Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Jul 2020

POSTPRINT

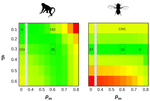

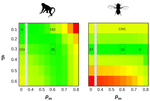

The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in DrosophilaEmily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog https://doi.org/10.1101/156042Y chromosome makes fruit flies die youngerRecommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina VieiraIn most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018). References Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472 | The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View | |

19 Feb 2018

Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY systemAline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/179044Dosage compensation by upregulation of maternal X alleles in both males and females in young plant sex chromosomesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Judith Mank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes evolve as recombination is suppressed between the X and Y chromosomes. The loss of recombination on the sex-limited chromosome (the Y in mammals) leads to degeneration of both gene expression and gene content for many genes [1]. Loss of gene expression or content from the Y chromosome leads to differences in gene dose between males and females for X-linked genes. Because expression levels are often correlated with gene dose [2], these hemizygous genes have a lower expression levels in the heterogametic sex. This in turn disrupts the stoichiometric balance among genes in protein complexes that have components on both the sex chromosomes and autosomes [3], which could have serious deleterious consequences for the heterogametic sex. References | Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY system | Aline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais | <p>During the evolution of sex chromosomes, the Y degenerates and its expression gets reduced relative to the X and autosomes. Various dosage compensation mechanisms that recover ancestral expression levels in males have been described in animals.... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Tatiana Giraud | 2017-09-20 20:39:46 | View | |

06 Apr 2021

How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans?Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030Be careful when studying selection based on polygenic score overdispersionRecommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been a great promise for our understanding of the connection between genotype and phenotype. Today, the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog contains 251,401 associations from 4,961 studies (1). This wealth of studies has also generated interest to use the summary statistics beyond the few top hits in order to make predictions for individuals without known phenotype, e.g. to predict polygenic risk scores or to study polygenic selection by comparing different groups. For instance, polygenic selection acting on the most studied polygenic trait, height, has been subject to multiple studies during the past decade (e.g. 2–6). They detected north-south gradients in Europe which were consistent with expectations. However, their GWAS summary statistics were based on the GIANT consortium data set, a meta-analysis of GWAS conducted in different European cohorts (7,8). The availability of large data sets with less stratification such as the UK Biobank (9) has led to a re-evaluation of those results. The nature of the GIANT consortium data set was realized to represent a potential problem for studies of polygenic adaptation which led several of the authors of the original articles to caution against the interpretations of polygenic selection on height (10,11). This was a great example on how the scientific community assessed their own earlier results in a critical way as more data became available. At the same time it left the question whether there is detectable polygenic selection separating populations more open than ever. Generally, recent years have seen several articles critically assessing the portability of GWAS results and risk score predictions to other populations (12–14). Refoyo-Martínez et al. (15) are now presenting a systematic assessment on the robustness of cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans. They compiled GWAS results for complex traits which have been studied in more than one cohort and then use allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes Project data (16) set to detect signals of polygenic score overdispersion. As the source for the allele frequencies is kept the same across all tests, differences between the signals must be caused by the underlying GWAS. The results are concerning as the level of overdispersion largely depends on the choice of GWAS cohort. Cohorts with homogenous ancestries show little to no overdispersion compared to cohorts of mixed ancestries such as meta-analyses. It appears that the meta-analyses fail to fully account for stratification in their data sets. The authors based most of their analyses on the heavily studied trait height. Additionally, they use educational attainment (measured as the number of school years of an individual) as an example. This choice was due to the potential over- or misinterpretation of results by the media, the general public and by far right hate groups. Such traits are potentially confounded by unaccounted cultural and socio-economic factors. Showing that previous results about polygenic selection on educational attainment are not robust is an important result that needs to be communicated well. This forms a great example for everyone working in human genomics. We need to be aware that our results can sometimes be misinterpreted. And we need to make an effort to write our papers and communicate our results in a way that is honest about the limitations of our research and that prevents the misuse of our results by hate groups. This article represents an important contribution to the field. It is cruicial to be aware of potential methodological biases and technical artifacts. Future studies of polygenic adaptation need to be cautious with their interpretations of polygenic score overdispersion. A recommendation would be to use GWAS results obtained in homogenous cohorts. But even if different biobank-scale cohorts of homogeneous ancestry are employed, there will always be some remaining risk of unaccounted stratification. These conclusions may seem sobering but they are part of the scientific process. We need additional controls and new, different methods than polygenic score overdispersion for assessing polygenic selection. Last year also saw the presentation of a novel approach using sequence data and GWAS summary statistics to detect directional selection on a polygenic trait (17). This new method appears to be robust to bias stemming from stratification in the GWAS cohort as well as other confounding factors. Such new developments show light at the end of the tunnel for the use of GWAS summary statistics in the study of polygenic adaptation. References 1. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1005–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1120 2. Turchin MC, Chiang CW, Palmer CD, Sankararaman S, Reich D, Hirschhorn JN. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs. Nature Genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):1015–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2368 3. Berg JJ, Coop G. A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2014 Aug 7;10(8):e1004412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004412 4. Robinson MR, Hemani G, Medina-Gomez C, Mezzavilla M, Esko T, Shakhbazov K, et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nature Genetics. 2015 Nov;47(11):1357–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3401 5. Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015 Dec;528(7583):499–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152 6. Racimo F, Berg JJ, Pickrell JK. Detecting polygenic adaptation in admixture graphs. Genetics. 2018. Arp;208(4):1565–1584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300489 7. Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7317):832–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09410 8. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014 Nov;46(11):1173–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097 9. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z 10. Berg JJ, Harpak A, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Joergensen AM, Mostafavi H, Field Y, et al. Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39725. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39725 11. Sohail M, Maier RM, Ganna A, Bloemendal A, Martin AR, Turchin MC, et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39702. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39702 12. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics. 2019 Apr;51(4):584–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x 13. Bitarello BD, Mathieson I. Polygenic Scores for Height in Admixed Populations. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):4027–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401658 14. Uricchio LH, Kitano HC, Gusev A, Zaitlen NA. An evolutionary compass for detecting signals of polygenic selection and mutational bias. Evolution Letters. 2019;3(1):69–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.97 15. Refoyo-Martínez A, Liu S, Jørgensen AM, Jin X, Albrechtsen A, Martin AR, Racimo F. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? bioRxiv, 2021, 2020.07.13.200030, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030 16. Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Sep 30;526(7571):68–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 17. Stern AJ, Speidel L, Zaitlen NA, Nielsen R. Disentangling selection on genetically correlated polygenic traits using whole-genome genealogies. bioRxiv. 2020 May 8;2020.05.07.083402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.083402 | How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? | Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo | <p>Over the past decade, summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been used to detect and quantify polygenic adaptation in humans. Several studies have reported signatures of natural selection at sets of SNPs associated... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genetic conflicts, Human Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | 2020-08-14 15:06:54 | View | |

05 Feb 2019

The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the AutosomesGuillaume Achaz, Serge Gangloff, Benoit Arcangioli https://doi.org/10.1101/351288Replication-independent mutations: a universal signature ?Recommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Robert LanfearMutations are the primary source of genetic variation, and there is an obvious interest in characterizing and understanding the processes by which they appear. One particularly important question is the relative abundance, and nature, of replication-dependent and replication-independent mutations - the former arise as cells replicate due to DNA polymerization errors, whereas the latter are unrelated to the cell cycle. A recent experimental study in fission yeast identified a signature of mutations in quiescent (=non-replicating) cells: the spectrum of such mutations is characterized by an enrichment in insertions and deletions (indels) compared to point mutations, and an enrichment of deletions compared to insertions [2]. References [1] Achaz, G., Gangloff, S., and Arcangioli, B. (2019). The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes. BioRxiv, 351288, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/351288 | The quiescent X, the replicative Y and the Autosomes | Guillaume Achaz, Serge Gangloff, Benoit Arcangioli | <p>From the analysis of the mutation spectrum in the 2,504 sequenced human genomes from the 1000 genomes project (phase 3), we show that sexual chromosomes (X and Y) exhibit a different proportion of indel mutations than autosomes (A), ranking the... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Human Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | 2018-07-25 10:37:48 | View | |

20 May 2020

How much does Ne vary among species?Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle https://doi.org/10.1101/861849Further questions on the meaning of effective population sizeRecommended by Martin Lascoux based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIn spite of its name, the effective population size, Ne, has a complex and often distant relationship to census population size, as we usually understand it. In truth, it is primarily an abstract concept aimed at measuring the amount of genetic drift occurring in a population at any given time. The standard way to model random genetic drift in population genetics is the Wright-Fisher model and, with a few exceptions, definitions of the effective population size stems from it: “a certain model has effective population size, Ne, if some characteristic of the model has the same value as the corresponding characteristic for the simple Wright-Fisher model whose actual size is Ne” (Ewens 2004). Since Sewall Wright introduced the concept of effective population size in 1931 (Wright 1931), it has flourished and there are today numerous definitions of it depending on the process being examined (genetic diversity, loss of alleles, efficacy of selection) and the characteristic of the model that is considered. These different definitions of the effective population size were generally introduced to address specific aspects of the evolutionary process. One aspect that has been hotly debated since the first estimates of genetic diversity in natural populations were published is the so-called Lewontin’s paradox (1974). Lewontin noted that the observed variation in heterozygosity across species was much smaller than one would expect from the neutral expectations calculated with the actual size of the species. References Brandvain Y, Wright SI (2016) The Limits of Natural Selection in a Nonequilibrium World. Trends in Genetics, 32, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.004 | How much does Ne vary among species? | Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle | <p>Genetic drift is an important evolutionary force of strength inversely proportional to *Ne*, the effective population size. The impact of drift on genome diversity and evolution is known to vary among species, but quantifying this effect is a d... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Martin Lascoux | 2019-12-08 00:11:00 | View | |

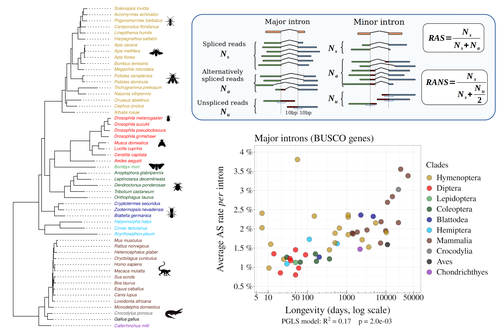

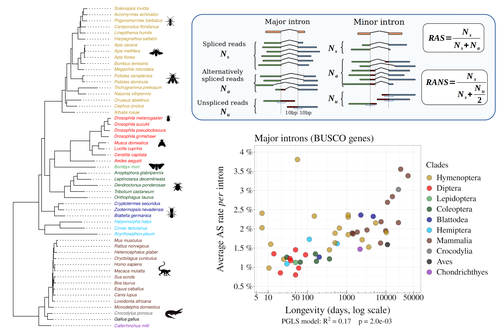

25 Sep 2023

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

22 Sep 2020

Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primatesRylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/445072Studying genetic antagonisms as drivers of genome evolutionRecommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Qi Zhou and 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes are special in the genome because they are often highly differentiated over much of their lengths and marked by degenerative evolution of their gene content. Understanding why sex chromosomes differentiate requires deciphering the forces driving their recombination patterns. Suppression of recombination may be subject to selection, notably because of functional effects of locking together variation at different traits, as well as longer-term consequences of the inefficient purge of deleterious mutations, both of which may contribute to patterns of differentiation [1]. As an example, male and female functions may reveal intrinsic antagonisms over the optimal genotypes at certain genes or certain combinations of interacting genes. As a result, selection may favour the recruitment of rearrangements blocking recombination and maintaining the association of sex-antagonistic allele combinations with the sex-determining locus. References [1] Charlesworth D (2017) Evolution of recombination rates between sex chromosomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160456. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0456 | Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates | Rylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais | <p>Sex chromosomes are typically comprised of a non-recombining region and a recombining pseudoautosomal region. Accurately quantifying the relative size of these regions is critical for sex chromosome biology both from a functional (i.e. number o... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Mathieu Joron | 2019-02-04 15:16:32 | View | |

24 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genomeSébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux 10.1073/pnas.1608979113A newly evolved W(olbachia) sex chromosome in pillbug!Recommended by Gabriel Marais and Sylvain CharlatIn some taxa such as fish and arthropods, closely related species can have different mechanisms of sex determination and in particular different sex chromosomes, which implies that new sex chromosomes are constantly evolving [1]. Several models have been developed to explain this pattern but empirical data are lacking and the causes of the fast sex chromosome turn over remain mysterious [2-4]. Leclerq et al. [5] in a paper that just came out in PNAS have focused on one possible explanation: Wolbachia. This widespread intracellular symbiont of arthropods can manipulate its host reproduction in a number of ways, often by biasing the allocation of resources toward females, the transmitting sex. Perhaps the most spectacular example is seen in pillbugs, where Wolbachia commonly turns infected males into females, thus doubling its effective transmission to grandchildren. Extensive investigations on this phenomenon were initiated 30 years ago in the host species Armadillidium vulgare. The recent paper by Leclerq et al. beautifully validates an hypothesis formulated in these pioneer studies [6], namely, that a nuclear insertion of the Wolbachia genome caused the emergence of new female determining chromosome, that is, a new sex chromosome. Many populations of A. vulgare are infected by the feminising Wolbachia strain wVulC, where the spread of the bacterium has also induced the loss of the ancestral female determining W chromosome (because feminized ZZ individuals produce females without transmitting any W). In these populations, all individuals carry two Z chromosomes, so that the bacterium is effectively the new sex-determining factor: specimens that received Wolbachia from their mother become females, while the occasional loss of Wolbachia from mothers to eggs allows the production of males. Intriguingly, studies from natural populations also report that some females are devoid both of Wolbachia and the ancestral W chromosome, suggesting the existence of new female determining nuclear factor, the hypothetical “f element”. Leclerq et al. [5] found the f element and decrypted its origin. By sequencing the genome of a strain carrying the putative f element, they found that a nearly complete wVulC genome got inserted in the nuclear genome and that the chromosome carrying the insertion has effectively become a new W chromosome. The insertion is indeed found only in females, PCRs and pedigree analysis tell. Although the Wolbachia-derived gene(s) that became sex-determining gene(s) remain to be identified among many possible candidates, the genomic and genetic evidence are clear that this Wolbachia insertion is determining sex in this pillbug strain. Leclerq et al. [5] also found that although this insertion is quite recent, many structural changes (rearrangements, duplications) have occurred compared to the wVulC genome, which study will probably help understand which bacterial gene(s) have retained a function in the nucleus of the pillbug. Also, in the future, it will be interesting to understand how and why exactly the nuclear inserted Wolbachia rose in frequency in the pillbug population and how the cytoplasmic Wolbachia was lost, and to tease apart the roles of selection and drift in this event. We highly recommend this paper, which provides clear evidence that Wolbachia has caused sex chromosome turn over in one species, opening the conjecture that it might have done so in many others. References [1] Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, Hahn MW, Kitano J, Mayrose I, Ming R, Perrin N, Ross L, Valenzuela N, Vamosi JC. 2014. Tree of Sex Consortium. Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS Biology 12: e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899 [2] van Doorn GS, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 449: 909-912. doi: 10.1038/nature06178 [3] Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Grève P. 2011. The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends in Genetics 27: 332-341. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.002 [4] Blaser O, Neuenschwander S, Perrin N. 2014. Sex-chromosome turnovers: the hot-potato model. American Naturalist 183: 140-146. doi: 10.1086/674026 [5] Leclercq S, Thézé J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L, Grève P, Gilbert C, Cordaux R. 2016. Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 113: 15036-15041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608979113 [6] Legrand JJ, Juchault P. 1984. Nouvelles données sur le déterminisme génétique et épigénétique de la monogénie chez le crustacé isopode terrestre Armadillidium vulgare Latr. Génétique Sélection Evolution 16: 57–84. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-16-1-57 | Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome | Sébastien Leclercq, Julien Thézé, Mohamed Amine Chebbi, Isabelle Giraud, Bouziane Moumen, Lise Ernenwein, Pierre Grève, Clément Gilbert, and Richard Cordaux | Sex determination is an evolutionarily ancient, key developmental pathway governing sexual differentiation in animals. Sex determination systems are remarkably variable between species or groups of species, however, and the evolutionary forces und... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Gabriel Marais | 2017-01-13 15:15:51 | View | |

17 May 2021

Relative time constraints improve molecular datingGergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889Dating with constraintsRecommended by Cécile Ané based on reviews by David Duchêne and 1 anonymous reviewerEstimating the absolute age of diversification events is challenging, because molecular sequences provide timing information in units of substitutions, not years. Additionally, the rate of molecular evolution (in substitutions per year) can vary widely across lineages. Accurate dating of speciation events traditionally relies on non-molecular data. For very fast-evolving organisms such as SARS-CoV-2, for which samples are obtained over a time span, the collection times provide this external information from which we can learn the rate of molecular evolution and date past events (Boni et al. 2020). In groups for which the fossil record is abundant, state-of-the-art dating methods use fossil information to complement molecular data, either in the form of a prior distribution on node ages (Nguyen & Ho 2020), or as data modelled with a fossilization process (Heath et al. 2014). Dating is a challenge in groups that lack fossils or other geological evidence, such as very old lineages and microbial lineages. In these groups, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events have been identified as informative about relative dates: the ancestor of the gene's donor must be older than the descendants of the gene's recipient. Previous work using HGTs to date phylogenies have used methodologies that are ad-hoc (Davín et al 2018) or employ a small number of HGTs only (Magnabosco et al. 2018, Wolfe & Fournier 2018). Szöllősi et al. (2021) present and validate a Bayesian approach to estimate the age of diversification events based on relative information on these ages, such as implied by HGTs. This approach is flexible because it is modular: constraints on relative node ages can be combined with absolute age information from fossil data, and with any substitution model of molecular evolution, including complex state-of-art models. To ease the computational burden, the authors also introduce a two-step approach, in which the complexity of estimating branch lengths in substitutions per site is decoupled from the complexity of timing the tree with branch lengths in years, accounting for uncertainty in the first step. Currently, one limitation is that the tree topology needs to be known, and another limitation is that constraints need to be certain. Users of this method should be mindful of the latter when hundreds of constraints are used, as done by Szöllősi et al. (2021) to date the trees of Cyanobacteria and Archaea. Szöllősi et al. (2021)'s method is implemented in RevBayes, a highly modular platform for phylogenetic inference, rapidly growing in popularity (Höhna et al. 2016). The RevBayes tutorial page features a step-by-step tutorial "Dating with Relative Constraints", which makes the method highly approachable. References: Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, Lam TT-Y, Perry BW, Castoe TA, Rambaut A, Robertson DL (2020) Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Microbiology, 5, 1408–1417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4 Davín AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V, Szöllősi GJ (2018) Gene transfers can date the tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0525-3 Heath TA, Huelsenbeck JP, Stadler T (2014) The fossilized birth–death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, E2957–E2966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319091111 Höhna S, Landis MJ, Heath TA, Boussau B, Lartillot N, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2016) RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Systematic Biology, 65, 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw021 Magnabosco C, Moore KR, Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Dating phototrophic microbial lineages with reticulate gene histories. Geobiology, 16, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12273 Nguyen JMT, Ho SYW (2020) Calibrations from the Fossil Record. In: The Molecular Evolutionary Clock: Theory and Practice (ed Ho SYW), pp. 117–133. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60181-2_8 Szollosi, G.J., Hoehna, S., Williams, T.A., Schrempf, D., Daubin, V., Boussau, B. (2021) Relative time constraints improve molecular dating. bioRxiv, 2020.10.17.343889, ver. 8 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889 Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Horizontal gene transfer constrains the timing of methanogen evolution. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0513-7 | Relative time constraints improve molecular dating | Gergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau | <p style="text-align: justify;">Dating the tree of life is central to understanding the evolution of life on Earth. Molecular clocks calibrated with fossils represent the state of the art for inferring the ages of major groups. Yet, other informat... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Cécile Ané | 2020-10-21 23:39:17 | View | |

10 Nov 2017

POSTPRINT

Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of PlacentalsWu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043A new approach to DNA-aided ancestral trait reconstruction in mammalsRecommended by Nicolas Galtier and Belinda ChangReconstructing ancestral character states is an exciting but difficult problem. The fossil record carries a great deal of information, but it is incomplete and not always easy to connect to data from modern species. Alternatively, ancestral states can be estimated by modelling trait evolution across a phylogeny, and fitting to values observed in extant species. This approach, however, is heavily dependent on the underlying assumptions, and typically results in wide confidence intervals. An alternative approach is to gain information on ancestral character states from DNA sequence data. This can be done directly when the trait of interest is known to be determined by a single, or a small number, of major effect genes. In some of these cases it can even be possible to investigate an ancestral trait of interest by inferring and resurrecting ancestral sequences in the laboratory. Examples where this has been successfully used to address evolutionary questions range from the nocturnality of early mammals [1], to the loss of functional uricases in primates, leading to high rates of gout, obesity and hypertension in present day humans [2]. Another possibility is to rely on correlations between species traits and the genome average substitution rate/process. For instance, it is well established that the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rate, dN/dS, is generally higher in large than in small species of mammals, presumably due to a reduced effective population size in the former. By estimating ancestral dN/dS, one can therefore gain information on ancestral body mass (e.g. [3-4]). The interesting paper by Wu et al. [5] further develops this second possibility of incorporating information on rate variation derived from genomic data in the estimation of ancestral traits. The authors analyse a large set of 1185 genes in 89 species of mammals, without any prior information on gene function. The substitution rate is estimated for each gene and each branch of the mammalian tree, and taken as an indicator of the selective constraint applying to a specific gene in a specific lineage – more constraint, slower evolution. Rate variation is modelled as resulting from a gene effect, a branch effect, and a gene X branch interaction effect, which captures lineage-specific peculiarities in the distribution of functional constraint across genes. The interaction term in terminal branches is regressed to observed trait values, and the relationship is used to predict ancestral traits from interaction terms in internal branches. The power and accuracy of the estimates are convincingly assessed via cross validation. Using this method, the authors were also able to use an unbiased approach to determine which genes were the main contributors to the evolution of the life-history traits they reconstructed. The ancestors to current placental mammals are predicted to have been insectivorous - meaning that the estimated distribution of selective constraint across genes in basal branches of the tree resembles that of extant insectivorous taxa - consistent with the mainstream palaeontological hypothesis. Another interesting result is the prediction that only nocturnal lineages have passed the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, so that the ancestors of current orders of placentals would all have been nocturnal. This suggests that the so-called "nocturnal bottleneck hypothesis" should probably be amended. Similar reconstructions are achieved for seasonality, sociality and monogamy – with variable levels of uncertainty. The beauty of the approach is to analyse the variance, not only the mean, of substitution rate across genes, and their methods allow for the identification of the genes contributing to trait evolution without relying on functional annotations. This paper only analyses discrete traits, but the framework can probably be extended to continuous traits as well. References [1] Bickelmann C, Morrow JM, Du J, Schott RK, van Hazel I, Lim S, Müller J, Chang BSW, 2015. The molecular origin and evolution of dim-light vision in mammals. Evolution 69: 2995-3003. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12794 [2] Kratzer, JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN, Cicerchi C, Graves CL, Tipton PA, Ortlund EA, Johnson RJ, Gaucher EA, 2014. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, USA 111:3763-3768. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320393111 [3] Lartillot N, Delsuc F. 2012. Joint reconstruction of divergence times and life-history evolution in placental mammals using a phylogenetic covariance model. Evolution 66:1773-1787. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01558.x [4] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJ, Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:5-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss211 [5] Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. 2016. Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals. Current Biology 27: 3025-3033. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043 | Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals | Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. | Life history and behavioral traits are often difficult to discern from the fossil record, but evolutionary rates of genes and their changes over time can be inferred from extant genomic data. Under the neutral theory, molecular evolutionary rate i... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Nicolas Galtier | 2017-11-10 14:52:26 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer

, where Ne is the effective population size and

, where Ne is the effective population size and  is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common

is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common  . Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.

. Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.