Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

20 Dec 2017

Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiationNicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias 10.1101/148189The influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification, revealed by Neotropical butterfliesRecommended by Richard H Ree based on reviews by Delano Lewis and 1 anonymous reviewerThe influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification is a hot topic in biogeography. Of central interest are questions about where, when, and how fast lineages proliferated, suffered extinction, and migrated in response to tectonic events, the waxing and waning of dominant biomes, etc. In this context, the dynamic conditions of the Miocene have received much attention, from studies of many clades and biogeographic regions. Here, Chazot et al. [1] present an exemplary analysis of butterflies (tribe Ithomiini) in the Neotropics, examining their diversification across the Andes and Amazon. They infer sharp contrasts between these regions in the late Miocene: accelerated diversification during orogeny of the Andes, and greater extinction in the Amazon associated during the Pebas system, with interchange and local diversification increasing following the Pebas during the Pliocene. References [1] Chazot N, Willmott KR, Lamas G, Freitas AVL, Piron-Prunier F, Arias CF, Mallet J, De-Silva DL and Elias M. 2017. Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation. BioRxiv 148189, ver 4 of 19th December 2017. doi: 10.1101/148189 [2] Xing Y, and Ree RH. 2017. Uplift-driven diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a temperate biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114: E3444-E3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616063114 | Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation | Nicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias | The Neotropical region has experienced a dynamic landscape evolution throughout the Miocene, with the large wetland Pebas occupying western Amazonia until 11-8 my ago and continuous uplift of the Andes mountains along the western edge of South Ame... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Richard H Ree | 2017-06-12 11:55:14 | View | |

22 Mar 2022

Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus CorbiculaVastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836Strange reproductive modes and population geneticsRecommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Arnaud Estoup, Simon Henry Martin and 2 anonymous reviewersThere are many organisms that are asexual or have unusual modes of reproduction. One such quasi-sexual reproductive mode is androgenesis, in which the offspring, after fertilization, inherits only the entire paternal nuclear genome. The maternal genome is ditched along the way. One group of organisms which shows this mode of reproduction are clams in the genus Corbicula, some of which are androecious, while others are dioecious and sexual. The study by Vastrade et al. (2022) describes population genetic patterns in these clams, using both nuclear and mitochondrial sequence markers. In contrast to what might be expected for an asexual lineage, there is evidence for significant genetic mixing between populations. In addition, there is high heterozygosity and evidence for polyploidy in some lineages. Overall, the picture is complicated! However, what is clear is that there is far more genetic mixing than expected. One possible mechanism by which this could occur is 'nuclear capture' where there is a mixing of maternal and paternal lineages after fertilization. This can sometimes occur as a result of hybridization between 'species', leading to further mixing of divergent lineages. Thus the group is clearly far from an ancient asexual lineage - recombination and mixing occur with some regularity. The study also analyzed recent invasive populations in Europe and America. These had reduced genetic diversity, but also showed complex patterns of allele sharing suggesting a complex origin of the invasive lineages. In the future, it will be exciting to apply whole genome sequencing approaches to systems such as this. There are challenges in interpreting a handful of sequenced markers especially in a system with polyploidy and considerable complexity, and whole-genome sequencing could clarify some of the outstanding questions, Overall, this paper highlights the complex genetic patterns that can result through unusual reproductive modes, which provides a challenge for the field of population genetics and for the recognition of species boundaries. References Vastrade M, Etoundi E, Bournonville T, Colinet M, Debortoli N, Hedtke SM, Nicolas E, Pigneur L-M, Virgo J, Flot J-F, Marescaux J, Doninck KV (2022) Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. bioRxiv, 590836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836 | Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula | Vastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. | <p style="text-align: justify;">“Occasional” sexuality occurs when a species combines clonal reproduction and genetic mixing. This strategy is predicted to combine the advantages of both asexuality and sexuality, but its actual consequences on the... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Chris Jiggins | 2019-03-29 15:42:56 | View | |

12 Apr 2017

POSTPRINT

Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoesLequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111Vectors as motors (of virus evolution)Recommended by Frédéric Fabre and Benoit MouryMany viruses are transmitted by biological vectors, i.e. organisms that transfer the virus from one host to another. Dengue virus (DENV) is one of them. Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has rapidly spread around the world since the 1940s. One recent estimate indicates 390 million dengue infections per year [1]. As many arthropod-borne vertebrate viruses, DENV has to cross several anatomical barriers in the vector, to multiply in its body and to invade its salivary glands before getting transmissible. As a consequence, vectors are not passive carriers but genuine hosts of the viruses that potentially have important effects on the composition of virus populations and, ultimately, on virus epidemiology and virulence. Within infected vectors, virus populations are expected to acquire new mutations and to undergo genetic drift and selection effects. However, the intensity of these evolutionary forces and the way they shape virus genetic diversity are poorly known. In their study, Lequime et al. [2] finely disentangled the effects of genetic drift and selection on DENV populations during their infectious cycle within mosquito (Aedes aegypti) vectors. They evidenced that the genetic diversity of viruses within their vectors is shaped by genetic drift, selection and vector genotype. The experimental design consisted in artificial acquisition of purified virus by mosquitoes during a blood meal. The authors monitored the diversity of DENV populations in Ae. aegypti individuals at different time points by high-throughput sequencing (HTS). They estimated the intensity of genetic drift and selection effects exerted on virus populations by comparing the DENV diversity at these sampling time points with the diversity in the purified virus stock (inoculum). Disentangling the effects of genetic drift and selection remains a methodological challenge because both evolutionary forces operate concomitantly and both reduce genetic diversity. However, selection reduces diversity in a reproducible manner among experimental replicates (here, mosquito individuals): the fittest variants are favoured at the expense of the weakest ones. In contrast, genetic drift reduces diversity in a stochastic manner among replicates. Genetic drift acts equally on all variants irrespectively of their fitness. The strength of genetic drift is frequently evaluated with the effective population size Ne: the lower Ne, the stronger the genetic drift [3]. The estimation of the effective population size of DENV populations by Lequime et al. [2] was based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were (i) present both in the inoculum and in the virus populations sampled at the different time points and (ii) that were neutral (or nearly-neutral) and therefore subjected to genetic drift only and insensitive to selection. As expected for viruses that possess small and constrained genomes, such neutral SNPs are extremely rare. Starting from a set of >1800 SNPs across the DENV genome, only three SNPs complied with the neutrality criteria and were enough represented in the sequence dataset for a precise Ne estimation. Using the method described by Monsion et al. [4], Lequime et al. [2] estimated Ne values ranging from 5 to 42 viral genomes (95% confidence intervals ranged from 2 to 161 founding viral genomes). Consequently, narrow bottlenecks occurred at the virus acquisition step, since the blood meal had allowed the ingestion of ca. 3000 infectious virus particles, on average. Interestingly, bottleneck sizes did not differ between mosquito genotypes. Monsion et al.’s [4] formula provides only an approximation of Ne. A corrected formula has been recently published [5]. We applied this exact Ne formula to the means and variances of the frequencies of the three neutral markers estimated before and after the bottlenecks (Table 1 in [2]), and nearly identical Ne estimates were obtained with both formulas. Selection intensity was estimated from the dN/dS ratio between the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution rates using the HTS data on DENV populations. DENV genetic diversity increased following initial infection but was restricted by strong purifying selection during virus expansion in the midgut. Again, no differences were detected between mosquito genotypes. However and importantly, significant differences in DENV genetic diversity were detected among mosquito genotypes. As they could not be related to differences in initial genetic drift or to selection intensity, the authors raise interesting alternative hypotheses, including varying rates of de novo mutations due to differences in replicase fidelity or differences in the balancing selection regime. Interestingly, they also suggest that this observation could simply result from a methodological issue linked to the detection threshold of low-frequency SNPs. References [1] Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496: 504–7 doi: 10.1038/nature12060 [2] Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L. 2016. Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes. PloS Genetics 12: e1006111 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111 [3] Charlesworth B. 2009. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature Reviews Genetics 10: 195-205 doi: 10.1038/nrg2526 [4] Monsion B, Froissart R, Michalakis Y and Blanc S. 2008. Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization. PloS Pathogens 4: e1000174 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000174 [5] Thébaud G and Michalakis Y. 2016. Comment on ‘Large bottleneck size in cauliflower mosaic virus populations during host plant colonization’ by Monsion et al. (2008). PloS Pathogens 12: e1005512 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005512 | Genetic drift, purifying selection and vector genotype shape dengue virus intra-host genetic diversity in mosquitoes | Lequime S, Fontaine A, Gouilh MA, Moltini-Conclois I and Lambrechts L | Due to their error-prone replication, RNA viruses typically exist as a diverse population of closely related genomes, which is considered critical for their fitness and adaptive potential. Intra-host demographic fluctuations that stochastically re... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Frédéric Fabre | 2017-04-10 14:26:04 | View | |

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View | |

03 Apr 2017

Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous EnvironmentsRomain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/100743Experimental test of the conditions of maintenance of polymorphism under hard and soft selectionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Joachim Hermisson and 2 anonymous reviewers

Theoretical work, initiated by Levene (1953) [1] and Dempster (1955) [2], suggests that within a given environment, the way populations are regulated and contribute to the next generation is a key factor for the maintenance of local adaptation polymorphism. In this theoretical context, hard selection describes the situation where the genetic composition of each population affects its contribution to the next generation whereas soft selection describes the case where the contribution of each population is fixed, whatever its genetic composition. Soft selection is able to maintain polymorphism, whereas hard selection invariably leads to the fixation of one of the alleles. Although the specific conditions (e.g. of migration between populations or drift level) in which this prediction holds have been studied in details by theoreticians, experimental tests have mainly failed, usually leading to the conclusion that the allele frequency dynamics was driven by other mechanisms in the experimental systems and conditions used. Gallet, Froissart and Ravigné [3] have set up a bacterial experimental system which allowed them to convincingly demonstrate that soft selection generates the conditions for polymorphism maintenance when hard selection does not, everything else being equal. The key ingredients of their experimental system are (1) the possibility to accurately produce hard and soft selection regimes when daily transferring the populations and (2) the ability to establish artificial well-characterized reproducible trade-offs. To do so, they used two genotypes resisting each one to one antibiotic and combined, across habitats, low antibiotic doses and difference in medium productivity. The experimental approach contains two complementary parts: the first one is looking at changes in the frequencies of two genotypes, initially introduced at around 50% each, over a small number of generations (ca 40) in different environments and selection regimes (soft/hard) and the second one is convincingly showing polymorphism protection by establishing that in soft selection regimes, the lowest fitness genotype is not eliminated even when introduced at low frequency. In this manuscript, a key point is the dialog between theoretical and experimental approaches. The experiments have been thought and designed to be as close as possible to the situations analysed in theoretical work. For example, the experimental polymorphism protection test (experiment 2) closely matches the equivalent analysis classically performed in theoretical approaches. This close fit between theory and experiment is clearly a strength of this study. This said, the experimental system allowing them to realise this close match also has some limitations. For example, changes in allele frequencies could only be monitored over a quite low number of generations because a longer time-scale would have allowed the contribution of de novo mutations and the likely emergence of a generalist genotype resisting to both antibiotics used to generate the local adaptation trade-offs. These limitations, as well as the actual significance of the experimental tests, are discussed in deep details in the manuscript. References [1] Levene H. 1953. Genetic equilibrium when more than one niche is available. American Naturalist 87: 331–333. doi: 10.1086/281792 [2] Dempster ER. 1955. Maintenance of genetic heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 20: 25–32. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1955.020.01.005 [3] Gallet R, Froissart R, Ravigné V. 2017. Things softly attained are long retained: dissecting the impacts of selection regimes on polymorphism maintenance in experimental spatially heterogeneous environments. bioRxiv 100743; doi: 10.1101/100743 | Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous Environments | Romain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné | <p>Predicting and managing contemporary adaption requires a proper understanding of the determinants of genetic variation. Spatial heterogeneity of the environment may stably maintain polymorphism when habitat contribution to the next generation c... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-01-17 11:06:21 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

16 Nov 2022

Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in miceCarole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634Tinder in mice: A match made with the sense of smellRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer

Differentiation-based genome scans lie at the core of speciation and adaptation genomics research. Dating back to Lewontin & Krakauer (1973), they have become very popular with the advent of genomics to identify genome regions of enhanced differentiation relative to neutral expectations. These regions may represent genetic barriers between divergent lineages and are key for studying reproductive isolation. However, genome scan methods can generate a high rate of false positives, primarily if the neutral population structure is not accounted for (Bierne et al. 2013). Moreover, interpreting genome scans can be challenging in the context of secondary contacts between diverging lineages (Bierne et al. 2011), because the coupling between different components of reproductive isolation (local adaptation, intrinsic incompatibilities, mating preferences, etc.) can occur readily, thus preventing the causes of differentiation from being determined. Smadja and collaborators (2022) applied a sophisticated genome scan for trait association (BAYPASS, Gautier 2015) to underlie the genetic basis of a polygenetic behaviour: assortative mating in hybridizing mice. My interest in this neat study mainly relies on two reasons. First, the authors used an ingenious geographical setting (replicate pairs of “Choosy” versus “Non-Choosy” populations) with multi-way comparisons to narrow down the list of candidate regions resulting from BAYPASS. The latter corrects for population structure, handles cost-effective pool-seq data and allows for gene-based analyses that aggregate SNP signals within a gene. These features reinforce the set of outlier genes detected; however, not all are expected to be associated with mating preference. The second reason why this study is valuable to me is that Smadja et al. (2022) complemented the population genomic approach with functional predictions to validate the genetic signal. In line with previous behavioural and chemical assays on the proximal mechanisms of mating preferences, they identified multiple olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes as highly significant candidates. Therefore, combining genomic signals with functional analyses is a clever way to provide insights into the causes of reproductive isolation, especially when multiple barriers are involved. This is typically true for reinforcement (Butlin & Smadja 2018), suspected to occur in these mice because, in that case, assortative mating (a prezygotic barrier) evolves in response to the cost of hybridization (for example, due to hybrid inviability). As advocated by the authors, their study paves the way for future work addressing the genetic basis of reinforcement, a trait of major evolutionary importance for which we lack empirical data. They also make a compelling case using complementary approaches that olfactory and vomeronasal receptors have a central role in mammal speciation.

Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P (2011) The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol Ecol 20: 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x Bierne N, Roze D, Welch JJ (2013) Pervasive selection or is it…? why are FST outliers sometimes so frequent? Mol Ecol 22: 2061–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12241 Butlin RK, Smadja CM (2018) Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. Am Nat 191:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/695136 Gautier M (2015) Genome-Wide Scan for Adaptive Divergence and Association with Population-Specific Covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.181453 Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/74.1.175 Smadja CM, Loire E, Caminade P, Severac D, Gautier M, Ganem G (2022) Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice. bioRxiv, 2022.07.21.500634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634 | Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice | Carole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem | <p>Deciphering the genetic bases of behavioural traits is essential to understanding how they evolve and contribute to adaptation and biological diversification, but it remains a substantial challenge, especially for behavioural traits with polyge... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Speciation | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-07-25 11:54:52 | View | |

25 Feb 2021

Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwigSophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363Assessing the role of host-symbiont interactions in maternal care behaviourRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

The role of microbial symbionts in governing social traits of their hosts is an exciting and developing research area. Just like symbionts influence host reproductive behaviour and can cause mating incompatibilities to promote symbiont transmission through host populations (Engelstadter and Hurst 2009; Correa and Ballard 2016; Johnson and Foster 2018) (see also discussion on conflict resolution in Johnsen and Foster 2018), microbial symbionts could enhance transmission by promoting the social behaviour of their hosts (Ezenwa et al. 2012; Lewin-Epstein et al. 2017; Gurevich et al. 2020). Here I apply the term ‘symbiosis’ in the broad sense, following De Bary 1879 as “the living together of two differently named organisms“ independent of effects on the organisms involved (De Bary 1879), i.e. the biological interaction between the host and its symbionts may include mutualism, parasitism and commensalism. References Correa, C. C., and Ballard, J. W. O. (2016). Wolbachia associations with insects: winning or losing against a master manipulator. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 153. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00153 De Bary, A. (1879). Die Erscheinung der Symbiose. Verlag von Karl J. Trubner, Strassburg. Engelstädter, J., and Hurst, G. D. (2009). The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 127-149. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120206 Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M., and Xavier, J. B. (2012). Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science, 338(6104), 198-199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412 Gurevich, Y., Lewin-Epstein, O., and Hadany, L. (2020). The evolution of paternal care: a role for microbes?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1808), 20190599. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0599 Hird, S. M. (2017). Evolutionary biology needs wild microbiomes. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 725. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00725 Johnson, K. V. A., and Foster, K. R. (2018). Why does the microbiome affect behaviour?. Nature reviews microbiology, 16(10), 647-655. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3 Kramer et al. (2017). When earwig mothers do not care to share: parent–offspring competition and the evolution of family life. Functional Ecology, 31(11), 2098-2107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12915 Lewin-Epstein, O., Aharonov, R., and Hadany, L. (2017). Microbes can help explain the evolution of host altruism. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14040 Meunier, J., and Kölliker, M. (2012). Parental antagonism and parent–offspring co-adaptation interact to shape family life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1744), 3981-3988. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1416 Meunier, J., Wong, J. W., Gómez, Y., Kuttler, S., Röllin, L., Stucki, D., and Kölliker, M. (2012). One clutch or two clutches? Fitness correlates of coexisting alternative female life-histories in the European earwig. Evolutionary Ecology, 26(3), 669-682. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9510-x Nalepa, C. A. (2020). Origin of mutualism between termites and flagellated gut protists: transition from horizontal to vertical transmission. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00014 Ratz, T., Kramer, J., Veuille, M., and Meunier, J. (2016). The population determines whether and how life-history traits vary between reproductive events in an insect with maternal care. Oecologia, 182(2), 443-452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3685-3 Van Meyel, S., Devers, S., Dupont, S., Dedeine, F. and Meunier, J. (2021) Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig. bioRxiv, 2020.10.08.331363. ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363 | Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig | Sophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier | <p>The microbes residing within the gut of an animal host often increase their own fitness by modifying their host’s physiological, reproductive, and behavioural functions. Whereas recent studies suggest that they may also shape host sociality and... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2020-10-09 14:07:47 | View | |

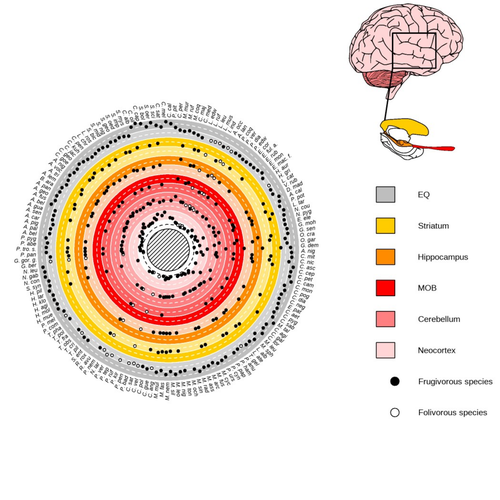

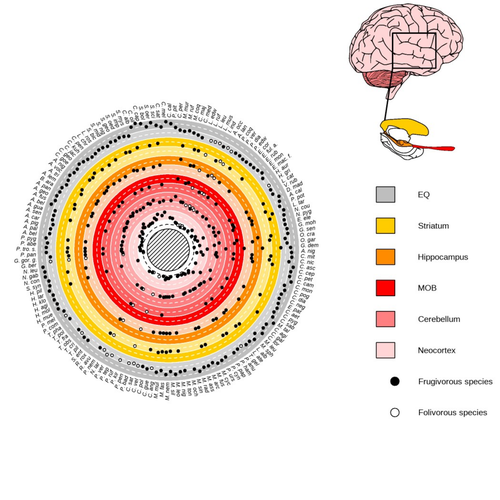

28 Feb 2023

Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architectureBenjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912Macroevolutionary drivers of brain evolution in primatesRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Paula Gonzalez, Orlin Todorov and 3 anonymous reviewersStudying the evolution of animal cognition is challenging because many environmental and species-related factors can be intertwined, which is further complicated when looking at deep-time evolution. Previous knowledge has emphasized the role of intraspecific interactions in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. However, much less is known about such an effect at the interspecific level. Yet, the coexistence of different species in the same geographic area at a given time (sympatry) can impact the evolutionary history of species through character displacement due to biotic interactions. Trait evolution has been observed and tested with morphological external traits but more rarely with brain evolution. Compared to most species’ traits, brain evolution is even more delicate to assess since specific brain regions can be involved in different functions, may they be individual-based and social-based information processing. In a very original and thoroughly executed study, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) addressed the question: How does the co-occurrence of congeneric species shape brain evolution and influence species diversification? By considering brain size as a proxy for cognition, they evaluated whether species sympatry impacted the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates. Fruit resources are hard to find, not continuous through time, heterogeneously distributed across space, but can be predictable. Hence, cognition considerably shapes the foraging strategy and competition for food access can be fierce. Over long timescales, it remains unclear whether brain size and the pace of species diversification are linked in the context of sympatry, and if so how. Recent studies have found that larger brain sizes can be associated with higher diversification rates in birds (Sayol et al. 2019). Similarly, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) thus wondered if the evolution of brain size in primates impacted their dynamic of species diversification, which has been suggested (Melchionna et al. 2020) but not tested. Prior to anything, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) had to retrace the evolutionary history of sympatry between frugivorous primate lineages through time using the primate tree of life, species’ extant distribution, and process-based models to estimate ancestral range evolution. To infer the effect of species sympatry on the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates, the authors evaluated the support for phylogenetic models of brain size evolution accounting or not for species sympatry and investigated the directionality of the selection induced by sympatry on brain size evolution. Finally, to better understand the impact of cognition and interactions between primates on their evolutionary success, they tested for correlations between brain size or species’ sympatry and species diversification. Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) found that the evolution of the whole brain or brain regions used in immediate information processing was best fitted with models not considering sympatry. By contrast, models considering species sympatry best predicted the evolution of brain regions related to long-term memory of interactions with the socio-ecological environment, with a decrease in their size along with stronger sympatry. Specifically, they found that sympatry was associated with a decrease in the relative size of the hippocampus and striatum, but had no significant effect on the neocortex, cerebellum, or overall brain size. The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a crucial role in processing and memorizing spatiotemporal information, which is relevant for frugivorous primates in their foraging behavior. The study suggests that competition between sympatric species for limited food resources may lead to a more complex and unpredictable food distribution, which may in turn render cognitive foraging not advantageous and result in a selection for smaller brain regions involved in foraging. Niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry may also impact cognitive abilities, with more specialized diets requiring lower cognitive abilities and smaller brain region sizes. On the other hand, the absence of an effect of sympatry on brain regions involved in immediate sensory information processing, such as the cerebellum and neocortex, suggests that foragers do not exploit cues left out by sympatric heterospecific species, or they may discard environmental cues in favor of social cues. This is a remarkable study that highlights the importance of considering the impact of ecological factors, such as sympatry, on the evolution of specific brain regions involved in cognitive processes, and the potential trade-offs in brain region size due to niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms behind these effects and to test for the possible role of social cues in the evolution of brain regions. This study provides insights into the selective pressures that shape brain evolution in primates. References Melchionna M, Mondanaro A, Serio C, Castiglione S, Di Febbraro M, Rook L, Diniz-Filho JAF, Manzi G, Profico A, Sansalone G, Raia P (2020) Macroevolutionary trends of brain mass in Primates. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz161 Robira B, Perez-Lamarque B (2023) Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture. bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.490912, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912 Sayol F, Lapiedra O, Ducatez S, Sol D (2019) Larger brains spur species diversification in birds. Evolution, 73, 2085–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13811 | Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture | Benjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque | <p style="text-align: justify;">The main hypotheses on the evolution of animal cognition emphasise the role of conspecifics in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. Yet, space is often simultaneously occupied by multiple sp... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2022-05-10 13:43:02 | View | |

21 Nov 2019

Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticityRobin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous https://doi.org/10.1101/717702Nutrition-dependent effects of gut bacteria on growth plasticity in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well known that the rearing environment has strong effects on life history and fitness traits of organisms. Microbes are part of every environment and as such likely contribute to such environmental effects. Gut bacteria are a special type of microbe that most animals harbor, and as such they are part of most animals’ environment. Such microbial symbionts therefore likely contribute to local adaptation [1]. The main question underlying the laboratory study by Guilhot et al. [2] was: How much do particular gut bacteria affect the organismal phenotype, in terms of life history and larval foraging traits, of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common laboratory model species in biology? References [1] Kawecki, T. J. and Ebert, D. (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7: 1225-1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x | Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticity | Robin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous | <p>Environmentally acquired microbial symbionts could contribute to host adaptation to local conditions like vertically transmitted symbionts do. This scenario necessitates symbionts to have different effects in different environments. We investig... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity, Species interactions | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2019-02-13 15:22:23 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer