Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

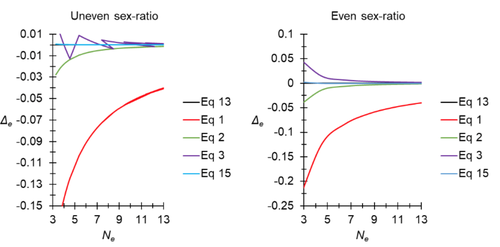

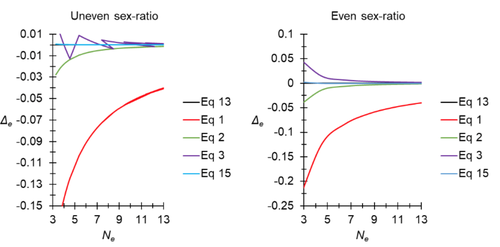

16 May 2023

A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofsThierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968All you ever wanted to know about Ne in one handy placeRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by Jesse ("Jay") Taylor and 1 anonymous reviewerOf the four evolutionary forces, three can be straightforwardly summarized both conceptually and mathematically in the context of an allele at a genomic locus. Mutation (the mutation rate, μ) is simply captured by the per-site, per-generation probability that an allele mutates into a different allele. Recombination (the recombination rate, r) is captured as the probability of recombination between two sites, wherein alleles that are in different genomes in one generation come together in the same genome in the next generation. Natural selection (the selection coefficient, s) is captured by the probability that an allele is present in the next generation, relative to some reference. Random genetic drift – the random fluctuation in allele frequency due to sampling in a finite population - is not so straightforwardly summarized. The first, and most common way of characterizing evolutionary dynamics in a finite population is the Wright-Fisher model, in which the only deviation from the assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg conditions is finite population size. Importantly, in a W-F population, mating between diploid individuals is random, which implies self-fertile monoecy, and generations are non-overlapping. In an ideal W-F population, the probability that a gene copy leaves i descendants in the next generation is the result of binomial sampling of uniting gametes (if the locus is biallelic). The – and the next word is meaningful – magnitude/strength/rate/power/amount of genetic drift is proportional to 1/2N, where N is the size of the population. All of the following are affected by genetic drift: (1) the probability that a neutral allele ultimately reaches fixation, (2) the rate of loss of genetic variation within a population, (3) the rate of increase of genetic variance among populations, (4) the amount of genetic variation segregating in a population, (5) the probability of fixation/loss of a weakly selected variant. Presumably no real population adheres to ideal W-F conditions, which leads to the notion of "effective population size", Ne (Wright 1931), loosely defined as "the size of an ideal W-F population that experiences an equivalent strength of genetic drift". Almost always, Ne<N, and any violation of W-F assumptions can affect Ne. Importantly, Ne can be defined in different ways, and the specific formulation of Ne can have different implications for evolution. Ne was initially defined in terms of the rate of decrease of heterozygosity (inbreeding effective size) and increase in variance among populations (variance effective size). Ewens (1979) defined the Eigenvalue effective size (equivalent to the "random extinction" effective size) and elaborated on the conditions under which the various formulations of Ne differ (Ewens 1982). Nordborg and Krone (2002) defined the effective size in terms of the coalescent, and they identified conditions in which genetic drift cannot be described in terms of a W-F model (Sjodin et al. 2005); also see Karasov et al. (2010); Neher and Shraiman (2011). Distinct from the issue of defining Ne is the issue of calculating Ne from data, which is the focus of this paper by De Meeus and Noûs (2023). Pudovkin et al. (1996) showed that the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population can be formulated in terms of excess heterozygosity, which the current authors note is equivalent to formulating Ne in terms of Wright's FIS statistic. As emphasized by the title, the marquee contribution of this paper is to provide a better approximation of the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population. Science marches onward, although the empirical utility of this advance is obviously limited, given the tremendous inherent sources of uncertainty in real-world estimates of Ne. Perhaps more valuable, however, is the extensive set of appendixes, in which detailed derivations are provided for the various formulations of effective size. By way of analogy, the material presented here can be thought of as an extension of the material presented in section 7.6 of Crow and Kimura (1970), in which the Inbreeding and Variance effective population sizes are derived and compared. The appendixes should serve as a handy go-to source of detailed theoretical information with respect to the different formulations of effective population size. REFERENCES Crow, J. F. and M. Kimura. 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ. De Meeûs, T. and Noûs, C. 2023. A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs. Zenodo, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968 Ewens, W. J. 1979. Mathematical Population Genetics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Ewens, W. J. 1982. On the concept of the effective population size. Theoretical Population Biology 21:373-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(82)90024-7 Karasov, T., P. W. Messer, and D. A. Petrov. 2010. Evidence that adaptation in Drosophila Is not limited by mutation at single sites. Plos Genetics 6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000924 Neher, R. A. and B. I. Shraiman. 2011. Genetic Draft and Quasi-Neutrality in Large Facultatively Sexual Populations. Genetics 188:975-U370. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.111.128876 Nordborg, M. and S. M. Krone. 2002. Separation of time scales and convergence to the coalescent in structured populations. Pp. 194–232 in M. Slatkin, and M. Veuille, eds. Modern Developments in Theoretical Population Genetics: The Legacy of Gustave Malécot. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~krone/malecot.pdf Pudovkin, A. I., D. V. Zaykin, and D. Hedgecock. 1996. On the potential for estimating the effective number of breeders from heterozygote-excess in progeny. Genetics 144:383-387. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/144.1.383 Sjodin, P., I. Kaj, S. Krone, M. Lascoux, and M. Nordborg. 2005. On the meaning and existence of an effective population size. Genetics 169:1061-1070. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.026799 Wright, S. 1931. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16:0097-0159. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/16.2.97 | A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs | Thierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs | <p>The effective population size is an important concept in population genetics. It corresponds to a measure of the speed at which genetic drift affects a given population. Moreover, this is most of the time the only kind of population size that e... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Charles Baer | 2023-02-22 16:53:49 | View | |

10 Nov 2017

POSTPRINT

Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of PlacentalsWu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043A new approach to DNA-aided ancestral trait reconstruction in mammalsRecommended by Nicolas Galtier and Belinda ChangReconstructing ancestral character states is an exciting but difficult problem. The fossil record carries a great deal of information, but it is incomplete and not always easy to connect to data from modern species. Alternatively, ancestral states can be estimated by modelling trait evolution across a phylogeny, and fitting to values observed in extant species. This approach, however, is heavily dependent on the underlying assumptions, and typically results in wide confidence intervals. An alternative approach is to gain information on ancestral character states from DNA sequence data. This can be done directly when the trait of interest is known to be determined by a single, or a small number, of major effect genes. In some of these cases it can even be possible to investigate an ancestral trait of interest by inferring and resurrecting ancestral sequences in the laboratory. Examples where this has been successfully used to address evolutionary questions range from the nocturnality of early mammals [1], to the loss of functional uricases in primates, leading to high rates of gout, obesity and hypertension in present day humans [2]. Another possibility is to rely on correlations between species traits and the genome average substitution rate/process. For instance, it is well established that the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rate, dN/dS, is generally higher in large than in small species of mammals, presumably due to a reduced effective population size in the former. By estimating ancestral dN/dS, one can therefore gain information on ancestral body mass (e.g. [3-4]). The interesting paper by Wu et al. [5] further develops this second possibility of incorporating information on rate variation derived from genomic data in the estimation of ancestral traits. The authors analyse a large set of 1185 genes in 89 species of mammals, without any prior information on gene function. The substitution rate is estimated for each gene and each branch of the mammalian tree, and taken as an indicator of the selective constraint applying to a specific gene in a specific lineage – more constraint, slower evolution. Rate variation is modelled as resulting from a gene effect, a branch effect, and a gene X branch interaction effect, which captures lineage-specific peculiarities in the distribution of functional constraint across genes. The interaction term in terminal branches is regressed to observed trait values, and the relationship is used to predict ancestral traits from interaction terms in internal branches. The power and accuracy of the estimates are convincingly assessed via cross validation. Using this method, the authors were also able to use an unbiased approach to determine which genes were the main contributors to the evolution of the life-history traits they reconstructed. The ancestors to current placental mammals are predicted to have been insectivorous - meaning that the estimated distribution of selective constraint across genes in basal branches of the tree resembles that of extant insectivorous taxa - consistent with the mainstream palaeontological hypothesis. Another interesting result is the prediction that only nocturnal lineages have passed the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, so that the ancestors of current orders of placentals would all have been nocturnal. This suggests that the so-called "nocturnal bottleneck hypothesis" should probably be amended. Similar reconstructions are achieved for seasonality, sociality and monogamy – with variable levels of uncertainty. The beauty of the approach is to analyse the variance, not only the mean, of substitution rate across genes, and their methods allow for the identification of the genes contributing to trait evolution without relying on functional annotations. This paper only analyses discrete traits, but the framework can probably be extended to continuous traits as well. References [1] Bickelmann C, Morrow JM, Du J, Schott RK, van Hazel I, Lim S, Müller J, Chang BSW, 2015. The molecular origin and evolution of dim-light vision in mammals. Evolution 69: 2995-3003. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12794 [2] Kratzer, JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN, Cicerchi C, Graves CL, Tipton PA, Ortlund EA, Johnson RJ, Gaucher EA, 2014. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, USA 111:3763-3768. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320393111 [3] Lartillot N, Delsuc F. 2012. Joint reconstruction of divergence times and life-history evolution in placental mammals using a phylogenetic covariance model. Evolution 66:1773-1787. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01558.x [4] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJ, Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:5-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss211 [5] Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. 2016. Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals. Current Biology 27: 3025-3033. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043 | Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals | Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. | Life history and behavioral traits are often difficult to discern from the fossil record, but evolutionary rates of genes and their changes over time can be inferred from extant genomic data. Under the neutral theory, molecular evolutionary rate i... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Nicolas Galtier | 2017-11-10 14:52:26 | View | |

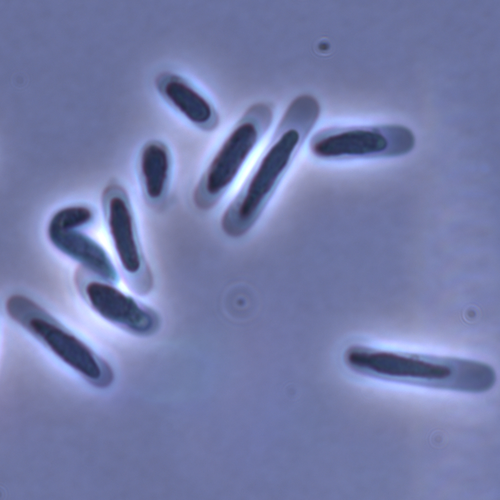

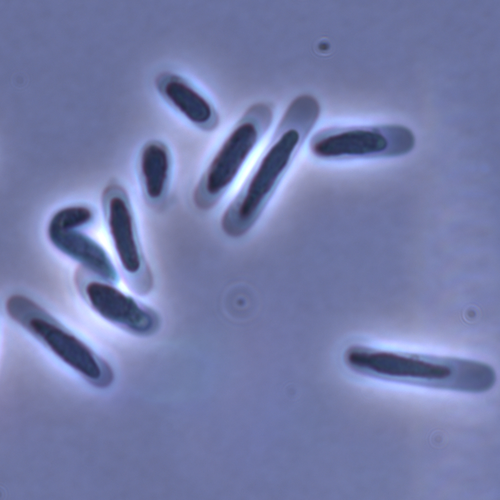

06 Oct 2022

Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch.Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic contextRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia. Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009). This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value. References Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15 Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414 Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5 Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108 Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536 | Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View | |

24 Mar 2023

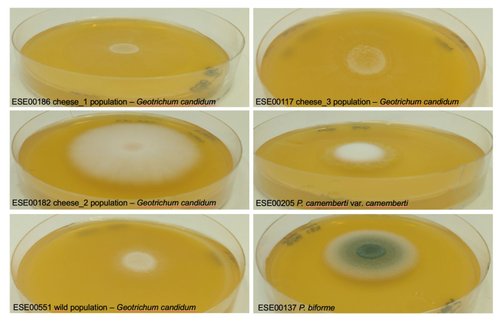

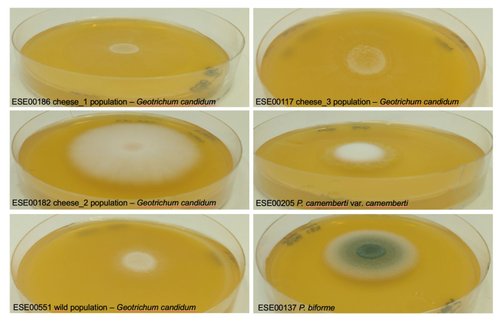

Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidumBastien Bennetot, Jean-Philippe Vernadet, Vincent Perkins, Sophie Hautefeuille, Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega, Samuel O’Donnell, Alodie Snirc, Cécile Grondin, Marie-Hélène Lessard, Anne-Claire Peron, Steve Labrie, Sophie Landaud, Tatiana Giraud, Jeanne Ropars https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.17.492043Diverse outcomes in cheese fungi domesticationRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Delphine Sicard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Delphine Sicard and 1 anonymous reviewer

Domestication is a complex process that imprints the demography and the genomes of domesticated populations, enforcing strong selective pressures on traits favourable to humans, e.g. for food production [1]. Domestication has been quite intensely studied in plants and animals, but less so in micro-organisms such as fungi, despite their assets (e.g. their small genomes and tractability in the lab). This elegant study by Bennetot and collaborators [2] on the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum adds to the mounting body of studies in the genomics of fungi, proving they are excellent models in evolutionary biology for studying adaptation and drift in eukaryotes [3]. Bennetot et al. newly showed with whole genome sequences that all G. candidum strains isolated from cheese form a monophyletic clade subdivided into three genetically differentiated populations with several admixed strains, while the wild strains sampled from diverse geographic locations form a sister clade. This suggests the wild progenitor was not sampled in the present study and calls for future exciting work on the domestication history of the G. candidum fungus. The authors scanned the genomes for footprints of adaptation to the cheese environment and identified promising candidates, such as a gene involved in iron uptake (this element is limiting in cheese). Their functional genome analysis also provides evidence for higher contents of transposable elements in cheese-making strains, likely due to relaxed selection during the domestication process. This paper is particularly impressive in that the authors complemented the population genomic approach with the phenotypic characterization of the strains and tested their ability to outcompete common fungal food spoilers. The authors convincingly showed that cheese-making strains display phenotypic differences relative to wild relatives for multiple traits such as slower growth, lower proteolysis activity and a greater amount of volatiles attractive to consumers, these phenotypes being beneficial for cheese making. Finally, this work is particularly inspiring because it thoroughly discusses convergent evolution during domestication in different cheese-associated fungi. Indeed, studying populations experiencing similar environmental pressures is fundamental to understanding whether evolution is repeatable [4]. For instance, all three cheese populations of G. candidum exhibit a lower genetic diversity than wild populations. However, only one population displays a stronger domestication syndrome, resembling the Penicillium camemberti situation [5]. Furthermore, different cheese-making practices may have led to varying situations with clonal lineages in non-Roquefort P. roqueforti and P. camemberti [5, 6], while the cheese-making G. candidum populations still harbour some diversity. In a nutshell, Bennetot's study makes an important contribution to evolutionary biology and highlights the value of diversifying our model organisms toward under-represented clades. REFERENCES [1] Diamond J (2002) Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418: 700–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01019 [2] Bennetot B, Vernadet J-P, Perkins V, Hautefeuille S, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, O’Donnell S, Snirc A, Grondin C, Lessard M-H, Peron A-C, Labrie S, Landaud S, Giraud T, Ropars J (2023) Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus Geotrichum candidum. bioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492043, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.17.492043 [3] Gladieux P, Ropars J, Badouin H, Branca A, Aguileta G, de Vienne DM, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Branco S, Giraud T (2014) Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Mol. Ecol. 23: 753–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12631 [4] Bolnick DI, Barrett RD, Oke KB, Rennison DJ, Stuart YE (2018) (Non)Parallel evolution. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49: 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062240 [5] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biol. 30: 4441–4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [6] Dumas, E, Feurtey, A, Rodríguez de la Vega, RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Mol Ecol. 29: 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 | Domestication of different varieties in the cheese-making fungus *Geotrichum candidum* | Bastien Bennetot, Jean-Philippe Vernadet, Vincent Perkins, Sophie Hautefeuille, Ricardo C. Rodríguez de la Vega, Samuel O’Donnell, Alodie Snirc, Cécile Grondin, Marie-Hélène Lessard, Anne-Claire Peron, Steve Labrie, Sophie Landaud, Tatiana Giraud,... | <p>Domestication is an excellent model for studying adaptation processes, involving recent adaptation and diversification, convergence following adaptation to similar conditions, as well as degeneration of unused functions. <em>Geotrichum candidum... |  | Adaptation, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-08-12 20:50:42 | View | |

23 Feb 2024

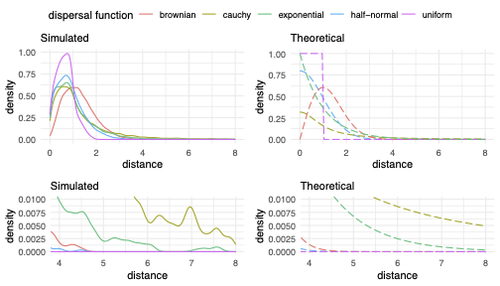

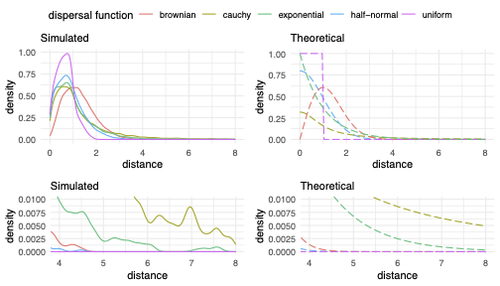

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

05 Oct 2017

Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local AdaptationStewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips 10.1101/145169A new approach to identifying drivers of local adaptationRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer based on reviews by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Thomas LenormandLocal adaptation, the higher fitness a population achieves in its local “home” environment relative to other environments is a crucial phase in the divergence of populations, and as such both generates and maintains diversity. Local adaptation is enhanced by selection and genetic variation in the relevant traits, and decreased by gene flow and genetic drift. Demonstrating local adaptation is laborious, and is typically done with a reciprocal transplant design [1], documenting repeated geographic clines [e.g. 2, 3] also provides strong evidence of local adaptation. Even when well documented, it is often unknown which aspects of the environment impose selection. Indeed, differences in environment between different sites that are measured during studies of local adaptation explain little of the variance in the degree of local adaptation [4]. This poses a problem to population management. Given climate change and habitat destruction, understanding the environmental drivers of local adaptation can be crucially important to conducting successful assisted migration or targeted gene flow. In this manuscript, Macdonald et al. [5] propose a means of identifying which aspects of the environment select for local adaptation without conducting a reciprocal transplant experiment. The idea is that the strength of relationships between traits and environmental variables that are due to plastic responses to the environment will not be influenced by gene flow, but the strength of trait-environment relationships that are due to local adaptation should decrease with gene flow. This then can be used to reduce the somewhat arbitrary list of environmental variables on which data are available down to a targeted list more likely to drive local adaptation in specific traits. To perform such an analysis requires three things: 1) measurements of traits of interest in a species across locations, 2) an estimate of gene flow between locations, which can be replaced with a biologically meaningful estimate of how well connected those locations are from the point of view of the study species, and 3) data on climate and other environmental variables from across a species’ range, many of which are available on line. Macdonald et al. [5] demonstrate their approach using a skink (Lampropholis coggeri). They collected morphological and physiological data on individuals from multiple populations. They estimated connectivity among those locations using information on habitat suitability and dispersal potential [6], and gleaned climatic data from available databases and the literature. They find that two physiological traits, the critical minimum and maximum temperatures, show the strongest signs of local adaptation, specifically local adaptation to annual mean precipitation, precipitation of the driest quarter, and minimum annual temperature. These are then aspects of skink phenotype and skink habitats that could be explored further, or could be used to provide background information if migration efforts, for example for genetic rescue [7] were initiated. The approach laid out has the potential to spark a novel genre of research on local adaptation. It its simplest form, knowing that local adaptation is eroded by gene flow, it is intuitive to consider that if connectivity reduces the strength of the relationship between an environmental variable and a trait, that the trait might be involved in local adaptation. The approach is less intuitive than that, however – it relies not connectivity per-se, but the interaction between connectivity and different environmental variables and how that interaction alters trait-environment relationships. The authors lay out a number of useful caveats and potential areas that could use further development. It will be interesting to see how the community of evolutionary biologists responds. References [1] Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL and Gandon S. 2013. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16: 1195-1205. doi: 10.1111/ele.12150 [2] Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D and Serra L. 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science, 287: 308-309. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.308 [3] Milesi P, Lenormand T, Lagneau C, Weill M and Labbé P. 2016. Relating fitness to long-term environmental variations in natura. Molecular Ecology, 25: 5483-5499. doi: 10.1111/mec.13855 [4] Hereford, J. 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. The American Naturalist 173: 579-588. doi: 10.1086/597611 [5] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J and Phillips BL. 2017. Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 of October 4, 2017. doi: 10.1101/145169 [6] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J, Moritz C and Phillips BL. 2017. Peripheral isolates as sources of adaptive diversity under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00088 [7] Whiteley AR, Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC and Tallmon DA. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.009 | Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local Adaptation | Stewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips | Despite being able to conclusively demonstrate local adaptation, we are still often unable to objectively determine the climatic drivers of local adaptation. Given the rapid rate of global change, understanding the climatic drivers of local adapta... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | Thomas Lenormand | 2017-06-06 13:06:54 | View |

30 Aug 2021

The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactionsMoury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Juliette, Fabre Frédéric, Fournet Sylvain, Grimault Valérie, Jaunet Thierry, Justafré Isabelle, Lefebvre Véronique, Losdat Denis, Marcel Thierry C., Montarry Josselin, Morris Cindy E., Omrani Mariem, Paineau Manon, Perrot Sophie, Pilet-Nayel Marie-Laure, R... https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745Nestedness and modularity in plant-parasite infection networksRecommended by Santiago Elena based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers

In a landmark paper, Flores et al. (2011) showed that the interactions between bacteria and their viruses could be nicely described using a bipartite infection networks. Two quantitative properties of these networks were of particular interest, namely modularity and nestedness. Modularity emerges when groups of host species (or genotypes) shared groups of viruses. Nestedness provided a view of the degree of specialization of both partners: high nestedness suggests that hosts differ in their susceptibility to infection, with some highly susceptible host genotypes selecting for very specialized viruses while strongly resistant host genotypes select for generalist viruses. Translated to the plant pathology parlance, this extreme case would be equivalent to a gene-for-gene infection model (Flor 1956): new mutations confer hosts with resistance to recently evolved viruses while maintaining resistance to past viruses. Likewise, virus mutations for expanding host range evolve without losing the ability to infect ancestral host genotypes. By contrast, a non-nested network would represent a matching-allele infection model (Frank 2000) in which each interacting organism evolves by losing its capacity to resist/infect its ancestral partners, resembling a Red Queen dynamic. Obviously, the reality is more complex and may lie anywhere between these two extreme situations. Recently, Valverde et al. (2020) developed a model to explain the emergence of nestedness and modularity in plant-virus infection networks across diverse habitats. They found that local modularity could coexist with global nestedness and that intraspecific competition was the main driver of the evolution of ecosystems in a continuum between nested-modular and nested networks. These predictions were tested with field data showing the association between plant host species and different viruses in different agroecosystems (Valverde et al. 2020). The effect of interspecific competition in the structure of empirical plant host-virus infection networks was also tested by McLeish et al. (2019). Besides data from agroecosystems, evolution experiments have also shown the pervasive emergence of nestedness during the diversification of independently-evolved lineages of potyviruses in Arabidopsis thaliana genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection (Hillung et al. 2014; González et al. 2019; Navarro et al. 2020). In their study, Moury et al. (2021) have expanded all these previous observations to a diverse set of pathosystems that range from viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes to insects. While modularity was barely seen in only a few of the systems, nestedness was a common trend (observed in ~94% of all systems). This nestedness, as seen in previous studies and as predicted by theory, emerged as a consequence of the existence of generalist and specialist strains of the parasites that differed in their capacity to infect more or less resistant plant genotypes. As pointed out by Moury et al. (2021) in their conclusions, the ubiquity of nestedness in plant-parasite infection matrices has strong implications for the evolution and management of infectious diseases. References Flor, H. H. (1956). The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics, 8, 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8 Flores, C. O., Meyer, J. R., Valverde, S., Farr, L., and Weitz, J. S. (2011). Statistical structure of host–phage interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, E288-E297. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101595108 Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 202, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054 González, R., Butković, A., and Elena, S. F. (2019). Role of host genetic diversity for susceptibility-to-infection in the evolution of virulence of a plant virus. Virus evolution, 5(2), vez024. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez052 Hillung, J., Cuevas, J. M., Valverde, S., and Elena, S. F. (2014). Experimental evolution of an emerging plant virus in host genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection. Evolution, 68, 2467-2480. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12458 McLeish, M., Sacristán, S., Fraile, A., and García-Arenal, F. (2019). Coinfection organizes epidemiological networks of viruses and hosts and reveals hubs of transmission. Phytopathology, 109, 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0293-R Moury B, Audergon J-M, Baudracco-Arnas S, Krima SB, Bertrand F, Boissot N, Buisson M, Caffier V, Cantet M, Chanéac S, Constant C, Delmotte F, Dogimont C, Doumayrou J, Fabre F, Fournet S, Grimault V, Jaunet T, Justafré I, Lefebvre V, Losdat D, Marcel TC, Montarry J, Morris CE, Omrani M, Paineau M, Perrot S, Pilet-Nayel M-L and Ruellan Y (2021) The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433745, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745 Navarro, R., Ambros, S., Martinez, F., Wu, B., Carrasco, J. L., and Elena, S. F. (2020). Defects in plant immunity modulate the rates and patterns of RNA virus evolution. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.13.337402 Valverde, S., Vidiella, B., Montañez, R., Fraile, A., Sacristán, S., and García-Arenal, F. (2020). Coexistence of nestedness and modularity in host–pathogen infection networks. Nature ecology & evolution, 4, 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1130-9 | The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions | Moury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Jul... | <p>Understanding the relationships between host range and pathogenicity for parasites, and between the efficiency and scope of immunity for hosts are essential to implement efficient disease control strategies. In the case of plant parasites, most... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Species interactions | Santiago Elena | 2021-03-04 21:23:08 | View | |

23 Jun 2021

Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic driftLaurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230Separating adaptation from drift: A cautionary tale from a self-fertilizing plantRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Pierre Olivier Cheptou, Jon Agren and Stefan LaurentIn recent years many studies have documented shifts in phenology in response to climate change, be it in arrival times in migrating birds, budset in trees, adult emergence in butterflies, or flowering time in annual plants (Coen et al. 2018; Piao et al. 2019). While these changes are, in part, explained by phenotypic plasticity, more and more studies find that they involve also genetic changes, that is, they involve evolutionary change (e.g., Metz et al. 2020). Yet, evolutionary change may occur through genetic drift as well as selection. Therefore, in order to demonstrate adaptive evolutionary change in response to climate change, drift has to be excluded as an alternative explanation (Hansen et al. 2012). A new study by Gay et al. (2021) shows just how difficult this can be. The authors investigated a recent evolutionary shift in flowering time by in a population an annual plant that reproduces predominantly by self-fertilization. The population has recently been subjected to increased temperatures and reduced rainfalls both of which are believed to select for earlier flowering times. They used a “resurrection” approach (Orsini et al. 2013; Weider et al. 2018): Genotypes from the past (resurrected from seeds) were compared alongside more recent genotypes (from more recently collected seeds) under identical conditions in the greenhouse. Using an experimental design that replicated genotypes, eliminated maternal effects, and controlled for microenvironmental variation, they found said genetic change in flowering times: Genotypes obtained from recently collected seeds flowered significantly (about 2 days) earlier than those obtained 22 generations before. However, neutral markers (microsatellites) also showed strong changes in allele frequencies across the 22 generations, suggesting that effective population size, Ne, was low (i.e., genetic drift was strong), which is typical for highly self-fertilizing populations. In addition, several multilocus genotypes were present at high frequencies and persisted over the 22 generations, almost as in clonal populations (e.g., Schaffner et al. 2019). The challenge was thus to evaluate whether the observed evolutionary change was the result of an adaptive response to selection or may be explained by drift alone. Here, Gay et al. (2021) took a particularly careful and thorough approach. First, they carried out a selection gradient analysis, finding that earlier-flowering plants produced more seeds than later-flowering plants. This suggests that, under greenhouse conditions, there was indeed selection for earlier flowering times. Second, investigating other populations from the same region (all populations are located on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, France), they found that a concurrent shift to earlier flowering times occurred also in these populations. Under the hypothesis that the populations can be regarded as independent replicates of the evolutionary process, the observation of concurrent shifts rules out genetic drift (under drift, the direction of change is expected to be random). The study may well have stopped here, concluding that there is good evidence for an adaptive response to selection for earlier flowering times in these self-fertilizing plants, at least under the hypothesis that selection gradients estimated in the greenhouse are relevant to field conditions. However, the authors went one step further. They used the change in the frequencies of the multilocus genotypes across the 22 generations as an estimate of realized fitness in the field and compared them to the phenotypic assays from the greenhouse. The results showed a tendency for high-fitness genotypes (positive frequency changes) to flower earlier and to produce more seeds than low-fitness genotypes. However, a simulation model showed that the observed correlations could be explained by drift alone, as long as Ne is lower than ca. 150 individuals. The findings were thus consistent with an adaptive evolutionary change in response to selection, but drift could only be excluded as the sole explanation if the effective population size was large enough. The study did provide two estimates of Ne (19 and 136 individuals, based on individual microsatellite loci or multilocus genotypes, respectively), but both are problematic. First, frequency changes over time may be influenced by the presence of a seed bank or by immigration from a genetically dissimilar population, which may lead to an underestimation of Ne (Wang and Whitlock 2003). Indeed, the low effective size inferred from the allele frequency changes at microsatellite loci appears to be inconsistent with levels of genetic diversity found in the population. Moreover, high self-fertilization reduces effective recombination and therefore leads to non-independence among loci. This lowers the precision of the Ne estimates (due to a higher sampling variance) and may also violate the assumption of neutrality due to the possibility of selection (e.g., due to inbreeding depression) at linked loci, which may be anywhere in the genome in case of high degrees of self-fertilization. There is thus no definite answer to the question of whether or not the observed changes in flowering time in this population were driven by selection. The study sets high standards for other, similar ones, in terms of thoroughness of the analyses and care in interpreting the findings. It also serves as a very instructive reminder to carefully check the assumptions when estimating neutral expectations, especially when working on species with complicated demographies or non-standard life cycles. Indeed the issues encountered here, in particular the difficulty of establishing neutral expectations in species with low effective recombination, may apply to many other species, including partially or fully asexual ones (Hartfield 2016). Furthermore, they may not be limited to estimating Ne but may also apply, for instance, to the establishment of neutral baselines for outlier analyses in genome scans (see e.g, Orsini et al. 2012). References Cohen JM, Lajeunesse MJ, Rohr JR (2018) A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 8, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0067-3 Gay L, Dhinaut J, Jullien M, Vitalis R, Navascués M, Ranwez V, Ronfort J (2021) Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift. bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.261230, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230 Hansen MM, Olivieri I, Waller DM, Nielsen EE (2012) Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Molecular Ecology, 21, 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05463.x Hartfield M (2016) Evolutionary genetic consequences of facultative sex and outcrossing. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 29, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12770 Metz J, Lampei C, Bäumler L, Bocherens H, Dittberner H, Henneberg L, Meaux J de, Tielbörger K (2020) Rapid adaptive evolution to drought in a subset of plant traits in a large-scale climate change experiment. Ecology Letters, 23, 1643–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13596 Orsini L, Schwenk K, De Meester L, Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Weider LJ (2013) The evolutionary time machine: using dormant propagules to forecast how populations can adapt to changing environments. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.009 Orsini L, Spanier KI, Meester LD (2012) Genomic signature of natural and anthropogenic stress in wild populations of the waterflea Daphnia magna: validation in space, time and experimental evolution. Molecular Ecology, 21, 2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05429.x Piao S, Liu Q, Chen A, Janssens IA, Fu Y, Dai J, Liu L, Lian X, Shen M, Zhu X (2019) Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Global Change Biology, 25, 1922–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14619 Schaffner LR, Govaert L, De Meester L, Ellner SP, Fairchild E, Miner BE, Rudstam LG, Spaak P, Hairston NG (2019) Consumer-resource dynamics is an eco-evolutionary process in a natural plankton community. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0960-9 Wang J, Whitlock MC (2003) Estimating Effective Population Size and Migration Rates From Genetic Samples Over Space and Time. Genetics, 163, 429–446. PMID: 12586728 Weider LJ, Jeyasingh PD, Frisch D (2018) Evolutionary aspects of resurrection ecology: Progress, scope, and applications—An overview. Evolutionary Applications, 11, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12563 | Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift | Laurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resurrection studies are a useful tool to measure how phenotypic traits have changed in populations through time. If these traits modifications correlate with the environmental changes that occurred during the time ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2020-08-21 17:26:59 | View | ||

25 Jan 2023

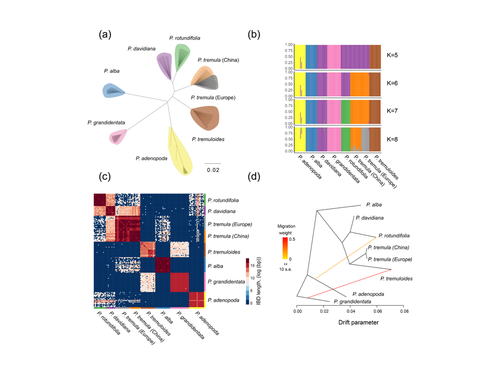

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosisHusnik F, McCutcheon JP doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603910113Obligate dependence does not preclude changing partners in a Russian dolls symbiotic systemRecommended by Emmanuelle Jousselin and Fabrice VavreSymbiotic associations with bacterial partners have facilitated important evolutionary transitions in the life histories of eukaryotes. For instance, many insects have established long-term interactions with intracellular bacteria that provide them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. However, despite the high level of interdependency among organisms involved in endosymbiotic systems, examples of symbiont replacements along the evolutionary history of insect hosts are numerous.

In their paper, Husnik and McCutcheon [1] test the stability of symbiotic systems in a particularly imbricated Russian-doll type interaction, where one bacterium lives insides another bacterium, which itself lives inside insect cells. For their study, they chose representative species of mealybugs (Pseudococcidae), a species rich group of sap-feeding insects that hosts diverse and complex symbiotic systems. In species of the subfamily Pseudococcinae, data published so far suggest that the primary symbiont, a ß-proteobacterium named Tremblaya princeps, is supplemented by a second bacterial symbiont (a ϒ-proteobaterium) that lives within its cytoplasm; both participate to the metabolic pathways that provide essential amino acids and vitamins to their hosts. Here, Husnik and McCutcheon generate host and endosymbiont genome data for five phylogenetically divergent species of Pseudococcinae in order to better understand: 1) the evolutionary history of the symbiotic associations; 2) the metabolic roles of each partner, 3) the timing and origin of Horizontal Gene Transfers (HGT) between the hosts and their symbionts. Reference [1] Husnik F., McCutcheon JP. 2016. Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. PNAS 113: E5416-E5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603910113 | Repeated replacements of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis | Husnik F, McCutcheon JP | Stable endosymbiosis of a bacterium into a host cell promotes cellular and genomic complexity. The mealybug *Planococcus citri* has two bacterial endosymbionts with an unusual nested arrangement: the γ-proteobacterium *Moranella endobia* lives in ... |  | Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Emmanuelle Jousselin | 2016-12-13 14:27:09 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer