Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichensSpribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 10.1126/science.aaf8287New partner at the core of macrolichen diversityRecommended by Enric Frago and Benoit FaconIt has long been known that most multicellular eukaryotes rely on microbial partners for a variety of functions including nutrition, immune reactions and defence against enemies. Lichens are probably the most popular example of a symbiosis involving a photosynthetic microorganism (an algae, a cyanobacteria or both) living embedded within the filaments of a fungus (usually an ascomycete). The latter is the backbone structure of the lichen, whereas the former provides photosynthetic products. Lichens are unique among symbioses because the structures the fungus and the photosynthetic microorganism form together do not resemble any of the two species living in isolation. Classic textbook examples like lichens are not often challenged and this is what Toby Spribille and his co-authors did with their paper published in July 2016 in Science [1]. This story started with the study of two species of macrolichens from the class of Lecanoromycetes that are commonly found in the mountains of Montana (US): Bryoria fremontii and B. tortuosa. For more than 90 years, these species have been known to differ in their chemical composition and colour, but studies performed so far failed in finding differences at the molecular level in both the mycobiont and the photobiont. These two species were therefore considered as nomenclatural synonyms, and the origin of their differences remained elusive. To solve this mystery, the authors of this work performed a transcriptome-wide analysis that, relative to previous studies, expanded the taxonomic range to all Fungi. This analysis revealed higher abundances of a previously unknown basidiomycete yeast from the genus Cyphobasidium in one of the lichen species, a pattern that was further confirmed by combining microscopy imaging and the fluorescent in situ hybridisation technique (FISH). Finding out that a previously unknown micro-organism changes the colour and the chemical composition of an organism is surprising but not new. For instance, bacterial symbionts are able to trigger colour changes in some insect species [2], and endophyte fungi are responsible for the production of defensive compounds in the leaves of several grasses [3]. The study by Spribille and his co-authors is fascinating because it demonstrates that Cyphobasidium yeasts have played a key role in the evolution and diversification of Lecanoromycetes, one of the most diverse classes of macrolichens. Indeed these basidiomycete yeasts were not only found in Bryoria but in 52 other lichen genera from all six continents, and these included 42 out of 56 genera in the family Parmeliaceae. Most of these sequences formed a highly supported monophyletic group, and a molecular clock revealed that the origin of many macrolichen groups occurred around the same time Cyphobasidium yeasts split from Cystobasidium, their nearest relatives. This newly discovered passenger is therefore an ancient inhabitant of lichens and has driven the evolution of this emblematic group of organisms. This study raises an important question on the stability of complex symbiotic partnerships. In intimate obligatory symbioses the evolutionary interests of both partners are often identical and what is good for one is also good for the other. This is the case of several insects that feed on poor diets like phloem and xylem sap, and which carry vertically-transmitted symbionts that provide essential nutrients. Molecular phylogenetic studies have repeatedly shown that in several insect groups transition to phloem or xylem feeding occurred at the same time these nutritional symbionts were acquired [4]. In lichens, an outstanding question is to know what was the key feature Cyphobasidium yeasts brought to the symbiosis. As suggested by the authors, these yeasts are likely to be involved in the production of secondary defensive metabolites and architectural structures, but, are these services enough to explain the diversity found in macrolichens? This paper is an appealing example of a multipartite symbiosis where the different partners share an ancient evolutionary history. References [1] Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353:488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8287 [2] Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, et al. 2010. Symbiotic Bacterium Modifies Aphid Body Color. Science 330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463 [3] Clay K. 1988. Fungal Endophytes of Grasses: A Defensive Mutualism between Plants and Fungi. Ecology 69:10–16. doi: 10.2307/1943155 [4] Moran NA. 2007. Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:8627–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611659104 | Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens | Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. | For over 140 years, lichens have been regarded as a symbiosis between a single fungus, usually an ascomycete, and a photosynthesizing partner. Other fungi have long been known to occur as occasional parasites or endophytes, but the one lichen–one ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Enric Frago | 2016-12-15 05:46:14 | View | |

25 Jun 2020

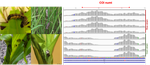

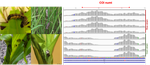

Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emmanuelle d'Alencon, Nicolas Nègre https://doi.org/10.1101/263186Speciation through selection on mitochondrial genes?Recommended by Astrid Groot based on reviews by Heiko Vogel and Sabine HaennigerWhether speciation through ecological specialization occurs has been a thriving research area ever since Mayr (1942) stated this to play a central role. In herbivorous insects, ecological specialization is most likely to happen through host plant differentiation (Funk et al. 2002). Therefore, after Dorothy Pashley had identified two host strains in the Fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, in 1988 (Pashley 1988), researchers have been trying to decipher the evolutionary history of these strains, as this seems to be a model species in which speciation is currently occurring through host plant specialization. Even though FAW is a generalist, feeding on many different host plant species (Pogue 2002) and a devastating pest in many crops, Pashley identified a so-called corn strain and a so-called rice strain in Puerto Rico. Genetically, these strains were found to differ mostly in an esterase, although later studies showed additional genetic differences and markers, mostly in the mitochondrial COI and the nuclear TPI. Recent genomic studies showed that the two strains are overall so genetically different (2% of their genome being different) that these two strains could better be called different species (Kergoat et al. 2012). So far, the most consistent differences between the strains have been their timing of mating activities at night (Schoefl et al. 2009, 2011; Haenniger et al. 2019) and hybrid incompatibilities (Dumas et al. 2015; Kost et al. 2016). Whether and to what extent host plant preference or performance contributed to the differentiation of these sympatrically occurring strains has remained unclear. References [1] Dumas, P. et al. (2015). Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host-plant variants: two host strains or two distinct species?. Genetica, 143(3), 305-316. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9829-2 | Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) | Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emm... | <p>Spodoptera frugiperda, the fall armyworm (FAW), is an important agricultural pest in the Americas and an emerging pest in sub-Saharan Africa, India, East-Asia and Australia, causing damage to major crops such as corn, sorghum and soybean. While... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Life History, Speciation | Astrid Groot | 2018-05-09 13:04:34 | View | |

12 Jul 2017

Assortment of flowering time and defense alleles in natural Arabidopsis thaliana populations suggests co-evolution between defense and vegetative lifespan strategiesGlander S, He F, Schmitz G, Witten A, Telschow A, de Meaux J 10.1101/131136Towards an integrated scenario to understand evolutionary patterns in A. thalianaRecommended by Xavier Picó based on reviews by Rafa Rubio de Casas and Xavier PicóNobody can ignore that a full understanding of evolution requires an integrated approach from both conceptual and methodological viewpoints. Although some life-history traits, e.g. flowering time, have long been receiving more attention than others, in many cases because the former are more workable than the latter, we must acknowledge that our comprehension about how evolution works is strongly biased and limited. In the Arabidopsis community, such an integration is making good progress as an increasing number of research groups worldwide are changing the way in which evolution is put to the test. This manuscript [1] is a good example of that as the authors raise an important issue in evolutionary biology by combining gene expression and flowering time data from different sources. In particular, the authors explore how variation in flowering time, which determines lifespan, and host immunity defenses co-vary, which is interpreted in terms of co-evolution between the two traits. Interestingly, the authors go beyond that pattern by separating lifespan-dependent from lifespan–independent defense genes, and by showing that defense genes with variants known to impact fitness in the field are among the genes whose expression co-varies most strongly with flowering time. Finally, these results are supported by a simple mathematical model indicating that such a relationship can also be expected theoretically. Overall, the readers will find many conceptual and methodological elements of interest in this manuscript. The idea that evolution is better understood under the scope of life history variation is really exciting and challenging, and in my opinion on the right track for disentangling the inherent complexities of evolutionary research. However, only when we face complexity, we also face its costs and burdens. In this particular case, the well-known co-variation between seed dormancy and flowering time is a missing piece, as well as the identification of (variation in) putative selective pressures accounting for the co-evolution between defense mechanisms and life history (seed dormancy vs. flowering time) along environmental gradients. More intellectual, technical and methodological challenges that with no doubt are totally worth it. Reference [1] Glander S, He F, Schmitz G, Witten A, Telschow A, de Meaux J. 2017. Assortment of flowering time and defense alleles in natural Arabidopsis thaliana populations suggests co-evolution between defense and vegetative lifespan strategies. bioRxiv ver.1 of June 19, 2017. doi: 10.1101/131136 | Assortment of flowering time and defense alleles in natural Arabidopsis thaliana populations suggests co-evolution between defense and vegetative lifespan strategies | Glander S, He F, Schmitz G, Witten A, Telschow A, de Meaux J | The selective impact of pathogen epidemics on host defenses can be strong but remains transient. By contrast, life-history shifts can durably and continuously modify the balance between costs and benefits of immunity, which arbitrates the evolutio... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Life History, Phenotypic Plasticity, Quantitative Genetics, Species interactions | Xavier Picó | Sophie Karrenberg, Rafa Rubio de Casas, Xavier Picó | 2017-06-21 10:57:14 | View |

24 Oct 2022

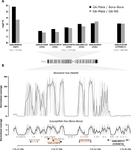

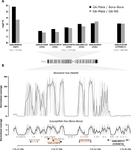

Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscuraAndres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.03.479001The other side of the evolution of heat tolerance: correlated responses in metabolism and life-history traitsRecommended by Inês Fragata and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding how species respond to environmental changes is becoming increasingly important in order to predict the future of biodiversity and species distributions under current global warming conditions (Rezende 2020; Bennett et al 2021). Two key factors to take into account in these predictions are the tolerance of organisms to heat stress and subsequently how they adapt to increasingly warmer temperatures. Coupled with this, one important factor that is often overlooked when addressing the evolution of thermal tolerance, is the correlated responses in traits that are important to fitness, such as life histories, behavior and the underlying metabolic processes. The rate and intensity of the thermal stress are expected to be major factors in shaping the evolution of heat tolerance and correlated responses in other traits. For instance, lower rates of thermal stress are predicted to select for individuals with a slower metabolism (Santos et al 2012), whereas low metabolism is expected to lead to a lower reproductive rate (Dammhahn et al 2018). To quantify the importance of the rate and intensity of thermal stress on the evolutionary response of heat tolerance and correlated response in behavior, Mesas et al (2021) performed experimental evolution in Drosophila subobscura using selective regimes with slow or fast ramping protocols. Whereas both regimes showed increased heat tolerance with similar evolutionary rates, the correlated responses in thermal performance curves for locomotor behavior differed between selection regimes. These findings suggest that thermal rate and intensity may shape the evolution of correlated responses in other traits, urging the need to understand possible correlated responses at relevant levels such as life history and metabolism. In the present contribution, Mesas and Castañeda (2022) investigate whether the disparity in thermal performance curves observed in the previous experiment (Mesas et al 2021) could be explained by differences in metabolic energy production and consumption, and how this correlated with the reproductive output (fecundity and viability). Overall, the authors show some evidence for lowered enzyme activity and increased performance in life-history traits, particularly for the slow-ramping selected flies. Specifically, the authors observe a reduction in glucose metabolism and increased viability when evolving under slow ramping stress. Interestingly, both regimes show a general increase in fecundity, suggesting that adaptation to these higher temperatures is not costly (for reproduction) in the ancestral environment. The evidence for a somewhat lower metabolism in the slow-ramping lines suggests the evolution of a slow “pace of life”. The “pace of life” concept tries to bridge variation across several levels namely metabolism, physiology, behavior and life history, with low “pace of life” organisms presenting lower metabolic rates, later reproduction and higher longevity than fast “pace of life” organisms (Dammhahn et al 2018, Tuzun & Stocks 2022). As the authors state there is not a clear-cut association with the expectations of the pace of life hypothesis since there was evidence for increased reproductive output under both selection intensity regimes. This suggests that, given sufficient trait genetic variance, positively correlated responses may emerge during some stages of thermal evolution. As fecundity estimates in this study were focussed on early life, the possibility of a decrease in the cumulative reproductive output of the selected flies, even under benign conditions, cannot be excluded. This would help explain the apparent paradox of increased fecundity in selected lines. In this context, it would also be interesting to explore the variation in reproductive output at different temperatures, i.e to obtain thermal performance curves for life histories. Mesas and Castañeda (2022) raise important questions to pursue in the future and contribute to the growing evidence that, in order to predict the distribution of ectothermic species under current global warming conditions, we need to expand beyond determining the physiological thermal limits of each organism (Parratt et al 2021). Ultimately, integrating metabolic, life-history and behavioral changes during evolution under different thermal stresses within a coherent framework is key to developing better predictions of temperature effects on natural populations. Bennett, J.M., Sunday, J., Calosi, P. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat Commun 12, 1198 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21263-8 Dammhahn, M., Dingemanse, N.J., Niemelä, P.T. et al. Pace-of-life syndromes: a framework for the adaptive integration of behaviour, physiology and life history. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72, 62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2473-y Mesas, A, Jaramillo, A, Castañeda, LE. Experimental evolution on heat tolerance and thermal performance curves under contrasting thermal selection in Drosophila subobscura. J Evol Biol 34, 767– 778 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13777 Parratt, S.R., Walsh, B.S., Metelmann, S. et al. Temperatures that sterilize males better match global species distributions than lethal temperatures. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 481–484 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01047-0 Santos, M, Castañeda, LE, Rezende, EL Keeping pace with climate change: what is wrong with the evolutionary potential of upper thermal limits? Ecology and evolution, 2(11), 2866-2880 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.385 Tüzün, N, Stoks, R. A fast pace-of-life is traded off against a high thermal performance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1972), 20212414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.2414 Rezende, EL, Bozinovic, F, Szilágyi, A, Santos, M. Predicting temperature mortality and selection in natural Drosophila populations. Science, 369(6508), 1242-1245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9287 | Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscura | Andres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda | <p>Adaptations to warming conditions exhibited by ectotherms include increasing heat tolerance but also metabolic changes to reduce maintenance costs (metabolic depression), which can allow them to redistribute the energy surplus to biological fun... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Inês Fragata | 2022-02-08 01:05:50 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasitesEva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/621581Trade-offs in fitness components and ecological source-sink dynamics affect host specialisation in two parasites of Artemia shrimpsRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin

Ecological specialisation, especially among parasites infecting a set of host species, is ubiquitous in nature. Host specialisation can be understood as resulting from trade-offs in parasite infectivity, virulence and growth. However, it is not well understood how variation in these trade-offs shapes the overall fitness trade-off a parasite faces when adapting to multiple hosts. For instance, it is not clear whether a strong trade-off in one fitness component may sufficiently constrain the evolution of a generalist parasite despite weak trade-offs in other components. A second mechanism explaining variation in specialisation among species is habitat availability and quality. Rare habitats or habitats that act as ecological sinks will not allow a species to persist and adapt, preventing a generalist phenotype to evolve. Understanding the prevalence of those mechanisms in natural systems is crucial to understand the emergence and maintenance of host specialisation, and biodiversity in general. References [1] Lievens, E.J.P., Michalakis, Y. and Lenormand, T. (2019). Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites. bioRxiv, 621581, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/621581 | Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites | Eva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand | <p>The evolution of host specialization has been studied intensively, yet it is still often difficult to determine why parasites do not evolve broader niches – in particular when the available hosts are closely related and ecologically similar. He... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Frédéric Guillaume | 2019-05-13 13:44:34 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

05 May 2020

Meta-population structure and the evolutionary transition to multicellularityCaroline J Rose, Katrin Hammerschmidt, Yuriy Pichugin and Paul B Rainey https://doi.org/10.1101/407163The ecology of evolutionary transitions to multicellularityRecommended by Dustin Brisson based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe evolutionary transition to multicellular life from free-living, single-celled ancestors has occurred independently in multiple lineages [1-5]. This evolutionary transition to cooperative group living can be difficult to explain given the fitness advantages enjoyed by the non-cooperative, single-celled organisms that still numerically dominate life on earth [1,6,7]. Although several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the transition to multicellularity, a common theme is the abatement of the efficacy of natural selection among the single cells during the free-living stage and the promotion of the efficacy of selection among groups of cells during the cooperative stage, an argument reminiscent of those from George Williams’ seminal book [8,9]. The evolution of life cycles appears to be a key step in the transition to multicellularity as it can align fitness advantages of the single-celled 'reproductive' stage with that of the cooperative 'organismal' stage [9-12]. That is, the evolution of life cycles allows natural selection to operate over timescales longer than that of the doubling time of the free-living cells [13]. Despite the importance of this issue, identifying the range of ecological conditions that reduce the importance of natural selection at the single-celled, free-living stage and increase the importance of selection among groups of cooperating cells has not been addressed empirically. References [1] Maynard Smith, J. and Szathmáry, E. (1995). The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford, UK: Freeman. p 346. | Meta-population structure and the evolutionary transition to multicellularity | Caroline J Rose, Katrin Hammerschmidt, Yuriy Pichugin and Paul B Rainey | <p>The evolutionary transition to multicellularity has occurred on numerous occasions, but transitions to complex life forms are rare. While the reasons are unclear, relevant factors include the intensity of within- versus between-group selection ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Experimental Evolution | Dustin Brisson | 2019-04-04 12:26:36 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

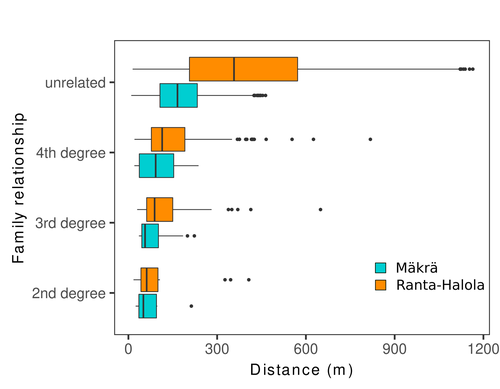

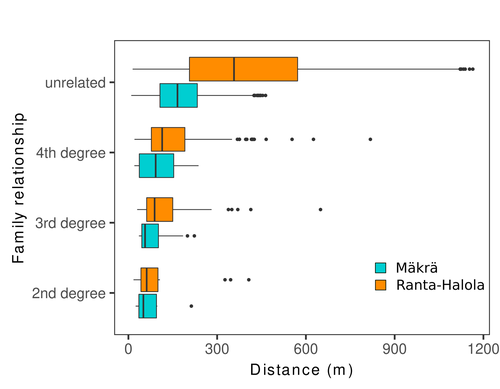

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

23 Apr 2020

How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridisJulien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Estoup, Benoit Facon https://doi.org/10.1101/849968Selection on a single trait does not recapitulate the evolution of life-history traits seen during an invasionRecommended by Inês Fragata and Ben Phillips based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersBiological invasions are natural experiments, and often show that evolution can affect dynamics in important ways [1-3]. While we often think of invasions as a conservation problem stemming from anthropogenic introductions [4,5], biological invasions are much more commonplace than this, including phenomena as diverse as natural range shifts, the spread of novel pathogens, and the growth of tumors. A major question across all these settings is which set of traits determine the ability of a population to invade new space [6,7]. Traits such as: increased growth or reproductive rate, dispersal ability and ability to defend from predation often show large evolutionary shifts across invasion history [1,6,8]. Are such multi-trait shifts driven by selection on multiple traits, or a correlated response by multiple traits to selection on one? Resolving this question is important for both theoretical and practical reasons [9,10]. But despite the importance of this issue, it is not easy to perform the necessary manipulative experiments [9]. References [1] Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S. et al. (2001). The population biology of invasive species. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 32(1), 305-332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 | How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridis | Julien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Est... | <p>Experiments comparing native to introduced populations or distinct introduced populations to each other show that phenotypic evolution is common and often involves a suit of interacting phenotypic traits. We define such sets of traits that evol... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Inês Fragata | 2019-11-29 07:07:00 | View | |

05 Nov 2020

A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detectionJulien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Philippe David https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741Identification of a gene cluster amplification associated with organophosphate insecticide resistance: from the diversity of the resistance allele complex to an efficient field detection assayRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Diego Ayala and 2 anonymous reviewersThe emergence and spread of insecticide resistance compromises the efficiency of insecticides as prevention tool against the transmission of insect-transmitted diseases (Moyes et al. 2017). In this context, the understanding of the genetic mechanisms of resistance and the way resistant alleles spread in insect populations is necessary and important to envision resistance management policies. A common and important mechanism of insecticide resistance is gene amplification and in particular amplification of insecticide detoxification genes, which leads to the overexpression of these genes (Bass & Field, 2011). Cattel and coauthors (2020) adopt a combination of experimental approaches to study the role of gene amplification in resistance to organophosphate insecticides in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and its occurrence in populations of South East Asia and to develop a molecular test to track resistance alleles. References Bass C, Field LM (2011) Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Management Science, 67, 886–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2189 | A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection | Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Phil... | <p>By altering gene expression and creating paralogs, genomic amplifications represent a key component of short-term adaptive processes. In insects, the use of insecticides can select gene amplifications causing an increased expression of detoxifi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2020-06-09 13:27:18 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer