Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

20 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective RegimesHuang Y, Agrawal AF 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336Genetic adaptation counters phenotypic plasticity in experimental evolutionRecommended by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Stephanie BedhommeHow do phenotypic plasticity and adaptive evolution interact in a novel or changing environment? Does evolution by natural selection generally reinforce initially plastic phenotypic responses, or does it instead oppose them? And to what extent does evolution of a trait involve evolution of its plasticity? These questions have lied at the heart of research on phenotypic evolution in heterogeneous environments ever since it was realized that the environment is likely to affect the expression of many (perhaps most) characters of an individual. Importantly, this broad definition of phenotypic plasticity as change in the average phenotype of a given genotype in response to its environment of development (or expression) does not involve any statement about the adaptiveness of the plastic changes. Theory on the evolution of plasticity has devoted much effort to understanding how reaction norm should evolve under different regimes of environmental change in space and time, and depending on genetic constraints on reaction norm shapes. However on an empirically ground, the questions above have mostly been addressed for individual traits, often chosen a priori for their likeliness to exhibit adaptive plasticity, and we still lack more systematic answers. These can be provided by so-called ‘phenomic’ approaches, where a large number of traits are tracked without prior information on their biological or ecological function. A problem is that the number of phenotypic characters that can be measured in an organism is virtually infinite (and to some extent arbitrary), and that scaling issues makes it difficult to compare different sets of traits. Gene-expression levels offer a partial solution to this dilemma, as they can be considered as a very large number of traits (one per typed gene) that can be measured easily and uniformly (fold change in the number of reads in RNAseq). As for any traits, expression levels of different genes may be genetically correlated, to an extent that depends on their regulation mechanism: cis-regulatory sequences that only affect expression of neighboring genes are likely to cause independent gene expression, while more systematic modifiers of expression (e.g. trans-regulators such as transcription factors) may cause correlated genetic responses of the expression of many genes. Huang and Agrawal [1] have studied plasticity and evolution of gene expression level in young larvae of populations of Drosophila melanogaster that have evolved for about 130 generations under either a constant environment (salt or cadmium), or an environment that is heterogeneous in time or space (combining salt and cadmium). They report a wealth of results, of which we summarize the most striking here. First, among genes that (i) were initially highly plastic and (ii) evolved significant divergence in expression levels between constant environment treatments, the evolved divergence is predominantly in the opposite direction to the initial plastic response. This suggests that either plasticity was initially maladaptive, or the selective pressure changed during the evolutionary process (see below). This somewhat unexpected result strikingly mirrors that from a study published last year in Nature [2], where the same pattern was found for responses of guppies to the presence of predators. However, Huang and Agrawal [1] went beyond this study by deciphering the underlying mechanisms in several interesting ways. First, they showed that change in gene expression often occurred at genes close to SNPs with differentiated frequencies across treatments (but not at genes with differentiated SNPs in their coding sequences), suggesting that cis-regulatory sequences are involved. This is also suggested by the fact that changes in gene expression are mostly caused by the increased expression of only one allele at polymorphic loci, and is a first step towards investigating the genetic underpinnings of (co)variation in gene expression levels. Another interesting set of findings concerns evolution of plasticity in treatments with variable environments. To compare the gene-expression plasticity that evolved in these treatments to an expectation, the authors considered that the expression levels in populations maintained for a long time under constant salt or cadmium had reached an optimum. The differences between these expression levels were thus assumed to predict the level of plasticity that should evolve in a heterogeneous environment (with both cadmium and salt) under perfect environmental predictability. The authors showed that plasticity did evolve more in the expected direction in heterogeneous than in constant environments, resulting in better adapted final expression levels across environments. Taken collectively, these results provide an unprecedented set of patterns that are greatly informative on how plasticity and evolution interact in constant versus changing environments. But of course, interpretations in terms of adaptive versus maladaptive plasticity are more challenging, as the authors themselves admit. Even though environmentally determined gene expression is the basic mechanism underlying the phenotypic plasticity of most traits, it is extremely difficult to relate to more integrated phenotypes for which we can understand the selection pressures, especially in multicellular organisms. The authors have recently investigated evolutionary change of quantitative traits in these selected lines, so it might be possible to establish links between reaction norms for macroscopic traits to those for gene expression levels. Such an approach would also involve tracking gene expression throughout life, rather than only in young larvae as done here, thus putting phenotypic complexity back in the picture also for expression levels. Another difficulty is that a plastic response that was originally adaptive may be replaced by an opposite evolutionary response in the long run, without having to invoke initially maladaptive plasticity. For instance, the authors mention the possibility that a generic stress response is initially triggered by cadmium, but is eventually unnecessary and costly after evolution of genetic mechanisms for cadmium detoxification (a case of so-called genetic accommodation). In any case, this study by Huang and Agrawal [1], together with the one by Ghalambor et al. last year [2], reports novel and unexpected results, which are likely to stimulate researchers interested in plasticity and evolution in heterogeneous environments for the years to come. References [1] Huang Y, Agrawal AF. 2016. Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes. PLoS Genetics 12:e1006336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336 [2] Ghalambor CK, Hoke KL, Ruell EW, Fischer EK, Reznick DN, Hughes KA. 2015. Non-adaptive plasticity potentiates rapid adaptive evolution of gene expression in nature. Nature 525: 372-375. doi: 10.1038/nature15256 | Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes | Huang Y, Agrawal AF | Little is known of how gene expression and its plasticity evolves as populations adapt to different environmental regimes. Expression is expected to evolve adaptively in all populations but only those populations experiencing environmental heterog... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Expression Studies, Phenotypic Plasticity | Luis-Miguel Chevin | 2016-12-20 09:04:15 | View | |

08 Jan 2024

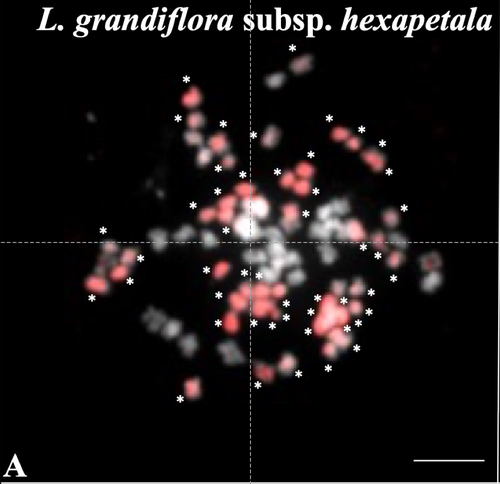

Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigationsD. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458Deciphering the genomic composition of tetraploid, hexaploid and decaploid Ludwigia L. species (section Jussiaea)Recommended by Malika AINOUCHE based on reviews by Alex BAUMEL and Karol MARHOLDPolyploidy, which results in the presence of more than two sets of homologous chromosomes represents a major feature of plant genomes that have undergone successive rounds of duplication followed by more or less rapid diploidization during their evolutionary history. Polyploid complexes containing diploid and derived polyploid taxa are excellent model systems for understanding the short-term consequences of whole genome duplication, and have been particularly well-explored in evolutionary ecology (Ramsey and Ramsey 2014, Rice et al. 2019). Many polyploids (especially when resulting from interspecific hybridization, i.e. allopolyploids) are successful invaders (te Beest et al. 2012) as a result of rapid genome dynamics, functional novelty, and trait evolution. The origin (parental legacy) and modes of formation of polyploids have a critical impact on the subsequent polyploid evolution. Thus, elucidation of the genomic composition of polyploids is fundamental to understanding trait evolution, and such knowledge is still lacking for many invasive species. Genus Ludwigia is characterized by a complex taxonomy, with an underexplored evolutionary history. Species from section Jussieae form a polyploid complex with diploids, tetraploids, hexaploids, and decaploids that are notorious invaders in freshwater and riparian ecosystems (Thouvenot et al.2013). Molecular phylogeny of the genus based on nuclear and chloroplast sequences (Liu et al. 2027) suggested some relationships between diploid and polyploid species, without fully resolving the question of the parentage of the polyploids. In their study, Barloy et al. (2023) have used a combination of molecular cytogenetics (Genomic In situ Hybridization), morphology and experimental crosses to elucidate the genomic compositions of the polyploid species, and show that the examined polyploids are of hybrid origin (allopolyploids). The tetraploid L. stolonifera derives from the diploids L. peploides subsp. montevidensis (AA genome) and L. helminthorhiza (BB genome). The tetraploid L. ascendens also share the BB genome combined with an undetermined different genome. The hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. grandiflora has inherited the diploid AA genome combined with additional unidentified genomes. The decaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala has inherited the tetraploid L. stolonifera and the hexaploid L. grandiflora subsp. hexapetala genomes. As the authors point out, further work is needed, including additional related diploid (e.g. other subspecies of L. peploides) or tetraploid (L. hookeri and L. peduncularis) taxa that remain to be investigated, to address the nature of the undetermined parental genomes mentioned above. The presented work (Barloy et al. 2023) provides significant knowledge of this poorly investigated group with regard to genomic information and polyploid origin, and opens perspectives for future studies. The authors also detect additional diagnostic morphological traits of interest for in-situ discrimination of the taxa when monitoring invasive populations. References Barloy D., Portillo-Lemus L., Krueger-Hadfield S.A., Huteau V., Coriton O. (2024). Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus Ludwigia L. section Jussiaea using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.02.522458 te Beest M., Le Roux J.J., Richardson D.M., Brysting A.K., Suda J., Kubešová M., Pyšek P. (2012). The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Annals of Botany, Volume 109, Issue 1 Pages 19–45, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcr277 Ramsey J. and Ramsey T. S. (2014). Ecological studies of polyploidy in the 100 years following its discovery Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B369 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0352 Rice, A., Šmarda, P., Novosolov, M. et al. (2019). The global biogeography of polyploid plants. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0787-9 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G. (2013). A success story: Water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 23:790–803 https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 | Genomic relationships among diploid and polyploid species of the genus *Ludwigia* L. section *Jussiaea* using a combination of molecular cytogenetic, morphological, and crossing investigations | D. Barloy, L. Portillo - Lemus, S. A. Krueger-Hadfield, V. Huteau, O. Coriton | <p>ABSTRACTThe genus Ludwigia L. sectionJussiaeais composed of a polyploid species complex with 2x, 4x, 6x and 10x ploidy levels, suggesting possible hybrid origins. The aim of the present study is to understand the genomic relationships among dip... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Malika AINOUCHE | 2023-01-11 13:47:18 | View | |

06 Oct 2017

Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebratesFrancisco J. Novo https://doi.org/10.1101/150482Combining molecular information on chromatin organisation with eQTLs and evolutionary conservation provides strong candidates for the evolution of gene regulation in mammalian brainsRecommended by Marc Robinson-Rechavi based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Charles DankoIn this manuscript [1], Francisco J. Novo proposes candidate non-coding genomic elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes. What is very nice about this study is the way in which public molecular data, including physical interaction data, is used to leverage recent advances in our understanding to molecular mechanisms of gene regulation in an evolutionary context. More specifically, evolutionarily conserved non coding sequences are combined with enhancers from the FANTOM5 project, DNAse hypersensitive sites, chromatin segmentation, ChIP-seq of transcription factors and of p300, gene expression and eQTLs from GTEx, and physical interactions from several Hi-C datasets. The candidate regulatory regions thus identified are linked to candidate regulated genes, and the author shows their potential implication in brain development. While the results are focused on a small number of genes, this allows to verify features of these candidates in great detail. This study shows how functional genomics is increasingly allowing us to fulfill the promises of Evo-Devo: understanding the molecular mechanisms of conservation and differences in morphology. References [1] Novo, FJ. 2017. Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 150482, ver. 4 of Sept 29th, 2017. doi: 10.1101/150482 | Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates | Francisco J. Novo | <p>Many non-coding regulatory elements conserved in vertebrates regulate the expression of genes involved in development and play an important role in the evolution of morphology through the rewiring of developmental gene networks. Available biolo... |  | Genome Evolution | Marc Robinson-Rechavi | Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Charles Danko | 2017-06-29 08:55:41 | View |

03 Apr 2020

Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen https://doi.org/10.1101/662577Genomic structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaiceRecommended by Maren Wellenreuther based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersAwareness has been growing that structural variants in the genome of species play a fundamental role in adaptive evolution and diversification [1]. Here, Le Moan and co-authors [2] report empirical genomic-wide SNP data on the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) across a major environmental transmission zone, ranging from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea. Regions of high linkage disequilibrium suggest the presence of two structural variants that appear to have evolved 220 kya. These two putative structural variants show weak signatures of isolation by distance when contrasted against the rest of the genome, but the frequency of the different putative structural variants appears to co-vary in some parts of the studied range with the environment, indicating the involvement of both selective and neutral processes. This study adds to the mounting body of evidence that structural genomic variants harbour significant information that allows species to respond and adapt to the local environmental context. References [1] Wellenreuther, M., Mérot, C., Berdan, E., & Bernatchez, L. (2019). Going beyond SNPs: the role of structural genomic variants in adaptive evolution and species diversification. Molecular ecology, 28(6), 1203-1209. doi: 10.1111/mec.15066 | Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) | Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen | <p>Changing environmental conditions can lead to population diversification through differential selection on standing genetic variation. Structural variant (SV) polymorphisms provide examples of ancient alleles that in time become associated with... | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Maren Wellenreuther | 2019-07-13 12:44:01 | View | ||

16 Nov 2018

Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen IslandsChristelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil https://doi.org/10.1101/239244Introgression from related species reveals fine-scale structure in an isolated population of mussels and causes patterns of genetic-environment associationsRecommended by Marianne Elias based on reviews by Thomas Broquet and Tatiana GiraudAssessing population connectivity is central to understanding population dynamics, and is therefore of great importance in evolutionary biology and conservation biology. In the marine realm, the apparent absence of physical barriers, large population sizes and high dispersal capacities of most organisms often result in no detectable structure, thereby hindering inferences of population connectivity. In a review paper, Gagnaire et al. [1] propose several ideas to improve detection of population connectivity. Notably, using simulations they show that under certain circumstances introgression from one species into another may reveal cryptic population structure within that second species. References [1] Gagnaire, P.-A., Broquet, T., Aurelle, D., Viard, F., Souissi, A., Bonhomme, F., Arnaud-Haond, S., & Bierne, N. (2015). Using neutral, selected, and hitchhiker loci to assess connectivity of marine populations in the genomic era. Evolutionary Applications, 8, 769–786. doi: 10.1111/eva.12288 | Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen Islands | Christelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil | <p>Reticulated evolution -i.e. secondary introgression / admixture between sister taxa- is increasingly recognized as playing a key role in structuring infra-specific genetic variation and revealing cryptic genetic connectivity patterns. When admi... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Marianne Elias | 2017-12-28 14:16:16 | View | |

20 May 2020

How much does Ne vary among species?Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle https://doi.org/10.1101/861849Further questions on the meaning of effective population sizeRecommended by Martin Lascoux based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIn spite of its name, the effective population size, Ne, has a complex and often distant relationship to census population size, as we usually understand it. In truth, it is primarily an abstract concept aimed at measuring the amount of genetic drift occurring in a population at any given time. The standard way to model random genetic drift in population genetics is the Wright-Fisher model and, with a few exceptions, definitions of the effective population size stems from it: “a certain model has effective population size, Ne, if some characteristic of the model has the same value as the corresponding characteristic for the simple Wright-Fisher model whose actual size is Ne” (Ewens 2004). Since Sewall Wright introduced the concept of effective population size in 1931 (Wright 1931), it has flourished and there are today numerous definitions of it depending on the process being examined (genetic diversity, loss of alleles, efficacy of selection) and the characteristic of the model that is considered. These different definitions of the effective population size were generally introduced to address specific aspects of the evolutionary process. One aspect that has been hotly debated since the first estimates of genetic diversity in natural populations were published is the so-called Lewontin’s paradox (1974). Lewontin noted that the observed variation in heterozygosity across species was much smaller than one would expect from the neutral expectations calculated with the actual size of the species. References Brandvain Y, Wright SI (2016) The Limits of Natural Selection in a Nonequilibrium World. Trends in Genetics, 32, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.004 | How much does Ne vary among species? | Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle | <p>Genetic drift is an important evolutionary force of strength inversely proportional to *Ne*, the effective population size. The impact of drift on genome diversity and evolution is known to vary among species, but quantifying this effect is a d... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Martin Lascoux | 2019-12-08 00:11:00 | View | |

22 Sep 2020

Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primatesRylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/445072Studying genetic antagonisms as drivers of genome evolutionRecommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Qi Zhou and 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes are special in the genome because they are often highly differentiated over much of their lengths and marked by degenerative evolution of their gene content. Understanding why sex chromosomes differentiate requires deciphering the forces driving their recombination patterns. Suppression of recombination may be subject to selection, notably because of functional effects of locking together variation at different traits, as well as longer-term consequences of the inefficient purge of deleterious mutations, both of which may contribute to patterns of differentiation [1]. As an example, male and female functions may reveal intrinsic antagonisms over the optimal genotypes at certain genes or certain combinations of interacting genes. As a result, selection may favour the recruitment of rearrangements blocking recombination and maintaining the association of sex-antagonistic allele combinations with the sex-determining locus. References [1] Charlesworth D (2017) Evolution of recombination rates between sex chromosomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160456. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0456 | Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates | Rylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais | <p>Sex chromosomes are typically comprised of a non-recombining region and a recombining pseudoautosomal region. Accurately quantifying the relative size of these regions is critical for sex chromosome biology both from a functional (i.e. number o... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Mathieu Joron | 2019-02-04 15:16:32 | View | |

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

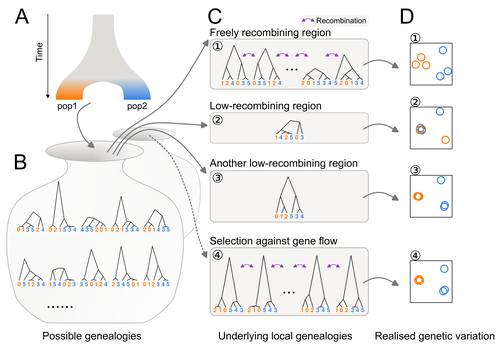

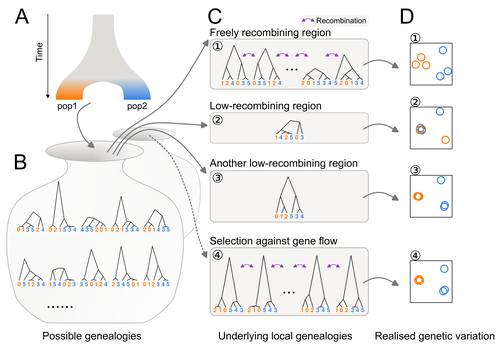

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

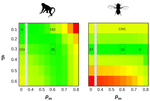

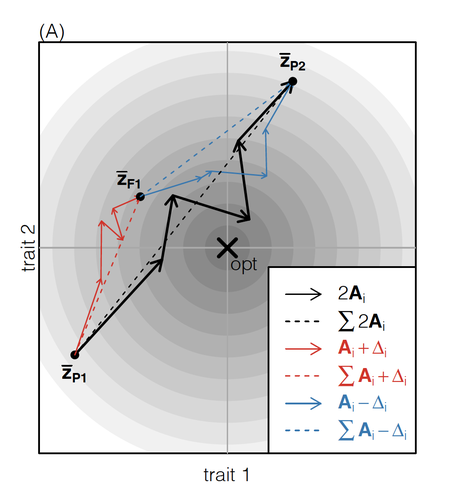

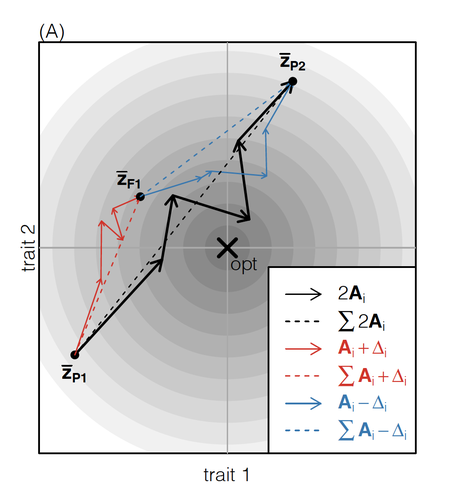

How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation?Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483443A general model of fitness effects following hybridisationRecommended by Matthew Hartfield based on reviews by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Juan LiStudying the effects of speciation, hybridisation, and evolutionary outcomes following reproduction from divergent populations is a major research area in evolutionary genetics [1]. There are two phenomena that have been the focus of contemporary research. First, a classic concept is the formation of ‘Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller’ incompatibilities (BDMi) [2–4] that negatively affect hybrid fitness. Here, two diverging populations accumulate mutations over time that are unique to that subpopulation. If they subsequently meet, then these mutations might negatively interact, leading to a loss in fitness or even a complete lack of reproduction. BDMi formation can be complex, involving multiple genes and the fitness changes can depend on the direction of introgression [5]. Second, such secondary contact can instead lead to heterosis, where offspring are fitter than their parental progenitors [6]. Understanding which outcomes are likely to arise require one to know the potential fitness effects of mutations underlying reproductive isolation, to determine whether they are likely to reduce or enhance fitness when hybrids are formed. This is far from an easy task, as it requires one to track mutations at several loci, along with their effects, across a fitness landscape. The work of De Sanctis et al. [7] neatly fills in this knowledge gap, by creating a general mathematical framework for describing the consequences of a cross from two divergent populations. The derivations are based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, which is widely used to quantify selection acting on a general fitness landscape that is affected by several biological traits [8,9], and has previously been used in theoretical studies of hybridisation [10–12]. By doing so, they are able to decompose how divergence at multiple loci affects offspring fitness through both additive and dominance effects. A key result arising from their analyses is demonstrating how offspring fitness can be captured by two main functions. The first one is the ‘net effect of evolutionary change’ that, broadly defined, measures how phenotypically divergent two populations are. The second is the ‘total amount of evolutionary change’, which reflects how many mutations contribute to divergence and the effect sizes captured by each of them. The authors illustrate these measurements using simulations covering different scenarios, demonstrating how different parental states can lead to similar fitness outcomes. They also propose experimental methods to measure the underlying mutational effects. This study neatly demonstrates how complex genetic phenomena underlying hybridisation can be captured using fairly simple mathematical formulae. This powerful approach will thus open the door for future research to investigate hybridisation in more detail, whether it is by expanding on these theoretical models or using the elegant outcomes to quantify fitness effects in experiments.

References 1. Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2004. | How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation? | Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch | <p>When divergent populations interbreed, the outcome will be affected by the genomic and phenotypic differences that they have accumulated. In this way, the mode of evolutionary divergence between populations may have predictable consequences for... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Matthew Hartfield | 2022-03-30 14:55:46 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer

, where Ne is the effective population size and

, where Ne is the effective population size and  is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common

is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common  . Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.

. Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.