Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

30 May 2023

slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapesMartin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041A new powerful tool to easily encode the geo-spatial dimension in population genetics simulationsRecommended by Emiliano Trucchi based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers

Models explaining the evolutionary processes operating in living beings are often impossible to test in the real world. This is mainly because of the long time (i.e., the number of generations) which is necessary for evolution to unfold. In addition, any such experiment would require a large number of individuals and, more importantly, many replicates to account for the inherent variance of the evolutionary processes under investigation. Only organisms with fast generation times and favourable rearing conditions can be used to explicitly test for specific evolutionary hypotheses. Computer simulations have filled this gap, revolutionising experimental testing in evolutionary biology by integrating genetic models into complex population dynamics, which can be run for (potentially) any length of time. Without going into an extensive description of the many available approaches for population genetics simulations (an exhaustive review can be found in Hoban et al 2012), three main aspects are, in my opinion, important for categorising and choosing one simulation approach over another. The first concerns the basic distinction between coalescent-based and individual-based simulators: the former being an efficient approach, which simulates back in time the coalescence events of a sample of homologous DNA fragments, while the latter is a more computationally intensive approach where all of the individuals (and their underlying genetic/genomic features) in the population are simulated forward-in-time, generation after generation. The second aspect concerns the simulation of natural selection. Although natural selection can be integrated into backward-in-time simulations, it is more realistically implemented as individual-based fitness in forward-in-time simulators. The third point, which has been often overlooked in evolutionary simulations, is about the possibility to design a simulation scenario where individuals and populations can exploit a physical (geographical) space. Amongst the coalescent-based simulators, SPLATCHE (Currat et al 2004), and its derivatives, is one of the few simulation tools deploying the coalescence process in sub-demes which are all connected by migration, thus getting as close as possible to a spatially-explicit population. On the other hand, individual-based simulators, whose development followed the increasing power of computational machines, offer a great opportunity to include spatio-temporal dynamics within a genomic simulation model. One of the most realistic and efficient individual-based forward-in-time simulators available is SLiM (Haller and Messer 2017), which allows users to implement simulations in arbitrarily complex spaces. Here, the more challenging part is encoding the spatially-explicit scenarios using the SLiM-specific EIDOS language. The new R package slendr (Petr et al 2022) offers a practical solution to this issue. By wrapping different tools into a well-known scripting language, slendr allows the design of spatiotemporal simulation scenarios which can be directly executed in the individual-based SLiM simulator, and the output stored with modern tree-sequence analysis tools (tskit; Kellerer et al 2018). Alternatively, simulations of non-spatial models can be run using a coalescent-based algorithm (msprime; Baumdicker et al 2022). The main advantage of slendr is that the whole simulative experiment can be performed entirely in the R environment, taking advantage of the many libraries available for geospatial and genomic data analysis, statistics, and visualisation. The open-source nature of this package, whose main aim is to make complex population genomics modelling more accessible, and the vibrant community of SLiM and tskit users will very likely make slendr widely used amongst the molecular ecology and evolutionary biology communities. Slendr handles real Earth cartographic data where users can design realistic demographic processes which characterise natural populations (i.e., expansions, displacement of large populations, interactions among populations, migrations, population splits, etc.) by changing spatial population boundaries across time and space. All in all, slendr is a very flexible and scalable framework to test the accuracy of spatial models, hypotheses about demography and selection, and interactions between organisms across space and time. REFERENCES Baumdicker, F., Bisschop, G., Goldstein, D., Gower, G., Ragsdale, A. P., Tsambos, G., ... & Kelleher, J. (2022). Efficient ancestry and mutation simulation with msprime 1.0. Genetics, 220(3), iyab229. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab229 Currat, M., Ray, N., & Excoffier, L. (2004). SPLATCHE: a program to simulate genetic diversity taking into account environmental heterogeneity. Molecular Ecology Notes, 4(1), 139-142. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00582.x Haller, B. C., & Messer, P. W. (2017). SLiM 2: flexible, interactive forward genetic simulations. Molecular biology and evolution, 34(1), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw211 Hoban, S., Bertorelle, G., & Gaggiotti, O. E. (2012). Computer simulations: tools for population and evolutionary genetics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(2), 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3130 Kelleher, J., Thornton, K. R., Ashander, J., & Ralph, P. L. (2018). Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS computational biology, 14(11), e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Petr, M., Haller, B. C., Ralph, P. L., & Racimo, F. (2023). slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2022.03.20.485041, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041 | slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes | Martin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo | <p style="text-align: justify;">One of the goals of population genetics is to understand how evolutionary forces shape patterns of genetic variation over time. However, because populations evolve across both time and space, most evolutionary proce... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emiliano Trucchi | 2022-09-14 12:57:56 | View | |

02 Nov 2022

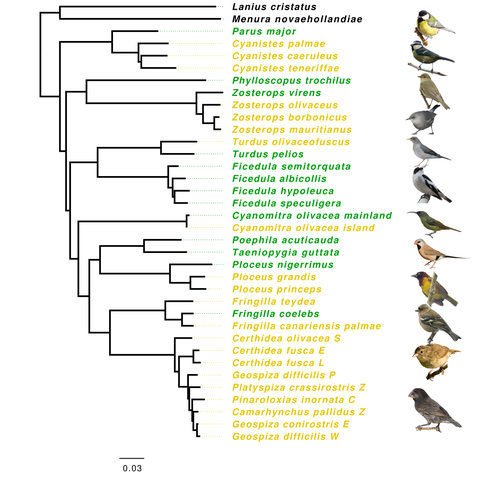

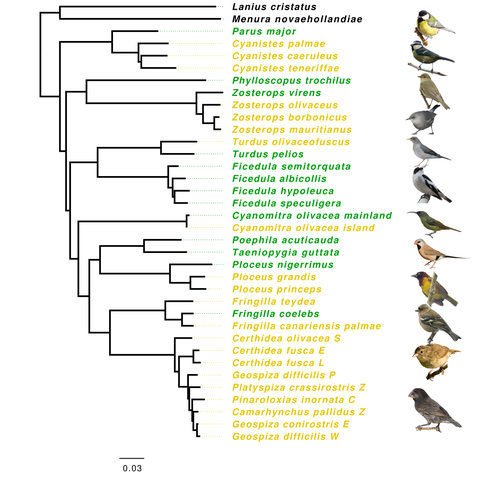

Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndromeMathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450Demographic effects may affect adaptation to islandsRecommended by Emma Berdan based on reviews by Steven Fiddaman and 3 anonymous reviewersThe unique challenges associated with living on an island often result in organisms displaying a specific suite of traits commonly referred to as “island syndrome” (Adler and Levins, 1994; Burns, 2019; Baeckens and Van Damme, 2020). Large phenotypic shifts such as changes in size (e.g. shifts to gigantism or dwarfism, Lomolino, 2005) or coloration (Doutrelant et al., 2016) abound in the literature. However, less obvious phenotypes may also play a key role in adaptation to islands. One such trait, reduced immune function, has important implications for the future of island populations in the face of anthropogenic-induced changes. Due to lower parasite pressure caused by a less diverse and less virulent parasite population, island hosts may show a decrease in immune defenses (Beadell et al., 2006; Pérez‐Rodríguez et al., 2013). However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as many studies have found ambiguous or conflicting results (Matson, 2006; Illera et al., 2015). While most previous work has examined various immunological parameters (e.g., antibody concentrations), here, Barthe et al. (2022) take the novel approach of examining molecular signatures of immune genes. Using comparative genomic data from 34 different species of birds the authors examine the ratio of synonymous substitutions (i.e., not changing an amino acid) to non-synonymous substitutions (i.e., changing an amino acid) in innate and acquired immune genes (Pn/Ps ratio). Because population sizes on islands are lower which will affect molecular evolution, they compare these results to data from 97 control genes. Assuming relaxed selection on islands predicts that the difference between the Pn/Ps ratio of immune genes and of control genes (ΔPn/Ps) is greater in island species compared to mainland ones. As with previous work the authors found that the results differ depending on the category of immune genes. Both forms of innate defense: beta-defensins and Toll-like receptors did not show higher ΔPn/Ps for island populations. As these genes still have a higher Pn/Ps than control genes, the authors argue these results are in line with these genes being under purifying selection but lacking an “island effect”. Instead, the authors argue that demographic effects (i.e., reductions in Ne) may lead to the decreased immunity documented in other studies. In contrast, there was a reduction in Pn/Ps in MHC II genes, known to be under balancing selection. This reduction was stronger in island species and thus the authors argue that this is the only class of genes where a role for relaxed selection can be invoked. Together these results demonstrate that the changes in immunity experienced by island species are complex and that different categories of immune genes can experience different selective pressures. By including control genes in their study, they particularly highlight the importance of accounting for shifts in Ne when examining patterns of island species evolution. Hopefully, this kind of framework will be applied to other taxa to determine if these results are widespread or more specific to birds. References Adler GH, Levins R (1994) The Island Syndrome in Rodent Populations. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1086/418744 Baeckens S, Van Damme R (2020) The island syndrome. Current Biology, 30, R338–R339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029 Barthe M, Doutrelant C, Covas R, Melo M, Illera JC, Tilak M-K, Colombier C, Leroy T, Loiseau C, Nabholz B (2022) Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome. bioRxiv, 2021.11.21.469450, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450 Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Graves GR, Jhala YV, Peirce MA, Rahmani AR, Fonseca DM, Fleischer RC (2006) Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2935–2944. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3671 Burns KC (2019) Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379953 Doutrelant C, Paquet M, Renoult JP, Grégoire A, Crochet P-A, Covas R (2016) Worldwide patterns of bird colouration on islands. Ecology Letters, 19, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12588 Illera JC, Fernández-Álvarez Á, Hernández-Flores CN, Foronda P (2015) Unforeseen biogeographical patterns in a multiple parasite system in Macaronesia. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1858–1870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12548 Lomolino MV (2005) Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01314.x Matson KD (2006) Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 Pérez-Rodríguez A, Ramírez Á, Richardson DS, Pérez-Tris J (2013) Evolution of parasite island syndromes without long-term host population isolation: parasite dynamics in Macaronesian blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 22, 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12084 | Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome | Mathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Shared ecological conditions encountered by species that colonize islands often lead to the evolution of convergent phenotypes, commonly referred to as “island syndrome”. Reduced immune functions have been previousl... |  | Adaptation, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emma Berdan | 2021-11-28 11:01:31 | View | |

03 May 2020

When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue?Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl https://doi.org/10.1101/622142Reconciling the upsides and downsides of migration for evolutionary rescueRecommended by Claudia Bank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolutionary response of populations to changing or novel environments is a topic that unites the interests of evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and biomedical researchers [1]. A prominent phenomenon in this research area is evolutionary rescue, whereby a population that is otherwise doomed to extinction survives due to the spread of new or pre-existing mutations that are beneficial in the new environment. Scenarios of evolutionary rescue require a specific set of parameters: the absolute growth rate has to be negative before the rescue mechanism spreads, upon which the growth rate becomes positive. However, potential examples of its relevance exist (e.g., [2]). From a theoretical point of view, the technical challenge but also the beauty of evolutionary rescue models is that they combine the study of population dynamics (i.e., changes in the size of populations) and population genetics (i.e., changes in the frequencies in the population). Together, the potential relevance of evolutionary rescue in nature and the models' theoretical appeal has resulted in a suite of modeling studies on the subject in recent years. References [1] Bell, G. (2017). Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48(1), 605-627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue? | Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl | <p>Experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the impact of gene flow on the probability of evolutionary rescue in structured habitats. Mathematical modelling and simulations of evolutionary rescue in spatially or otherwise structured p... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Claudia Bank | 2019-05-22 11:12:13 | View | |

03 Jun 2019

Transcriptomic response to divergent selection for flowering time in maize reveals convergence and key players of the underlying gene regulatory networkMaud Irène Tenaillon, Khawla Sedikki, Maeva Mollion, Martine Le Guilloux, Elodie Marchadier, Adrienne Ressayre, Christine Dillmann https://doi.org/10.1101/461947Early and late flowering gene expression patterns in maizeRecommended by Tanja Pyhäjärvi based on reviews by Laura Shannon and 2 anonymous reviewersArtificial selection experiments are key experiments in evolutionary biology. The demonstration that application of selective pressure across multiple generations results in heritable phenotypic changes is a tangible and reproducible proof of the evolution by natural selection. References [1] Hill, W. G., & Caballero, A. (1992). Artificial selection experiments. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 23(1), 287-310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.23.110192.001443 | Transcriptomic response to divergent selection for flowering time in maize reveals convergence and key players of the underlying gene regulatory network | Maud Irène Tenaillon, Khawla Sedikki, Maeva Mollion, Martine Le Guilloux, Elodie Marchadier, Adrienne Ressayre, Christine Dillmann | <p>Artificial selection experiments are designed to investigate phenotypic evolution of complex traits and its genetic basis. Here we focused on flowering time, a trait of key importance for plant adaptation and life-cycle shifts. We undertook div... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Expression Studies, Quantitative Genetics | Tanja Pyhäjärvi | 2018-11-23 11:57:35 | View | |

16 Dec 2020

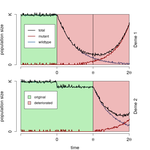

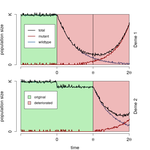

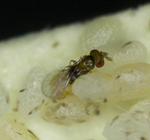

Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivityMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.092775The push and pull between theory and data in understanding the dynamics of invasionRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Laura Naslund and 2 anonymous reviewersExciting times are afoot for those of us interested in the ecology and evolution of invasive populations. Recent years have seen evolutionary process woven firmly into our understanding of invasions (Miller et al. 2020). This integration has inspired a welter of empirical and theoretical work. We have moved from field observations and verbal models to replicate experiments and sophisticated mathematical models. Progress has been rapid, and we have seen science at its best; an intimate discussion between theory and data. References Bîrzu, G., Matin, S., Hallatschek, O., and Korolev, K. S. (2019). Genetic drift in range expansions is very sensitive to density dependence in dispersal and growth. Ecology Letters, 22(11), 1817-1827. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13364 | Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken | <p>Range expansions are key processes shaping the distribution of species; their ecological and evolutionary dynamics have become especially relevant today, as human influence reshapes ecosystems worldwide. Many attempts to explain and predict ran... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Ben Phillips | 2020-08-04 12:51:56 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

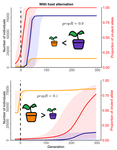

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance lociMetzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. 10.1111/evo.12854Evidence of epistasis provides further support to the Red Queen theory of host-parasite coevolutionRecommended by Adele Mennerat and Thierry LefèvreAccording to the Red Queen theory of antagonistic host-parasite coevolution, adaptation of parasites to the most common host genotype results in negative frequency-dependent selection whereby rare host genotypes are favoured. Assuming that host resistance relies on a genetic host-parasite (mis)match involving several linked loci, then recombination appears as much more efficient than parthenogenesis in generating new resistant host genotypes. This has long been proposed to explain one of the biggest so-called paradoxes in evolutionary biology, i.e. the maintenance of recombination despite its twofold cost. Evidence from various study systems indicates that successful infection (and hence host resistance) depends on a genetic match between the parasite’s and the host’s genotype via molecular interactions involving elicitor/receptor mechanisms. However the key assumption of epistasis, i.e. that this genetic host-parasite match involves several linked resistance loci, remained unsupported so far. Metzger and coauthors [1] now provide empirical support for it. Daphnia magna can reproduce both sexually and clonally and their well-studied interaction with Pasteuria ramosa makes them an excellent model system to investigate the genetics of host resistance. D. magna hosts were found to be either resistant (complete lack of attachment of parasite spores to the host’s foregut) or susceptible (full attachment). In this study the authors carried out an elegant Mendelian genetic investigation by performing multiple crosses between four host genotypes differing in their resistance to two different parasite isolates [1]. Their results show that resistance of D. magna to each of the two P. ramosa isolates relies on Mendelian inheritance at two loci that are linked (A and B), each of them having two alleles with dominant resistance; furthermore resistance to one parasite isolate confers susceptibility to the other. They also show that a third locus appears to confer double resistance (C), but that even double resistant hosts remain susceptible to other parasite isolates, and hence that universal host resistance is lacking – all of this supporting the Red Queen theory. This paper demonstrates with a high level of clarity that host resistance is governed by multiple linked loci. The assumption of epistasis between resistance loci is supported, which makes it possible for sexual recombination to be maintained by antagonistic host-parasite coevolution. Reference [1] Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. 2016. The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci. Evolution 70:480-487. doi: 10.1111/evo.12854 | The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci | Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. | A popular theory explaining the maintenance of genetic recombination (sex) is the Red Queen Theory. This theory revolves around the idea that time-lagged negative frequency-dependent selection by parasites favors rare host genotypes generated thro... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Adele Mennerat | 2016-12-14 13:58:53 | View | |

02 Jan 2019

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by EricaMichael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt https://doi.org/10.1101/290791The colonization history of largely isolated habitatsRecommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewersThe build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2]. References [1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790. | Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View | |

29 Sep 2017

Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continentMichael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou 10.1101/141127Unravelling the history of Neotropical plant diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Thomas Couvreur and Hervé SauquetSouth American rainforests, particularly the Tropical Andes, have been recognized as the hottest spot of plant biodiversity on Earth, while facing unprecedented threats from human impact [1,2]. Considerable research efforts have recently focused on unravelling the complex geological, bioclimatic, and biogeographic history of the region [3,4]. While many studies have addressed the question of Neotropical plant diversification using parametric methods to reconstruct ancestral areas and patterns of dispersal, Pirie et al. [5] take a distinct, complementary approach. Based on a new, near-complete molecular phylogeny of two Neotropical genera of the flowering plant family Annonaceae, the authors modelled the ecological niche of each species and reconstructed the history of niche differentiation across the region. The main conclusion is that, despite similar current distributions and close phylogenetic distance, the two genera experienced rather distinct processes of diversification, responding differently to the major geological events marking the history of the region in the last 20 million years (Andean uplift, drainage of Lake Pebas, and closure of the Panama Isthmus). As a researcher who has not personally worked on Neotropical biogeography, I found this paper captivating and especially enjoyed very much reading the Introduction, which sets out the questions very clearly. The strength of this paper is the near-complete diversity of species the authors were able to sample in each clade and the high-quality data compiled for the niche models. I would recommend this paper as a nice example of a phylogenetic study aimed at unravelling the detailed history of Neotropical plant diversification. While large, synthetic meta-analyses of many clades should continue to seek general patterns [4,6], careful studies restricted on smaller, but well controlled and sampled datasets such as this one are essential to really understand tropical plant diversification in all its complexity. References [1] Antonelli A, and Sanmartín I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414. [2] Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim JD, Brooks TB, Mittermeier CG, Lamoreux JL and Fonseca GAB. 2004. Hotspots revisited: Earths biologically richest and most endangered ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico City, Mexico 390pp [3] Antonelli A, Nylander JAA, Persson C and Sanmartín I. 2009. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 106, 9749–9754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811421106 [4] Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP, ter Steege H, Bermudez MA, Mora A, Sevink J, Sanmartín I, Sanchez-Meseguer A, Anderson CL, Figueiredo JP, Jaramillo C, Riff D, Negri FR, Hooghiemstra H, Lundberg J, Stadler T, Särkinen T and Antonelli A. 2010. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1194585 [5] Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut R, Melchers-Sharrott H and Chatrou L. 2017. Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent. bioRxiv, 141127, ver. 3 of 28th Sept 2017. doi: 10.1101/141127 [6] Bacon CD, Silvestro D, Jaramillo C, Tilston Smith B, Chakrabartye P and Antonelli A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 112, 6110–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423853112 | Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of the South American continent | Michael D. Pirie, Paul J. M. Maas, Rutger A. Wilschut, Heleen Melchers-Sharrott & Lars W. Chatrou | Much of the immense present day biological diversity of Neotropical rainforests originated from the Miocene onwards, a period of geological and ecological upheaval in South America. We assess the impact of the Andean orogeny, drainage of lake Peba... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Hervé Sauquet | Hervé Sauquet, Thomas Couvreur | 2017-06-03 21:25:48 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer