Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * ▲ | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Nov 2020

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosisDavid Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewersMonnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time. References [1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265 | Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View | |

03 May 2020

When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue?Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl https://doi.org/10.1101/622142Reconciling the upsides and downsides of migration for evolutionary rescueRecommended by Claudia Bank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The evolutionary response of populations to changing or novel environments is a topic that unites the interests of evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and biomedical researchers [1]. A prominent phenomenon in this research area is evolutionary rescue, whereby a population that is otherwise doomed to extinction survives due to the spread of new or pre-existing mutations that are beneficial in the new environment. Scenarios of evolutionary rescue require a specific set of parameters: the absolute growth rate has to be negative before the rescue mechanism spreads, upon which the growth rate becomes positive. However, potential examples of its relevance exist (e.g., [2]). From a theoretical point of view, the technical challenge but also the beauty of evolutionary rescue models is that they combine the study of population dynamics (i.e., changes in the size of populations) and population genetics (i.e., changes in the frequencies in the population). Together, the potential relevance of evolutionary rescue in nature and the models' theoretical appeal has resulted in a suite of modeling studies on the subject in recent years. References [1] Bell, G. (2017). Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48(1), 605-627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue? | Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl | <p>Experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the impact of gene flow on the probability of evolutionary rescue in structured habitats. Mathematical modelling and simulations of evolutionary rescue in spatially or otherwise structured p... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Claudia Bank | 2019-05-22 11:12:13 | View | |

23 Apr 2020

How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridisJulien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Estoup, Benoit Facon https://doi.org/10.1101/849968Selection on a single trait does not recapitulate the evolution of life-history traits seen during an invasionRecommended by Inês Fragata and Ben Phillips based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersBiological invasions are natural experiments, and often show that evolution can affect dynamics in important ways [1-3]. While we often think of invasions as a conservation problem stemming from anthropogenic introductions [4,5], biological invasions are much more commonplace than this, including phenomena as diverse as natural range shifts, the spread of novel pathogens, and the growth of tumors. A major question across all these settings is which set of traits determine the ability of a population to invade new space [6,7]. Traits such as: increased growth or reproductive rate, dispersal ability and ability to defend from predation often show large evolutionary shifts across invasion history [1,6,8]. Are such multi-trait shifts driven by selection on multiple traits, or a correlated response by multiple traits to selection on one? Resolving this question is important for both theoretical and practical reasons [9,10]. But despite the importance of this issue, it is not easy to perform the necessary manipulative experiments [9]. References [1] Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S. et al. (2001). The population biology of invasive species. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 32(1), 305-332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 | How do invasion syndromes evolve? An experimental evolution approach using the ladybird Harmonia axyridis | Julien Foucaud, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Virginie Ravigné, Laure Olazcuaga, Anne Loiseau, Aurelien Ausset, Su Wang, Lian-Sheng Zang, Nicolas Lemenager, Ashraf Tayeh, Arthur Weyna, Pauline Gneux, Elise Bonnet, Vincent Dreuilhe, Bastien Poutout, Arnaud Est... | <p>Experiments comparing native to introduced populations or distinct introduced populations to each other show that phenotypic evolution is common and often involves a suit of interacting phenotypic traits. We define such sets of traits that evol... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Inês Fragata | 2019-11-29 07:07:00 | View | |

03 Oct 2018

Range size dynamics can explain why evolutionarily age and diversification rate correlate with contemporary extinction risk in plantsAndrew J. Tanentzap, Javier Igea, Matthew G. Johnston, Matthew J. Larcombe https://doi.org/10.1101/152215Are both very young and the very old plant lineages at heightened risk of extinction?Recommended by Arne Mooers based on reviews by Dan Greenberg and 1 anonymous reviewerHuman economic activity is responsible for the vast majority of ongoing extinction, but that does not mean lineages are being affected willy-nilly. For amphibians [1] and South African flowering plants [2], young species have a somewhat higher than expected chance of being threatened with extinction. In contrast, older Australian marsupial lineages seem to be more at risk [3]. Both of the former studies suggested that situations leading to peripheral isolation might simultaneously increase ongoing speciation and current threat via small geographic range, while the authors of the latter study suggested that older species might have evolved increasingly narrow niches. Here, Andrew Tanentzap and colleagues [4] dig deeper into the putative links between species age, niche breadth and threat status. Across 500-some plant genera worldwide, they find that, indeed, ""younger"" species (i.e. from younger and faster-diversifying genera) were more likely to be listed as imperiled by the IUCN, consistent with patterns for amphibians and African plants. Given this, results from their finer-level analyses of conifers are initially bemusing: here, ""older"" (i.e., on longer terminal branches) species were at higher risk. This would make conifers more like Australian marsupials, with the rest of the plants being more like amphibians. However, here where the data were more finely grained, the authors detected a second interesting pattern: using an intriguing matched-pair design, they detect a signal of conifer species niches seemingly shrinking as a function of age. The authors interpret this as consistent with increasing specialization, or loss of ancestral warm wet habitat, over paleontological time. It is true that conifers in general are older than plants more generally, with some species on branches that extend back many 10s of millions of years, and so a general loss of suitable habitat makes some sense. If so, both the pattern for all plants (small initial ranges heightening extinction) and the pattern for conifers (eventual increasing specialization or habitat contraction heightening extinction) could occur, each on a different time scale. As a coda, the authors detected no effect of age on threat status in palms; however, this may be both because palms have already lost species to climate-change induced extinction, and because they are thought to speciate more via long-distance dispersal and adaptive divergence then via peripheral isolation. References [1] Greenberg, D. A., & Mooers, A. Ø. (2017). Linking speciation to extinction: Diversification raises contemporary extinction risk in amphibians. Evolution Letters, 1, 40–48. doi: 10.1002/evl3.4 | Range size dynamics can explain why evolutionarily age and diversification rate correlate with contemporary extinction risk in plants | Andrew J. Tanentzap, Javier Igea, Matthew G. Johnston, Matthew J. Larcombe | <p>Extinction threatens many species, yet few factors predict this risk across the plant Tree of Life (ToL). Taxon age is one factor that may associate with extinction if occupancy of geographic and adaptive zones varies with time, but evidence fo... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Arne Mooers | 2018-02-01 21:01:19 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host speciesFanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417What makes a parasite successful? Parasitoid wasp venoms evolve rapidly in a host-specific mannerRecommended by Élio Sucena based on reviews by Simon Fellous, alexandre leitão and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitoid wasps have developed different mechanisms to increase their parasitic success, usually at the expense of host survival (Fellowes and Godfray, 2000). Eggs of these insects are deposited inside the juvenile stages of their hosts, which in turn deploy several immune response strategies to eliminate or disable them (Yang et al., 2020). Drosophila melanogaster protects itself against parasitoid attacks through the production of specific elongated haemocytes called lamellocytes which form a capsule around the invading parasite (Lavine and Strand, 2002; Rizki and Rizki, 1992) and the subsequent activation of the phenol-oxidase cascade leading to the release of toxic radicals (Nappi et al., 1995). On the parasitoid side, robust responses have evolved to evade host immune defenses as for example the Drosophila-specific endoparasite Leptopilina boulardi, which releases venom during oviposition that modifies host behaviour (Varaldi et al., 2006) and inhibits encapsulation (Gueguen et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012).

References Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Gatti, J.-L., Colinet, D. and Poirié, M. (2021) Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species. bioRxiv, 2020.10.24.353417, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417 Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Kremmer, L., Rebuf, C., Gatti, J.-L., Malausa, T., Colinet, D., Poiré, M. and Léne. (2019). Rapid and Differential Evolution of the Venom Composition of a Parasitoid Wasp Depending on the Host Strain. Toxins, 11(629). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11110629 Colinet, D., Deleury, E., Anselme, C., Cazes, D., Poulain, J., Azema-Dossat, C., Belghazi, M., Gatti, J. L. and Poirié, M. (2013). Extensive inter- and intraspecific venom variation in closely related parasites targeting the same host: The case of Leptopilina parasitoids of Drosophila. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43(7), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.010 Colinet, D., Dubuffet, A., Cazes, D., Moreau, S., Drezen, J. M. and Poirié, M. (2009). A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 33(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013 Fellowes, M. D. E. and Godfray, H. C. J. (2000). The evolutionary ecology of resistance to parasitoids by Drosophila. Heredity, 84(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00685.x Gueguen, G., Rajwani, R., Paddibhatla, I., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2011). VLPs of Leptopilina boulardi share biogenesis and overall stellate morphology with VLPs of the heterotoma clade. Virus Research, 160(1–2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.005 Lavine, M. D. and Strand, M. R. (2002). Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32(10), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9 Martinez, J., Duplouy, A., Woolfit, M., Vavre, F., O’Neill, S. L. and Varaldi, J. (2012). Influence of the virus LbFV and of Wolbachia in a host-parasitoid interaction. PloS One, 7(4), e35081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035081 Nappi, A. J., Vass, E., Frey, F. and Carton, Y. (1995). Superoxide anion generation in Drosophila during melanotic encapsulation of parasites. European Journal of Cell Biology, 68(4), 450–456. Poirié, M., Colinet, D. and Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004 Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 16(2–3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z Schlenke, T. A., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathogens, 3(10), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030158 Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology, 132(Pt 6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009930 Yang, L., Qiu, L., Fang, Q., Stanley, D. W. and Gong‐Yin, Y. (2020). Cellular and humoral immune interactions between Drosophila and its parasitoids. Insect Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12863

| Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species | Fanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié | <p>Female endoparasitoid wasps usually inject venom into hosts to suppress their immune response and ensure offspring development. However, the parasitoid’s ability to evolve towards increased success on a given host simultaneously with the evolut... |  | Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Élio Sucena | 2020-10-26 15:00:55 | View | |

03 Aug 2017

POSTPRINT

Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradientsNoémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13111What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger: can Fisher’s Geometric model predict antibiotic resistance evolution?Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank

The increasing number of reported cases of antibiotic resistance is one of today’s major public health concerns. Dealing with this threat involves understanding what drives the evolution of antibiotic resistance and investigating whether we can predict (and subsequently avoid or circumvent) it [1]. References [1] Palmer AC, and Kishony R. 2013. Understanding, predicting and manipulating the genotypic evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nature Review Genetics 14: 243—248. doi: 10.1038/nrg3351 [2] Tenaillon O. 2014. The utility of Fisher’s geometric model in evolutionary genetics. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 45: 179—201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091846 [3] Blanquart F and Bataillon T. 2016. Epistasis and the structure of fitness landscapes: are experimental fitness landscapes compatible with Fisher’s geometric model? Genetics 203: 847—862. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.182691 [4] Harmand N, Gallet R, Jabbour-Zahab R, Martin G and Lenormand T. 2017. Fisher’s geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients. Evolution 71: 23—37. doi: 10.1111/evo.13111 [5] de Visser, JAGM, and Krug J. 2014. Empirical fitness landscapes and the predictability of evolution. Nature 15: 480—490. doi: 10.1038/nrg3744 [6] Palmer AC, Toprak E, Baym M, Kim S, Veres A, Bershtein S and Kishony R. 2015. Delayed commitment to evolutionary fate in antibiotic resistance fitness landscapes. Nature Communications 6: 1—8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8385 | Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients | Noémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Fisher's geometrical model (FGM) has been widely used to depict the fitness effects of mutations. It is a general model with few underlying assumptions that gives a large and comprehensive view of adaptive processes. It is thus attractive in se... |  | Adaptation | Inês Fragata | 2017-08-01 16:06:02 | View | |

25 Jun 2024

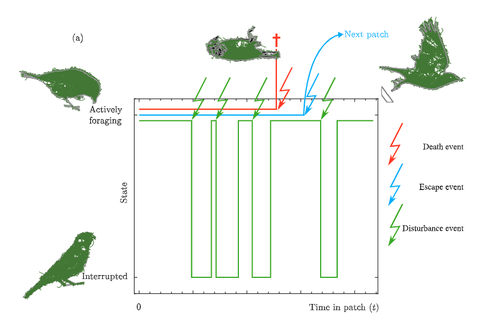

Taking fear back into the Marginal Value Theorem: the risk-MVT and optimal boldnessVincent Calcagno, Frederic Grognard, Frederic M Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.31.564970Applying the marginal value theorem when risk affects foraging behaviorRecommended by Stephen Proulx based on reviews by Taom Sakal and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Taom Sakal and 1 anonymous reviewer

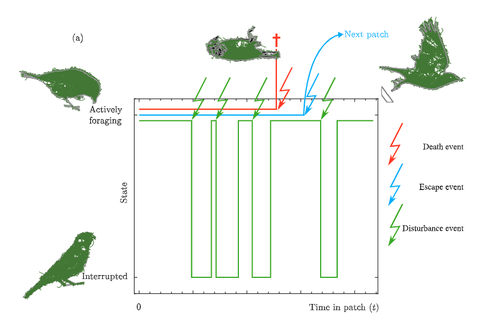

Foraging has been long been studied from an economic perspective, where the costs and benefits of foraging decisions are measured in terms of a single currency of energy which is then taken as a proxy for fitness. A mainstay foraging theory is Charnov’s Marginal Value Theorem (Charnov, 1976), or MVT, which includes a graphical interpretation and has been applied to an enormous range topics in behavioral ecology (Menezes , 2022). Empirical studies often find that animals deviate from MVT, sometimes in that they predictably stay longer than the optimal time. One explanation for this comes from state based models of behavior (Nonacs 2001) Now Calcgano and colleagues (2024) set out to extend and unify foraging models that include various aspects of risk to the foragers, and propose using a risk MVT, or rMVT. They consider three types of risk that foragers face, disturbance, escape, and death. Disturbance represents scenarios where the forager is either physically interrupted in their foraging, or stops foraging temporarily because of the presence of a predator (i.e. a fear response). Such a disturbance can be thought of as altering the gain function for resources acquired while foraging in the patch, allowing the rMVT to be applied in a familiar way with only a reinterpretation of the gain function. In the escape scenarios, foragers are forced to leave a patch because of predator behavior, and therefore artificially decrease their foraging time as compared with their desired foraging time. Now, optimization can be calculated based on this expected time foraging, which means that in effect the forager compensates for the reduced time in the patch by modifying their view of how long they will actually forage. Finally they consider scenarios where risk may result in death, and further divide this into two cases, one where foraging returns are instantaneously converted to fitness, and another where they are only converted in between foraging bouts. This represents an important case to consider, because the total number of foraging trips now depends on the rate of predator attack. In these scenarios, the boldness of the forager is decreased and they become more risk-averse. The authors find that under the disturbance and escape scenarios, patch residence time can actually go up with risk. This is in effect because they are depleting the patch less per unit time, because a larger fraction of time is taken up with avoiding predators. In terms of field applications, this may differ from what is typically considered as risk, since harassment by conspecifics has the same disturbance effect as predator avoidance behaviors. Most experiments on foraging are done in the absence of risk or signals of risk, i.e. in laboratory or otherwise controlled environments. The rMVT predictions deviate from non-risk scenarios in complex ways, in that the patch residence time may increase or decrease under risk. It is also important to note that foragers have evolved their foraging strategies in response to the risk profiles that they have historically experienced, and therefore experiments lacking risk may still show that foragers alter their behavior from the MVT predictions in a way that reflects historical levels of risk. References Calcagno, V., Grognard, F., Hamelin, F.M. and Mailleret, L. (2024). Taking fear back into the Marginal Value Theorem: the risk-MVT and optimal boldness. bioRxiv, 2023.10.31.564970, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.31.564970 Charnov E. (1976). Optimal foraging the marginal value theorem. Theor Popul Biol. 9, 129–136. Menezes, JFS (2022).The marginal value theorem as a special case of the ideal free distribution. Ecological Modelling 468:109933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2022.109933 Nonacs, P. 2001. State dependent behavior and the Marginal Value Theorem. Behavioral Ecology 12(1) 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.beheco.a000381 | Taking fear back into the Marginal Value Theorem: the risk-MVT and optimal boldness | Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Grognard, Frederic M Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret | <p>Foragers exploiting heterogeneous habitats must make strategic movement decisions in order to maximize fitness. Foraging theory has produced very general formalizations of the optimal patch-leaving decisions rational individuals should make. On... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Stephen Proulx | 2023-11-03 13:25:16 | View | |

19 Mar 2018

Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environmentLeonardo Bacigalupe, Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Aura M Barria, Avia Gonzalez-Mendez, Manuel Ruiz-Aravena, Mark Trinder, Barry Sinervo https://doi.org/10.1101/191825Is thermal plasticity itself shaped by natural selection? An assessment with desert frogsRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Dries Bonte, Wolf Blanckenhorn and Nadia Aubin-HorthIt is well known that climatic factors – most notably temperature, season length, insolation and humidity – shape the thermal niche of organisms on earth through the action of natural selection. But how is this achieved precisely? Much of thermal tolerance is actually mediated by phenotypic plasticity (as opposed to genetic adaptation). A prominent expectation is that environments with greater (daily and/or annual) thermal variability select for greater plasticity, i.e. better acclimation capacity. Thus, plasticity might be selected per se. A Chilean group around Leonardo Bacigalupe assessed natural selection in the wild in one marginal (and extreme) population of the four-eyed frog Pleurodema thaul (Anura: Leptodactylidae) in an isolated oasis in the Atacama Desert, permitting estimation of mortality without much potential of confounding it with migration [1]. Several thermal traits were considered: CTmax – the critical maximal temperature; CTmin – the critical minimum temperature; Tpref – preferred temperature; Q10 – thermal sensitivity of metabolism; and body mass. Animals were captured in the wild and subsequently assessed for thermal traits in the laboratory at two acclimation temperatures (10° & 20°C), defining the plasticity in all traits as the difference between the traits at the two acclimation temperatures. Thereafter the animals were released again in their natural habitat and their survival was monitored over the subsequent 1.5 years, covering two breeding seasons, to estimate viability selection in the wild. The authors found and conclude that, aside from larger body size increasing survival (an unsurprising result), plasticity does not seem to be systematically selected directly, while some of the individual traits show weak signs of selection. Despite limited sample size (ca. 80 frogs) investigated in only one marginal but very seasonal population, this study is interesting because selection on plasticity in physiological thermal traits, as opposed to selection on the thermal traits themselves, is rarely investigated. The study thus also addressed the old but important question of whether plasticity (i.e. CTmax-CTmin) is a trait by itself or an epiphenomenon defined by the actual traits (CTmax and CTmin) [2-5]. Given negative results, the main question could not be ultimately solved here, so more similar studies should be performed. References [1] Bacigalupe LD, Gaitan-Espitia, JD, Barria AM, Gonzalez-Mendez A, Ruiz-Aravena M, Trinder M & Sinervo B. 2018. Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environment. bioRxiv 191825, ver. 5 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/191825 | Natural selection on plasticity of thermal traits in a highly seasonal environment | Leonardo Bacigalupe, Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Aura M Barria, Avia Gonzalez-Mendez, Manuel Ruiz-Aravena, Mark Trinder, Barry Sinervo | <p>For ectothermic species with broad geographical distributions, latitudinal/altitudinal variation in environmental temperatures (averages and extremes) are expected to shape the evolution of physiological tolerances and the acclimation capacity ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2017-09-22 23:17:40 | View | |

15 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichensSpribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8287New partner at the core of macrolichen diversityRecommended by Enric Frago and Benoit FaconIt has long been known that most multicellular eukaryotes rely on microbial partners for a variety of functions including nutrition, immune reactions and defence against enemies. Lichens are probably the most popular example of a symbiosis involving a photosynthetic microorganism (an algae, a cyanobacteria or both) living embedded within the filaments of a fungus (usually an ascomycete). The latter is the backbone structure of the lichen, whereas the former provides photosynthetic products. Lichens are unique among symbioses because the structures the fungus and the photosynthetic microorganism form together do not resemble any of the two species living in isolation. Classic textbook examples like lichens are not often challenged and this is what Toby Spribille and his co-authors did with their paper published in July 2016 in Science [1]. This story started with the study of two species of macrolichens from the class of Lecanoromycetes that are commonly found in the mountains of Montana (US): Bryoria fremontii and B. tortuosa. For more than 90 years, these species have been known to differ in their chemical composition and colour, but studies performed so far failed in finding differences at the molecular level in both the mycobiont and the photobiont. These two species were therefore considered as nomenclatural synonyms, and the origin of their differences remained elusive. To solve this mystery, the authors of this work performed a transcriptome-wide analysis that, relative to previous studies, expanded the taxonomic range to all Fungi. This analysis revealed higher abundances of a previously unknown basidiomycete yeast from the genus Cyphobasidium in one of the lichen species, a pattern that was further confirmed by combining microscopy imaging and the fluorescent in situ hybridisation technique (FISH). Finding out that a previously unknown micro-organism changes the colour and the chemical composition of an organism is surprising but not new. For instance, bacterial symbionts are able to trigger colour changes in some insect species [2], and endophyte fungi are responsible for the production of defensive compounds in the leaves of several grasses [3]. The study by Spribille and his co-authors is fascinating because it demonstrates that Cyphobasidium yeasts have played a key role in the evolution and diversification of Lecanoromycetes, one of the most diverse classes of macrolichens. Indeed these basidiomycete yeasts were not only found in Bryoria but in 52 other lichen genera from all six continents, and these included 42 out of 56 genera in the family Parmeliaceae. Most of these sequences formed a highly supported monophyletic group, and a molecular clock revealed that the origin of many macrolichen groups occurred around the same time Cyphobasidium yeasts split from Cystobasidium, their nearest relatives. This newly discovered passenger is therefore an ancient inhabitant of lichens and has driven the evolution of this emblematic group of organisms. This study raises an important question on the stability of complex symbiotic partnerships. In intimate obligatory symbioses the evolutionary interests of both partners are often identical and what is good for one is also good for the other. This is the case of several insects that feed on poor diets like phloem and xylem sap, and which carry vertically-transmitted symbionts that provide essential nutrients. Molecular phylogenetic studies have repeatedly shown that in several insect groups transition to phloem or xylem feeding occurred at the same time these nutritional symbionts were acquired [4]. In lichens, an outstanding question is to know what was the key feature Cyphobasidium yeasts brought to the symbiosis. As suggested by the authors, these yeasts are likely to be involved in the production of secondary defensive metabolites and architectural structures, but, are these services enough to explain the diversity found in macrolichens? This paper is an appealing example of a multipartite symbiosis where the different partners share an ancient evolutionary history. References [1] Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353:488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8287 [2] Tsuchida T, Koga R, Horikawa M, et al. 2010. Symbiotic Bacterium Modifies Aphid Body Color. Science 330:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1195463 [3] Clay K. 1988. Fungal Endophytes of Grasses: A Defensive Mutualism between Plants and Fungi. Ecology 69:10–16. doi: 10.2307/1943155 [4] Moran NA. 2007. Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:8627–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611659104 | Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens | Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. | <p>For over 140 years, lichens have been regarded as a symbiosis between a single fungus, usually an ascomycete, and a photosynthesizing partner. Other fungi have long been known to occur as occasional parasites or endophytes, but the one lichen–o... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Enric Frago | 2016-12-15 05:46:14 | View | |

18 Aug 2020

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in FranceGonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in FranceRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewersSequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures. References [1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2 | Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer