Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

19 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptationKoyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12653Megacicadas show a temperature-mediated converse Bergmann cline in body size (larger in the warmer south) but no body size difference between 13- and 17-year species pairsRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Thomas FlattPeriodical cicadas are a very prominent insect group in North America that are known for their large size, good looks, and loud sounds. However, they are probably known best to evolutionary ecologists because of their long juvenile periods of 13 or 17 years (prime numbers!), which they spend in the ground. Multiple related species living in the same area are often coordinated in emerging as adults during the same year, thereby presumably swamping any predators specialized on eating them. Reference [1] Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T. 2015. Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12653 | Geographic body size variation in the periodical cicadas Magicicada: implications for life cycle divergence and local adaptation | Koyama T, Ito H, Kakishima S, Yoshimura J, Cooley JR, Simon C, Sota T | <p>Seven species in three species groups (Decim, Cassini and Decula) of periodical cicadas (*Magicicada*) occupy a wide latitudinal range in the eastern United States. To clarify how adult body size, a key trait affecting fitness, varies geographi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Macroevolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Speciation | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2016-12-19 10:39:22 | View | |

17 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling studyHerbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vew028Predicting HIV virulence evolution in response to widespread treatmentRecommended by Samuel Alizon and Roger Kouyos and Roger Kouyos

It is a classical result in the virulence evolution literature that treatments decreasing parasite replication within the host should select for higher replication rates, thus driving increased levels of virulence if the two are correlated. There is some evidence for this in vitro but very little in the field. HIV infections in humans offer a unique opportunity to go beyond the simple predictions that treatments should favour more virulent strains because many details of this host-parasite system are known, especially the link between set-point virus load, transmission rate and virulence. To tackle this question, Herbeck et al. [1] used a detailed individual-based model. This is original because it allows them to integrate existing knowledge from the epidemiology and evolution of HIV (e.g. recent estimates of the ‘heritability’ of set-point virus load from one infection to the next). This detailed model allows them to formulate predictions regarding the effect of different treatment policies; especially regarding the current policy switch away from treatment initiation based on CD4 counts towards universal treatment. The results show that, perhaps as expected from the theory, treatments based on the level of remaining host target cells (CD4 T cells) do not affect virulence evolution because they do not strongly affect the virulence level that maximizes HIV’s transmission potential. However, early treatments can lead to moderate increase in virulence within several years if coverage is high enough. These results seem quite robust to variation of all the parameters in realistic ranges. The great step forward in this model is the ability to obtain quantitative prediction regarding how a virus may evolve in response to public health policies. Here the main conclusion is that given our current knowledge in HIV biology, the risk of virulence evolution is perhaps more limited than expected from a direct application of virulence evolution model. Interestingly, the authors also conclude that recently observed increased in HIV virulence [2-3] cannot be explained by the impact of antiretroviral therapy alone; which raises the question about the main mechanism behind this increase. Finally, the authors make the interesting suggestion that “changing virulence is amenable to being monitored alongside transmitted drug resistance in sentinel surveillance”. References [1] Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C. 2016. Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study. Virus Evolution 2:vew028. doi: 10.1093/ve/vew028 [2] Herbeck JT, Müller V, Maust BS, Ledergerber B, Torti C, et al. 2012. Is the virulence of HIV changing? A meta-analysis of trends in prognostic markers of HIV disease progression and transmission. AIDS 26:193-205. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834db418 [3] Pantazis N, Porter K, Costagliola D, De Luca A, Ghosn J, et al. 2014. Temporal trends in prognostic markers of HIV-1 virulence and transmissibility: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 1:e119-26. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(14)00002-2 | Evolution of HIV virulence in response to widespread scale up of antiretroviral therapy: a modeling study | Herbeck JT, Mittler JE, Gottlieb GS, Goodreau SM, Murphy JT, Cori A, Pickles M, Fraser C | <p>There are global increases in the use of HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART), guided by clinical benefits of early ART initiation and the efficacy of treatment as prevention of transmission. Separately, it has been shown theoretically and empirica... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Samuel Alizon | 2016-12-16 20:54:08 | View | |

16 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature.André J-B, Nolfi S https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32785Simulated robots and the evolution of reciprocityRecommended by Michael D Greenfield and Joël Meunier

Of the various forms of cooperative and altruistic behavior, reciprocity remains the most contentious. Humans certainly exhibit reciprocity – under certain circumstances – and various non-human animals behave in ways suggesting that they do as well. Thus, evolutionary biologists have sought to explain why non-relatives might engage in altruistic transactions when a substantial delay occurs between helping and compensation; i.e. an individual may be a donor today and a beneficiary tomorrow, or vice-versa. This quest, aided by game theory and computer modeling late in the past century, identified some strategies for reciprocal behavior that could work – in theory. But when biologists looked for confirmation of these strategies in animals they found little evidence that stood up to rigorous testing. In a recent paper André and Nolfi [1] offer a compelling reason for this observed rarity of reciprocity: Reciprocal behavior that animals might exhibit is a bit more complex than any of the game theoretic strategies, and even the simplest forms of realistic behavior would entail several nearly simultaneous mutations, an unlikely occurrence. André and Nolfi [1] relied on neural networks to test actors, robots that could evolve helping and reciprocal behavior from a basal level of selfishness. In an extensive series of simulations, they found that reciprocal behavior did not take hold in a population, largely because the various intermediates to full reciprocity were eliminated before the subsequent mutations occurred. The findings are satisfying given our current knowledge of animal behavior, but questions remain. Notably, how does one account for those rare cases in which reciprocity does meet all the criteria? The authors suggest some possibilities, but an analysis will await their next study. Reference [1] André J-B, Nolfi S. 2016. Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. Scientific Reports 6:32785. doi: 10.1038/srep32785 | Evolutionary robotics simulations help explain why reciprocity is rare in nature. | André J-B, Nolfi S | <p>The relative rarity of reciprocity in nature, contrary to theoretical predictions that it should be widespread, is currently one of the major puzzles in social evolution theory. Here we use evolutionary robotics to solve this puzzle. We show th... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Michael D Greenfield | 2016-12-16 18:08:31 | View | |

16 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Spatiotemporal microbial evolution on antibiotic landscapesBaym M, Lieberman TD, Kelsic ED, Chait R, Gross R, Yelin I, Kishony R https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag0822A poster child for experimental evolutionRecommended by Daniel Rozen and Arjan de VisserEvolution is usually studied via two distinct approaches: by inferring evolutionary processes from relatedness patterns among living species or by observing evolution in action in the laboratory or field. A recent study by Baym and colleagues in Science [1] has now combined these approaches by taking advantage of the pattern left behind by spatially evolving bacterial populations. Evolution is often considered too slow to see, and can only be inferred by studying patterns of relatedness using phylogenetic trees. Increasingly, however, researchers are moving nature into the lab and watching as evolution unfolds under their noses. The field of experimental evolution follows evolutionary change in the laboratory over 10s to 1000s of generations, yielding insights into bacterial, viral, plant, or fly evolution (among many other species) that are simply not possible in the field. Yet, as powerful as experimental evolution is, it lacks a posterchild. There is no Galapagos finch radiation, nor a stunning series of cichlids to showcase to our students to pique their interests. Let’s face it, E. coli is no stickleback! And while practitioners of experimental evolution can explain the virtues of examining 60,000 generations of bacterial evolution in action, appreciating this nevertheless requires a level of insight and imagination that often eludes students, who need to see “it” to get it. Enter MEGA, an idea and a film that could become the new face of experimental evolution. It replaces big numbers of generations or images of scientists, with an actual picture of the scientific result. MEGA, or Microbial Evolution and Growth Arena, is essentially an enormous petri dish and is the brainchild of Michael Baym, Tami Leiberman and their colleagues in Roy Kishony’s lab at Technion Israel Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School. The idea of MEGA is to allow bacteria to swim over a spatially defined landscape while adapting to the local conditions, in this case antibiotics. When bacteria are inoculated onto one end of the plate they consume resources while swarming forward from the plate edge. In a few days, the bacteria grow into an area with antibiotics to which they are susceptible. This stops growth until a mutation arises that permits the bacteria to jump this hurdle, after which growth proceeds until the next hurdle of a 10-fold higher antibiotic concentration, and so on. By this simple approach, Baym et al. [1] evolved E. coli that were nearly 105-fold more resistant to two different antibiotics in just over 10 days. In addition, they identified the mutations that were required for these changes, showed that mutations conferring smaller benefits were required before bacteria could evolve maximal resistance, observed changes to the mutation rate, and demonstrated the importance of spatial structure in constraining adaptation. For one thing, the rate of resistance evolution is impressive, and also quite scary given the mounting threat of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. However, MEGA also offers a uniquely visual insight into evolutionary change. By taking successive images of the MEGA plate, the group was able to watch the bacteria move, get trapped because of their susceptibility to the antibiotic, and then get past these traps as new mutations emerged that increased resistance. Each transition showcases evolution in real time. In addition, by leaving a spatial pattern of evolutionary steps behind, the MEGA plate offers unique opportunities to thoroughly investigate these steps when the experiment is finished. For instance, subsequent steps in mutational pathways can be characterized, but also their effects on fitness can be quantified in situ by measuring changes in survival and reproduction. This new method is undoubtedly a boon to the field of experimental evolution and offers endless opportunities for experimental elaboration. Perhaps of equal importance, MEGA is a tool that is portable to the classroom and to the public at large. Don’t believe in evolution? Watch this. You only have time for a short internship or lab practical? No problem. Don’t worry much about antibiotic resistance? Check this out. Like the best experimental tools, MEGA is simple but allows for complicated insights. And even if it is less charismatic than a finch, it still allows for the kinds of “gee-whiz” insights that will get students hooked on evolutionary biology. Reference [1] Baym M, Lieberman TD, Kelsic ED, Chait R, Gross R, Yelin I, Kishony R. 2016. Spatiotemporal microbial evolution on antibiotic landscapes. Science 353:1147-1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0822 | Spatiotemporal microbial evolution on antibiotic landscapes | Baym M, Lieberman TD, Kelsic ED, Chait R, Gross R, Yelin I, Kishony R | <p>A key aspect of bacterial survival is the ability to evolve while migrating across spatially varying environmental challenges. Laboratory experiments, however, often study evolution in well-mixed systems. Here, we introduce an experimental devi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution | Daniel Rozen | 2016-12-14 14:26:06 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodesShapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12348Application of kin theory to long-standing problem in nematode production for biocontrolRecommended by Thomas Sappington and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerMuch research effort has been extended toward developing systems for managing soil inhabiting insect pests of crops with entomopathogenic nematodes as biocontrol agents. Although small plot or laboratory experiments may suggest a particular insect pest is vulnerable to management in this way, it is often difficult to scale-up nematode production for application at the field- and farm scale to make such a tactic viable. Part of the problem is that entomopathogenic nematode strains must be propagated by serial passage in vivo, because storage by freezing decreases fitness. At the same time, serial propagation results in loss of virulence (ability to infect) over generations in the laboratory, a phenomenon called attenuation. To probe the underlying reasons for development of attenuation, as a prerequisite to designing strategies to mitigate it, Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] turned to evolutionary theory of social conflict as a possible explanatory framework. Virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes depends on a combination of virulence factors, like various proteases, secreted by both the nematode and symbiotic bacteria to overcome host defenses. Attenuation is characterized in part by a reduced production of these factors. Invasion of a host involves simultaneous attack by a group of nematodes ("cooperators"), which together neutralize host defenses enough to allow individuals to successfully invade. "Cheaters" in the invading population can avoid the metabolic costs of producing virulence factors while reaping the benefits of infecting the host made vulnerable by the cooperators in the population. The authors hypothesize that an increase in frequency of cheaters may contribute to attenuation of virulence during serial propagation in the laboratory. The evolutionary dynamics of cheater frequency in a population have been explored in many contexts as part of kin selection theory. Cheaters can increase in a population by outcompeting cooperators in a host if overall relatedness within the invading population is low. Conversely, frequency of altruism, or costly cooperation, increases in a population if relatedness is high, which is enhanced by low effective dispersal. However, a population that is too isolated can suffer from inbreeding effects, and competition will occur mainly among relatives, which decreases the fitness benefits of altruism. Shapiro-Ilan and Raymond [1] tested changes in virulence and reproductive output in a serially propagated entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis floridensis. They compared lines of high or low relatedness, manipulated via multiplicity of infection (MOI) rates (where a low dose of nematodes gives high relatedness and a high dose gives low relatedness); and under global or local competition, manipulated by pooling populations emerging from all or only two host cadavers per generation, respectively. As predicted, treatments of high relatedness (low MOI) and global competition had the greatest level of reproduction, while all lines of low relatedness (high MOI) evolved decreased reproduction and decreased virulence, which led to extinction. The key finding was that lines in the high relatedness (low MOI) and low (local) competition treatment exhibited the most stable virulence through the 12 generations tested. Thus, to minimize attenuation of virulence while maintaining fitness of recently isolated entomopathogenic nematodes, the authors recommend insect hosts be inoculated with low doses of nematodes from inocula pools from as few cadavers as possible. The application of evolutionary theory, with a clever experimental design, to an important problem in pest management makes this paper particularly noteworthy. Reference [1] Shapiro-Ilan D, Raymond B. 2016. Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes. Evolutionary Applications 9:462-470. doi: 10.1111/eva.12348 | Limiting opportunities for cheating stabilizes virulence in insect parasitic nematodes | Shapiro-Ilan D. and B. Raymond | <p>Cooperative secretion of virulence factors by pathogens can lead to social conflict when cheating mutants exploit collective secretion, but do not contribute to it. If cheats outcompete cooperators within hosts, this can cause loss of virulence... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Thomas Sappington | 2016-12-15 18:33:39 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichensSpribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8287New partner at the core of macrolichen diversityRecommended by Enric Frago and Benoit FaconIt has long been known that most multicellular eukaryotes rely on microbial partners for a variety of functions including nutrition, immune reactions and defence against enemies. Lichens are probably the most popular example of a symbiosis involving a photosynthetic microorganism (an algae, a cyanobacteria or both) living embedded within the filaments of a fungus (usually an ascomycete). The latter is the backbone structure of the lichen, whereas the former provides photosynthetic products. Lichens are unique among symbioses because the structures the fungus and the photosynthetic microorganism form together do not resemble any of the two species living in isolation. Classic textbook examples like lichens are not often challenged and this is what Toby Spribille and his co-authors did with their paper published in July 2016 in Science [1]. This story started with the study of two species of macrolichens from the class of Lecanoromycetes that are commonly found in the mountains of Montana (US): Bryoria fremontii and B. tortuosa. For more than 90 years, these species have been known to differ in their chemical composition and colour, but studies performed so far failed in finding differences at the molecular level in both the mycobiont and the photobiont. These two species were therefore considered as nomenclatural synonyms, and the origin of their differences remained elusive. To solve this mystery, the authors of this work performed a transcriptome-wide analysis that, relative to previous studies, expanded the taxonomic range to all Fungi. This analysis revealed higher abundances of a previously unknown basidiomycete yeast from the genus Cyphobasidium in one of the lichen species, a pattern that was further confirmed by combining microscopy imaging and the fluorescent in situ hybridisation technique (FISH). Finding out that a previously unknown micro-organism changes the colour and the chemical composition of an organism is surprising but not new. For instance, bacterial symbionts are able to trigger colour changes in some insect species [2], and endophyte fungi are responsible for the production of defensive compounds in the leaves of several grasses [3]. The study by Spribille and his co-authors is fascinating because it demonstrates that Cyphobasidium yeasts have played a key role in the evolution and diversification of Lecanoromycetes, one of the most diverse classes of macrolichens. Indeed these basidiomycete yeasts were not only found in Bryoria but in 52 other lichen genera from all six continents, and these included 42 out of 56 genera in the family Parmeliaceae. Most of these sequences formed a highly supported monophyletic group, and a molecular clock revealed that the origin of many macrolichen groups occurred around the same time Cyphobasidium yeasts split from Cystobasidium, their nearest relatives. This newly discovered passenger is therefore an ancient inhabitant of lichens and has driven the evolution of this emblematic group of organisms. This study raises an important question on the stability of complex symbiotic partnerships. In intimate obligatory symbioses the evolutionary interests of both partners are often identical and what is good for one is also good for the other. This is the case of several insects that feed on poor diets like phloem and xylem sap, and which carry vertically-transmitted symbionts that provide essential nutrients. Molecular phylogenetic studies have repeatedly shown that in several insect groups transition to phloem or xylem feeding occurred at the same time these nutritional symbionts were acquired [4]. In lichens, an outstanding question is to know what was the key feature Cyphobasidium yeasts brought to the symbiosis. As suggested by the authors, these yeasts are likely to be involved in the production of secondary defensive metabolites and architectural structures, but, are these services enough to explain the diversity found in macrolichens? This paper is an appealing example of a multipartite symbiosis where the different partners share an ancient evolutionary history. References [1] Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353:488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8287 [2] Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, et al. 2010. Symbiotic Bacterium Modifies Aphid Body Color. Science 330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463 [3] Clay K. 1988. Fungal Endophytes of Grasses: A Defensive Mutualism between Plants and Fungi. Ecology 69:10–16. doi: 10.2307/1943155 [4] Moran NA. 2007. Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:8627–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611659104 | Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens | Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. | <p>For over 140 years, lichens have been regarded as a symbiosis between a single fungus, usually an ascomycete, and a photosynthesizing partner. Other fungi have long been known to occur as occasional parasites or endophytes, but the one lichen–o... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Enric Frago | 2016-12-15 05:46:14 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

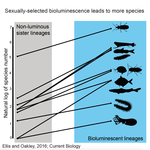

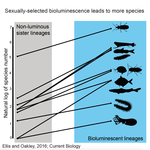

High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship DisplaysEllis EA, Oakley TH https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043Bioluminescent sexually selected traits as an engine for biodiversity across animal speciesRecommended by Astrid Groot and Carole SmadjaIn evolutionary biology, sexual selection is hypothesized to increase speciation rates in animals, as theory predicts that sexual selection will contribute to phenotypic diversification and affect rates of species accumulation at macro-evolutionary time scales. However, testing this hypothesis and gathering convincing evidence have proven difficult. Although some studies have shown a strong correlation between proxies of sexual selection and species diversity (mostly in birds), this relationship relies on some assumptions on the link between these proxies and the strength of sexual selection and is not detected in some other taxa, making taxonomically widespread conclusions impossible. In a recent study published in Current Biology [1], Ellis and Oakley provide strong evidence that bioluminescent sexual displays have driven high species richness in taxonomically diverse animal lineages, providing a crucial link between sexual selection and speciation. Ellis and Oakley [1] explored the scientific literature for well-resolved evolutionary trees with branches containing bioluminescent lineages and identified lineages that use light for courtship or camouflage in a wide range of marine and terrestrial taxa including insects, crustaceans, cephalopods, segmented worms, and fishes. The researchers counted the number of species in each bioluminescent clade and found that all groups with light-courtship displays had more species and faster rates of species accumulation than their non-luminous most closely related sister lineages or ancestors. In contrast, those groups that used bioluminescence for predator avoidance had a lower than expected rate of species richness on average. Nicely encompassing a diversity of taxa and neatly controlling for the rate of species accumulation of the encompassing clade, the results of Ellis and Oakley are clear-cut and provide the most comprehensive evidence to date for the hypothesis that sexual displays can act as drivers of speciation. One question this study incites is what is happening in terms of sexual selection in species displaying defensive bioluminescence or no bioluminescence at all: do those lineages use no mating signals at all or other mating signals that are less apparent, and will those experience lower levels of sexual selection than bioluminescent mating signals, i.e. consistent with Ellis and Oakley results? It would also be interesting to investigate the diversification rates in animal species using other modalities, such as chemical, acoustic or any other type of signals used by males, females or both sexes, to determine what types of sexual signals may be more generally drivers of speciation. References [1] Ellis EA, Oakley TH. 2016. High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays. Current Biology 26:1916–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.043 [2] Davis MP, Holcroft NI, Wiley EO, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2014. Species-specific bioluminescence facilitates speciation in the deep sea. Marine Biology 161:11391148. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2406-x [3] Davis MP, Sparks JS, Smith WL. 2016. Repeated and Widespread Evolution of Bioluminescence in Marine Fishes. PLoS One 11:e0155154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155154 [4] Claes JM, Nilsson D-E, Mallefet J, Straube N. 2015. The presence of lateral photophores correlates with increased speciation in deep-sea bioluminescent sharks. Royal Society Open Science 2:150219. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150219 | High Rates of Species Accumulation in Animals with Bioluminescent Courtship Displays | Ellis EA, Oakley TH | <p>One of the great mysteries of evolutionary biology is why closely related lineages accumulate species at different rates. Theory predicts that populations undergoing strong sexual selection will more quickly differentiate because of increased p... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Sexual Selection, Speciation | Astrid Groot | 2016-12-14 19:01:59 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | <p>Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in polli... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance lociMetzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12854Evidence of epistasis provides further support to the Red Queen theory of host-parasite coevolutionRecommended by Adele Mennerat and Thierry LefèvreAccording to the Red Queen theory of antagonistic host-parasite coevolution, adaptation of parasites to the most common host genotype results in negative frequency-dependent selection whereby rare host genotypes are favoured. Assuming that host resistance relies on a genetic host-parasite (mis)match involving several linked loci, then recombination appears as much more efficient than parthenogenesis in generating new resistant host genotypes. This has long been proposed to explain one of the biggest so-called paradoxes in evolutionary biology, i.e. the maintenance of recombination despite its twofold cost. Evidence from various study systems indicates that successful infection (and hence host resistance) depends on a genetic match between the parasite’s and the host’s genotype via molecular interactions involving elicitor/receptor mechanisms. However the key assumption of epistasis, i.e. that this genetic host-parasite match involves several linked resistance loci, remained unsupported so far. Metzger and coauthors [1] now provide empirical support for it. Daphnia magna can reproduce both sexually and clonally and their well-studied interaction with Pasteuria ramosa makes them an excellent model system to investigate the genetics of host resistance. D. magna hosts were found to be either resistant (complete lack of attachment of parasite spores to the host’s foregut) or susceptible (full attachment). In this study the authors carried out an elegant Mendelian genetic investigation by performing multiple crosses between four host genotypes differing in their resistance to two different parasite isolates [1]. Their results show that resistance of D. magna to each of the two P. ramosa isolates relies on Mendelian inheritance at two loci that are linked (A and B), each of them having two alleles with dominant resistance; furthermore resistance to one parasite isolate confers susceptibility to the other. They also show that a third locus appears to confer double resistance (C), but that even double resistant hosts remain susceptible to other parasite isolates, and hence that universal host resistance is lacking – all of this supporting the Red Queen theory. This paper demonstrates with a high level of clarity that host resistance is governed by multiple linked loci. The assumption of epistasis between resistance loci is supported, which makes it possible for sexual recombination to be maintained by antagonistic host-parasite coevolution. Reference [1] Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. 2016. The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci. Evolution 70:480-487. doi: 10.1111/evo.12854 | The Red Queen lives: epistasis between linked resistance loci | Metzger CMJA, Luijckx P, Bento G, Mariadassou M, Ebert D. | <p>A popular theory explaining the maintenance of genetic recombination (sex) is the Red Queen Theory. This theory revolves around the idea that time-lagged negative frequency-dependent selection by parasites favors rare host genotypes generated t... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Adele Mennerat | 2016-12-14 13:58:53 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversionsDagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12954The spread of chromosomal inversions as a mechanism for reinforcementRecommended by Denis Roze and Thomas Broquet

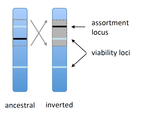

Several examples of chromosomal inversions carrying genes affecting mate choice have been reported from various organisms. Furthermore, inversions are also frequently involved in genetic isolation between populations or species. Past work has shown that inversions can spread when they capture not only some loci involved in mate choice but also loci involved in incompatibilities between hybridizing populations [1]. In this new paper [2], the authors derive analytical approximations for the selection coefficient associated with an inversion suppressing recombination between a locus involved in mate choice and one (or several) locus involved in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Two mechanisms for mate choice are considered: assortative mating based on the allele present at a single locus, or a trait-preference model where one locus codes for the trait and another for the preference. The results show that such an inversion is generally favoured, the selective advantage associated with the inversion being strongest when hybridization is sufficiently frequent. Assuming pairwise epistatic interactions between loci involved in incompatibilities, selection for the inversion increases approximately linearly with the number of such loci captured by the inversion. This paper is a good read for several reasons. First, it presents the problem clearly (e.g. the introduction provides a clear and concise presentation of the issue and past work) and its crystal-clear writing facilitates the reader's understanding of theoretical approaches and results. Second, the analysis is competently done and adds to previous work by showing that very general conditions are expected to be favourable to the spread of the type of inversion considered here. And third, it provides food for thought about the role of inversions in the origin or the reinforcement of divergence between nascent species. One result of this work is that an inversion linked to pre-zygotic isolation "is favoured so long as there is viability selection against recombinant genotypes", suggesting that genetic incompatibilities must have evolved first and that inversions capturing mating preference loci may then enhance pre-existing reproductive isolation. However, the results also show that inversions are more likely to be favoured in hybridizing populations among which gene flow is still high, rather than in more strongly isolated populations. This matches the observation that inversions are more frequently observed between sympatric species than between allopatric ones. References [1] Trickett AJ, Butlin RK. 1994. Recombination Suppressors and the Evolution of New Species. Heredity 73:339-345. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1994.180 [2] Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M. 2016. Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions. Evolution 70: 1465–1472. doi: 10.1111/evo.12954 | Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions | Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M | <p>Chromosomal inversions are frequently implicated in isolating species. Models have shown how inversions can evolve in the context of postmating isolation. Inversions are also frequently associated with mating preferences, a topic that has not b... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Denis Roze | 2016-12-13 22:11:54 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang