Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance lociMetzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. 10.1111/evo.12854Evidence of epistasis provides further support to the Red Queen theory of host-parasite coevolutionRecommended by Adele Mennerat and Thierry LefèvreAccording to the Red Queen theory of antagonistic host-parasite coevolution, adaptation of parasites to the most common host genotype results in negative frequency-dependent selection whereby rare host genotypes are favoured. Assuming that host resistance relies on a genetic host-parasite (mis)match involving several linked loci, then recombination appears as much more efficient than parthenogenesis in generating new resistant host genotypes. This has long been proposed to explain one of the biggest so-called paradoxes in evolutionary biology, i.e. the maintenance of recombination despite its twofold cost. Evidence from various study systems indicates that successful infection (and hence host resistance) depends on a genetic match between the parasite’s and the host’s genotype via molecular interactions involving elicitor/receptor mechanisms. However the key assumption of epistasis, i.e. that this genetic host-parasite match involves several linked resistance loci, remained unsupported so far. Metzger and coauthors [1] now provide empirical support for it. Daphnia magna can reproduce both sexually and clonally and their well-studied interaction with Pasteuria ramosa makes them an excellent model system to investigate the genetics of host resistance. D. magna hosts were found to be either resistant (complete lack of attachment of parasite spores to the host’s foregut) or susceptible (full attachment). In this study the authors carried out an elegant Mendelian genetic investigation by performing multiple crosses between four host genotypes differing in their resistance to two different parasite isolates [1]. Their results show that resistance of D. magna to each of the two P. ramosa isolates relies on Mendelian inheritance at two loci that are linked (A and B), each of them having two alleles with dominant resistance; furthermore resistance to one parasite isolate confers susceptibility to the other. They also show that a third locus appears to confer double resistance (C), but that even double resistant hosts remain susceptible to other parasite isolates, and hence that universal host resistance is lacking – all of this supporting the Red Queen theory. This paper demonstrates with a high level of clarity that host resistance is governed by multiple linked loci. The assumption of epistasis between resistance loci is supported, which makes it possible for sexual recombination to be maintained by antagonistic host-parasite coevolution. Reference [1] Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. 2016. The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci. Evolution 70:480-487. doi: 10.1111/evo.12854 | The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci | Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. | A popular theory explaining the maintenance of genetic recombination (sex) is the Red Queen Theory. This theory revolves around the idea that time-lagged negative frequency-dependent selection by parasites favors rare host genotypes generated thro... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Adele Mennerat | 2016-12-14 13:58:53 | View | |

03 May 2020

When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue?Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl https://doi.org/10.1101/622142Reconciling the upsides and downsides of migration for evolutionary rescueRecommended by Claudia Bank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolutionary response of populations to changing or novel environments is a topic that unites the interests of evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and biomedical researchers [1]. A prominent phenomenon in this research area is evolutionary rescue, whereby a population that is otherwise doomed to extinction survives due to the spread of new or pre-existing mutations that are beneficial in the new environment. Scenarios of evolutionary rescue require a specific set of parameters: the absolute growth rate has to be negative before the rescue mechanism spreads, upon which the growth rate becomes positive. However, potential examples of its relevance exist (e.g., [2]). From a theoretical point of view, the technical challenge but also the beauty of evolutionary rescue models is that they combine the study of population dynamics (i.e., changes in the size of populations) and population genetics (i.e., changes in the frequencies in the population). Together, the potential relevance of evolutionary rescue in nature and the models' theoretical appeal has resulted in a suite of modeling studies on the subject in recent years. References [1] Bell, G. (2017). Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48(1), 605-627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue? | Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl | <p>Experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the impact of gene flow on the probability of evolutionary rescue in structured habitats. Mathematical modelling and simulations of evolutionary rescue in spatially or otherwise structured p... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Claudia Bank | 2019-05-22 11:12:13 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

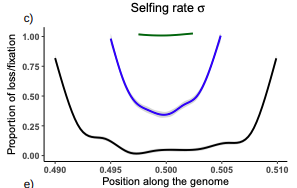

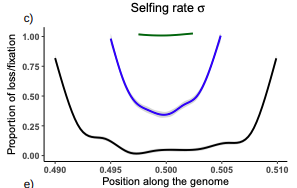

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewerMost mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradientAndrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine https://doi.org/10.1101/236646One (more) step towards a dynamic view of the Latitudinal Diversity GradientRecommended by Joaquín Hortal and Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers

The Latitudinal Diversity Gradient (LDG) has fascinated natural historians, ecologists and evolutionary biologists ever since [1] described it about 200 years ago [2]. Despite such interest, agreement on the origin and nature of this gradient has been elusive. Several tens of hypotheses and models have been put forward as explanations for the LDG [2-3], that can be grouped in ecological, evolutionary and historical explanations [4] (see also [5]). These explanations can be reduced to no less than 26 hypotheses, which account for variations in ecological limits for the establishment of progressively larger assemblages, diversification rates, and time for species accumulation [5]. Besides that, although in general the tropics hold more species, different taxa show different shapes and rates of spatial variation [6], and a considerable number of groups show reverse patterns, with richer assemblages in cold temperate regions (see e.g. [7-9]). References | Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient | Andrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine | <p>Biodiversity currently peaks at the equator, decreasing toward the poles. Growing fossil evidence suggest that this hump-shaped latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG) has not been persistent through time, with similar species diversity across lat... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Joaquín Hortal | 2017-12-20 14:58:01 | View | |

24 Aug 2022

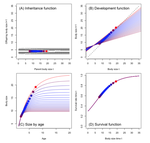

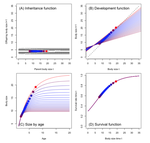

Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body sizeTim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952A population biological modeling approach for life history and body size evolutionRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 2 anonymous reviewersBody size evolution is a central theme in evolutionary biology. Particularly the question of when and how smaller body sizes can evolve continues to interest evolutionary ecologists, because most life history models, and the empirical evidence, document that large body size is favoured by natural and sexual selection in most (even small) organisms and environments at most times. How, then, can such a large range of body size and life history syndromes evolve and coexist in nature? The paper by Coulson et al. lifts this question to the level of the population, a relatively novel approach using so-called integral projection (simulation) models (IPMs) (as opposed to individual-based or game theoretical models). As is well outlined by (anonymous) Reviewer 1, and following earlier papers spearheading this approach in other life history contexts, the authors use the well-known carrying capacity (K) of population biology as the ultimate fitness parameter to be maximized or optimized (rather than body size per se), to ultimately identify factors and conditions promoting the evolution of extreme body sizes in nature. They vary (individual or population) size-structured growth trajectories to observe age and size at maturity, surivorship and fecundity/fertility schedules upon evaluating K (see their Fig. 1). Importantly, trade-offs are introduced via density-dependence, either for adult reproduction or for juvenile survival, in two (of several conceivable) basic scenarios (see their Table 2). All other relevant standard life history variables (see their Table 1) are assumed density-independent, held constant or zero (as e.g. the heritability of body size). The authors obtain evidence for disruptive selection on body size in both scenarios, with small size and a fast life history evolving below a threshold size at maturity (at the lowest K) and large size and a slow life history beyond this threshold (see their Fig. 2). Which strategy wins ultimately depends on the fitness benefits of delaying sexual maturity (at larger size and longer lifespan) at the adult stage relative to the preceeding juvenile mortality costs, in agreement with classic life history theory (Roff 1992, Stearns 1992). The modeling approach can be altered and refined to be applied to other key life history parameters and environments. These results can ultimately explain the evolution of smaller body sizes from large body sizes, or vice versa, and their corresponding life history syndromes, depending on the precise environmental circumstances. All reviewers agreed that the approach taken is technically sound (as far as it could be evaluated), and that the results are interesting and worthy of publication. In a first round of reviews various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers. The new version was substantially changed by the authors in response, to the extent that it now is a quite different but much clearer paper with a clear message palatable for the general reader. The writing is now to the point, the paper's focus becomes clear in the Introduction, Methods & Results are much less technical, the Figures illustrative, and the descriptions and interpretations in the Discussion are easy to follow. In general any reader may of course question the choice and realism of the scenarios and underlying assumptions chosen by the authors for simplicity and clarity, for instance no heritability of body size and no cost of reproduction (other than mortality). But this is always the case in modeling work, and the authors acknowledge and in fact suggest concrete extensions and expansions of their approach in the Discussion. References Coulson T., Felmy A., Potter T., Passoni G., Montgomery R.A., Gaillard J.-M., Hudson P.J., Travis J., Bassar R.D., Tuljapurkar S., Marshall D.J., Clegg S.M. (2022) Density-dependent environments can select for extremes of body size. bioRxiv, 2022.02.17.480952, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952 | Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body size | Tim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg | <p>Body size variation is an enigma. We do not understand why species achieve the sizes they do, and this means we also do not understand the circumstances under which gigantism or dwarfism is selected. We develop size-structured integral projecti... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2022-02-21 07:59:04 | View | |

06 Mar 2023

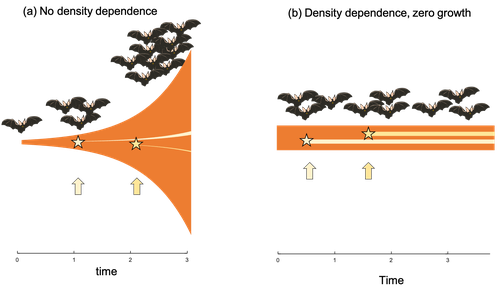

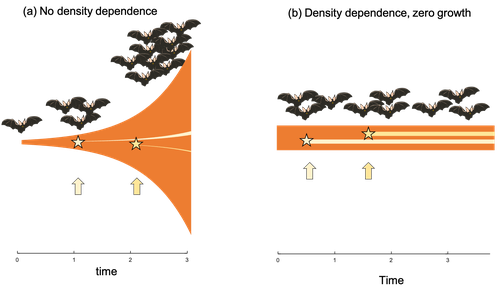

Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexedCharlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060Getting old gracefully, and risk of dying before getting there: a new guide to theory on extrinsic mortality and senescenceRecommended by Sinead English and Shinichi Nakagawa based on reviews by Nicole Walasek and 1 anonymous reviewerWhy is there such variation across species and populations in the rate at which individuals show wear and tear as they get older? Several compelling theoretical explanations have been developed on the conditions under which selection allows for or prevents senescence; a notable one being that proposed by George C Williams in 1957 based on the idea of antagonistic pleiotropy (Williams, 1957). One of the testable predictions of this theory is that, in populations where adults experience higher mortality, senescence is expected to be faster. This is one of the most influential predictions of the paper, being intuitive (when individuals are less likely to survive to later age classes, we expect weakened selection on traits that would avoid senescence in these classes), and fitting with ‘live fast, die young’ life history framing. As such, it has been widely incorporated into how we think about the evolution of senescence and has received considerable support in comparative studies across species and populations. However, it would be misleading to sit back at this point and think we have ‘solved’ the problem of understanding variation in senescence, and how this is linked with mortality. It turns out that the Williams 1957 paper is hotly contested by theoreticians: for the past 30 years – with increasing focus in the last 4 years – a growing body of models and opinion pieces have proposed flaws in the paper itself and in how it has been interpreted (Abrams, 1993; André and Rousset, 2020; Day and Abrams, 2020; Moorad et al., 2019). Central to several of these critiques is that explicit consideration of density dependence (not considered in Williams’ original paper) changes the conditions under which his predictions hold. A new preprint by de Vries, Gallipaud and Kokko brings further clarity to such critiques of the original paper (Vries et al., 2023). Beyond just continuing the tradition of critiquing Williams’ prediction, however, de Vries et al. provide a clear guide that is accessible to non-theoreticians about the issues with William’s prediction, and the way in which density dependence and how it operates can change when we expect senescence to occur. Rather than reiterate their points here, we suggest a close reading of the paper itself, along with an excellent overview of the paper in a recent blog by Daniel Nettle (Nettle, 2022). In brief, the paper starts by synthesizing earlier theoretical and empirical studies on the topic and presenting a very simple model to highlight how – in the absence of density dependence – Williams’ prediction does not hold because of the unregulated population growth, which is necessarily higher when there is low mortality. As a result, for a lineage with low mortality, any fitness advantage of placing offspring into the lineage later (i.e. selection for reduced senescence) is exactly cancelled out by the fact that earlier-produced offspring have higher fitness returns. They then present a more complex framework, which incorporates realistic mortality distributions, trade-offs between survival and reproduction, and use a series of 10 scenarios of density dependence (and whether this acts on survival or fecundity, and also whether it depends on a threshold or stochastic, or exerts continuing pressure on the trait) to explore selection on fitness-associated traits with age depending on extrinsic mortality. This then generates a range of results for when the Williams prediction holds, when there is no link between mortality and senescence, and when there is an ‘anti-Williams’ result – i.e., where senescence is slower when there is a high mortality. As has been shown in earlier studies, density dependence and how it operates matters, and Williams’ prediction holds most when density dependence affects juvenile age classes (in their model, when adults are less likely to produce them – i.e. there is density dependence on fecundity; or when there is less recruitment into the adult population due to, for example, competition among juveniles). So, perhaps we are now at a point where we can lay to rest the debate on the issues specifically with Williams’ original paper, and instead consider more broadly the key factors to measure when predicting patterns of senescence, and what is tangible for empiricists to quantify in their studies. Here, de Vries et al. provide some helpful insights both into the limitations of their approach and what modelling should be done moving forward, and into how we can link existing studies (for example comparing senescence among populations with varying predation pressure) to the theoretical predictions. At the heart of the latter is understanding the mechanism of density-dependent regulation – does it affect survival or fecundity, which age classes are most sensitive, and how do key traits depend on density? – and this is often difficult to measure in field studies. And from all this we can learn that even very intuitive and extensively discussed concepts in biology do not always have as firm theoretical underpinnings as assumed, and – as should not be surprising – biology is complex and rather than one clear pattern being predicted, this can depend on a multitude of factors. REFERENCES Abrams PA (1993) Does increased mortality favor the evolution of more rapid senescence? Evolution, 47, 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01241.x André J-B, Rousset F (2020) Does extrinsic mortality accelerate the pace of life? A bare-bones approach. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41, 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.03.002 Day T, Abrams PA (2020) Density Dependence, Senescence, and Williams’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 300–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.11.005 Moorad J, Promislow D, Silvertown J (2019) Evolutionary Ecology of Senescence and a Reassessment of Williams’ ‘Extrinsic Mortality’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.02.006 Nettle AD (2022) Live fast and die young (maybe). https://www.danielnettle.org.uk/2022/02/18/live-fast-and-die-young-maybe/ (accessed 2.27.23). de Vries C, Galipaud M, Kokko H (2023) Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed. bioRxiv, 2022.01.27.478060, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060 Williams GC (1957) Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution, 11, 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1957.tb02911.x | Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed | Charlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">Do environments or species traits that lower the mortality of individuals create selection for delaying senescence? Reading the literature creates an impression that mathematically oriented biologists cannot agree o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Sinead English | 2022-08-26 14:30:16 | View | |

18 Jan 2023

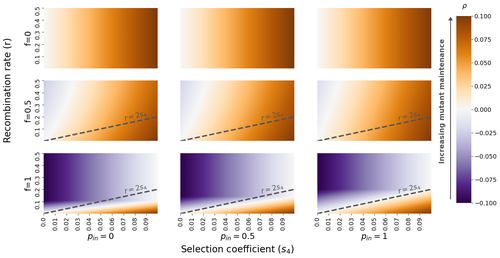

The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfingEmilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119Maintenance of deleterious mutations and recombination suppression near mating-type loci under selfingRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe causes and consequences of the evolution of sexual reproduction are a major topic in evolutionary biology. With advances in sequencing technology, it becomes possible to compare sexual chromosomes across species and infer the neutral and selective processes shaping polymorphism at these chromosomes. Most sex and mating-type chromosomes exhibit an absence of recombination in large genomic regions around the animal, plant or fungal sex-determining genes. This suppression of recombination likely occurred in several time steps generating stepwise increasing genomic regions starting around the sex-determining genes. This mechanism generates so-called evolutionary strata of differentiation between sex chromosomes (Nicolas et al., 2004, Bergero and Charlesworth, 2009, Hartmann et al. 2021). The evolution of extended regions of recombination suppression is also documented on mating-type chromosomes in fungi (Hartmann et al., 2021) and around supergenes (Yan et al., 2020, Jay et al., 2021). The exact reason and evolutionary mechanisms for this phenomenon are still, however, debated. Two hypotheses are proposed: 1) sexual antagonism (Charlesworth et al., 2005), which, nevertheless, does explain the observed occurrence of the evolutionary strata, and 2) the sheltering of deleterious alleles by inversions carrying a lower load than average in the population (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004). In the latter, the mechanism is as follows. A genetic inversion or a suppressor of recombination in cis may exhibit some overdominance behaviour. The inversion exhibiting less recessive deleterious mutations (compared to others at the same locus) may increase in frequency, before at higher frequency occurring at the homozygous state, expressing its genetic load. However, the inversion may never be at the homozygous state if it is genetically linked to a gene in a permanently heterozygous state. The inversion can then be advantageous and may reach fixation at the sex chromosome (Charlesworth and Wall, 1999, Antonovics and Abrams, 2004, Jay et al., 2022). These selective mechanisms promote thus the suppression of recombination around the sex-determining gene, and recessive deleterious mutations are permanently sheltered. This hypothesis is corroborated by the sheltering of deleterious mutations observed around loci under balancing selection (Llaurens et al. 2009, Lenz et al. 2016) and around mating-type genes in fungi and supergenes (Jay et al. 2021, Jay et al., 2022). In this present theoretical study, Tezenas et al. (2022) analyse how linkage to a necessarily heterozygous fungal mating type locus influences the persistence/extinction time of a new mutation at a second selected locus. This mutation can either be deleterious and recessive, or overdominant. There is arbitrary linkage between the two loci, and sexual reproduction occurs either between 1) gametes of different individuals (outcrossing), or 2) by selfing with gametes originating from the same (intra-tetrad) or different (inter-tetrad) tetrads produced by that individual. Note, here, that the mating-type gene does not prevent selfing. The authors study the initial stochastic dynamics of the mutation using a multi-type branching process (and simulations when analytical results cannot be obtained) to compute the extinction time of the deleterious mutation. The main result is that the presence of a mating-type locus always decreases the purging probability and increases the purging time of the mutations under selfing. Ultimately, deleterious mutations can indeed accumulate near the mating-type locus over evolutionary time scales. In a nutshell, high selfing or high intra-tetrad mating do increase the sheltering effect of the mating-type locus. In effect, the outcome of sheltering of deleterious mutations depends on two opposing mechanisms: 1) a higher selfing rate induces a greater production of homozygotes and an increased effect of the purging of deleterious mutations, while 2) a higher intra-tetrad selfing rate (or linkage with the mating-type locus) generates heterozygotes which have a small genetic load (and are favoured). The authors also show that rare events of extremely long maintenance of deleterious mutations can occur. The authors conclude by highlighting the manifold effect of selfing which reduces the effective population size and thus impairs the efficiency of selection and increases the mutational load, while also favouring the purge of deleterious homozygous mutations. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of studying the maintenance and accumulation of deleterious mutations in the vicinity of heterozygous loci (e.g. under balancing selection) in selfing species. References Antonovics J, Abrams JY (2004) Intratetrad Mating and the Evolution of Linkage Relationships. Evolution, 58, 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00403.x Bergero R, Charlesworth D (2009) The evolution of restricted recombination in sex chromosomes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.010 Charlesworth D, Morgan MT, Charlesworth B (1990) Inbreeding Depression, Genetic Load, and the Evolution of Outcrossing Rates in a Multilocus System with No Linkage. Evolution, 44, 1469–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03839.x Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G (2005) Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity, 95, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697 Charlesworth B, Wall JD (1999) Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo–X and neo–Y sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0603 Hartmann FE, Duhamel M, Carpentier F, Hood ME, Foulongne-Oriol M, Silar P, Malagnac F, Grognet P, Giraud T (2021) Recombination suppression and evolutionary strata around mating-type loci in fungi: documenting patterns and understanding evolutionary and mechanistic causes. New Phytologist, 229, 2470–2491. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17039 Jay P, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Bastide H, Parrinello H, Llaurens V, Joron M (2021) Mutation load at a mimicry supergene sheds new light on the evolution of inversion polymorphisms. Nature Genetics, 53, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00771-1 Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, Giraud T (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 Lenz TL, Spirin V, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR (2016) Excess of Deleterious Mutations around HLA Genes Reveals Evolutionary Cost of Balancing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 2555–2564. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw127 Llaurens V, Gonthier L, Billiard S (2009) The Sheltered Genetic Load Linked to the S Locus in Plants: New Insights From Theoretical and Empirical Approaches in Sporophytic Self-Incompatibility. Genetics, 183, 1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.102707 Nicolas M, Marais G, Hykelova V, Janousek B, Laporte V, Vyskot B, Mouchiroud D, Negrutiu I, Charlesworth D, Monéger F (2004) A Gradual Process of Recombination Restriction in the Evolutionary History of the Sex Chromosomes in Dioecious Plants. PLOS Biology, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 Tezenas E, Giraud T, Véber A, Billiard S (2022) The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing. bioRxiv, 2022.10.07.511119, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511119 Yan Z, Martin SH, Gotzek D, Arsenault SV, Duchen P, Helleu Q, Riba-Grognuz O, Hunt BG, Salamin N, Shoemaker D, Ross KG, Keller L (2020) Evolution of a supergene that regulates a trans-species social polymorphism. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1081-1 | The fate of recessive deleterious or overdominant mutations near mating-type loci under partial selfing | Emilie Tezenas, Tatiana Giraud, Amandine Veber, Sylvain Billiard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Large regions of suppressed recombination having extended over time occur in many organisms around genes involved in mating compatibility (sex-determining or mating-type genes). The sheltering of deleterious alleles... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Aurelien Tellier | 2022-10-10 13:50:30 | View | |

05 Jan 2023

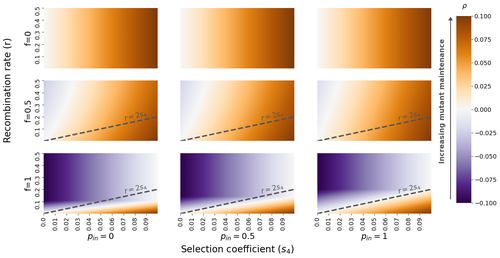

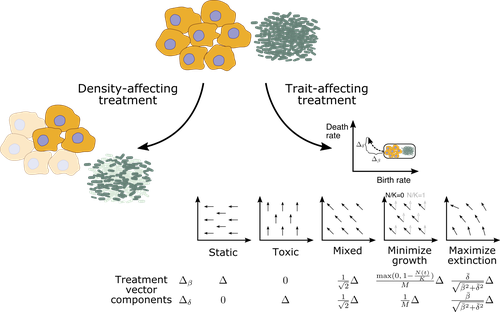

Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populationsMichael Raatz, Arne Traulsen https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570Trait trajectories in evolving populations: insights from mathematical modelsRecommended by Dominik Wodarz based on reviews by Rob Noble and 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of cells within organisms can be an important determinant of disease. This is especially clear in the emergence of tumors and cancers from the underlying healthy tissue. In the healthy state, homeostasis is maintained through complex regulatory processes that ensure a relatively constant population size of cells, which is required for tissue function. Tumor cells escape this homeostasis, resulting in uncontrolled growth and consequent disease. Disease progression is driven by further evolutionary processes within the tumor, and so is the response of tumors to therapies. Therefore, evolutionary biology is an important component required for a better understanding of carcinogenesis and the treatment of cancers. In particular, evolutionary theory helps define the principles of mutant evolution and thus to obtain a clearer picture of the determinants of tumor emergence and therapy responses. The study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] makes an important contribution in this respect. They use mathematical and computational models to investigate trait evolution in the context of evolutionary rescue, motivated by the dynamics of cancer, and also bacterial infections. This study views the establishment of tumors as cell dynamics in harsh environments, where the population is prone to extinction unless mutants emerge that increase evolutionary fitness, allowing them to expand (evolutionary rescue). The core processes of the model include growth, death, and mutations. Random mutations are assumed to give rise to cell lineages with different trait combinations, where the birth and death rates of cells can change. The resulting evolutionary trajectories are investigated in the models, and interesting new results were obtained. For example, the turnover of the population was identified as an important determinant of trait evolution. Turnover is defined as the balance between birth and death, with large rates corresponding to fast turnover and small rates to slow turnover. It was found that for fast cell turnover, a given adaptive step in the trait space results in a smaller increase in survival probability than for cell populations with slower turnover. In other words, evolutionary rescue is more difficult to achieve for fast compared to slow turnover populations. While more mutants can be produced for faster cell turnover rates, the analysis showed that this is not sufficient to overcome the barrier to the evolutionary rescue. This result implies that aggressive tumors with fast cell birth and death rates are less likely to persist and progress than tumors with lower turnover rates. This work emphasizes the importance of measuring the turnover rate in different tumors to advance our understanding of the determinants of tumor initiation and progression. The authors discuss that the well-documented heterogeneity in tumors likely also applies to cellular turnover. If a tumor consists of sub-populations with faster and slower turnover, it is possible that a slower turnover cell clone (e.g. characterized by a degree of dormancy) would enjoy a selective advantage. Another source of heterogeneity in turnover could be given by the hierarchical organization of tumors. Similar to the underlying healthy tissue, many tumors are thought to be maintained by a population of cancer stem cells, while the tumor bulk is made up of more differentiated cells. Tissue stem cells tend to be characterized by a lower turnover than progenitor or transit-amplifying cells. Depending on the assumptions about the self-renewal capacity of these different cell populations, the potential for evolutionary rescue could be different depending on the cell compartment in which the mutant emerges. This might be interesting to explore in the future. There are also implications for treatment. Two types of treatment were investigated: density-affecting treatments in which the density of cells is reduced without altering their trait parameters, and trait-affecting treatments in which the birth and/or death rates are altered. Both types of treatment were found to change the trajectories of trait adaptation, which has potentially important practical implications. Interestingly, it was found that competitive release during treatment can result in situations where after treatment cessation, the non-extinct populations recover to reach sizes that were higher than in the absence of treatment. This points towards the potential of adaptive therapy approaches, where sensitive cells are maintained to some extent to suppress resistant clones [2] competitively. In this context, it is interesting that the success of such approaches might also depend on the turnover of the tumor cell population, as shown by a recent mathematical modeling study [3]. In particular, it was found that adaptive therapy is less likely to work for slow compared to fast turnover tumors. Yet, the current study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] suggests that tumors are more likely to evolve in a slow turnover setting. While there is strong relevance of this analysis for tumor evolution, the results generated in this study have more general relevance. Besides tumors, the paper discusses applications to bacterial disease dynamics in some detail, which is also interesting to compare and contrast to evolutionary processes in cancer. Overall, this study provides insights into the dynamics of evolutionary rescue that represent valuable additions to evolutionary theory. References [1] Raatz M, Traulsen A (2023) Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.496570, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570 [2] Gatenby RA, Silva AS, Gillies RJ, Frieden BR (2009) Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 69, 4894–4903. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3658 [3] Strobl MAR, West J, Viossat Y, Damaghi M, Robertson-Tessi M, Brown JS, Gatenby RA, Maini PK, Anderson ARA (2021) Turnover Modulates the Need for a Cost of Resistance in Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 81, 1135–1147. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0806 | Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations | Michael Raatz, Arne Traulsen | <p style="text-align: justify;">When cancers or bacterial infections establish, small populations of cells have to free themselves from homoeostatic regulations that prevent their expansion. Trait evolution allows these populations to evade this r... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory | Dominik Wodarz | 2022-06-18 08:44:37 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasitesHannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259Modelling parasitoid virulence evolution with seasonalityRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers

The harm most parasites cause to their host, i.e. the virulence, is a mystery because host death often means the end of the infectious period. For obligate killer parasites, or “parasitoids”, that need to kill their host to transmit to other hosts the question is reversed. Indeed, more rapid host death means shorter generation intervals between two infections and mathematical models show that, in the simplest settings, natural selection should always favour more virulent strains (Levin and Lenski, 1983). Adding biological details to the model modifies this conclusion and, for instance, if the relationship between the infection duration and the number of parasites transmission stages produced in a host is non-linear, strains with intermediate levels of virulence can be favoured (Ebert and Weisser 1997). Other effects, such as spatial structure, could yield similar effects (Lion and van Baalen, 2007). In their study, MacDonald et al. (2021) explore another type of constraint, which is seasonality. Earlier studies, such as that by Donnelly et al. (2013) showed that this constraint can affect virulence evolution but they had focused on directly transmitted parasites. Using a mathematical model capturing the dynamics of a parasitoid, MacDonald et al. (2021) show if two main assumptions are met, namely that at the end of the season only transmission stages (or “propagules”) survive and that there is a constant decay of these propagules with time, then strains with intermediate levels of virulence are favoured. Practically, the authors use delay differential equations and an adaptive dynamics approach to identify evolutionary stable strategies. As expected, the longer the short the season length, the higher the virulence (because propagule decay matters less). The authors also identify a non-linear relationship between the variation in host development time and virulence. Generally, the larger the variation, the higher the virulence because the parasitoid has to kill its host before the end of the season. However, if the variation is too wide, some hosts become physically impossible to use for the parasite, whence a decrease in virulence. Finally, MacDonald et ali. (2021) show that the consequence of adding trade-offs between infection duration and the number of propagules produced is in line with earlier studies (Ebert and Weisser 1997). These mathematical modelling results provide testable predictions for using well-described systems in evolutionary ecology such as daphnia parasitoids, baculoviruses, or lytic phages. Reference Donnelly R, Best A, White A, Boots M (2013) Seasonality selects for more acutely virulent parasites when virulence is density dependent. Proc R Soc B, 280, 20122464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2464 Ebert D, Weisser WW (1997) Optimal killing for obligate killers: the evolution of life histories and virulence of semelparous parasites. Proc R Soc B, 264, 985–991. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0136 Levin BR, Lenski RE (1983) Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M eds. Coevolution. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 99–127. Lion S, van Baalen M (2008) Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecol. Lett., 11, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x MacDonald H, Akçay E, Brisson D (2021) Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites. bioRxiv, 2021.03.13.435259, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259 | Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites | Hannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">The traditional mechanistic trade-offs resulting in a negative correlation between transmission and virulence are the foundation of nearly all current theory on the evolution of parasite virulence. Several ecologica... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2021-03-14 13:47:33 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer