variation in life-history across populations is correlated with aspects of the thermal climate experienced by each population: mean temperature and seasonality of temperature. They find some fascinating correlations between life-history and thermal climate; correlations with the seasonality of temperature, but not with mean temperature. This study provides relatively uncommon data, in the sense that where most of the literature looking at adaptation in animals in response to climate change has focused on physiological traits [2, 3], this study examines changes in life-history traits with time scales relevant to impending climate change, and provides a reasonable argument that this is adaptation, not just constraint. References [1] Tourneur, J.-C. and Meunier, J. (2019). Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America. BioRxiv, 550319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/550319 | Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America | Jean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier | <p>The recent development of human societies has led to major, rapid and often inexorable changes in the environment of most animal species. Over the last decades, a growing number of studies formulated predictions on the modalities of animal adap... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Fabien Aubret | 2019-02-15 09:12:11 | View | |

04 Mar 2021

Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiMJean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869Simulating bacterial evolution forward-in-timeRecommended by Frederic Bertels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersJean Cury and colleagues (2021) have developed a protocol to simulate bacterial evolution in SLiM. In contrast to existing methods that depend on the coalescent, SLiM simulates evolution forward in time. SLiM has, up to now, mostly been used to simulate the evolution of eukaryotes (Haller and Messer 2019), but has been adapted here to simulate evolution in bacteria. Forward-in-time simulations are usually computationally very costly. To circumvent this issue, bacterial population sizes are scaled down. One would now expect results to become inaccurate, however, Cury et al. show that scaled-down forwards simulations provide very accurate results (similar to those provided by coalescent simulators) that are consistent with theoretical expectations. Simulations were analyzed and compared to existing methods in simple and slightly more complex scenarios where recombination affects evolution. In all scenarios, simulation results from coalescent methods (fastSimBac (De Maio and Wilson 2017), ms (Hudson 2002)) and scaled-down forwards simulations were very similar, which is very good news indeed. A biologist not aware of the complexities of forwards, backwards simulations and the coalescent, might now naïvely ask why another simulation method is needed if existing methods perform just as well. To address this question the manuscript closes with a very neat example of what exactly is possible with forwards simulations that cannot be achieved using existing methods. The situation modeled is the growth and evolution of a set of 50 bacteria that are randomly distributed on a petri dish. One side of the petri dish is covered in an antibiotic the other is antibiotic-free. Over time, the bacteria grow and acquire antibiotic resistance mutations until the entire artificial petri dish is covered with a bacterial lawn. This simulation demonstrates that it is possible to simulate extremely complex (e.g. real world) scenarios to, for example, assess whether certain phenomena are expected with our current understanding of bacterial evolution, or whether there are additional forces that need to be taken into account. Hence, forwards simulators could significantly help us to understand what current models can and cannot explain in evolutionary biology.

References Cury J, Haller BC, Achaz G, Jay F (2021) Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM. bioRxiv, 2020.09.28.316869, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316869 De Maio N, Wilson DJ (2017) The Bacterial Sequential Markov Coalescent. Genetics, 206, 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.198796 Haller BC, Messer PW (2019) SLiM 3: Forward Genetic Simulations Beyond the Wright–Fisher Model. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy228 Hudson RR (2002) Generating samples under a Wright–Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics, 18, 337–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337 | Simulation of bacterial populations with SLiM | Jean Cury, Benjamin C. Haller, Guillaume Achaz, and Flora Jay | <p>Simulation of genomic data is a key tool in population genetics, yet, to date, there is no forward-in-time simulator of bacterial populations that is both computationally efficient and adaptable to a wide range of scenarios. Here we demonstrate... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frederic Bertels | 2020-10-02 19:03:42 | View | |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

18 Jan 2021

Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradientJ Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.17.952853Another step towards grasping the complexity of the environmental response of traitsRecommended by Benoit Pujol based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

One can only hope that one day, we will be able to evaluate how the ecological complexity surrounding natural populations affects their ability to adapt. This is more like a long term quest than a simple scientific aim. Many steps are heading in the right direction. This paper by Monroe and colleagues (2021) is one of them. References Gienapp P. & J.E. Brommer. 2014. Evolutionary dynamics in response to climate change. In: Charmentier A, Garant D, Kruuk LEB, editors. Quantitative genetics in the wild. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 254–273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199674237.003.0015 | Trait plasticity and covariance along a continuous soil moisture gradient | J Grey Monroe, Haoran Cai, David L Des Marais | <p>Water availability is perhaps the greatest environmental determinant of plant yield and fitness. However, our understanding of plant-water relations is limited because it is primarily informed by experiments considering soil moisture variabilit... |  | Phenotypic Plasticity | Benoit Pujol | 2020-02-20 16:34:40 | View | |

18 Mar 2025

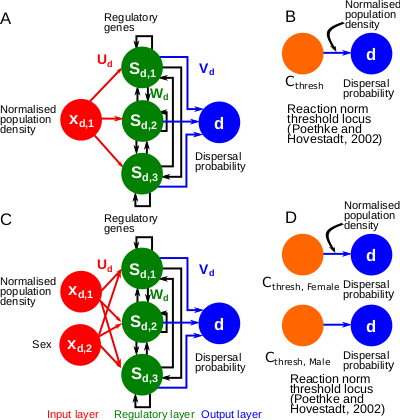

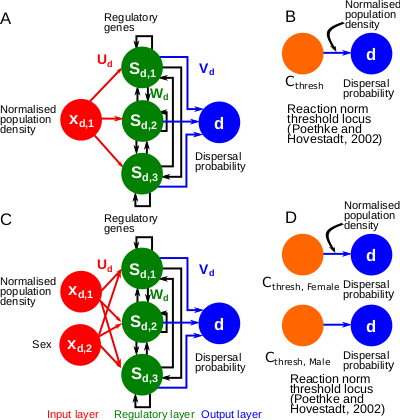

A gene-regulatory network model for density-dependent and sex-biased dispersal evolution during range expansionsJhelam N. Deshpande, Emanuel A. Fronhofer https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549508Evolved gene-regulatory networks underlying dispersal plasticity can accelerate range expansionsRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by Arnaud Le Rouzic and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Arnaud Le Rouzic and 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural populations rarely experience a uniform environment. Local density, resource availability, and mating opportunities often vary considerably across a population range. Theory has shown that such heterogeneity favours the evolution of density-dependent dispersal in the form of dispersal reaction norms. These models typically assume a simple genetic basis, with dispersal reaction norms encoded by a single Mendelian locus. Yet, dispersal plasticity is presumably controlled by more complex genetic architectures. Early work by Ezoe and Iwasa (1997) illustrated how evolved neural networks could generate dispersal reaction norms very similar to those predicted by Mendelian genetics.

In their manuscript, Deshpande and Fronhofer (2023) build on this work by examining how different genetic architectures influence the evolution of dispersal plasticity and its ecological consequences. They compare dispersal plasticity encoded either by a classical reaction norm controlled by a single Mendelian locus or by a gene-regulatory network following the Wagner model, where several interacting regulatory genes respond to local density cues and the individual's sex to determine dispersal probability.

Under stable conditions, both architectures successfully reproduce classical patterns of density- and sex-dependent dispersal. However, a clear difference emerges once populations expand into new, empty territories. Evolved gene-regulatory networks harbour substantially more cryptic genetic variation, which is revealed under these changing conditions. Previously hidden variation becomes exposed to selection at the expanding front, where low-density conditions create novel selective pressures. As a result, dispersal increases significantly, accelerating range expansions compared to the simpler, single-locus architectures.

These findings highlight how the genetic architecture of ecologically relevant traits, such as dispersal, not only shapes range dynamics but can also influence how populations respond to the demographic and environmental shifts encountered during expansion. By demonstrating that gene-regulatory networks facilitate faster range expansions due to their ability to store and later reveal cryptic genetic variation, Deshpande and Fronhofer take a useful step toward integrating genetic complexity into eco-evolutionary models.

References

Ezoe, H. and Iwasa, Y. (1997), Evolution of condition-dependent dispersal: A genetic-algorithm search for the ESS reaction norm. Popul Ecol, 39: 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02765258

Jhelam N. Deshpande, Emanuel A. Fronhofer (2023) A gene-regulatory network model for density-dependent and sex-biased dispersal evolution during range expansions. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol

| A gene-regulatory network model for density-dependent and sex-biased dispersal evolution during range expansions | Jhelam N. Deshpande, Emanuel A. Fronhofer | <p>Dispersal is key to understanding ecological and evolutionary dynamics. Dispersal may itself evolve and exhibit phenotypic plasticity. Specifically, organisms may modulate their dispersal rates in response to the density of their conspecifics (... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity | Charles Mullon | 2023-12-17 20:54:44 | View | |

05 Jun 2018

Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species poolsJoaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal https://doi.org/10.1101/149617Recent assembly of European biogeographic species poolRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBiodiversity is unevenly distributed over time, space and the tree of life [1]. The fact that regions are richer than others as exemplified by the latitudinal diversity gradient has fascinated biologists as early as the first explorers travelled around the world [2]. Provincialism was one of the first general features of land biotic distributions noted by famous nineteenth century biologists like the phytogeographers J.D. Hooker and A. de Candolle, and the zoogeographers P.L. Sclater and A.R. Wallace [3]. When these explorers travelled among different places, they were struck by the differences in their biotas (e.g. [4]). The limited distributions of distinctive endemic forms suggested a history of local origin and constrained dispersal. Much biogeographic research has been devoted to identifying areas where groups of organisms originated and began their initial diversification [3]. Complementary efforts found evidence of both historical barriers that blocked the exchange of organisms between adjacent regions and historical corridors that allowed dispersal between currently isolated regions. The result has been a division of the Earth into a hierarchy of regions reflecting patterns of faunal and floral similarities (e.g. regions, subregions, provinces). Therefore a first ensuing question is: “how regional species pools have been assembled through time and space?”, which can be followed by a second question: “what are the ecological and evolutionary processes leading to differences in species richness among species pools?”. To address these questions, the study of Calatayud et al. [5] developed and performed an interesting approach relying on phylogenetic data to identify regional and sub-regional pools of European beetles (using the iconic ground beetle genus Carabus). Specifically, they analysed the processes responsible for the assembly of species pools, by comparing the effects of dispersal barriers, niche similarities and phylogenetic history. They found that Europe could be divided in seven modules that group zoogeographically distinct regions with their associated faunas, and identified a transition zone matching the limit of the ice sheets at Last Glacial Maximum (19k years ago). Deviance of species co-occurrences across regions, across sub-regions and within each region was significantly explained, primarily by environmental niche similarity, and secondarily by spatial connectivity, except for northern regions. Interestingly, southern species pools are mostly separated by dispersal barriers, whereas northern species pools are mainly sorted by their environmental niches. Another important finding of Calatayud et al. [5] is that most phylogenetic structuration occurred during the Pleistocene, and they show how extreme recent historical events (Quaternary glaciations) can profoundly modify the composition and structure of geographic species pools, as opposed to studies showing the role of deep-time evolutionary processes. The study of biogeographic assembly of species pools using phylogenies has never been more exciting and promising than today. Catalayud et al. [5] brings a nice study on the importance of Pleistocene glaciations along with geographical barriers and niche-based processes in structuring the regional faunas of European beetles. The successful development of powerful analytical tools in recent years, in conjunction with the rapid and massive increase in the availability of biological data (including molecular phylogenies, fossils, georeferrenced occurrences and ecological traits), will allow us to disentangle complex evolutionary histories. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and methodological shortcomings, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and biotic triggers are intertwined on shaping the Earth’s stupendous biological diversity. I hope that the Catalayud et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) will help movement in that direction, and that it will provide interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions. Applied to a European beetle radiation, they were able to tease apart the relative contributions of biotic (niche-based processes) versus abiotic (geographic barriers and climate change) factors. References [1] Rosenzweig ML. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools | Joaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal | <p>Despite the description of bioregions dates back from the origin of biogeography, the processes originating their associated species pools have been seldom studied. Ancient historical events are thought to play a fundamental role in configuring... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2017-06-14 07:30:32 | View | |

26 Nov 2019

Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studiesJobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume https://doi.org/10.1101/656413Understanding the effects of linkage and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptationRecommended by Kathleen Lotterhos based on reviews by Pär Ingvarsson and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic correlations among traits are ubiquitous in nature. However, we still have a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of trait correlations. Some genetic correlations among traits arise because of pleiotropy - single mutations or genotypes that have effects on multiple traits. Other genetic correlations among traits arise because of linkage among mutations that have independent effects on different traits. Teasing apart the differential effects of pleiotropy and linkage on trait correlations is difficult, because they result in very similar genetic patterns. However, understanding these differential effects gives important insights into how ubiquitous pleiotropy may be in nature. References [1] Chebib, J. and Guillaume, F. (2019). Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies. bioRxiv, 656413, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/656413 | Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies | Jobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume | <p>Genetic correlations between traits may cause correlated responses to selection depending on the source of those genetic dependencies. Previous models described the conditions under which genetic correlations were expected to be maintained. Sel... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Kathleen Lotterhos | 2019-06-05 13:51:43 | View | |

21 Feb 2023

Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugsJonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778Nutritional symbioses in triatomines: who is playing?Recommended by Natacha Kremer based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and Olivier DuronNearly 8 million people are suffering from Chagas disease in the Americas. The etiological agent, Trypanosoma cruzi, is mainly transmitted by triatomine bugs, also known as kissing or vampire bugs, which suck blood and transmit the parasite through their feces. Among these triatomine species, Rhodnius prolixus is considered the main vector, and many studies have focused on characterizing its biology, physiology, ecology and evolution. Interestingly, given that Rhodnius species feed almost exclusively on blood, their diet is unbalanced, and the insects can lack nutrients and vitamins that they cannot synthetize themself, such as B-vitamins. In all insects feeding exclusively on blood, symbioses with microbes producing B-vitamins (mainly biotin, riboflavin and folate) have been widely described (see review in Duron and Gottlieb 2020) and are critical for insect development and reproduction. These co-evolved relationships between blood feeders and nutritional symbionts could now be considered to develop new control methods, by targeting the ‘Achille’s heel’ of the symbiotic association (i.e., transfer of nutrient and / or control of nutritional symbiont density). But for this, it is necessary to better characterize the relationships between triatomines and their symbionts. R. prolixus is known to be associated with several symbionts. The extracellular gut symbiont Rhodococcus rhodnii, which reaches high bacterial densities and is almost fixed in R. prolixus populations, appears to be a nutritional symbiont under many blood sources. This symbiont can provide B-vitamins such as biotin (B7), niacin (B3), thiamin (B1), pyridoxin (B6) or riboflavin (B2) and can play an important role in the development and the reproduction of R. prolixus (Pachebat et al. (2013) and see review in Salcedo-Porras et al. (2020)). This symbiont is orally acquired through egg smearing, ensuring the fidelity of transmission of the symbiont from mother to offspring. However, as recently highlighted by Tobias et al. (2020) and Gilliland et al. (2022), other gut microbes could also participate to the provision of B-vitamins, and R. rhodnii could additionally provide metabolites (other than B-vitamins) increasing bug fitness. In the study from Filée et al., the authors focused on Wolbachia, an intracellular, maternally inherited bacterium, known to be a nutritional symbiont in other blood-sucking insects such as bedbugs (Nikoh et al. 2014), and its potential role in vitamin provision in triatomine bugs. After screening 17 different triatomine species from the 3 phylogenetic groups prolixus, pallescens and pictipes, they first show that Wolbachia symbionts are widely distributed in the different Rhodnius species. Contrary to R. rhodnii that were detected in all samples, Wolbachia prevalence was patchy and rarely fixed. The authors then sequenced, assembled, and compared 13 Wolbachia genomes from the infected Rhodnius species. They showed that all Wolbachia are phylogenetically positioned in the supergroup F that contains wCle (the Wolbachia from bedbugs). In addition, 8 Wolbachia strains (out of 12) encode a biotin operon under strong purifying selection, suggesting the preservation of the biological function and the metabolic potential of Wolbachia to supplement biotin in their Rhodnius host. From the study of insect genomes, the authors also evidenced several horizontal transfers of genes from Wolbachia to Rhodnius genomes, which suggests a complex evolutionary interplay between vampire bugs and their intracellular symbiont. This nice piece of work thus provides valuable information to the fields of multiple partners / nutritional symbioses and Wolbachia research. Dual symbioses described in insects feeding on unbalanced diets generally highlight a certain complementarity between symbionts that ensure the whole nutritional complementation. The study presented by Filée et al. leads rather to consider the impact of multiple symbionts with different lifestyles and transmission modes in the provision of a specific nutritional benefit (here, biotin). Because of the low prevalence of Wolbachia in certain species, a “ménage à trois” scenario would rather be replaced by an “open couple”, where the host relationship with new symbiotic partners (more or less stable at the evolutionary timescale) could provide benefits in certain ecological situations. The results also support the potential for Wolbachia to evolve rapidly along a continuum between parasitism and mutualism, by acquiring operons encoding critical pathways of vitamin biosynthesis. References Duron O. and Gottlieb Y. (2020) Convergence of Nutritional Symbioses in Obligate Blood Feeders. Trends in Parasitology 36(10):816-825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.07.007 Filée J., Agésilas-Lequeux K., Lacquehay L., Bérenger J.-M., Dupont L., Mendonça V., Aristeu da Rosa J. and Harry M. (2023) Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs. bioRxiv, 2022.09.06.506778, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778 Gilliland C.A. et al. (2022) Using axenic and gnotobiotic insects to examine the role of different microbes on the development and reproduction of the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16800 Nikoh et al. (2014) Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. PNAS. 111(28):10257-10262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409284111 Pachebat, J.A. et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of Rhodococcus rhodnii strain LMG5362, a symbiont of Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae), the principle vector of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genome Announc. 1(3):e00329-13. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomea.00329-13 Salcedo-Porras N., et al. (2020). The role of bacterial symbionts in Triatomines: an evolutionary perspective. Microorganisms. 8:1438. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms8091438 Tobias N.J., Eberhard F.E., Guarneri A.A. (2020) Enzymatic biosynthesis of B-complex vitamins is supplied by diverse microbiota in the Rhodnius prolixus anterior midgut following Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 3395-3401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.031 | Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs | Jonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry | <p>The nutritional symbiosis promoted by bacteria is a key determinant for adaptation and evolution of many insect lineages. A complex form of nutritional mutualism that arose in blood-sucking insects critically depends on diverse bacterial symbio... |  | Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Natacha Kremer | Alejandro Manzano Marín | 2022-09-13 17:36:46 | View |

12 Nov 2021

How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy treeJordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.25.394544An ancient age of open-canopy landscapes in northern Madagascar? Evidence from the population genetic structure of a forest treeRecommended by Miguel de Navascués based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona

We currently live in the Anthropocene, the geological age characterized by a profound impact of human populations in the ecosystems and the environment. While there is little doubt about the action of humans in the shaping of present landscapes, it can be difficult to determine what the state of those landscapes was before humans started to modify them. This is the case of the Madagascar grasslands, whose origins have been debated with arguments proposing them either as anthropogenic, created with the arrival of humans around 2000BP, or as ancient features of the natural landscape with a forest fragmentation process due to environmental changes pre-dating human arrival [e.g. 1,2]. One way to clarify this question is through the genetic study of native species. Population continuity and fragmentation along time shape the structure of the genetic diversity in space. Species living in a uniform continuous habitat are expected to show genetic structuring determined only by geographical distance. Recent changes of the habitat can take many generations to reshape that genetic structure [3]. Thus, we expect genetic structure to reflect ancient features of the landscape. The work by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] studies the factors determining the population genetic structure of the Malagasy spiny olive (Noronhia spinifolia). This narrow endemic species is distributed in the discontinuous forest patches of the Loky-Manambato region (northern Madagascar). Jordi Salmona and collaborators genotyped 72 individuals distributed across the species distribution with restriction associated DNA sequencing and organelle microsatellite markers. Then, they studied the population genetic structure of the species. Using isolation-by-resistance models [5], they tested the influence of several landscape features (forest cover, roads, rivers, slope, etc.) on the connectivity between populations. Maternally inherited loci (chloroplast and mitochondria) and bi-parentally inherited loci (nuclear), were analysed separately in an attempt to identify the role of pollen and seed dispersal in the connectivity of populations. Despite the small distribution of the species, Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] found remarkable levels of genetic diversity. The spatial structure of this diversity was found to be mainly explained by the forest cover of the landscape, suggesting that the landscape has been composed by patches of forests and grasslands for a long time. The main role of forest cover for the connectivity among populations also highlights the importance of riparian forest as dispersal corridors. Finally, differences between organelle and nuclear markers were not enough to establish any strong conclusion about the differences between pollen and seed dispersal. The results presented by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] contribute to the understanding of the history and ecology of understudied Madagascar ecosystems. Previous population genetic studies in some forest-dwelling mammals have been interpreted as supporting an old age for the fragmented landscapes in northern Madagascar [e.g. 1,6]. To my knowledge, this is the first study on a tree species. While this work might not completely settle the debate, it emphasizes the importance of studying a diversity of species to understand the biogeographic dynamics of a region. References 1. Quéméré, E., X. Amelot, J. Pierson, B. Crouau-Roy, L. Chikhi (2012) Genetic data suggest a natural prehuman origin of open habitats in northern Madagascar and question the deforestation narrative in this region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of | How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy tree | Jordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard | <p>Understanding landscape changes is central to predicting evolutionary trajectories and defining conservation practices. While human-driven deforestation is intense throughout Madagascar, exception in areas like the Loky-Manambato region (North)... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Miguel de Navascués | 2020-11-27 09:07:21 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang