Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!

Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewer

The increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment.

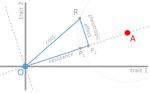

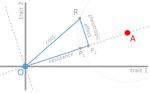

In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model.

The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies.

The authors highlight and explain the following points:

1. Costs of resistance do not necessarily imply pleiotropic effects of a resistance mutation, and pleiotropy is not necessarily the cause of fitness trade-offs.

2. Any non-treated environment and any treatment dose can result in a different cost.

3. Different reference genotypes may result in different costs. Specifically, the reference genotype has to be "optimally" adapted to the reference environment to provide an accurate measurement of costs.

Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations.

References

[1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675

[2] Andersson DI and Hughes D. Persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations. 2011. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 35: 901-911. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00289.x

[3] Chevereau G, Dravecká M, Batur T, Guvenek A, Ayhan DH, Toprak E, Bollenbach T. 2015. Quantifying the determinants of evolutionary dynamics leading to drug resistance. PLoS biology 13, e1002299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002299

[4] Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ. 2018. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 42: 68–80. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

[5] Hiltunen T, Virta M, Laine AL. 2017. Antibiotic resistance in the wild: an eco-evolutionary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 372: 20160039. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0039

| Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View |

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica

Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt

https://doi.org/10.1101/290791

The colonization history of largely isolated habitats

Recommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewers

The build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2].

To identify the biogeographic history and drivers of biogeographic movements of the large afrotemperate genus Erica, the study of Pirie and colleagues [3] develops a robust hypothesis-testing approach relying on historical biogeographic models, phylogenetic and species occurrence data. Specifically, the authors test the directionality of migrations through Africa and address the general question on whether geographic proximity or climatic niche similarity constrained the colonization of the Afrotemperate by Erica. They found that the distribution of Erica species in Africa is the result of infrequent colonization events and that both geographic proximity and niche similarity limited geographic movements (with the model that incorporates both factors fitting the data better than null models). Unfortunately, the correlation between geographic and environmental distances found in this study limited the potential evaluation of their roles individually. They also found that species of Erica have dispersed from Europe to African regions, with the Drakensberg Mountains representing a colonization sink, rather than acting as a “stepping stone” between the Cape and Tropical African regions.

Advances in historical biogeography have been recently questioned by the difficulty to compare biogeographic models emphasizing long distance dispersal (DEC+J) versus vicariance (DEC) using statistical methods, such as AIC, as well as by questioning the own performance of DEC+J models [4]. Behind Pirie et al. main conclusions prevails the assumption that patterns of concerted long distance dispersal are more realistic than vicariance scenarios, such that a widespread afrotemperate flora that receded with climatic changes never existed. Pirie et al. do not explicitly test for this scenario based on the idea that these habitats remained largely isolated over time and our current knowledge on African paleoclimates and vegetation, emphasizing the value of arguments based on empirical (biological, geographic) considerations in model comparisons. I, however, appreciate from this study that the results of the biogeographic models emphasizing long distance dispersal, vicariance, and the unconstrained models are congruent with each other and presented together.

Pirie and colleagues [3] bring a nice study on the importance of long distance dispersal and biome shift in structuring the regional floras of Africa. They evidence outstanding examples of radiations in Erica resulting from single dispersal events over long distances and between ecologically dissimilar areas, which highlight the importance of niche evolution and biome shifts in the assembly of diversity. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and model realism, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and environmental triggers are intertwined on shaping biological diversity. I found Pirie et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) very stimulating and hope that will help movement in that direction, providing interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions.

References

[1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790.

[2] Galley, C., Bytebier, B., Bellstedt, D. U., & Peter Linder, H. (2006). The Cape element in the Afrotemperate flora: from Cape to Cairo?. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274(1609), 535-543. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0046

[3] Pirie, M. D., Kandziora, M., Nuerk, N. M., Le Maitre, N. C., de Kuppler, A. L. M., Gehrke, B., Oliver, E. G. H., & Bellstedt, D. U. (2018). Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica. bioRxiv, 290791. ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/290791

[4] Ree, R. H., & Sanmartín, I. (2018). Conceptual and statistical problems with the DEC+ J model of founder‐event speciation and its comparison with DEC via model selection. Journal of Biogeography, 45(4), 741-749. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13173

| Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View |

Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic analysis of local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrum

Pratlong M, Haguenauer A, Brener K, Mitta G, Toulza E, Garrabou J, Bensoussan N, Pontarotti P, Aurelle D

https://doi.org/10.1101/306456

Pros and Cons of local adaptation scans

Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Lucas Gonçalves da Silva and 1 anonymous reviewer

The preprint by Pratlong et al. [1] is a well thought quest for genomic regions involved in local adaptation to depth in a species a red coral living the Mediterranean Sea. It first describes a pattern of structuration and then attempts to find candidate genes involved in local adaptation by contrasting deep with shallow populations. Although the pattern of structuration is clear and meaningful, the candidate genomic regions involved in local adaptation remain to be confirmed. Two external reviewers and myself found this preprint particularly interesting regarding the right-mindedness of the authors in front of the difficulties they encounter during their experiments. The discussions on the pros and cons of the approach are very sound and can be easily exported to a large number of studies that hunt for local adaptation. In this sense, the lessons one can learn by reading this well documented manuscript are certainly valuable for a wide range of evolutionary biologists.

More precisely, the authors RAD-sequenced 6 pairs of 'shallow vs deep' samples located in 3 geographical sea areas (Banyuls, Corsica and Marseilles). They were hoping to detect genes involved in the adaptation to depth, if there were any. They start by assessing the patterns of structuration of the 6 samples using PCA and AMOVA [2] and also applied the STRUCTURE [3] assignment software. They show clearly that the samples were mostly differentiated between geographical areas and that only 1 out the 3 areas shows a pattern of isolation by depth (i.e. Marseille). They nevertheless went on and scanned for variants that are highly differentiated in the deep samples when compared to the shallow paired samples in Marseilles, using an Fst outliers approach [4] implemented in the BayeScEnv software [5]. No clear functional signal was in the end detected among the highly differentiated SNPs, leaving a list of candidates begging for complementary data.

The scan for local adaptation using signatures of highly divergent regions is a classical problem of population genetics. It has been applied on many species with various degrees of success. This study is a beautiful example of a well-designed study that did not give full satisfactory answers. Readers will especially appreciate the honesty and the in-depth discussions of the authors while exposing their results and their conclusions step by step.

References

[1] Pratlong, M., Haguenauer, A., Brener, K., Mitta, G., Toulza, E., Garrabou, J., Bensoussan, N., Pontarotti P., & Aurelle, D. (2018). Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic scan for local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrum. bioRxiv, 306456, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/306456

[2] Excoffier, L., Smouse, P. E. & Quattro, J. M. (1992). Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics, 131(2), 479-491.

[3] Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M., & Donnelly, P. (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics, 155(2), 945-959.

[4] Lewontin, R. C., & Krakauer, J. (1973). Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics, 74(1), 175-195.

[5] de Villemereuil, P., & Gaggiotti, O. E. (2015). A new FST‐based method to uncover local adaptation using environmental variables. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 6(11), 1248-1258. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12418

| Separate the wheat from the chaff: genomic analysis of local adaptation in the red coral Corallium rubrum | Pratlong M, Haguenauer A, Brener K, Mitta G, Toulza E, Garrabou J, Bensoussan N, Pontarotti P, Aurelle D | <p>Genomic data allow an in-depth and renewed study of local adaptation. The red coral (Corallium rubrum, Cnidaria) is a highly genetically structured species and a promising model for the study of adaptive processes along an environmental gradien... |  | Adaptation, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | | 2018-04-24 11:27:40 | View |

Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frog

Rudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J.

https://doi.org/10.1101/314351

Tough as old boots: amphibians from drier habitats are more resistant to desiccation, but less flexible at exploiting wet conditions

Recommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Jennifer Nicole Lohr and 1 anonymous reviewer

Species everywhere are facing rapid climatic change, and we are increasingly asking whether populations will adapt, shift, or perish [1]. There is a growing realisation that, despite limited within-population genetic variation, many species exhibit substantial geographic variation in climate-relevant traits. This geographic variation might play an important role in facilitating adaptation to climate change [2,3].

Much of our understanding of geographic variation in climate-relevant traits comes from model organisms [e.g. 4]. But as our concern grows, we make larger efforts to understand geographic variation in non-model organisms also. If we understand what adaptive geographic variation exists within a species, we can make management decisions around targeted gene flow [5]. And as empirical examples accumulate, we can look for generalities that can inform management of unstudied species [e.g. 6,7]. Rudin-Bitterli’s paper [8] is an excellent contribution in this direction.

Rudin-Bitterli and her co-authors [8] sampled six frog populations distributed across a strong rainfall gradient. They then assayed these frogs and their offspring for a battery of fitness-relevant traits. The results clearly show patterns consistent with local adaptation to water availability, but they also reveal trade-offs. In their study, frogs from the driest source populations were resilient to the hydric environment: it didn’t really affect them very much whether they were raised in wet or dry environments. By contrast, frogs from wet source areas did better in wet environments, and they tended to do better in these wet environments than did animals from the dry-adapted populations. Thus, it appears that the resilience of the dry-adapted populations comes at a cost: frogs from these populations cannot ramp up performance in response to ideal (wet) conditions.

These data have been carefully and painstakingly collected, and they are important. They reveal not only important geographic variation in response to hydric stress (in a vertebrate), but they also adumbrate a more general trade-off: that the jack of all trades might be master of none. Specialist-generalist trade-offs are often argued (and regularly observed) to exist [e.g. 9,10], and here we see them arise in climate-relevant traits also. Thus, Rudin-Bitterli’s paper is an important piece of the empirical puzzle, and one that points to generalities important for both theory and management.

References

[1] Hoffmann, A. A., and Sgrò, C. M. (2011). Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature, 470(7335), 479–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09670

[2] Aitken, S. N., and Whitlock, M. C. (2013). Assisted Gene Flow to Facilitate Local Adaptation to Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 44(1), 367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135747

[3] Kelly, E., and Phillips, B. L. (2016). Targeted gene flow for conservation. Conservation Biology, 30(2), 259–267. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12623

[4] Sgrò, C. M., Overgaard, J., Kristensen, T. N., Mitchell, K. A., Cockerell, F. E., and Hoffmann, A. A. (2010). A comprehensive assessment of geographic variation in heat tolerance and hardening capacity in populations of Drosophila melanogaster from eastern Australia. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 23(11), 2484–2493. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02110.x

[5] Macdonald, S. L., Llewelyn, J., and Phillips, B. L. (2018). Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 21(2), 207–216. doi: 10.1111/ele.12883

[6] Hoffmann, A. A., Chown, S. L., and Clusella‐Trullas, S. (2012). Upper thermal limits in terrestrial ectotherms: how constrained are they? Functional Ecology, 27(4), 934–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02036.x

[7] Araújo, M. B., Ferri‐Yáñez, F., Bozinovic, F., Marquet, P. A., Valladares, F., and Chown, S. L. (2013). Heat freezes niche evolution. Ecology Letters, 16(9), 1206–1219. doi: 10.1111/ele.12155

[8] Rudin-Bitterli, T. S., Evans, J. P., and Mitchell, N. J. (2019). Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frog. BioRxiv, 314351, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/314351

[9] Kassen, R. (2002). The experimental evolution of specialists, generalists, and the maintenance of diversity. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15(2), 173–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00377.x

[10] Angilletta, M. J. J. (2009). Thermal Adaptation: A theoretical and empirical synthesis. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

| Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frog | Rudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J. | <p>Intra-specific variation in the ability of individuals to tolerate environmental perturbations is often neglected when considering the impacts of climate change. Yet this information is potentially crucial for mitigating any deleterious effects... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Ben Phillips | | 2018-05-07 03:35:08 | View |

Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emmanuelle d'Alencon, Nicolas Nègre

https://doi.org/10.1101/263186

Speciation through selection on mitochondrial genes?

Recommended by Astrid Groot based on reviews by Heiko Vogel and Sabine Haenniger

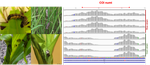

Whether speciation through ecological specialization occurs has been a thriving research area ever since Mayr (1942) stated this to play a central role. In herbivorous insects, ecological specialization is most likely to happen through host plant differentiation (Funk et al. 2002). Therefore, after Dorothy Pashley had identified two host strains in the Fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, in 1988 (Pashley 1988), researchers have been trying to decipher the evolutionary history of these strains, as this seems to be a model species in which speciation is currently occurring through host plant specialization. Even though FAW is a generalist, feeding on many different host plant species (Pogue 2002) and a devastating pest in many crops, Pashley identified a so-called corn strain and a so-called rice strain in Puerto Rico. Genetically, these strains were found to differ mostly in an esterase, although later studies showed additional genetic differences and markers, mostly in the mitochondrial COI and the nuclear TPI. Recent genomic studies showed that the two strains are overall so genetically different (2% of their genome being different) that these two strains could better be called different species (Kergoat et al. 2012). So far, the most consistent differences between the strains have been their timing of mating activities at night (Schoefl et al. 2009, 2011; Haenniger et al. 2019) and hybrid incompatibilities (Dumas et al. 2015; Kost et al. 2016). Whether and to what extent host plant preference or performance contributed to the differentiation of these sympatrically occurring strains has remained unclear.

In the current study, Orsucci et al. (2020) performed oviposition assays and reciprocal transplant experiments with both strains to measure fitness effects, in combination with a comprehensive RNAseq experiment, in which not only lab reared larvae were analysed, but also field-collected larvae. When testing preference and performance on the two host plants corn and rice, the authors did not find consistent fitness differences between the two strains, with both strains performing less on rice plants, although larvae from the corn strain survived more on corn plants than those from the rice strain. These results mostly confirm findings of a number of investigations over the past 30 years, where no consistent differences on the two host plants were observed (reviewed in Groot et al. 2016). However, the RNAseq experiments did show some striking differences between the two strains, especially in the reciprocally transplanted larvae, where both strains had been reared on rice or on corn plants for one generation: both strains showed transcriptional responses that correspond to their respective putative host plants, i.e. overexpression of genes involved in digestion and metabolic activity, and underexpression of genes involved in detoxification, in the corn strain on corn and in the rice strain on rice. Interestingly, similar sets of genes were found to be overexpressed in the field-collected larvae with which a RNAseq experiment was conducted as well.

The most interesting result of the study performed by Orsucci et al. (2020) is the underexpression in the corn strain of so-called numts, small genomic sequences that corresponded to fragments of the mitochondrial COI and COIII. These two numts were differentially expressed in the two strains in all RNAseq experiments analysed. This result coincides with the fact that the COI is one of the main diagnostic markers to distinguish these two strains. The authors suggestion that a difference in energy production between these two strains may be linked to a shift in host plant preference matches their finding that rice plants seem to be less suitable host plants than corn plants. However, as the lower suitability of rice plants was true for both strains, it remains unclear whether and how this difference could be linked to possible host plant differentiation between the strains. The authors also suggest that COI and potentially other mitochondrial genes may be the original target of selection between these two strains. This is especially interesting in light of the fact that field-collected larvae have frequently been found to have a rice strain mitochondrial genotype and a corn strain nuclear genotype, also in this study, while in the lab (female rice strain x male corn strain) hybrid females (i.e. females with a rice strain mitochondrial genotype and a corn strain nuclear genotype) are behaviorally sterile (Kost et al. 2016). Whether and how selection on mitochondrial genes or on mitonuclear interactions has indeed affected the evolution of these strains in the New world, and will affect the evolution of FAW in newly invaded habitats in the Old world, including Asia and Australia – where, so far, only corn strain and (female rice strain x male corn strain) hybrids have been found (Nagoshi 2019), will be a challenging research question for the coming years.

References

[1] Dumas, P. et al. (2015). Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host-plant variants: two host strains or two distinct species?. Genetica, 143(3), 305-316. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9829-2

[2] Funk, D. J., Filchak, K. E. and Feder J. L. (2002) Herbivorous insects: model systems for the comparative study of speciation ecology. In: Etges W.J., Noor M.A.F. (eds) Genetics of Mate Choice: From Sexual Selection to Sexual Isolation. Contemporary Issues in Genetics and Evolution, vol 9. Springer, Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0265-3_10

[3] Groot, A. T., Unbehend, M., Hänniger, S., Juárez, M. L., Kost, S. and Heckel D. G.(2016) Evolution of reproductive isolation of Spodoptera frugiperda. In Allison, J. and Cardé, R. (eds) Sexual communication in moths. Chapter 20: 291-300.

[4] Hänniger, S. et al. (2017). Genetic basis of allochronic differentiation in the fall armyworm. BMC evolutionary biology, 17(1), 68. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0911-5

[5] Kost, S., Heckel, D. G., Yoshido, A., Marec, F., and Groot, A. T. (2016). AZ‐linked sterility locus causes sexual abstinence in hybrid females and facilitates speciation in Spodoptera frugiperda. Evolution, 70(6), 1418-1427. doi: 10.1111/evo.12940

[6] Mayr, E. (1942) Systematics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York.

[7] Nagoshi, R. N. (2019). Evidence that a major subpopulation of fall armyworm found in the Western Hemisphere is rare or absent in Africa, which may limit the range of crops at risk of infestation. PloS one, 14(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208966

[8] Orsucci, M., Moné, Y., Audiot, P., Gimenez, S., Nhim, S., Naït-Saïdi, R., Frayssinet, M., Dumont, G., Boudon, J.-P., Vabre, M., Rialle, S., Koual, R., Kergoat, G. J., Nagoshi, R. N., Meagher, R. L., d’Alençon, E. and Nègre N. (2020) Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). bioRxiv, 263186, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/263186

[9] Pashley, D. P. (1988) Current Status of Fall Armyworm Host Strains. Florida Entomologist 71 (3): 227–34. doi: 10.2307/3495425

[10] Pogue, M. (2002). A World Revision of the Genus Spodoptera Guenée (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). American Entomological Society.

[11] Schöfl, G., Heckel, D. G., and Groot, A. T. (2009). Time‐shifted reproductive behaviours among fall armyworm (Noctuidae: Spodoptera frugiperda) host strains: evidence for differing modes of inheritance. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(7), 1447-1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01759.x

[12] Schöfl, G., Dill, A., Heckel, D. G., and Groot, A. T. (2011). Allochronic separation versus mate choice: nonrandom patterns of mating between fall armyworm host strains. The American Naturalist, 177(4), 470-485. doi: 10.1086/658904

| Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) | Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emm... | <p>Spodoptera frugiperda, the fall armyworm (FAW), is an important agricultural pest in the Americas and an emerging pest in sub-Saharan Africa, India, East-Asia and Australia, causing damage to major crops such as corn, sorghum and soybean. While... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Life History, Speciation | Astrid Groot | | 2018-05-09 13:04:34 | View |

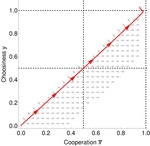

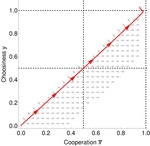

A nice twist on partner choice theory

Recommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

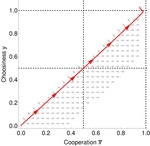

In this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff.

This study is a nice contribution to the literature that illustrates potential complexities with partner choice as a mechanism for cooperation, including how the proximate mechanisms of partner choice can significantly alter the evolutionary trajectory of cooperation. Modeling choice as a reaction norm that depends on one’s own traits also adds a layer of realism to partner choice theory.

The authors are also to be commended for the revisions they made through the review process. Earlier versions of the model somewhat overstated the tendency for fixed partner choice strategies to lead to over cooperation, missing some of the important features in previous models, notably McNamara et al. [2] that can counter this tendency. In this version, the authors acknowledge these factors, mainly, mortality during partner choice (which increases the opportunity cost of forgoing a current partner) and also the fact that endogenous distribution of alternative partners (which will tend to be worse than the overall population distribution, because more cooperative types spend more time attached and less cooperative types more time unattached). These two factors can constrain cooperation from “running away” as the authors put it, but the main point of Geoffroy et al. [1] that plastic choice can create selection against inefficient cooperation stands.

I think the paper will be very stimulating to theoretical and empirical researchers working on partner choice and social behaviors, and happy to recommend it.

References

[1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117

[2] McNamara, J. M., Barta, Z., Fromhage, L., & Houston, A. I. (2008). The coevolution of choosiness and cooperation. Nature, 451, 189–192. doi: 10.1038/nature06455

| Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View |

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes

Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo

https://doi.org/10.1101/337477

E5, the third oncogene of Papillomavirus

Recommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewer

Papillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts.

The PV genome consists of a double stranded circular DNA genome, roughly organized into three parts: an early region coding for six open reading frames (ORFs: E1, E2, E4, E5, E6 and E7) involved in multiple functions including viral replication and cell transformation; a late region coding for structural proteins (L1 and L2); and a non-coding regulatory region (URR) that contains the cis-elements necessary for replication and transcription of the viral genome.

The E5, E6, and E7 are known to act as oncogenes. The E6 protein binds to the cellular p53 protein [2]. The E7 protein binds to the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product, pRB [3]. However, the E5 has been poorly studied, even though a high correlation between the type of E5 protein and the infection phenotype is observed. E5s, being present on the E2/L2 intergenic region in the genomes of a few polyphyletic PV lineages, are so diverged and can only be characterized by high hydrophobicity. No similar sequences have been found in the sequence database.

Willemsen et al. [4] provide valuable evidence on the origin and evolutionary history of E5 genes and their genomic environments. First, they tested common ancestry vs independent origins [5]. Because alignment can lead to biased testing toward the hypothesis of common ancestry [6], they took full account of alignment uncertainty [7] and conducted random permutation test [8]. Although the strong chemical similarity hampered decisive conclusion on the test, they could confirm that E5 may do code proteins, and have unique evolutionary history with far different topology from the neighboring genes.

Still, there is mysteries with the origin and evolution of E5 genes. One of the largest interest may be the evolution of hydrophobicity, because it may be the main cause of variable infection phenotype. The inference has some similarity in nature with the inference of evolutionary history of G+C contents in bacterial genomes [9]. The inference may take account of possible opportunity of convergent or parallel evolution by setting an anchor to the topologies of neighboring genes.

References

[1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004

[2] Werness, B. A., Levine, A. J., & Howley, P. M. (1990). Association of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 E6 proteins with p53. Science, 248, 76-79. doi: 10.1126/science.2157286

[3] Dyson, N., Howley, P. M., Munger, K., & Harlow, E. D. (1989). The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science, 243, 934-937. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532

[4] Willemsen, A., Félez-Sánchez, M., & Bravo, I. G. (2019). Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes. bioRxiv, 337477, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/337477

[5] Theobald, D. L. (2010). A formal test of the theory of universal common ancestry. Nature, 465, 219–222. doi: 10.1038/nature09014

[6] Yonezawa, T., & Hasegawa, M. (2010). Was the universal common ancestry proved?. Nature, 468, E9. doi: 10.1038/nature09482

[7] Redelings, B. D., & Suchard, M. A. (2005). Joint Bayesian estimation of alignment and phylogeny. Systematic biology, 54(3), 401-418. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947041

[8] de Oliveira Martins, L., & Posada, D. (2014). Testing for universal common ancestry. Systematic biology, 63(5), 838-842. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu041

[9] Galtier, N., & Gouy, M. (1998). Inferring pattern and process: maximum-likelihood implementation of a nonhomogeneous model of DNA sequence evolution for phylogenetic analysis. Molecular biology and evolution, 15(7), 871-879. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025991

| Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View |

Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approach

Rubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez

https://doi.org/10.1101/356147

Sometimes, sex is in the head

Recommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Plants display an amazing diversity of reproductive strategies with and without sex. This diversity is particularly remarkable in flowering plants, as highlighted by Charles Darwin, who wrote several botanical books scrutinizing plant reproduction. One particularly influential work concerned floral variation [1]. Darwin recognized that flowers may present different forms within a single population, with or without sex specialization. The number of species concerned is small, but they display recurrent patterns, which made it possible for Darwin to invoke natural and sexual selection to explain them. Most of early evolutionary theory on the evolution of reproductive strategies was developed in the first half of the 20th century and was based on animals. However, the pioneering work by David Lloyd from the 1970s onwards excited interest in the diversity of plant sexual strategies as models for testing adaptive hypotheses and predicting reproductive outcomes [2]. The sex specialization of individual flowers and plants has since become one of the favorite topics of evolutionary biologists. However, attention has focused mostly on cases related to sex differentiation (dioecy and associated conditions [3]). Separate unisexual flower types on the same plant (monoecy and related cases, rendering the plant functionally hermaphroditic) have been much less studied, apart from their possible role in the evolution of dioecy [4] or their association with particular modes of pollination [5].

Two specific non-mutually exclusive hypotheses on the evolution of separate sexes in flowers (dicliny) have been proposed, both anchored in Lloyd’s views and Darwin’s legacy, with selfing avoidance and optimal limited resource allocation. Intermediate sex separation, in which sex morphs have different combinations of unisexual and hermaphrodite flowers, has been crucial for testing these hypotheses through comparative analyses of optimal conditions in suggested transitions. Again, cases in which floral unisexuality does not lead to sex separation have been studied much less than dioecious plants, at both the microevolutionary and macroevolutionary levels. It is surprising that the increasing availability of plant phylogenies and powerful methods for testing evolutionary transitions and correlations have not led to more studies, even though the frequency of monoecy is probably highest among diclinous species (those with unisexual flowers in any distribution among plants within a population [6]).

The study by Torices et al. [7] aims to fill this gap, offering a different perspective to that provided by Diggle & Miller [8] on the evolution of monoecious conditions. The authors use heads of a number of species of the sunflower family (Asteraceae) to test specifically the effect of resource limitation on the expression of sexual morphs within the head. They make use of the very particular and constant architecture of inflorescences in these species (the flower head or “capitulum”) and the diversity of sexual conditions (hermaphrodite, gynomonoecious, monoecious) and their spatial pattern within the flower head in this plant family to develop an elegant means of testing this hypothesis. Their results are consistent with their expectations on the effect of resource limitation on the head, as determined by patterns of fruit size within the head, assuming that female fecundity is more strongly limited by resource availability than male function.

The authors took on a huge challenge in choosing to study the largest plant family (about 25 thousand species). Their sample was limited to only about a hundred species, but species selection was very careful, to ensure that the range of sex conditions and the available phylogenetic information were adequately represented. The analytical methods are robust and cast no doubt on the reported results. However, I can’t help but wonder what would happen if the antiselfing hypothesis was tested simultaneously. This would require self-incompatibility (SI) data for the species sample, as the presence of SI is usually invoked as a powerful antiselfing mechanism, rendering the unisexuality of flowers unnecessary. However, SI is variable and frequently lost in the sunflower family [9]. I also wonder to what extent the very specific architecture of flower heads imposes an idiosyncratic resource distribution that may have fixed these sexual systems in species and lineages of the family. Although not approached in this study, intraspecific variation seems to be low. It would be very interesting to use similar approaches in other plant groups in which inflorescence architecture is lax and resource distribution may differ. A whole-plant approach might be required, rather than investigations of single inflorescences as in this study. This study has no flaws, but instead paves the way for further testing of a long-standing dual hypothesis, probably with different outcomes in different ecological and evolutionary settings. In the end, sex is not only in the head.

References

[1] Darwin, C. (1877). The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. John Murray.

[2] Barrett, S. C. H., and Harder, L. D. (2006). David G. Lloyd and the evolution of floral biology: from natural history to strategic analysis. In L.D. Harder, L. D., and Barrett, S. C. H. (eds) Ecology and Evolution of Flowers. OUP, Oxford. Pp 1-21.

[3] Geber, M. A., Dawson, T. E., and Delph, L. F. (eds) (1999). Gender and sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Springer, Berlin.

[4] Charlesworth, D. (1999). Theories of the evolution of dioecy. In Geber, M. A., Dawson T. E. and Delph L. F. (eds) (1999). Gender and sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Springer, Berlin. Pp. 33-60.

[5] Friedman, J., and Barrett, S. C. (2008). A phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of wind pollination in the angiosperms. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 169(1), 49-58. doi: 10.1086/523365

[6] Renner, S. S. (2014). The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database. American Journal of botany, 101(10), 1588-1596. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400196

[7] Torices, R., Afonso, A., Anderberg, A. A., Gómez, J. M., and Méndez, M. (2019). Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approach. bioRxiv, 356147, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/356147

[8] Diggle, P. K., and Miller, J. S. (2013). Developmental plasticity, genetic assimilation, and the evolutionary diversification of sexual expression in Solanum. American journal of botany, 100(6), 1050-1060. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200647

[9] Ferrer, M. M., and Good‐Avila, S. V. (2007). Macrophylogenetic analyses of the gain and loss of self‐incompatibility in the Asteraceae. New Phytologist, 173(2), 401-414. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01905.x

| Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approach | Rubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez | <p>Male and female unisexual flowers have repeatedly evolved from the ancestral bisexual flowers in different lineages of flowering plants. This sex specialization in different flowers often occurs within inflorescences. We hypothesize that inflor... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Juan Arroyo | Jana Vamosi, Marcial Escudero, Anonymous | 2018-06-27 10:49:52 | View |

A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps

D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi

https://doi.org/10.1101/342758

Genetic intimacy of filamentous viruses and endoparasitoid wasps

Recommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and 1 anonymous reviewer

Viruses establish intimate relationships with the cells they infect. The virocell is a novel entity, different from the original host cell and beyond the mere combination of viral and cellular genetic material. In these close encounters, viral and cellular genomes often hybridise, combine, recombine, merge and excise. Such chemical promiscuity leaves genomics scars that can be passed on to descent, in the form of deletions or duplications and, importantly, insertions and back and forth exchange of genetic material between viruses and their hosts.

In this preprint [1], Di Giovanni and coworkers report the identification of 13 genes present in the extant genomes of members of the Leptopilina wasp genus, bearing sound signatures of having been horizontally acquired from an ancestral virus. Importantly the authors identify Leptopilina boulardi filamentous virus (LbFV) as an extant relative of the ancestral virus that served as donor for the thirteen horizontally transferred genes. While pinpointing genes with a likely possible viral origin in eukaryotic genomes is only relatively rare, identifying an extant viral lineage related to the ancestral virus that continues to infect an extant relative of the ancestral host is remarkable. But the amazing evolutionary history of the Leptopilina hosts and these filamentous viruses goes beyond this shared genes. These wasps are endoparasitoids of Drosophila larvae, the female wasp laying the eggs inside the larvae and simultaneously injecting venom that hinders the immune response. The composition of the venoms is complex, varies between wasp species and also between individuals within a species, but a central component of all these venoms are spiked structures that vary in morphology, symmetry and size, often referred to as virus-like particles (VLPs).

In this preprint, the authors convincingly show that the expression pattern in the Leptopilina wasps of the thirteen genes identified to have been horizontally acquired from the LbFV ancestor coincides with that of the production of VLPs in the female wasp venom gland. Based on this spatio-temporal match, the authors propose that these VLPs have a viral origin. The data presented in this preprint will undoubtedly stimulate further research on the composition, function, origin, evolution and diversity of these VLP structures, which are highly debated (see for instance [2] and [3]).

References

[1] Di Giovanni, D., Lepetit, D., Boulesteix, M., Ravallec, M., & Varaldi, J. (2018). A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps. bioRxiv, 342758, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/342758

[2] Poirié, M., Colinet, D., & Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004

[3] Heavner, M. E., Ramroop, J., Gueguen, G., Ramrattan, G., Dolios, G., Scarpati, M., ... & Govind, S. (2017). Novel organelles with elements of bacterial and eukaryotic secretion systems weaponize parasites of Drosophila. Current Biology, 27(18), 2869-2877. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.019

| A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps | D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi | <p>To circumvent host immune response, numerous hymenopteran endo-parasitoid species produce virus-like structures in their reproductive apparatus that are injected into the host together with the eggs. These viral-like structures are absolutely n... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution | Ignacio Bravo | | 2018-07-18 15:59:14 | View |

Replication-independent mutations: a universal signature ?

Recommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Robert Lanfear

Mutations are the primary source of genetic variation, and there is an obvious interest in characterizing and understanding the processes by which they appear. One particularly important question is the relative abundance, and nature, of replication-dependent and replication-independent mutations - the former arise as cells replicate due to DNA polymerization errors, whereas the latter are unrelated to the cell cycle. A recent experimental study in fission yeast identified a signature of mutations in quiescent (=non-replicating) cells: the spectrum of such mutations is characterized by an enrichment in insertions and deletions (indels) compared to point mutations, and an enrichment of deletions compared to insertions [2].

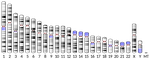

What Achaz et al. [1] report here is that the very same signature is detectable in humans. This time the approach is indirect and relies on two key aspects of mammalian reproduction biology: (1) oocytes remain quiescent over most of a female's lifespan, whereas spermatocytes keep dividing after male puberty, and (2) X chromosome, Y chromosome and autosomes spend different amounts of time in a female vs. male context. In agreement with the yeast study, Achaz et al. show that in humans the male-associated Y chromosome, for which quiescence is minimal, has by far the lowest ratios of indels to point mutations and of deletions to insertions, whereas the female-associated X chromosome has the highest. This is true both of variants that are polymorphic among humans and of fixed differences between humans and chimpanzees.

So we appear to be here learning about an important and general aspect of the mutation process. The authors suggest that, to a large extent, chromosomes tend to break in pieces at a rate that is proportional to absolute time - because indels in quiescent stage presumably result from double-strand DNA breaks. A very recent analysis of numerous mother-father-child trios in humans confirms this prediction in demonstrating an effect of maternal age, but not of paternal age, on the recombination rate [3]. This result also has important implications with respect to the interpretation of substitution rate variation among taxa and genomic compartments, particularly mitochondrial vs. nuclear, and their relationship with the generation time and longevity of organisms (e.g. [4]).

References

[1] Achaz, G., Gangloff, S., and Arcangioli, B. (2019). The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes. BioRxiv, 351288, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/351288

[2] Gangloff, S., Achaz, G., Francesconi, S., Villain, A., Miled, S., Denis, C., and Arcangioli, B. (2017). Quiescence unveils a novel mutational force in fission yeast. eLife, 6:e27469. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27469

[3] Halldorsson, B. V., Palsson, G., Stefansson, O. A., Jonsson, H., Hardarson, M. T., Eggertsson, H. P., … Stefansson, K. (2019). Characterizing mutagenic effects of recombination through a sequence-level genetic map. Science, 363: eaau1043. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1043

[4] Saclier, N., François, C. M., Konecny-Dupré, L., Lartillot, N., Guéguen, L., Duret, L., … Lefébure, T. (2019). Life History Traits Impact the Nuclear Rate of Substitution but Not the Mitochondrial Rate in Isopods. Molecular Biology and Evolution, in press. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy247

| The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes | Guillaume Achaz, Serge Gangloff, Benoit Arcangioli | <p>From the analysis of the mutation spectrum in the 2,504 sequenced human genomes from the 1000 genomes project (phase 3), we show that sexual chromosomes (X and Y) exhibit a different proportion of indel mutations than autosomes (A), ranking the... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Human Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | | 2018-07-25 10:37:48 | View |

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers