Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiMarianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055A valuable work lying at the crossroad of neuro-ethology, evolution and ecology in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiRecommended by Arnaud Estoup and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerAdaptations to a new ecological niche allow species to access new resources and circumvent competitors and are hence obvious pathways of evolutionary success. The evolution of agricultural pest species represents an important case to study how a species adapts, on various timescales, to a novel ecological niche. Among the numerous insects that are agricultural pests, the ability to lay eggs (or oviposit) in ripe fruit appears to be a recurrent scenario. Fruit flies (family Tephritidae) employ this strategy, and include amongst their members some of the most destructive pests (e.g., the olive fruit fly Bactrocera olea or the medfly Ceratitis capitata). In their ms, Karageorgi et al. [1] studied how Drosophila suzukii, a new major agricultural pest species that recently invaded Europe and North America, evolved the novel behavior of laying eggs into undamaged fresh fruit. The close relatives of D. suzukii lay their eggs on decaying plant substrates, and thus this represents a marked change in host use that links to substantial economic losses to the fruit industry. Although a handful of studies have identified genetic changes causing new behaviors in various species, the question of the evolution of behavior remains a largely uncharted territory. The study by Karageorgi et al. [1] represents an original and most welcome contribution in this domain for a non-model species. Using clever behavioral experiments to compare D. suzukii to several related Drosophila species, and complementing those results with neurogenetics and mutant analyses using D. suzukii, the authors nicely dissect the sensory changes at the origin of the new egg-laying behavior. The experiments they describe are easy to follow, richly illustrate through figures and images, and particularly well designed to progressively decipher the sensory bases driving oviposition of D. suzukii on ripe fruit. Altogether, Karageorgi et al.’s [1] results show that the egg-laying substrate preference of D. suzukii has considerably evolved in concert with its morphology (especially its enlarged, serrated ovipositor that enables females to pierce the skin of many ripe fruits). Their observations clearly support the view that the evolution of traits that make D. suzukii an agricultural pest included the modification of several sensory systems (i.e. mechanosensation, gustation and olfaction). These differences between D. suzukii and its close relatives collectively underlie a radical change in oviposition behavior, and were presumably instrumental in the expansion of the ecological niche of the species. The authors tentatively propose a multi-step evolutionary scenario from their results with the emergence of D. suzukii as a pest species as final outcome. Such formalization represents an interesting evolutionary model-framework that obviously would rely upon further data and experiments to confirm and refine some of the evolutionary steps proposed, especially the final and recent transition of D. suzukii from non-invasive to invasive species. References [1] Karageorgi M, Bräcker LB, Lebreton S, Minervino C, Cavey M, Siju KP, Grunwald Kadow IC, Gompel N, Prud’homme B. 2017. Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii. Current Biology, 27: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055 | Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii | Marianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme | The rise of a pest species represents a unique opportunity to address how species evolve new behaviors and adapt to novel ecological niches. We address this question by studying the egg-laying behavior of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive agricultur... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution | Arnaud Estoup | 2017-03-13 17:42:00 | View | |

20 Nov 2017

Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selectionDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze 10.1101/180000Understanding genetic variance, load, and inbreeding depression with selfingRecommended by Aneil F. Agrawal based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewerA classic problem in evolutionary biology is to understand the genetic variance in fitness. The simplest hypothesis is that variation exists, even in well-adapted populations, as a result of the balance between mutational input and selective elimination. This variation causes a reduction in mean fitness, known as the mutation load. Though mutation load is difficult to quantify empirically, indirect evidence of segregating genetic variation in fitness is often readily obtained by comparing the fitness of inbred and outbred offspring, i.e., by measuring inbreeding depression. Mutation-selection balance models have been studied as a means of understanding the genetic variance in fitness, mutation load, and inbreeding depression. Since their inception, such models have increased in sophistication, allowing us to ask these questions under more realistic and varied scenarios. The new theoretical work by Abu Awad and Roze [1] is a substantial step forward in understanding how arbitrary levels of self-fertilization affect variation, load and inbreeding depression under mutation-selection balance. References [1] Abu Awad D and Roze D. 2017. Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection. bioRxiv, 180000, ver. 4 of 17th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/180000 [2] Lande R. 1977. The influence of the mating system on the maintenance of genetic variability in polygenic characters. Genetics 86: 485–498. [3] Charlesworth D and Charlesworth B. 1987. Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 237–268. doi: 10.1111/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321 [4] Lande R and Porcher E. 2015. Maintenance of quantitative genetic variance under partial self-fertilization, with implications for the evolution of selfing. Genetics 200: 891–906. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176693 [5] Roze D. 2015. Effects of interference between selected loci on the mutation load, inbreeding depression, and heterosis. Genetics 201: 745–757. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178533 [6] Martin G and Lenormand T. 2006. A general multivariate extension of Fisher's geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60: 893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01169.x [7] Martin G, Elena SF and Lenormand T. 2007. Distributions of epistasis in microbes fit predictions from a fitness landscape model. Nature Genetics 39: 555–560. doi: 10.1038/ng1998 | Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | The mating system of a species is expected to have important effects on its genetic diversity. In this paper, we explore the effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance Vg, mutation load L and inbreeding depression δ under stabi... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Aneil F. Agrawal | 2017-08-26 09:29:20 | View | |

02 Jan 2019

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by EricaMichael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt https://doi.org/10.1101/290791The colonization history of largely isolated habitatsRecommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewersThe build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2]. References [1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790. | Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbiontsMartinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778Hooked on WolbachiaRecommended by Ana Rivero and Natacha KremerThis very nice paper by Martinez et al. [1] provides further evidence, if further evidence was needed, of the extent to which heritable microorganisms run the evolutionary show. Reference [1] Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM. 2016. Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 283:20160778. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0778 | Addicted? Reduced host resistance in populations with defensive symbionts | Martinez J, Cogni R, Cao C, Smith S, Illingworth CJR & Jiggins FM | Heritable symbionts that protect their hosts from pathogens have been described in a wide range of insect species. By reducing the incidence or severity of infection, these symbionts have the potential to reduce the strength of selection on genes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Ana Rivero | 2016-12-13 20:08:37 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS 10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in pollinat... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

09 Nov 2018

Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparumAmelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kounbobr R Dabire, Thierry Lefevre https://doi.org/10.1101/207183Malaria host manipulation increases probability of mosquitoes feeding on humansRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Olivier Restif, Ricardo S. Ramiro and 1 anonymous reviewerParasites can manipulate their host’s behaviour to ensure their own transmission. These manipulated behaviours may be outside the range of ordinary host activities [1], or alter the crucial timing and/or location of a host’s regular activity. Vantaux et al show that the latter is true for the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum [2]. They demonstrate that three species of Anopheles mosquito were 24% more likely to choose human hosts, rather than other vertebrates, for their blood feed when they harboured transmissible stages (sporozoites) compared to when they were uninfected, or infected with non-transmissible malaria parasites [2]. Host choice is crucial for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to complete its life-cycle, as their host range is much narrower than the mosquito’s for feeding; P. falciparum can only develop in hominids, or closely related apes [3]. References [1] Thomas, F., Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., Martin, G., Manu, C., Durand, P., & Renaud, F. (2002). Do hairworms (Nematomorpha) manipulate the water seeking behaviour of their terrestrial hosts? Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15(3), 356–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00410.x | Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum | Amelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kou... | <p>Whether the malaria parasite *Plasmodium falciparum* can manipulate mosquito host choice in ways that enhance parasite transmission toward human is unknown. We assessed the influence of *P. falciparum* on the blood-feeding behaviour of three of... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2018-02-28 09:12:14 | View | |

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

02 Feb 2023

Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibilityKatherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663Susceptibility to infection is not explained by sex or differences in tissue tropism across different species of DrosophilaRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Greg Hurst and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding factors explaining both intra and interspecific variation in susceptibility to infection by parasites remains a key question in evolutionary biology. Within a species variation in susceptibility is often explained by differences in behaviour affecting exposure to infection and/or resistance affecting the degree by which parasite growth is controlled (Roy & Kirchner, 2000, Behringer et al., 2000). This can vary between the sexes (Kelly et al., 2018) and may be explained by the ability of a parasite to attack different organs or tissues (Brierley et al., 2019). However, what goes on within one species is not always relevant to another, making it unclear when patterns can be scaled up and generalised across species. This is also important to understand when parasites may jump hosts, or identify species that may be susceptible to a host jump (Longdon et al., 2015). Phylogenetic distance between hosts is often an important factor explaining susceptibility to a particular parasite in plant and animal hosts (Gilbert & Webb, 2007, Faria et al., 2013). In two separate experiments, Roberts and Longdon (Roberts & Longdon, 2022) investigated how sex and tissue tropism affected variation in the load of Drosophila C Virus (DCV) across multiple Drosophila species. DCV load has been shown to correlate positively with mortality (Longdon et al., 2015). Overall, they found that load did not vary between the sexes; within a species males and females had similar DCV loads for 31 different species. There was some variation in levels of DCV growth in different tissue types, but these too were consistent across males for 7 species of Drosophila. Instead, in both experiments, host phylogeny or interspecific variation, explained differences in DCV load with some species being more infected than others. This study is neat in that it incorporates and explores simultaneously both intra and interspecific variation in infection-related life-history traits which is not often done (but see (Longdon et al., 2015, Imrie et al., 2021, Longdon et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2012). Indeed, most studies to date explore either inter-specific differences in susceptibility to a parasite (it can or can’t infect a given species) (Davies & Pedersen, 2008, Pfenning-Butterworth et al., 2021) or intra-specific variability in infection-related traits (infectivity, resistance etc.) due to factors such as sex, genotype and environment (Vale et al., 2008, Lambrechts et al., 2006). This work thus advances on previous studies, while at the same time showing that sex differences in parasite load are not necessarily pervasive. References Behringer DC, Butler MJ, Shields JD (2006) Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature, 441, 421–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/441421a Brierley L, Pedersen AB, Woolhouse MEJ (2019) Tissue tropism and transmission ecology predict virulence of human RNA viruses. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000206 Davies TJ, Pedersen AB (2008) Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.0284 Faria NR, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Streicker DG, Lemey P (2013) Simultaneously reconstructing viral cross-species transmission history and identifying the underlying constraints. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368, 20120196. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0196 Gilbert GS, Webb CO (2007) Phylogenetic signal in plant pathogen–host range. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 4979–4983. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607968104 Imrie RM, Roberts KE, Longdon B (2021) Between virus correlations in the outcome of infection across host species: Evidence of virus by host species interactions. Evolution Letters, 5, 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.247 Johnson PTJ, Rohr JR, Hoverman JT, Kellermanns E, Bowerman J, Lunde KB (2012) Living fast and dying of infection: host life history drives interspecific variation in infection and disease risk. Ecology Letters, 15, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01730.x Kelly CD, Stoehr AM, Nunn C, Smyth KN, Prokop ZM (2018) Sexual dimorphism in immunity across animals: a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters, 21, 1885–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13164 Lambrechts L, Chavatte J-M, Snounou G, Koella JC (2006) Environmental influence on the genetic basis of mosquito resistance to malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 1501–1506. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3483 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Day JP, Smith SCL, McGonigle JE, Cogni R, Cao C, Jiggins FM (2015) The Causes and Consequences of Changes in Virulence following Pathogen Host Shifts. PLOS Pathogens, 11, e1004728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004728 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Webster CL, Obbard DJ, Jiggins FM (2011) Host Phylogeny Determines Viral Persistence and Replication in Novel Hosts. PLOS Pathogens, 7, e1002260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002260 Pfenning-Butterworth AC, Davies TJ, Cressler CE (2021) Identifying co-phylogenetic hotspots for zoonotic disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376, 20200363. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0363 Roberts KE, Longdon B (2023) Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: examining sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility. bioRxiv 2022.11.01.514663, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663 Roy BA, Kirchner JW (2000) Evolutionary Dynamics of Pathogen Resistance and Tolerance. Evolution, 54, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00007.x Vale PF, Stjernman M, Little TJ (2008) Temperature-dependent costs of parasitism and maintenance of polymorphism under genotype-by-environment interactions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01555.x | Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility | Katherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Species vary in their susceptibility to pathogens, and this can alter the ability of a pathogen to infect a novel host. However, many factors can generate heterogeneity in infection outcomes, obscuring our ability t... | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | Anonymous, Greg Hurst | 2022-11-03 11:17:42 | View | |

05 Oct 2022

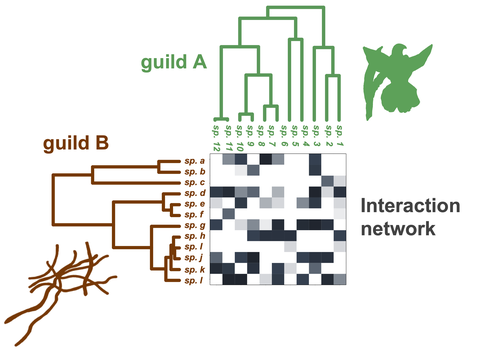

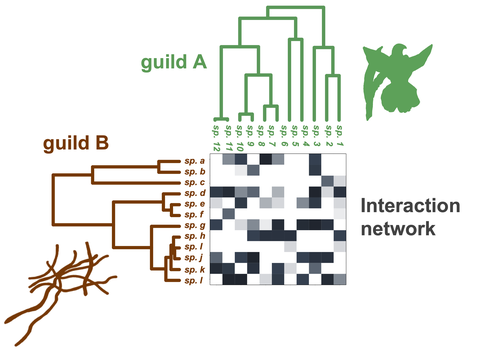

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networksBenoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networksRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720 Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157 Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192 | Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks | Benoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether interactions between species are conserved on evolutionary time-scales has spurred the development of both correlative and process-based approaches for testing phylogenetic signal in interspecific interactio... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2022-03-10 13:48:15 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer