Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

25 Jan 2023

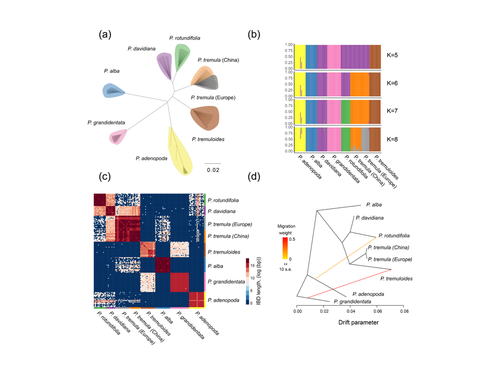

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View | |

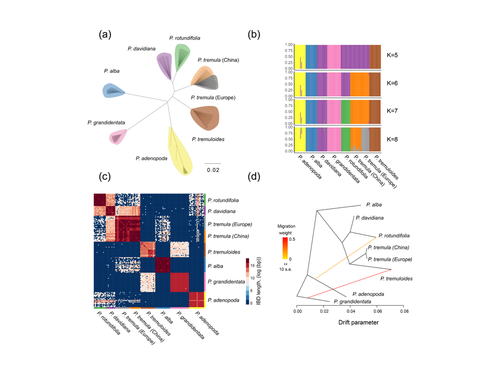

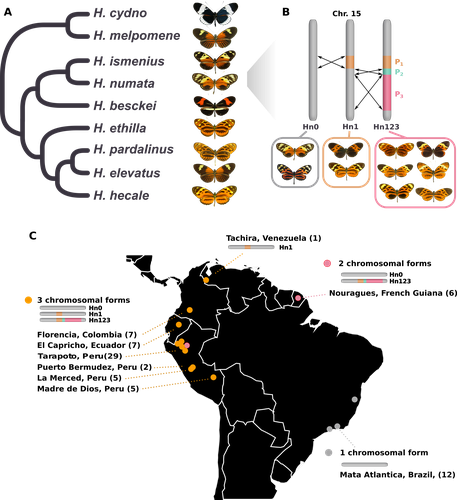

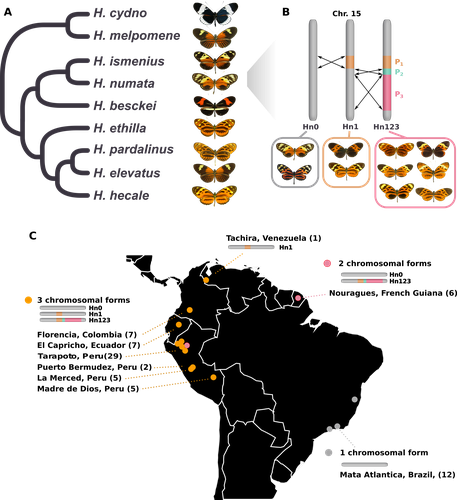

30 Mar 2023

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterflyMaría Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, Mathieu Joron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea. The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale. Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding. REFERENCES Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348 | Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly | María Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Selection shapes genetic diversity around target mutations, yet little is known about how selection on specific loci affects the genetic trajectories of populations, including their genomewide patterns of diversity ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Chris Jiggins | 2021-10-13 17:54:33 | View | |

29 Nov 2022

Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic dataVitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133Inference of genome-wide processes using temporal population genomic dataRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio and 2 anonymous reviewersEvolutionary genomics, and population genetics in particular, aim to decipher the respective influence of neutral and selective forces shaping genetic polymorphism in a species/population. This is a much-needed requirement before scanning genome data for footprints of species adaptation to their biotic and abiotic environment (Johri et al. 2022). In general, we would like to quantify the proportion of the genome evolving neutrally and under selective (positive, balancing and negative) pressures (Kern and Hahn 2018, Johri et al. 2021). We thus need to understand patterns of linked selection along the genome, that is how the distribution of genetic polymorphisms is shaped by selected sites and the recombination landscape. The present contribution by Pavinato et al. (2022) provides an additional method in the population genomics toolbox to quantify the extent of linked positive and negative selection using temporal data. The availability of genomics data for model and non-model species has led to improvement of the modeling framework for demography and selection (Johri et al. 2022), but also new inference methods making use of the full genome data based on the Sequential Markovian Coalescent (SMC, Li and Durbin 2011), Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC, Jay et al. 2019), ABC and machine learning (Pudlo et al. 2016, Raynal et al. 2019) or Deep Learning (Sanchez et al. 2021). These methods are based on one sample in time and the use of the coalescent theory to reconstruct the past (demographic) history. However, it is also possible to obtain for many species temporal data sampled over several time points. For species with short generation time (in experimental evolution or monitored populations), one can sample a population every couple of generations as exemplified with Drosophila melanogaster (Bergland et al. 2010). For species with longer generation times that cannot be easily regularly sampled in time, it becomes possible to sequence available specimens from museums (e.g. Cridland et al. 2018) or ancient DNA samples. Methods using temporal data are based on the classical population genomics assumption that demography (migration, population subdivision, population size changes) leaves a genome-wide signal, while selection leaves a localized signal in the close vicinity of the causal mutation. Several methods do assess the demography of a population (change in effective population size, Ne, in time) using temporal data (e.g. Jorde and Ryman 2007) which can be used to calibrate the detection of loci under strong positive selection (Foll et al. 2014). Recently Buffalo and Coop (2020) used genome-wide covariance between allele frequency changes across time samples (and across replicates) to quantify the effects of linked selection over short timescales. In the present contribution, Pavinato et al. (2022) make use of temporal data to draw the joint estimation of demographic and selective parameters using a simulation-based method (ABC-Random Forests). This study by Pavinato et al. (2022) builds a framework allowing to infer the census size of the population in time (N) separately from the effect of genetic drift, which is determined by change in effective population size (Ne) in time, as well estimates of genome-wide parameters of selection. In a nutshell, the authors use a forward simulator and summarize genome data by genomic windows using classic statistics (nucleotide diversity, Tajima’s D, FST, heterozygosity) between time samples and for each sample. They specifically use the distributions (higher moments) of these statistics among all windows. The authors combine as input for the ABC-RF, vectors of summary statistics, model parameters and five latent variables: Ne, the ratio Ne/N, the number of beneficial mutations under strong selection, the average selection coefficient of strongly selected mutations, and the average substitution load. Indeed, the authors are interested in three different types of selection components: 1) the adaptive potential of a population which is estimated as the population mutation rate of beneficial mutations (θb), 2) the number of mutations under strong selection (irrespective of whether they reached fixation or not), and 3) the overall population fitness which is a function of the genetic load. In other words, the novelty of this method is not to focus on the detection of loci under selection, but to infer key parameters/distributions summarizing the genome-wide signal of demography and (positive and negative) selection. As a proof of principle, the authors then apply their method to a dataset of feral populations of honey bees (Apis mellifera) collected in California across many years and recovered from Museum samples (Cridland et al. 2018). The approach yields estimates of Ne which are on the same order of magnitude of previous estimates in hymenopterans, and the authors discuss why the different populations show various values of Ne and N which can be explained by different history of admixture with wild but also domesticated lineages of bees. This study focuses on quantifying the genome-wide joint footprints of demography, and strong positive and negative selection to determine which proportion of the genome evolves neutrally or not. Further application of this method can be anticipated, for example, to study species with ecological and life-history traits which generate discrepancies between census size and Ne, for example for plants with selfing or seed banking (Sellinger et al. 2020), and for which the genome-wide effect of linked selection is not fully understood. References Johri P, Aquadro CF, Beaumont M, Charlesworth B, Excoffier L, Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD, Lynch M, McVean G, Payseur BA, Pfeifer SP, Stephan W, Jensen JD (2022) Recommendations for improving statistical inference in population genomics. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001669 Kern AD, Hahn MW (2018) The Neutral Theory in Light of Natural Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy092 Johri P, Riall K, Becher H, Excoffier L, Charlesworth B, Jensen JD (2021) The Impact of Purifying and Background Selection on the Inference of Population History: Problems and Prospects. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 2986–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab050 Pavinato VAC, Mita SD, Marin J-M, Navascués M de (2022) Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data. bioRxiv, 2021.03.12.435133, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133 Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475, 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 Jay F, Boitard S, Austerlitz F (2019) An ABC Method for Whole-Genome Sequence Data: Inferring Paleolithic and Neolithic Human Expansions. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz038 Pudlo P, Marin J-M, Estoup A, Cornuet J-M, Gautier M, Robert CP (2016) Reliable ABC model choice via random forests. Bioinformatics, 32, 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv684 Raynal L, Marin J-M, Pudlo P, Ribatet M, Robert CP, Estoup A (2019) ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35, 1720–1728. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F (2021) Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, 21, 2645–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224 Bergland AO, Behrman EL, O’Brien KR, Schmidt PS, Petrov DA (2014) Genomic Evidence of Rapid and Stable Adaptive Oscillations over Seasonal Time Scales in Drosophila. PLOS Genetics, 10, e1004775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004775 Cridland JM, Ramirez SR, Dean CA, Sciligo A, Tsutsui ND (2018) Genome Sequencing of Museum Specimens Reveals Rapid Changes in the Genetic Composition of Honey Bees in California. Genome Biology and Evolution, 10, 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evy007 Jorde PE, Ryman N (2007) Unbiased Estimator for Genetic Drift and Effective Population Size. Genetics, 177, 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.107.075481 Foll M, Shim H, Jensen JD (2015) WFABC: a Wright–Fisher ABC-based approach for inferring effective population sizes and selection coefficients from time-sampled data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12280 Buffalo V, Coop G (2020) Estimating the genome-wide contribution of selection to temporal allele frequency change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 20672–20680. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919039117 Sellinger TPP, Awad DA, Moest M, Tellier A (2020) Inference of past demography, dormancy and self-fertilization rates from whole genome sequence data. PLOS Genetics, 16, e1008698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008698 | Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data | Vitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués | <p style="text-align: justify;">Disentangling the effects of selection and drift is a long-standing problem in population genetics. Simulations show that pervasive selection may bias the inference of demography. Ideally, models for the inference o... |  | Adaptation, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2021-10-20 09:41:26 | View | |

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

02 Nov 2022

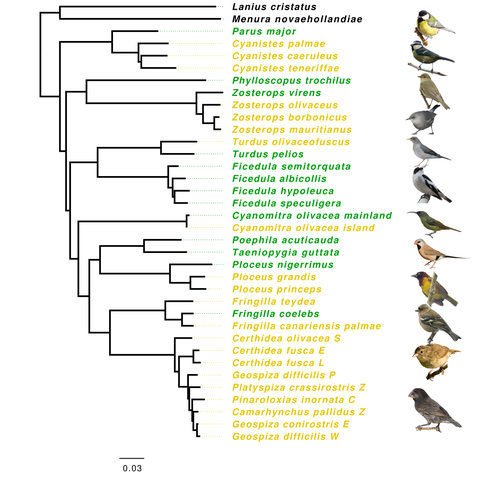

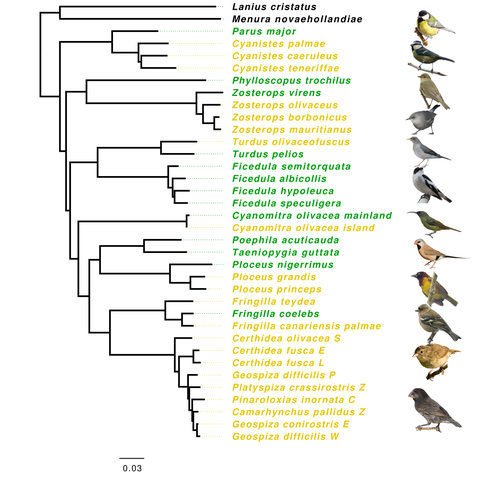

Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndromeMathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450Demographic effects may affect adaptation to islandsRecommended by Emma Berdan based on reviews by Steven Fiddaman and 3 anonymous reviewersThe unique challenges associated with living on an island often result in organisms displaying a specific suite of traits commonly referred to as “island syndrome” (Adler and Levins, 1994; Burns, 2019; Baeckens and Van Damme, 2020). Large phenotypic shifts such as changes in size (e.g. shifts to gigantism or dwarfism, Lomolino, 2005) or coloration (Doutrelant et al., 2016) abound in the literature. However, less obvious phenotypes may also play a key role in adaptation to islands. One such trait, reduced immune function, has important implications for the future of island populations in the face of anthropogenic-induced changes. Due to lower parasite pressure caused by a less diverse and less virulent parasite population, island hosts may show a decrease in immune defenses (Beadell et al., 2006; Pérez‐Rodríguez et al., 2013). However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as many studies have found ambiguous or conflicting results (Matson, 2006; Illera et al., 2015). While most previous work has examined various immunological parameters (e.g., antibody concentrations), here, Barthe et al. (2022) take the novel approach of examining molecular signatures of immune genes. Using comparative genomic data from 34 different species of birds the authors examine the ratio of synonymous substitutions (i.e., not changing an amino acid) to non-synonymous substitutions (i.e., changing an amino acid) in innate and acquired immune genes (Pn/Ps ratio). Because population sizes on islands are lower which will affect molecular evolution, they compare these results to data from 97 control genes. Assuming relaxed selection on islands predicts that the difference between the Pn/Ps ratio of immune genes and of control genes (ΔPn/Ps) is greater in island species compared to mainland ones. As with previous work the authors found that the results differ depending on the category of immune genes. Both forms of innate defense: beta-defensins and Toll-like receptors did not show higher ΔPn/Ps for island populations. As these genes still have a higher Pn/Ps than control genes, the authors argue these results are in line with these genes being under purifying selection but lacking an “island effect”. Instead, the authors argue that demographic effects (i.e., reductions in Ne) may lead to the decreased immunity documented in other studies. In contrast, there was a reduction in Pn/Ps in MHC II genes, known to be under balancing selection. This reduction was stronger in island species and thus the authors argue that this is the only class of genes where a role for relaxed selection can be invoked. Together these results demonstrate that the changes in immunity experienced by island species are complex and that different categories of immune genes can experience different selective pressures. By including control genes in their study, they particularly highlight the importance of accounting for shifts in Ne when examining patterns of island species evolution. Hopefully, this kind of framework will be applied to other taxa to determine if these results are widespread or more specific to birds. References Adler GH, Levins R (1994) The Island Syndrome in Rodent Populations. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1086/418744 Baeckens S, Van Damme R (2020) The island syndrome. Current Biology, 30, R338–R339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029 Barthe M, Doutrelant C, Covas R, Melo M, Illera JC, Tilak M-K, Colombier C, Leroy T, Loiseau C, Nabholz B (2022) Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome. bioRxiv, 2021.11.21.469450, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450 Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Graves GR, Jhala YV, Peirce MA, Rahmani AR, Fonseca DM, Fleischer RC (2006) Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2935–2944. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3671 Burns KC (2019) Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379953 Doutrelant C, Paquet M, Renoult JP, Grégoire A, Crochet P-A, Covas R (2016) Worldwide patterns of bird colouration on islands. Ecology Letters, 19, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12588 Illera JC, Fernández-Álvarez Á, Hernández-Flores CN, Foronda P (2015) Unforeseen biogeographical patterns in a multiple parasite system in Macaronesia. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1858–1870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12548 Lomolino MV (2005) Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01314.x Matson KD (2006) Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 Pérez-Rodríguez A, Ramírez Á, Richardson DS, Pérez-Tris J (2013) Evolution of parasite island syndromes without long-term host population isolation: parasite dynamics in Macaronesian blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 22, 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12084 | Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome | Mathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Shared ecological conditions encountered by species that colonize islands often lead to the evolution of convergent phenotypes, commonly referred to as “island syndrome”. Reduced immune functions have been previousl... |  | Adaptation, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emma Berdan | 2021-11-28 11:01:31 | View | |

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

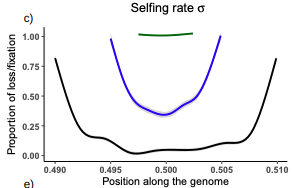

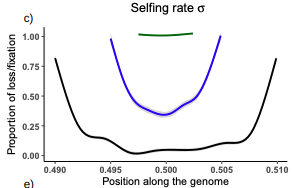

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewerMost mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

18 Nov 2022

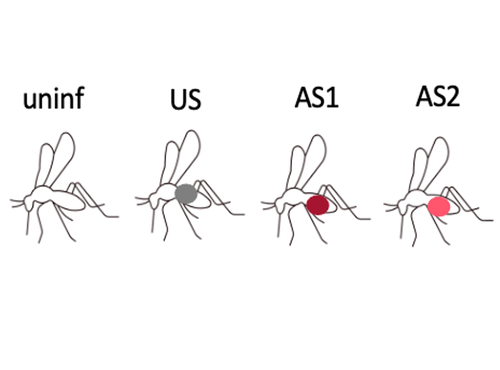

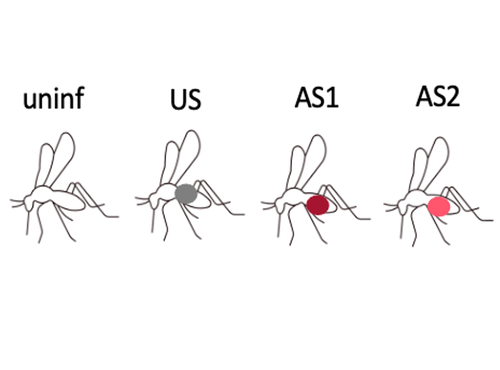

Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in PlasmodiumVilla M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478164The importance of understanding fitness costs associated with drug resistance throughout the life cycle of malaria parasitesRecommended by Silvie Huijben based on reviews by Sarah Reece and Marianna SzucsAntimalarial resistance is a major hurdle to malaria eradication efforts. The spread of drug resistance follows basic evolutionary principles, with competitive interactions between resistant and susceptible malaria strains being central to the fitness of resistant parasites. These competitive interactions can be used to design resistance management strategies, whereby a fitness cost of resistant parasites can be exploited through maintaining competitive suppression of the more fit drug-susceptible parasites. This can potentially be achieved using lower drug dosages or lower frequency of drug treatments. This approach has been demonstrated to work empirically in a rodent malaria model [1,2] and has been demonstrated to have clinical success in cancer treatments [3]. However, these resistance management approaches assume a fitness cost of the resistant pathogen, and, in the case of malaria parasites in general, and for artemisinin resistant parasites in particular, there is limited information on the presence of such fitness cost. The best suggestive evidence for the presence of fitness costs comes from the discontinuation of the use of the drug, which, in the case of chloroquine, was followed by a gradual drop in resistance frequency over the following decade [see e.g. 4,5]. However, with artemisinin derivative drugs still in use, alternative ways to study the presence of fitness costs need to be undertaken. References [1] Huijben S, Bell AS, Sim DG, Tomasello D, Mideo N, Day T, et al. 2013. Aggressive chemotherapy and the selection of drug resistant pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 9(9): e1003578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003578 [5] Mharakurwa S, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Mudare N, Matimba C, Gara TX, Makuwaza A, et al. 2021. Steep rebound of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 223(2): 306-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa368 | Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in Plasmodium | Villa M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drug resistance is a major issue in the control of malaria. Mutations linked to drug resistance often target key metabolic pathways and are therefore expected to be associated with biological costs. The spread of dr... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Life History | Silvie Huijben | 2022-01-31 13:01:16 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer