Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 May 2023

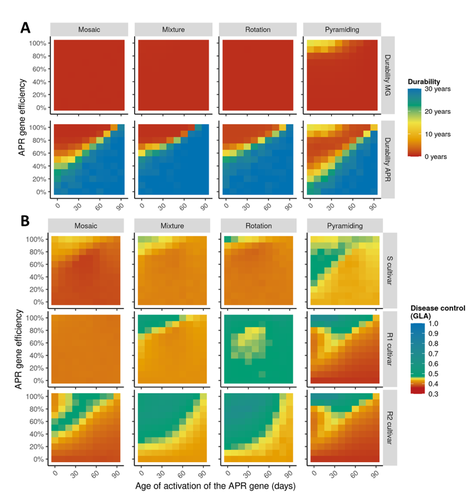

Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemmaLoup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787Plant resistance to pathogens: just you wait?Recommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by Jean-Paul Soularue and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this preprint, Rimbaud et al. (2023) examine whether Adult Plant Resistance (APR), where plants delay their response to pathogens, is a viable alternative when the solution to evolve complete resistance from the seedling stage exists. At first glance, delaying resistance seems like a counter-intuitive strategy, unless it can result in a weaker selection of the pathogen, and therefore slow down its adaption to plant resistance. The approach of Rimbaud et al. is to incorporate as much of the mechanisms as possible into a model. By accounting for explicit spatio-temporal dynamics, stochasticity, and the coupling between demography and population genetics, to simulate an agricultural landscape, they reach a nuanced conclusion. Weaker and delayed activation of genes that confer APR does indeed reduce the selection pressure acting on the pathogen, at the cost of overall less effective protection. The alternative strategy of rapid or complete activation of these genes, although it results in better results in defending against the pathogen, is at risk of being overcome because it introduces a stronger selection pressure. One important feature of this work is that it accounts for agricultural practices. The landscape that is simulated can account for monoculture, mosaic cultures, mixed cultures, and rotations of crops (with different strategies for resistance). This introduces an interesting element to the conclusion: that human practices will have an impact on the selection pressures acting within the system. Perhaps the most striking result is that, for the plants, it might be more beneficial to bear the cost of a wild-type pathogen that can benefit from delayed activation of resistance, and therefore exclude the more virulent strains by simply being there first, and essentially buying the plant some time before it activates its resistance more completely. When the landscape is aggregated, even wild-type pathogens can cause severe epidemics; increasing fragmentation, because it enables connectivity between patches of plants with different strategies, allows pathogens to move across cultivars, and reduces the epidemic risk on susceptible plants. These results should encourage scaling up the perspective on APR, and indeed Rimbaud et al. adopt a landscape-scale perspective, to show that APR genes and genes conferring more complete resistance early on can have synergistic effects. This is, again, both an interesting result for evolutionary biologists, but also a useful way to prioritize different crop management strategies over large spatial scales. References Rimbaud, Loup, et al. Durable Resistance or Efficient Disease Control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the Heart of the Dilemma. 2023. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.30.505787 | Durable resistance or efficient disease control? Adult Plant Resistance (APR) at the heart of the dilemma | Loup Rimbaud, Julien Papaïx, Jean-François Rey, Benoît Moury, Luke G. Barrett, Peter H. Thrall | <p style="text-align: justify;">Adult plant resistance (APR) is an incomplete and delayed protection of plants against pathogens. At first glance, such resistance should be less efficient than classical major-effect resistance genes, which confer ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Timothée Poisot | 2022-09-02 16:36:32 | View | |

28 Sep 2020

Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantageLudovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens https://doi.org/10.1101/616409Evolutionary insights into disassortative mating and its association to an ecologically relevant supergeneRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers

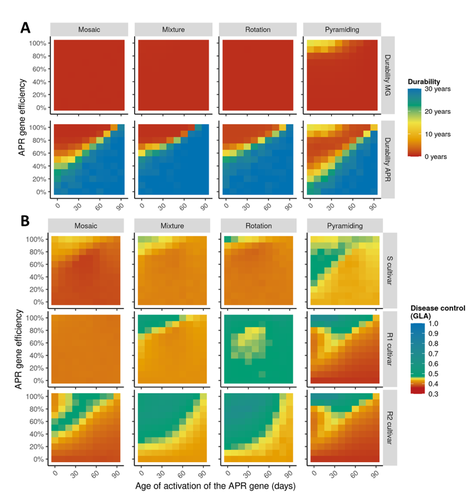

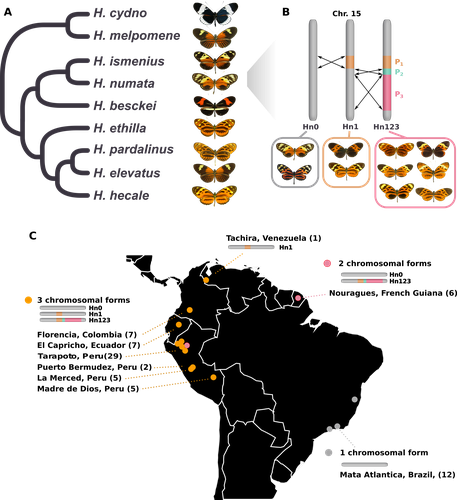

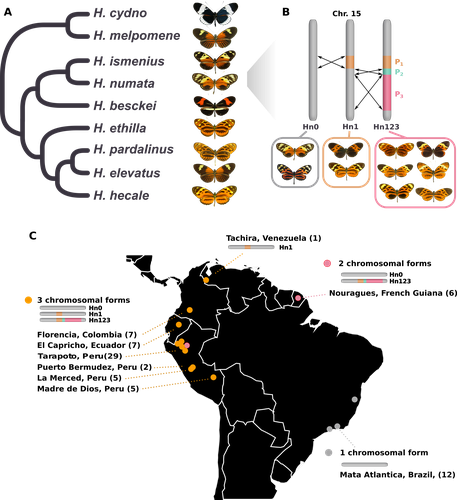

Heliconius butterflies are famous for their colorful wing patterns acting as a warning of their chemical defenses [1]. Most species are involved in Müllerian mimicry assemblies, as predators learn to associate common wing patterns with unpalatability and preferentially target rare variants. Such positive-frequency dependent selection homogenizes wing patterns at different localities, and in several species, all individuals within a community belong to the same morph [2]. In this respect, H. numata stands out. This species shows stable local polymorphism across multiple localities, with local populations home to up to seven distinct morphs [2]. Although a balance between migration and local positive-frequency dependent selection can allow some degree of local polymorphism, theory suggests that this occurs only when migration is within a narrow window [3]. References [1] Merrill, R M, K K Dasmahapatra, J W Davey, D D Dell'Aglio, J J Hanly, B Huber, C D Jiggins, et al. (2015). The Diversification of Heliconius butterflies: What Have We Learned in 150 Years? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28 (8), 1417–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12672. | Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantage | Ludovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens | <p>The evolution of mate preferences may depend on natural selection acting on the mating cues and on the underlying genetic architecture. While the evolution of assortative mating with respect to locally adapted traits has been well-characterized... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Mullon | 2019-10-29 09:55:18 | View | |

30 Mar 2023

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterflyMaría Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, Mathieu Joron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea. The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale. Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding. REFERENCES Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348 | Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly | María Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Selection shapes genetic diversity around target mutations, yet little is known about how selection on specific loci affects the genetic trajectories of populations, including their genomewide patterns of diversity ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Chris Jiggins | 2021-10-13 17:54:33 | View | |

23 Feb 2024

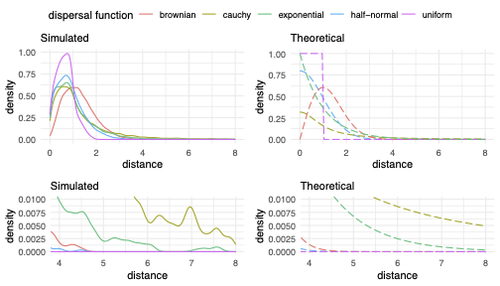

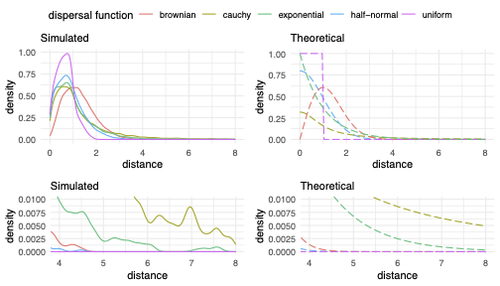

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

14 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiMarianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055A valuable work lying at the crossroad of neuro-ethology, evolution and ecology in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiRecommended by Arnaud Estoup and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerAdaptations to a new ecological niche allow species to access new resources and circumvent competitors and are hence obvious pathways of evolutionary success. The evolution of agricultural pest species represents an important case to study how a species adapts, on various timescales, to a novel ecological niche. Among the numerous insects that are agricultural pests, the ability to lay eggs (or oviposit) in ripe fruit appears to be a recurrent scenario. Fruit flies (family Tephritidae) employ this strategy, and include amongst their members some of the most destructive pests (e.g., the olive fruit fly Bactrocera olea or the medfly Ceratitis capitata). In their ms, Karageorgi et al. [1] studied how Drosophila suzukii, a new major agricultural pest species that recently invaded Europe and North America, evolved the novel behavior of laying eggs into undamaged fresh fruit. The close relatives of D. suzukii lay their eggs on decaying plant substrates, and thus this represents a marked change in host use that links to substantial economic losses to the fruit industry. Although a handful of studies have identified genetic changes causing new behaviors in various species, the question of the evolution of behavior remains a largely uncharted territory. The study by Karageorgi et al. [1] represents an original and most welcome contribution in this domain for a non-model species. Using clever behavioral experiments to compare D. suzukii to several related Drosophila species, and complementing those results with neurogenetics and mutant analyses using D. suzukii, the authors nicely dissect the sensory changes at the origin of the new egg-laying behavior. The experiments they describe are easy to follow, richly illustrate through figures and images, and particularly well designed to progressively decipher the sensory bases driving oviposition of D. suzukii on ripe fruit. Altogether, Karageorgi et al.’s [1] results show that the egg-laying substrate preference of D. suzukii has considerably evolved in concert with its morphology (especially its enlarged, serrated ovipositor that enables females to pierce the skin of many ripe fruits). Their observations clearly support the view that the evolution of traits that make D. suzukii an agricultural pest included the modification of several sensory systems (i.e. mechanosensation, gustation and olfaction). These differences between D. suzukii and its close relatives collectively underlie a radical change in oviposition behavior, and were presumably instrumental in the expansion of the ecological niche of the species. The authors tentatively propose a multi-step evolutionary scenario from their results with the emergence of D. suzukii as a pest species as final outcome. Such formalization represents an interesting evolutionary model-framework that obviously would rely upon further data and experiments to confirm and refine some of the evolutionary steps proposed, especially the final and recent transition of D. suzukii from non-invasive to invasive species. References [1] Karageorgi M, Bräcker LB, Lebreton S, Minervino C, Cavey M, Siju KP, Grunwald Kadow IC, Gompel N, Prud’homme B. 2017. Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii. Current Biology, 27: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055 | Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii | Marianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme | The rise of a pest species represents a unique opportunity to address how species evolve new behaviors and adapt to novel ecological niches. We address this question by studying the egg-laying behavior of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive agricultur... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution | Arnaud Estoup | 2017-03-13 17:42:00 | View | |

28 Feb 2018

Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid waspMarie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant https://doi.org/10.1101/169268Incestuous insects in nature despite occasional fitness costsRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Bertanne Visser based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersInbreeding, or mating between relatives, generally lowers fitness [1]. Mating between genetically similar individuals can result in higher levels of homozygosity and consequently a higher frequency with which recessive disease alleles may be expressed within a population. Reduced fitness as a consequence of inbreeding, or inbreeding depression, can vary between individuals, sexes, populations and species [2], but remains a pervasive challenge for many organisms with small local population sizes, including humans [3]. But all is not lost for individuals within small populations, because an array of mechanisms can be employed to evade the negative effects of inbreeding [4], including sib-mating avoidance and dispersal [5, 6]. Despite thorough investigation of inbreeding and sib-mating avoidance in the laboratory, only very few studies have ventured into the field besides studies on vertebrates and eusocial insects. The study of Collet et al. [7] is a surprising exception, where the effect of male density and frequency of relatives on inbreeding avoidance was tested in the laboratory, after which robust field collections and microsatellite genotyping were used to infer relatedness and dispersal in natural populations. The parasitic wasp Venturia canescens is an excellent model system to study inbreeding, because mating success was previously found to decrease with increasing relatedness between mates in the laboratory [8] and this species thus suffers from inbreeding depression [9–11]. The authors used an elegant design combining population genetics and model simulations to estimate relatedness of mating partners in the field and compared that with a theoretical distribution of potential mate encounters when random mating is assumed. One of the most important findings of this study is that mating between siblings is not avoided in this species in the wild, despite negative fitness effects when inbreeding does occur. Similar findings were obtained for another insect species, the field cricket Gryllus campestris [12], which leaves us to wonder whether inbreeding tolerance could be more common in nature than currently appreciated. The authors further looked into sex-specific dispersal patterns between two patches located a few hundred meters apart. Females were indeed shown to be more related within a patch, but no genetic differences were observed between males, suggesting that V. canescens males more readily disperse. Moreover, microsatellite data at 18 different loci did not reveal genetic differentiation between populations approximately 300 kilometers apart. Gene flow is thus occurring over considerable distances, which could play an important role in the ability of this species to avoid negative fitness consequences of inbreeding in nature. Another interesting aspect of this work is that discrepancies were found between laboratory- and field-based data. What is the relevance of laboratory-based experiments if they cannot predict what is happening in the wild? Many, if not most, biologists (including us) bring our model system into the laboratory to control, at least to some extent, the plethora of environmental factors that could potentially affect our system (in ways that we do not want). Most behavioral studies on mating patterns and sexual selection are conducted in standardized laboratory conditions, but sexual selection is in essence social selection, because an individual’s fitness is partly determined by the phenotype of its social partners (i.e. the social environment) [13]. The social environment may actually dictate the expression of female mate choice and it is unclear how potential laboratory-induced social biases affect mating outcome. In V. canescens, findings using field-caught individuals paint a completely opposite picture of what was previously shown in the laboratory, i.e. sib-avoidance is not taking place in the field. It is likely that density, level of relatedness, sex ratio in the field, and/or the size of experimental arenas in the lab are all factors affecting mate selectivity, as we have previously shown in a butterfly [14–16]. If females, for example, typically only encounter a few males in sequence in the wild, it may be problematic for them to express choosiness when confronted simultaneously with two or more males in the laboratory. A recent study showed that, in the wild, female moths take advantage of staying in groups to blur male choosiness [17]. It is becoming more and more clear that what we observe in the laboratory may not actually reflect what is happening in nature [18]. Instead of ignoring the species-specific life history and ecological features of our favorite species when conducting lab experiments, we suggest that it is time to accept that we now have the theoretical foundations to tease apart what in this “environmental noise” actually shapes sexual selection in nature. Explicitly including ecology in studies on sexual selection will allow us to make more meaningful conclusions, i.e. rather than “this is what may happen in the wild”, we would be able to state “this is what often happens in nature”. References [1] Charlesworth D & Willis JH. 2009. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664 | Insects and incest: sib-mating tolerance in natural populations of a parasitoid wasp | Marie Collet, Isabelle Amat, Sandrine Sauzet, Alexandra Auguste, Xavier Fauvergue, Laurence Mouton, Emmanuel Desouhant | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (http://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100047) 1. Sib-mating avoidance is a pervasive behaviour that likely evolves in species subject to inbreeding dep... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-07-28 09:23:20 | View | |

20 Jan 2020

A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random ForestMarie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup https://doi.org/10.1101/671867Estimating recent divergence history: making the most of microsatellite data and Approximate Bayesian Computation approachesRecommended by Takeshi Kawakami and Concetta Burgarella based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield and 2 anonymous reviewersThe present-day distribution of extant species is the result of the interplay between their past population demography (e.g., expansion, contraction, isolation, and migration) and adaptation to the environment. Shedding light on the timing and magnitude of key demographic events helps identify potential drivers of such events and interaction of those drivers, such as life history traits and past episodes of environmental shifts. The understanding of the key factors driving species evolution gives important insights into how the species may respond to changing conditions, which can be particularly relevant for the management of harmful species, such as agricultural pests (e.g. [1]). Meaningful demographic inferences present major challenges. These include formulating evolutionary scenarios fitting species biology and the eco-geographical context and choosing informative molecular markers and accurate quantitative approaches to statistically compare multiple demographic scenarios and estimate the parameters of interest. A further issue comes with result interpretation. Accurately dating the inferred events is far from straightforward since reliable calibration points are necessary to translate the molecular estimates of the evolutionary time into absolute time units (i.e. years). This can be attempted in different ways, such as by using fossil and archaeological records, heterochronous samples (e.g. ancient DNA), and/or mutation rate estimated from independent data (e.g. [2], [3] for review). Nonetheless, most experimental systems rarely meet these conditions, hindering the comprehensive interpretation of results. The contribution of Chapuis et al. [4] addresses these issues to investigate the recent history of the African insect pest Schistocerca gregaria (desert locust). They apply Approximate Bayesian Computation-Random Forest (ABC-RF) approaches to microsatellite markers. Owing to their fast mutation rate microsatellite markers offer at least two advantages: i) suitability for analyzing recently diverged populations, and ii) direct estimate of the germline mutation rate in pedigree samples. The work of Chapuis et al. [4] benefits of both these advantages, since they have estimates of mutation rate and allele size constraints derived from germline mutations in the species [5]. The main aim of the study is to infer the history of divergence of the two subspecies of the desert locust, which have spatially disjoint distribution corresponding to the dry regions of North and West-South Africa. They first use paleo-vegetation maps to formulate hypotheses about changes in species range since the last glacial maximum. Based on them, they generate 12 divergence models. For the selection of the demographic model and parameter estimation, they apply the recently developed ABC-RF approach, a powerful inferential tool that allows optimizing the use of summary statistics information content, among other advantages [6]. Some methodological novelties are also introduced in this work, such as the computation of the error associated with the posterior parameter estimates under the best scenario. The accuracy of timing estimate is assured in two ways: i) by the use of microsatellite markers with known evolutionary dynamics, as underlined above, and ii) by assessing the divergence time threshold above which posterior estimates are likely to be biased by size homoplasy and limits in allele size range [7]. The best-supported model suggests a recent divergence event of the subspecies of S. gregaria (around 2.6 kya) and a reduction of populations size in one of the subspecies (S. g. flaviventris) that colonized the southern distribution area. As such, results did not support the hypothesis that the southward colonization was driven by the expansion of African dry environments associated with the last glacial maximum, as it has been postulated for other arid-adapted species with similar African disjoint distributions [8]. The estimated time of divergence points at a much more recent origin for the two subspecies, during the late Holocene, in a period corresponding to fairly stable arid conditions similar to current ones [9,10]. Although the authors cannot exclude that their microsatellite data bear limited information on older colonization events than the last one, they bring arguments in favour of alternative explanations. The hypothesis privileged does not involve climatic drivers, but the particularly efficient dispersal behaviour of the species, whose individuals are able to fly over long distances (up to thousands of kilometers) under favourable windy conditions. A single long-distance dispersal event by a few individuals would explain the genetic signature of the bottleneck. There is a growing number of studies in phylogeography in arid regions in the Southern hemisphere, but the impact of past climate changes on the species distribution in this region remains understudied relative to the Northern hemisphere [11,12]. The study presented by Chapuis et al. [4] offers several important insights into demographic changes and the evolutionary history of an agriculturally important pest species in Africa, which could also mirror the history of other organisms in the continent. As the authors point out, there are necessarily some uncertainties associated with the models of past ecosystems and climate, especially for Africa. Interestingly, the authors argue that the information on paleo-vegetation turnover was more informative than climatic niche modeling for the purpose of their study since it made them consider a wider range of bio-geographical changes and in turn a wider range of evolutionary scenarios (see discussion in Supplementary Material). Microsatellite markers have been offering a useful tool in population genetics and phylogeography for decades, but their popularity is perhaps being taken over by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (the peak year of the number of the publication with “microsatellite” is in 2012 according to PubMed). This study reaffirms the usefulness of these classic molecular markers to estimate past demographic events, especially when species- and locus-specific microsatellite mutation features are available and a powerful inferential approach is adopted. Nonetheless, there are still hurdles to overcome, such as the limitations in scenario choice associated with the simulation software used (e.g. not allowing for continuous gene flow in this particular case), which calls for further improvement of simulation tools allowing for more flexible modeling of demographic events and mutation patterns. In sum, this work not only contributes to our understanding of the makeup of the African biodiversity but also offers a useful statistical framework, which can be applied to a wide array of species and molecular markers (microsatellites, SNPs, and WGS). References [1] Lehmann, P. et al. (2018). Complex responses of global insect pests to climate change. bioRxiv, 425488. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/425488 [2] Donoghue, P. C., & Benton, M. J. (2007). Rocks and clocks: calibrating the Tree of Life using fossils and molecules. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(8), 424-431. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.05.005 [3] Ho, S. Y., Lanfear, R., Bromham, L., Phillips, M. J., Soubrier, J., Rodrigo, A. G., & Cooper, A. (2011). Time‐dependent rates of molecular evolution. Molecular ecology, 20(15), 3087-3101. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05178.x [4] Chapuis, M.-P., Raynal, L., Plantamp, C., Meynard, C. N., Blondin, L., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020). A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest. bioRxiv, 671867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/671867 5] Chapuis, M.-P., Plantamp, C., Streiff, R., Blondin, L., & Piou, C. (2015). Microsatellite evolutionary rate and pattern in Schistocerca gregaria inferred from direct observation of germline mutations. Molecular ecology, 24(24), 6107-6119. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mec.13465 [6] Raynal, L., Marin, J. M., Pudlo, P., Ribatet, M., Robert, C. P., & Estoup, A. (2018). ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35(10), 1720-1728. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 [7] Estoup, A., Jarne, P., & Cornuet, J. M. (2002). Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Molecular ecology, 11(9), 1591-1604. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01576.x [8] Moodley, Y. et al. (2018). Contrasting evolutionary history, anthropogenic declines and genetic contact in the northern and southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1890), 20181567. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1567 [9] Kröpelin, S. et al. (2008). Climate-driven ecosystem succession in the Sahara: the past 6000 years. science, 320(5877), 765-768. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1154913 [10] Maley, J. et al. (2018). Late Holocene forest contraction and fragmentation in central Africa. Quaternary Research, 89(1), 43-59. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.97 [11] Beheregaray, L. B. (2008). Twenty years of phylogeography: the state of the field and the challenges for the Southern Hemisphere. Molecular Ecology, 17(17), 3754-3774. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03857.x [12] Dubey, S., & Shine, R. (2012). Are reptile and amphibian species younger in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere?. Journal of evolutionary biology, 25(1), 220-226. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02417.x ***** A video about this preprint is available here: | A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest | Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup | <p>Dating population divergence within species from molecular data and relating such dating to climatic and biogeographic changes is not trivial. Yet it can help formulating evolutionary hypotheses regarding local adaptation and future responses t... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Takeshi Kawakami | 2019-06-20 10:31:15 | View | |

25 Jun 2020

Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emmanuelle d'Alencon, Nicolas Nègre https://doi.org/10.1101/263186Speciation through selection on mitochondrial genes?Recommended by Astrid Groot based on reviews by Heiko Vogel and Sabine HaennigerWhether speciation through ecological specialization occurs has been a thriving research area ever since Mayr (1942) stated this to play a central role. In herbivorous insects, ecological specialization is most likely to happen through host plant differentiation (Funk et al. 2002). Therefore, after Dorothy Pashley had identified two host strains in the Fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, in 1988 (Pashley 1988), researchers have been trying to decipher the evolutionary history of these strains, as this seems to be a model species in which speciation is currently occurring through host plant specialization. Even though FAW is a generalist, feeding on many different host plant species (Pogue 2002) and a devastating pest in many crops, Pashley identified a so-called corn strain and a so-called rice strain in Puerto Rico. Genetically, these strains were found to differ mostly in an esterase, although later studies showed additional genetic differences and markers, mostly in the mitochondrial COI and the nuclear TPI. Recent genomic studies showed that the two strains are overall so genetically different (2% of their genome being different) that these two strains could better be called different species (Kergoat et al. 2012). So far, the most consistent differences between the strains have been their timing of mating activities at night (Schoefl et al. 2009, 2011; Haenniger et al. 2019) and hybrid incompatibilities (Dumas et al. 2015; Kost et al. 2016). Whether and to what extent host plant preference or performance contributed to the differentiation of these sympatrically occurring strains has remained unclear. References [1] Dumas, P. et al. (2015). Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host-plant variants: two host strains or two distinct species?. Genetica, 143(3), 305-316. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9829-2 | Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) | Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emm... | <p>Spodoptera frugiperda, the fall armyworm (FAW), is an important agricultural pest in the Americas and an emerging pest in sub-Saharan Africa, India, East-Asia and Australia, causing damage to major crops such as corn, sorghum and soybean. While... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Life History, Speciation | Astrid Groot | 2018-05-09 13:04:34 | View | |

28 Aug 2019

Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animalsMarjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/643619To tinker, evolution needs a supply of spare partsRecommended by Georgii Bazykin based on reviews by Konstantin Popadin, David Enard and 1 anonymous reviewerIs evolution adaptive? Not if there is no variation for natural selection to work with. Theory predicts that how fast a population can adapt to a new environment can be limited by the supply of new mutations coming into it. This supply, in turn, depends on two things: how often mutations occur and in how many individuals. If there are few mutations, or few individuals in whom they can originate, individuals will be mostly identical in their DNA, and natural selection will be impotent. References [1] G, J. A., Visser, M. de, Zeyl, C. W., Gerrish, P. J., Blanchard, J. L., and Lenski, R. E. (1999). Diminishing Returns from Mutation Supply Rate in Asexual Populations. Science, 283(5400), 404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.404 | Is adaptation limited by mutation? A timescale-dependent effect of genetic diversity on the adaptive substitution rate in animals | Marjolaine Rousselle, Paul Simion, Marie-Ka Tilak, Emeric Figuet, Benoit Nabholz, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Whether adaptation is limited by the beneficial mutation supply is a long-standing question of evolutionary genetics, which is more generally related to the determination of the adaptive substitution rate and its relationship with the effective... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Georgii Bazykin | 2019-05-21 09:49:16 | View | |

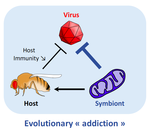

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbiontsMartinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778Hooked on WolbachiaRecommended by Ana Rivero and Natacha KremerThis very nice paper by Martinez et al. [1] provides further evidence, if further evidence was needed, of the extent to which heritable microorganisms run the evolutionary show. Reference [1] Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM. 2016. Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 283:20160778. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778 | Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts | Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM | Heritable symbionts that protect their hosts from pathogens have been described in a wide range of insect species. By reducing the incidence or severity of infection, these symbionts have the potential to reduce the strength of selection on genes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Ana Rivero | 2016-12-13 20:08:37 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer