Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax)Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. doi:10.1038/ng.3430Supergene Control of a Reproductive PolymorphismRecommended by Thomas Flatt and Laurent KellerTwo back-to-back papers published earlier this year in Nature Genetics provide compelling evidence for the control of a male reproductive polymorphism in a wading bird by a "supergene", a cluster of tightly linked genes [1-2]. The bird in question, the ruff (Philomachus pugnax), has a rather unusual reproductive system that consists of three distinct types of males ("reproductive morphs"): aggressive "independents" who represent the majority of males; a smaller fraction of non-territorial "satellites" who are submissive towards "independents"; and "faeders" who mimic females and are rare. Previous work has shown that the male morphs differ in major aspects of mating and aggression behavior, plumage coloration and body size, and that – intriguingly – this complex multi-trait polymorphism is apparently controlled by a single autosomal Mendelian locus with three alleles [3]. To uncover the genetic control of this polymorphism two independent teams, led by Terry Burke [1] and Leif Andersson [2], have set out to analyze the genomes of male ruffs. Using a combination of genomics and genetics, both groups managed to pin down the supergene locus and map it to a non-recombining, 4.5 Mb large inversion which arose 3.8 million years ago. While "independents" are homozygous for the ancestral uninverted sequence, "satellites" and "faeders" carry evolutionarily divergent, dominant alternative haplotypes of the inversion. Thus, as in several other notable cases, for example the supergene control of disassortative mating, aggressiveness and plumage color in white-throated sparrows [4], of mimicry in Heliconius and Papilio butterflies [5-6], or of social structure in ants [7], an inversion – behaving as a single "locus" – underpins the mechanistic basis of the supergene. More generally, and beyond inversions, a growing number of studies now shows that selection can favor the evolution of suppressed recombination, thereby leading to the emergence of clusters of tightly linked loci which can then control – presumably due to polygenic gene action – a suite of complex phenotypes [8-10]. A largely unresolved question in this field concerns the identity of the causative alleles and loci within a given supergene. Recent progress on this question has been made for example in Papilio polytes butterflies where a mimicry supergene has been found to involve – surprisingly – only a single but large gene: multiple mimicry alleles in the doublesex gene are maintained in strong linkage disequilibrium via an inversion. It will clearly be of great interest to see future examples of such a fine-scale genetic dissection of supergenes. In conclusion, we were impressed by the data and analyses of Küpper et al. [1] and Lamichhaney et al. [2]: both papers beautifully illustrate how genomics and evolutionary ecology can be combined to make new, exciting discoveries. Both papers will appeal to readers with an interest in supergenes, inversions, the interplay of selection and recombination, or the genetic control of complex phenotypes. References [1] Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, et al. 2016. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nature Genetics 48:79-83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443 [2] Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nature Genetics 48:84-88. doi: 10.1038/ng.3430 [3] Lank DB, Smith CM, Hanotte O, Burke T, Cooke F. 1995. Genetic polymorphism for alternative mating behaviour in lekking male ruff Philomachus pugnax. Nature 378:59-62. doi: 10.1038/378059a0 [4] Tuttle Elaina M, Bergland Alan O, Korody Marisa L, Brewer Michael S, Newhouse Daniel J, Minx P, Stager M, Betuel A, Cheviron Zachary A, Warren Wesley C, et al. 2016. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Current Biology 26:344-350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069 [5] Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477:203-206. doi: 10.1038/nature10341 [6] Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507:229-232. doi: 10.1038/nature13112 [7] Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493:664-668. doi: 10.1038/nature11832 [8] Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113:1-8. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.20 [9] Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes. Current Biology 24:R288-R294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056 [10] Charlesworth D. 2015. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evolutionary Applications 9:74-90. doi: 10.1111/eva.12291 | Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax) | Lamichhaney S, Fan G, Widemo F, Gunnarsson U, Thalmann DS, Hoeppner MP, Kerje S, Gustafson U, Shi C, Zhang H, et al. | The ruff is a Palearctic wader with a spectacular lekking behavior where highly ornamented males compete for females1, 2, 3, 4. This bird has one of the most remarkable mating systems in the animal kingdom, comprising three different male morphs (... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Flatt | 2016-12-13 17:46:54 | View | |

04 Nov 2020

Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistanceSamuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.970905More intense symptoms, more treatment, more drug-resistance: coevolution of virulence and drug-resistanceRecommended by Ludek Berec based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersMathematical models play an essential role in current evolutionary biology, and evolutionary epidemiology is not an exception [1]. While the issues of virulence evolution and drug-resistance evolution resonate in the literature for quite some time [2, 3], the study by Alizon [4] is one of a few that consider co-evolution of both these traits [5]. The idea behind this study is the following: treating individuals with more severe symptoms at a higher rate (which appears to be quite natural) leads to an appearance of virulent drug-resistant strains, via treatment failure. The author then shows that virulence in drug-resistant strains may face different selective pressures than in drug-sensitive strains and hence proceed at different rates. Hence, treatment itself modulates evolution of virulence. As one of the reviewers emphasizes, the present manuscript offers a mathematical view on why the resistant and more virulent strains can be selected in epidemics. Also, we both find important that the author highlights that the topic and results of this study can be attributed to public health policies and development of optimal treatment protocols [6]. References [1] Gandon S, Day T, Metcalf JE, Grenfell BT (2016) Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends Ecol Evol 31: 776-788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistance | Samuel Alizon | <p>Antimicrobial therapeutic treatments are by definition applied after the onset of symptoms, which tend to correlate with infection severity. Using mathematical epidemiology models, I explore how this link affects the coevolutionary dynamics bet... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Ludek Berec | 2020-03-04 10:18:39 | View | |

13 Apr 2023

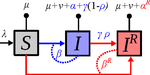

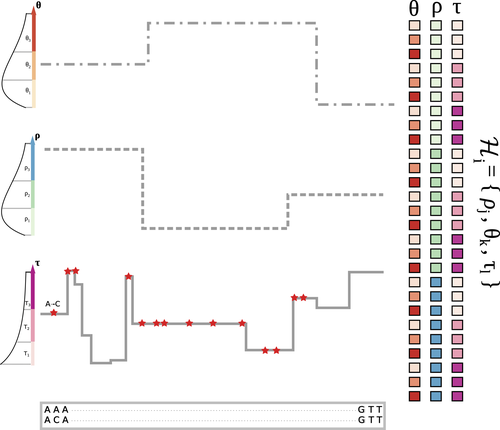

The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variationGustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667An unusual suspect: the mutation landscape as a determinant of local variation in nucleotide diversityRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by David Castellano and 1 anonymous reviewerSometimes, important factors for explaining biological processes fall through the cracks, and it is only through careful modeling that their importance eventually comes out to light. In this study, Barroso and Dutheil introduce a new method based on the sequentially Markovian coalescent (SMC, Marjoran and Wall 2006) for jointly estimating local recombination and coalescent rates along a genome. Unlike previous SMC-based methods, however, their method can also co-estimate local patterns of variation in mutation rates. This is a powerful improvement which allows them to tackle questions about the reasons for the extensive variation in nucleotide diversity across the chromosomes of a species - a problem that has plagued the minds of population geneticists for decades (Begun and Aquadro 1992, Andolfatto 2007, McVicker et al., 2009, Pouyet and Gilbert 2021). The authors find that variation in de novo mutation rates appears to be the most important factor in determining nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster. Though seemingly contradicting previous attempts at addressing this problem (Comeron 2014), they take care to investigate and explain why that might be the case. Barroso and Dutheil have also taken care to carefully explain the details of their new approach and have carried a very thorough set of analyses comparing competing explanations for patterns of nucleotide variation via causal modeling. The reviewers raised several issues involving choices made by the authors in their analysis of variance partitioning, the proper evaluation of the role of linked selection and the recombination rate estimates emerging from their model. These issues have all been extensively addressed by the authors, and their conclusions seem to remain robust. The study illustrates why the mutation landscape should not be ignored as an important determinant of local variation in genetic diversity, and opens up questions about the generalizability of these results to other organisms. REFERENCES Andolfatto, P. (2007). Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome research, 17(12), 1755-1762. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.6691007 Barroso, G. V., & Dutheil, J. Y. (2021). The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation. bioRxiv, 2021.09.16.460667, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667 Begun, D. J., & Aquadro, C. F. (1992). Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature, 356(6369), 519-520. https://doi.org/10.1038/356519a0 Comeron, J. M. (2014). Background selection as baseline for nucleotide variation across the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genetics, 10(6), e1004434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004434 Marjoram, P., & Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast" coalescent" simulation. BMC genetics, 7, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16 McVicker, G., Gordon, D., Davis, C., & Green, P. (2009). Widespread genomic signatures of natural selection in hominid evolution. PLoS genetics, 5(5), e1000471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471 Pouyet, F., & Gilbert, K. J. (2021). Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. Peer Community Journal, 1, e27. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.16 | The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation | Gustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil | <p style="text-align: justify;">What shapes the distribution of nucleotide diversity along the genome? Attempts to answer this question have sparked debate about the roles of neutral stochastic processes and natural selection in molecular evolutio... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-10-30 07:52:07 | View | |

18 May 2018

Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkageKatie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins https://doi.org/10.1101/202481Differential effect of genes in diverse environments, their role in local adaptation and the interference between genes that are physically linkedRecommended by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerThe genome of eukaryotic species is a complex structure that experience many different interactions within itself and with the surrounding environment. The genetic architecture of a phenotype (that is, the set of genetic elements affecting a trait of the organism) plays a fundamental role in understanding the adaptation process of a species to, for example, different climate environments, or to its interaction with other species. Thus, it is fundamental to study the different aspects of the genetic architecture of the species and its relationship with its surronding environment. Aspects such as modularity (the number of genetic units and the degree to which each unit is affecting a trait of the organism), pleiotropy (the number of different effects that a genetic unit can have on an organism) or linkage (the degree of association between the different genetic units) are essential to understand the genetic architecture and to interpret the effects of selection on the genome. Indeed, the knowledge of the different aspects of the genetic architecture could clarify whether genes are affected by multiple aspects of the environment or, on the contrary, are affected by only specific aspects [1,2]. The work performed by Lotterhos et al. [3] sought to understand the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments in lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), considering as candidate SNPs those previously detected as a result of its extreme association patterns to different environmental variables or to extreme population differentiation. This consideration is very important because the study is only relevant if the studied markers are under the effect of selection. Otherwise, the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments would be masked by other (neutral) kind of associations that would be difficult to interpret [4,5]. In order to understand the relationship between genetic architecture and adaptation, it is relevant to detect the association networks of the candidate SNPs with climate variables (a way to measure modularity) and if these SNPs (and loci) are affected by single or multiple environments (a way to measure pleiotropy). The authors used co-association networks, an innovative approach in this field, to analyse the interaction between the environmental information and the genetic polymorphism of each individual. This methodology is more appropriate than other multivariate methods - such as analysis based on principal components - because it is possible to cluster SNPs based on associations with similar environmental variables. In this sense, the co-association networks allowed to both study the genetic and physical linkage between different co-associations modules but also to compare two different models of evolution: a Modular environmental response architecture (specific genes are affected by specific aspects of the environment) or a Universal pleiotropic environmental response architecture (all genes are affected by all aspects of the environment). The representation of different correlations between allelic frequency and environmental factors (named galaxy biplots) are especially informative to understand the effect of the different clusters on specific aspects of the environment (for example, the co-association network ‘Aridity’ shows strong associations with hot/wet versus cold/dry environments). The analysis performed by Lotterhos et al. [3], although it has some unavoidable limitations (e.g., only extreme candidate SNPs are selected, limiting the results to the stronger effects; the genetic and physical map is incomplete in this species), includes relevant results and also implements new methodologies in the field. To highlight some of them: the preponderance of a Modular environmental response architecture (evolution in separated modules), the detection of physical linkage among SNPs that are co-associated with different aspects of the environment (which was unexpected a priori), the implementation of co-association networks and galaxy biplots to see the effect of modularity and pleiotropy on different aspects of environment. Finally, this work contains remarkable introductory Figures and Tables explaining unambiguously the main concepts [6] included in this study. This work can be treated as a starting point for many other future studies in the field. References [1] Hancock AM, Brachi B, Faure N, Horton MW, Jarymowycz LB, Sperone FG, Toomajian C, Roux F & Bergelson J. 2011. Adaptation to climate across the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Science 334: 83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1209244 | Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkage | Katie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins | <p>Background: Physical linkage among genes shaped by different sources of selection is a fundamental aspect of genetic architecture. Theory predicts that evolution in complex environments selects for modular genetic architectures and high recombi... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution | Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins | 2017-10-15 19:21:57 | View | |

12 Nov 2020

Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentThibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentRecommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome. References [1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 | Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

23 Apr 2020

How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridisJulien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Estoup, Benoit Facon https://doi.org/10.1101/849968Selection on a single trait does not recapitulate the evolution of life-history traits seen during an invasionRecommended by Inês Fragata and Ben Phillips based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersBiological invasions are natural experiments, and often show that evolution can affect dynamics in important ways [1-3]. While we often think of invasions as a conservation problem stemming from anthropogenic introductions [4,5], biological invasions are much more commonplace than this, including phenomena as diverse as natural range shifts, the spread of novel pathogens, and the growth of tumors. A major question across all these settings is which set of traits determine the ability of a population to invade new space [6,7]. Traits such as: increased growth or reproductive rate, dispersal ability and ability to defend from predation often show large evolutionary shifts across invasion history [1,6,8]. Are such multi-trait shifts driven by selection on multiple traits, or a correlated response by multiple traits to selection on one? Resolving this question is important for both theoretical and practical reasons [9,10]. But despite the importance of this issue, it is not easy to perform the necessary manipulative experiments [9]. References [1] Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S. et al. (2001). The population biology of invasive species. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 32(1), 305-332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 | How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridis | Julien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Est... | <p>Experiments comparing native to introduced populations or distinct introduced populations to each other show that phenotypic evolution is common and often involves a suit of interacting phenotypic traits. We define such sets of traits that evol... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Inês Fragata | 2019-11-29 07:07:00 | View | |

13 Sep 2019

Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A.Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati https://doi.org/10.1101/622373New curation method for microsatellite markers improves population genetics analysesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Eric Petit, Martin Husemann and 2 anonymous reviewersGenetic markers are used for in modern population genetics/genomics to uncover the past neutral and selective history of population and species. Besides Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) obtained from whole genome data, microsatellites (or Short Tandem Repeats, SSR) have been common markers of choice in numerous population genetics studies of non-model species with large sample sizes [1]. Microsatellites can be used to uncover and draw inference of the past population demography (e.g. expansion, decline, bottlenecks…), population split, population structure and gene flow, but also life history traits and modes of reproduction (e.g. [2,3]). These markers are widely used in conservation genetics [4] or to study parasites or disease vectors [5]. Microsatellites do show higher mutation rate than SNPs increasing, on the one hand, the statistical power to infer recent events (for example crop domestication, [2,3]), while, on the other hand, decreasing their statistical power over longer time scales due to homoplasy [6]. References [1] Jarne, P., and Lagoda, P. J. (1996). Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends in ecology & evolution, 11(10), 424-429. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10049-5 | Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A. | Thierry De Meeûs, Cynthia T. Chan, John M. Ludwig, Jean I. Tsao, Jaymin Patel, Jigar Bhagatwala, and Lorenza Beati | <p>Null alleles, short allele dominance (SAD), and stuttering increase the perceived relative inbreeding of individuals and subpopulations as measured by Wright’s FIS and FST. Ascertainment bias, due to such amplifying problems are usually caused ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Other, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2019-05-02 20:52:08 | View | |

06 Oct 2017

Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebratesFrancisco J. Novo https://doi.org/10.1101/150482Combining molecular information on chromatin organisation with eQTLs and evolutionary conservation provides strong candidates for the evolution of gene regulation in mammalian brainsRecommended by Marc Robinson-Rechavi based on reviews by Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Charles DankoIn this manuscript [1], Francisco J. Novo proposes candidate non-coding genomic elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes. What is very nice about this study is the way in which public molecular data, including physical interaction data, is used to leverage recent advances in our understanding to molecular mechanisms of gene regulation in an evolutionary context. More specifically, evolutionarily conserved non coding sequences are combined with enhancers from the FANTOM5 project, DNAse hypersensitive sites, chromatin segmentation, ChIP-seq of transcription factors and of p300, gene expression and eQTLs from GTEx, and physical interactions from several Hi-C datasets. The candidate regulatory regions thus identified are linked to candidate regulated genes, and the author shows their potential implication in brain development. While the results are focused on a small number of genes, this allows to verify features of these candidates in great detail. This study shows how functional genomics is increasingly allowing us to fulfill the promises of Evo-Devo: understanding the molecular mechanisms of conservation and differences in morphology. References [1] Novo, FJ. 2017. Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 150482, ver. 4 of Sept 29th, 2017. doi: 10.1101/150482 | Evolutionary analysis of candidate non-coding elements regulating neurodevelopmental genes in vertebrates | Francisco J. Novo | <p>Many non-coding regulatory elements conserved in vertebrates regulate the expression of genes involved in development and play an important role in the evolution of morphology through the rewiring of developmental gene networks. Available biolo... |  | Genome Evolution | Marc Robinson-Rechavi | Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Charles Danko | 2017-06-29 08:55:41 | View |

06 Feb 2024

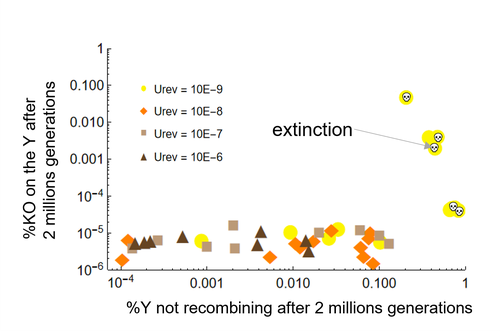

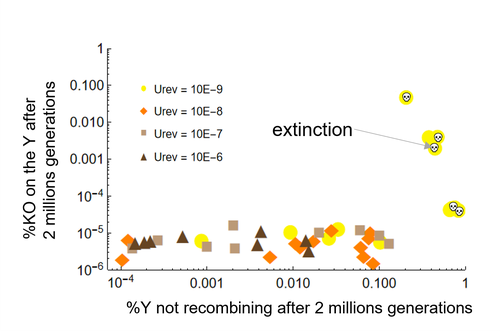

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View | |

20 Jan 2020

A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random ForestMarie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup https://doi.org/10.1101/671867Estimating recent divergence history: making the most of microsatellite data and Approximate Bayesian Computation approachesRecommended by Takeshi Kawakami and Concetta Burgarella based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield and 2 anonymous reviewersThe present-day distribution of extant species is the result of the interplay between their past population demography (e.g., expansion, contraction, isolation, and migration) and adaptation to the environment. Shedding light on the timing and magnitude of key demographic events helps identify potential drivers of such events and interaction of those drivers, such as life history traits and past episodes of environmental shifts. The understanding of the key factors driving species evolution gives important insights into how the species may respond to changing conditions, which can be particularly relevant for the management of harmful species, such as agricultural pests (e.g. [1]). Meaningful demographic inferences present major challenges. These include formulating evolutionary scenarios fitting species biology and the eco-geographical context and choosing informative molecular markers and accurate quantitative approaches to statistically compare multiple demographic scenarios and estimate the parameters of interest. A further issue comes with result interpretation. Accurately dating the inferred events is far from straightforward since reliable calibration points are necessary to translate the molecular estimates of the evolutionary time into absolute time units (i.e. years). This can be attempted in different ways, such as by using fossil and archaeological records, heterochronous samples (e.g. ancient DNA), and/or mutation rate estimated from independent data (e.g. [2], [3] for review). Nonetheless, most experimental systems rarely meet these conditions, hindering the comprehensive interpretation of results. The contribution of Chapuis et al. [4] addresses these issues to investigate the recent history of the African insect pest Schistocerca gregaria (desert locust). They apply Approximate Bayesian Computation-Random Forest (ABC-RF) approaches to microsatellite markers. Owing to their fast mutation rate microsatellite markers offer at least two advantages: i) suitability for analyzing recently diverged populations, and ii) direct estimate of the germline mutation rate in pedigree samples. The work of Chapuis et al. [4] benefits of both these advantages, since they have estimates of mutation rate and allele size constraints derived from germline mutations in the species [5]. The main aim of the study is to infer the history of divergence of the two subspecies of the desert locust, which have spatially disjoint distribution corresponding to the dry regions of North and West-South Africa. They first use paleo-vegetation maps to formulate hypotheses about changes in species range since the last glacial maximum. Based on them, they generate 12 divergence models. For the selection of the demographic model and parameter estimation, they apply the recently developed ABC-RF approach, a powerful inferential tool that allows optimizing the use of summary statistics information content, among other advantages [6]. Some methodological novelties are also introduced in this work, such as the computation of the error associated with the posterior parameter estimates under the best scenario. The accuracy of timing estimate is assured in two ways: i) by the use of microsatellite markers with known evolutionary dynamics, as underlined above, and ii) by assessing the divergence time threshold above which posterior estimates are likely to be biased by size homoplasy and limits in allele size range [7]. The best-supported model suggests a recent divergence event of the subspecies of S. gregaria (around 2.6 kya) and a reduction of populations size in one of the subspecies (S. g. flaviventris) that colonized the southern distribution area. As such, results did not support the hypothesis that the southward colonization was driven by the expansion of African dry environments associated with the last glacial maximum, as it has been postulated for other arid-adapted species with similar African disjoint distributions [8]. The estimated time of divergence points at a much more recent origin for the two subspecies, during the late Holocene, in a period corresponding to fairly stable arid conditions similar to current ones [9,10]. Although the authors cannot exclude that their microsatellite data bear limited information on older colonization events than the last one, they bring arguments in favour of alternative explanations. The hypothesis privileged does not involve climatic drivers, but the particularly efficient dispersal behaviour of the species, whose individuals are able to fly over long distances (up to thousands of kilometers) under favourable windy conditions. A single long-distance dispersal event by a few individuals would explain the genetic signature of the bottleneck. There is a growing number of studies in phylogeography in arid regions in the Southern hemisphere, but the impact of past climate changes on the species distribution in this region remains understudied relative to the Northern hemisphere [11,12]. The study presented by Chapuis et al. [4] offers several important insights into demographic changes and the evolutionary history of an agriculturally important pest species in Africa, which could also mirror the history of other organisms in the continent. As the authors point out, there are necessarily some uncertainties associated with the models of past ecosystems and climate, especially for Africa. Interestingly, the authors argue that the information on paleo-vegetation turnover was more informative than climatic niche modeling for the purpose of their study since it made them consider a wider range of bio-geographical changes and in turn a wider range of evolutionary scenarios (see discussion in Supplementary Material). Microsatellite markers have been offering a useful tool in population genetics and phylogeography for decades, but their popularity is perhaps being taken over by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (the peak year of the number of the publication with “microsatellite” is in 2012 according to PubMed). This study reaffirms the usefulness of these classic molecular markers to estimate past demographic events, especially when species- and locus-specific microsatellite mutation features are available and a powerful inferential approach is adopted. Nonetheless, there are still hurdles to overcome, such as the limitations in scenario choice associated with the simulation software used (e.g. not allowing for continuous gene flow in this particular case), which calls for further improvement of simulation tools allowing for more flexible modeling of demographic events and mutation patterns. In sum, this work not only contributes to our understanding of the makeup of the African biodiversity but also offers a useful statistical framework, which can be applied to a wide array of species and molecular markers (microsatellites, SNPs, and WGS). References [1] Lehmann, P. et al. (2018). Complex responses of global insect pests to climate change. bioRxiv, 425488. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/425488 [2] Donoghue, P. C., & Benton, M. J. (2007). Rocks and clocks: calibrating the Tree of Life using fossils and molecules. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(8), 424-431. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.05.005 [3] Ho, S. Y., Lanfear, R., Bromham, L., Phillips, M. J., Soubrier, J., Rodrigo, A. G., & Cooper, A. (2011). Time‐dependent rates of molecular evolution. Molecular ecology, 20(15), 3087-3101. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05178.x [4] Chapuis, M.-P., Raynal, L., Plantamp, C., Meynard, C. N., Blondin, L., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020). A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest. bioRxiv, 671867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/671867 5] Chapuis, M.-P., Plantamp, C., Streiff, R., Blondin, L., & Piou, C. (2015). Microsatellite evolutionary rate and pattern in Schistocerca gregaria inferred from direct observation of germline mutations. Molecular ecology, 24(24), 6107-6119. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mec.13465 [6] Raynal, L., Marin, J. M., Pudlo, P., Ribatet, M., Robert, C. P., & Estoup, A. (2018). ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35(10), 1720-1728. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 [7] Estoup, A., Jarne, P., & Cornuet, J. M. (2002). Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Molecular ecology, 11(9), 1591-1604. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01576.x [8] Moodley, Y. et al. (2018). Contrasting evolutionary history, anthropogenic declines and genetic contact in the northern and southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1890), 20181567. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1567 [9] Kröpelin, S. et al. (2008). Climate-driven ecosystem succession in the Sahara: the past 6000 years. science, 320(5877), 765-768. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1154913 [10] Maley, J. et al. (2018). Late Holocene forest contraction and fragmentation in central Africa. Quaternary Research, 89(1), 43-59. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.97 [11] Beheregaray, L. B. (2008). Twenty years of phylogeography: the state of the field and the challenges for the Southern Hemisphere. Molecular Ecology, 17(17), 3754-3774. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03857.x [12] Dubey, S., & Shine, R. (2012). Are reptile and amphibian species younger in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere?. Journal of evolutionary biology, 25(1), 220-226. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02417.x ***** A video about this preprint is available here: | A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest | Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup | <p>Dating population divergence within species from molecular data and relating such dating to climatic and biogeographic changes is not trivial. Yet it can help formulating evolutionary hypotheses regarding local adaptation and future responses t... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Takeshi Kawakami | 2019-06-20 10:31:15 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer