Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Apr 2020

Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen https://doi.org/10.1101/662577Genomic structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaiceRecommended by Maren Wellenreuther based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersAwareness has been growing that structural variants in the genome of species play a fundamental role in adaptive evolution and diversification [1]. Here, Le Moan and co-authors [2] report empirical genomic-wide SNP data on the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) across a major environmental transmission zone, ranging from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea. Regions of high linkage disequilibrium suggest the presence of two structural variants that appear to have evolved 220 kya. These two putative structural variants show weak signatures of isolation by distance when contrasted against the rest of the genome, but the frequency of the different putative structural variants appears to co-vary in some parts of the studied range with the environment, indicating the involvement of both selective and neutral processes. This study adds to the mounting body of evidence that structural genomic variants harbour significant information that allows species to respond and adapt to the local environmental context. References [1] Wellenreuther, M., Mérot, C., Berdan, E., & Bernatchez, L. (2019). Going beyond SNPs: the role of structural genomic variants in adaptive evolution and species diversification. Molecular ecology, 28(6), 1203-1209. doi: 10.1111/mec.15066 | Evolution at two time-frames: ancient and common origin of two structural variants involved in local adaptation of the European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) | Alan Le Moan, Dorte Bekkevold & Jakob Hemmer-Hansen | <p>Changing environmental conditions can lead to population diversification through differential selection on standing genetic variation. Structural variant (SV) polymorphisms provide examples of ancient alleles that in time become associated with... | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Maren Wellenreuther | 2019-07-13 12:44:01 | View | ||

06 Apr 2021

How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans?Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030Be careful when studying selection based on polygenic score overdispersionRecommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been a great promise for our understanding of the connection between genotype and phenotype. Today, the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog contains 251,401 associations from 4,961 studies (1). This wealth of studies has also generated interest to use the summary statistics beyond the few top hits in order to make predictions for individuals without known phenotype, e.g. to predict polygenic risk scores or to study polygenic selection by comparing different groups. For instance, polygenic selection acting on the most studied polygenic trait, height, has been subject to multiple studies during the past decade (e.g. 2–6). They detected north-south gradients in Europe which were consistent with expectations. However, their GWAS summary statistics were based on the GIANT consortium data set, a meta-analysis of GWAS conducted in different European cohorts (7,8). The availability of large data sets with less stratification such as the UK Biobank (9) has led to a re-evaluation of those results. The nature of the GIANT consortium data set was realized to represent a potential problem for studies of polygenic adaptation which led several of the authors of the original articles to caution against the interpretations of polygenic selection on height (10,11). This was a great example on how the scientific community assessed their own earlier results in a critical way as more data became available. At the same time it left the question whether there is detectable polygenic selection separating populations more open than ever. Generally, recent years have seen several articles critically assessing the portability of GWAS results and risk score predictions to other populations (12–14). Refoyo-Martínez et al. (15) are now presenting a systematic assessment on the robustness of cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans. They compiled GWAS results for complex traits which have been studied in more than one cohort and then use allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes Project data (16) set to detect signals of polygenic score overdispersion. As the source for the allele frequencies is kept the same across all tests, differences between the signals must be caused by the underlying GWAS. The results are concerning as the level of overdispersion largely depends on the choice of GWAS cohort. Cohorts with homogenous ancestries show little to no overdispersion compared to cohorts of mixed ancestries such as meta-analyses. It appears that the meta-analyses fail to fully account for stratification in their data sets. The authors based most of their analyses on the heavily studied trait height. Additionally, they use educational attainment (measured as the number of school years of an individual) as an example. This choice was due to the potential over- or misinterpretation of results by the media, the general public and by far right hate groups. Such traits are potentially confounded by unaccounted cultural and socio-economic factors. Showing that previous results about polygenic selection on educational attainment are not robust is an important result that needs to be communicated well. This forms a great example for everyone working in human genomics. We need to be aware that our results can sometimes be misinterpreted. And we need to make an effort to write our papers and communicate our results in a way that is honest about the limitations of our research and that prevents the misuse of our results by hate groups. This article represents an important contribution to the field. It is cruicial to be aware of potential methodological biases and technical artifacts. Future studies of polygenic adaptation need to be cautious with their interpretations of polygenic score overdispersion. A recommendation would be to use GWAS results obtained in homogenous cohorts. But even if different biobank-scale cohorts of homogeneous ancestry are employed, there will always be some remaining risk of unaccounted stratification. These conclusions may seem sobering but they are part of the scientific process. We need additional controls and new, different methods than polygenic score overdispersion for assessing polygenic selection. Last year also saw the presentation of a novel approach using sequence data and GWAS summary statistics to detect directional selection on a polygenic trait (17). This new method appears to be robust to bias stemming from stratification in the GWAS cohort as well as other confounding factors. Such new developments show light at the end of the tunnel for the use of GWAS summary statistics in the study of polygenic adaptation. References 1. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1005–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1120 2. Turchin MC, Chiang CW, Palmer CD, Sankararaman S, Reich D, Hirschhorn JN. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs. Nature Genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):1015–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2368 3. Berg JJ, Coop G. A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2014 Aug 7;10(8):e1004412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004412 4. Robinson MR, Hemani G, Medina-Gomez C, Mezzavilla M, Esko T, Shakhbazov K, et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nature Genetics. 2015 Nov;47(11):1357–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3401 5. Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015 Dec;528(7583):499–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152 6. Racimo F, Berg JJ, Pickrell JK. Detecting polygenic adaptation in admixture graphs. Genetics. 2018. Arp;208(4):1565–1584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300489 7. Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7317):832–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09410 8. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014 Nov;46(11):1173–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097 9. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z 10. Berg JJ, Harpak A, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Joergensen AM, Mostafavi H, Field Y, et al. Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39725. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39725 11. Sohail M, Maier RM, Ganna A, Bloemendal A, Martin AR, Turchin MC, et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39702. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39702 12. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics. 2019 Apr;51(4):584–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x 13. Bitarello BD, Mathieson I. Polygenic Scores for Height in Admixed Populations. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):4027–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401658 14. Uricchio LH, Kitano HC, Gusev A, Zaitlen NA. An evolutionary compass for detecting signals of polygenic selection and mutational bias. Evolution Letters. 2019;3(1):69–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.97 15. Refoyo-Martínez A, Liu S, Jørgensen AM, Jin X, Albrechtsen A, Martin AR, Racimo F. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? bioRxiv, 2021, 2020.07.13.200030, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030 16. Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Sep 30;526(7571):68–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 17. Stern AJ, Speidel L, Zaitlen NA, Nielsen R. Disentangling selection on genetically correlated polygenic traits using whole-genome genealogies. bioRxiv. 2020 May 8;2020.05.07.083402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.083402 | How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? | Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo | <p>Over the past decade, summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been used to detect and quantify polygenic adaptation in humans. Several studies have reported signatures of natural selection at sets of SNPs associated... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genetic conflicts, Human Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | 2020-08-14 15:06:54 | View | |

11 May 2023

Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineagesAlejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559Flexibility in Aphid Endosymbiosis: Dual Symbioses Have Evolved Anew at Least Six TimesRecommended by Olivier Tenaillon based on reviews by Alex C. C. Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this intriguing study (Manzano-Marín et al. 2022) by Alejandro Manzano-Marin and his colleagues, the association between aphids and their symbionts is investigated through meta-genomic analysis of new samples. These associations have been previously described as leading to fascinating genomic evolution in the symbiont (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). The bacterial genomes exhibit a significant reduction in size and the range of functions performed. They typically lose the ability to produce many metabolites or biobricks created by the host, and instead, streamline their metabolism by focusing on the amino acids that the host cannot produce. This level of co-evolution suggests a stable association between the two partners. However, the new data suggests a much more complex pattern as multiple independent acquisitions of co-symbionts are observed. Co-symbiont acquisition leads to a partition of the functions carried out on the bacterial side, with the new co-symbiont taking over some of the functions previously performed by Buchnera. In most cases, the new co-symbiont also brings the ability to produce B1 vitamin. Various facultative symbiotic taxa are recruited to be co-symbionts, with the frequency of acquisition related to the bacterial niche and lifestyle. REFERENCES Manzano-Marín, Alejandro, Armelle Coeur D’acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, and Emmanuelle Jousselin. 2023. “Co-Obligate Symbioses Have Repeatedly Evolved across Aphids, but Partner Identity and Nutritional Contributions Vary across Lineages.” bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559. McCutcheon, John P., and Nancy A. Moran. 2012. “Extreme Genome Reduction in Symbiotic Bacteria.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670. | Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineages | Alejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Aphids are a large family of phloem-sap feeders. They typically rely on a single bacterial endosymbiont, <em>Buchnera aphidicola</em>, to supply them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. This association ... |  | Genome Evolution, Other, Species interactions | Olivier Tenaillon | 2022-11-16 10:13:37 | View | |

18 Jan 2017

POSTPRINT

Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an InsectAlem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564Culture in BumblebeesRecommended by Caroline Nieberding and Jacques J. M. van AlphenThis is an original paper [1] addressing the question whether cultural transmission occurs in insects and studying the mechanisms of such transmission. Often, culture-like phenomena require relatively sophisticated learning mechanisms, for example imitation and/or teaching. In insects, seemingly complex processes of social information acquisition, can sometimes instead be mediated by relatively simple learning mechanisms suggesting that cultural processes may not necessarily require sophisticated learning abilities. An important quality of this paper is to describe neatly the experimental protocols used for such typically complex behavioural analyses, providing a detailed understanding of the results while it remains a joy to read. This becomes rare in high impact journals. In a clever experimental design, individual bumblebees are trained to pull an artificial flower from under a Plexiglas table to get access to a reward, by pulling a string attached to the flower. Individuals that have learnt this task are then shown to inexperienced bees while performing this task. This results in a large proportion of the inexperienced observers learning to pull the string and getting access to the reward. Finally, the authors could then document the spread of the string pulling skill amongst other workers in the colony. Even when the originally trained individuals had died, the skill of string-pulling persisted in the colony, as long as they were challenged with the task. This shows that cultural transmission takes place within a colony. The authors provide evidence that the transmission of this behavior among individuals relies on a mix of social learning by local enhancement (bees were attracted to the location where they had observed a demonstrator) and of non-social, individual learning (pulling the string is learned by trial and errors and not by direct imitation of the conspecific). Data also show that simple associative mechanisms are enough and that stimulus enhancement was involved (bees were attracted to the string when its location was concordant with that during prior observation). The cleverly designed experiments use a paradigm (string-pulling) which has often been used to investigate cognitive abilities in vertebrates. Comparison with such studies indicate that bees, in some aspects of their learning, may not be different from birds, dogs, or apes as they also relied on the perceptual feedback provided by their actions, resulting in target movement to learn string pulling. The results of the study suggest that the combination of relatively simple forms of social learning and trial-and-error learning can mediate the acquisition of new skills and that bumblebees possess the essential cognitive elements for cultural transmission and in a broader sense, that the capacity of culture may be present within most animals. Can we expect behavioural innovation such as string pulling to occur in nature? Bombus terrestris colonies can reach a total of several hundreds foragers. In the experiments, foragers needed on average 5 rounds of observations with different demonstrators to learn how to pull the string. As individuals forage in a meadow full of flowers and conspecifics, transmission of behavioural innovations by repeated observations shouldn’t strike us as something impossible. Would the behavior survive through the winter? Bumblebee colonies are seasonal in northern areas and in the Mediterranean area but tropical species persists for several years. In seasonal species, all the workers die before winter and only new queens overwinter. So there is no possibility for seasonal foragers to transmit the technique overwinter. Only queens could potentially transmit it to new foragers in spring. However flowers are different in autumn and spring. Therefore, what queens have learnt about flowers in autumn would unlikely be useful in spring (providing that they can remember it). However there is no reason why the technique couldn't be transmitted from a colony to another between spring to autumn. Such transmission of new behaviour would more easily persist in perennial social insect colonies, like honeybees. Importantly, the bees used in these experiments came from a company whose rearing conditions are unknown, and only a few colonies were used for each experiment. As learning ability has a genetic basis [2-3], colonies differ in their ability to learn [4]. In this regard, the authors showed variation between individual bumblebees and between bumblebee colonies in learning ability. Hence, we would wish to know more about the level of genetic diversity in the wild, and of genetic differentiation between tested colonies (were they independent replicates?), to extrapolate the results to what may happen in the wild. Excitingly, the authors found 2 true innovators among the >400 individuals that were tested at least once for 5 min who would solve such a task without stepwise training or observation of skilled demonstrators, showing that behavioural innovation can occur in very small numbers of individuals, provided that an ecological trigger is provided (food reward). Hence this study shows that all ingredients for the long proposed “social heredity” theory proposed by Baldwin in 1896 are available in this organism, suggesting that social transmission of behavioural innovations could technically act as an additional mechanism for adaptive evolution [5], next to genetic evolution that may take longer to produce adaptive evolution. The question remains whether the behavioural innovations are arising from standing genetic variation in the bees, or do not need a firm genetic background to appear. References [1] Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L. 2016. Associative mechanisms allow for social learning and cultural transmission of string pulling in an insect. PloS Biology 14:e1002564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564 [2] Mery F, Kawecki TJ. 2002. Experimental evolution of learning ability in fruit flies. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 99:14274-14279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371199 [3] Mery F, Belay AT, So AKC, Sokolowski MB, Kawecki TJ. 2007. Natural polymorphism affecting learning and memory in Drosophila. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA 104:13051-13055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702923104 [4] Raine NE, Chittka L. 2008. The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumble-bees. Proceeding of the Royal Society of London 275: 803-808. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1652 [5] Baldwin JM. 1896. A New Factor in Evolution. American Naturalist 30:441-451 and 536-553. doi: 10.1086/276408 | Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural Transmission of String Pulling in an Insect | Alem S, Perry CJ, Zhu X, Loukola OJ, Ingraham T, Søvik E, Chittka L | Social insects make elaborate use of simple mechanisms to achieve seemingly complex behavior and may thus provide a unique resource to discover the basic cognitive elements required for culture, i.e., group-specific behaviors that spread from “inn... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Non Genetic Inheritance, Phenotypic Plasticity | Caroline Nieberding | 2017-01-18 10:49:03 | View | |

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

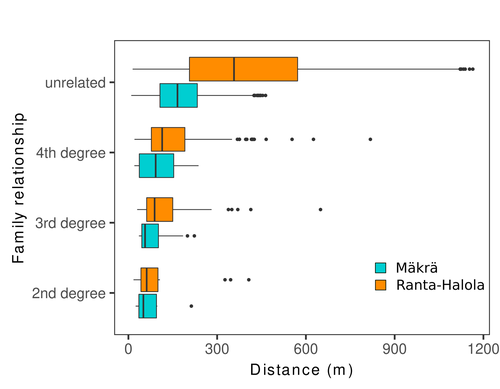

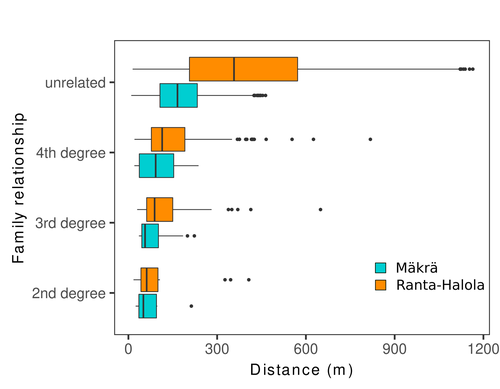

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

19 Feb 2018

Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY systemAline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/179044Dosage compensation by upregulation of maternal X alleles in both males and females in young plant sex chromosomesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Judith Mank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes evolve as recombination is suppressed between the X and Y chromosomes. The loss of recombination on the sex-limited chromosome (the Y in mammals) leads to degeneration of both gene expression and gene content for many genes [1]. Loss of gene expression or content from the Y chromosome leads to differences in gene dose between males and females for X-linked genes. Because expression levels are often correlated with gene dose [2], these hemizygous genes have a lower expression levels in the heterogametic sex. This in turn disrupts the stoichiometric balance among genes in protein complexes that have components on both the sex chromosomes and autosomes [3], which could have serious deleterious consequences for the heterogametic sex. References | Genomic imprinting mediates dosage compensation in a young plant XY system | Aline Muyle, Niklaus Zemp, Cecile Fruchard, Radim Cegan, Jan Vrana, Clothilde Deschamps, Raquel Tavares, Franck Picard, Roman Hobza, Alex Widmer, Gabriel Marais | <p>During the evolution of sex chromosomes, the Y degenerates and its expression gets reduced relative to the X and autosomes. Various dosage compensation mechanisms that recover ancestral expression levels in males have been described in animals.... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Tatiana Giraud | 2017-09-20 20:39:46 | View | |

12 Jun 2018

Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticaeAlison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri https://doi.org/10.1101/240127Maternal effects in sex-ratio adjustmentRecommended by Dries Bonte based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersOptimal sex ratios have been topic of extensive studies so far. Fisherian 1:1 proportions of males and females are known to be optimal in most (diploid) organisms, but many deviations from this golden rule are observed. These deviations not only attract a lot of attention from evolutionary biologists but also from population ecologists as they eventually determine long-term population growth. Because sex ratios are tightly linked to fitness, they can be under strong selection or plastic in response to changing demographic conditions. Hamilton [1] pointed out that an equality of the sex ratio breaks down when there is local competition for mates. Competition for mates can be considered as a special case of local resource competition. In short, this theory predicts females to adjust their offspring sex ratio conditional on cues indicating the level of local mate competition that their sons will experience. When cues indicate high levels of LMC mothers should invest more resources in the production of daughters to maximise their fitness, while offspring sex ratios should be closer to 50:50 when cues indicate low levels of LMC. References [1] Hamilton, W. D. (1967). Extraordinary Sex Ratios. Science, 156(3774), 477–488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 | Transgenerational cues about local mate competition affect offspring sex ratios in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae | Alison B. Duncan, Cassandra Marinosci, Céline Devaux, Sophie Lefèvre, Sara Magalhães, Joanne Griffin, Adeline Valente, Ophélie Ronce, Isabelle Olivieri | <p style="text-align: justify;">In structured populations, competition between closely related males for mates, termed Local Mate Competition (LMC), is expected to select for female-biased offspring sex ratios. However, the cues underlying sex all... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Dries Bonte | 2017-12-29 16:10:32 | View | |

09 Nov 2018

Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparumAmelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kounbobr R Dabire, Thierry Lefevre https://doi.org/10.1101/207183Malaria host manipulation increases probability of mosquitoes feeding on humansRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Olivier Restif, Ricardo S. Ramiro and 1 anonymous reviewerParasites can manipulate their host’s behaviour to ensure their own transmission. These manipulated behaviours may be outside the range of ordinary host activities [1], or alter the crucial timing and/or location of a host’s regular activity. Vantaux et al show that the latter is true for the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum [2]. They demonstrate that three species of Anopheles mosquito were 24% more likely to choose human hosts, rather than other vertebrates, for their blood feed when they harboured transmissible stages (sporozoites) compared to when they were uninfected, or infected with non-transmissible malaria parasites [2]. Host choice is crucial for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to complete its life-cycle, as their host range is much narrower than the mosquito’s for feeding; P. falciparum can only develop in hominids, or closely related apes [3]. References [1] Thomas, F., Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., Martin, G., Manu, C., Durand, P., & Renaud, F. (2002). Do hairworms (Nematomorpha) manipulate the water seeking behaviour of their terrestrial hosts? Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15(3), 356–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00410.x | Field evidence for manipulation of mosquito host selection by the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum | Amelie Vantaux, Franck Yao, Domonbabele FdS Hien, Edwige Guissou, Bienvenue K Yameogo, Louis-Clement Gouagna, Didier Fontenille, Francois Renaud, Frederic Simard, Carlo Constantini, Frederic Thomas, Karine Mouline, Benjamin Roche, Anna Cohuet, Kou... | <p>Whether the malaria parasite *Plasmodium falciparum* can manipulate mosquito host choice in ways that enhance parasite transmission toward human is unknown. We assessed the influence of *P. falciparum* on the blood-feeding behaviour of three of... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2018-02-28 09:12:14 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradientAndrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine https://doi.org/10.1101/236646One (more) step towards a dynamic view of the Latitudinal Diversity GradientRecommended by Joaquín Hortal and Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers

The Latitudinal Diversity Gradient (LDG) has fascinated natural historians, ecologists and evolutionary biologists ever since [1] described it about 200 years ago [2]. Despite such interest, agreement on the origin and nature of this gradient has been elusive. Several tens of hypotheses and models have been put forward as explanations for the LDG [2-3], that can be grouped in ecological, evolutionary and historical explanations [4] (see also [5]). These explanations can be reduced to no less than 26 hypotheses, which account for variations in ecological limits for the establishment of progressively larger assemblages, diversification rates, and time for species accumulation [5]. Besides that, although in general the tropics hold more species, different taxa show different shapes and rates of spatial variation [6], and a considerable number of groups show reverse patterns, with richer assemblages in cold temperate regions (see e.g. [7-9]). References | Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient | Andrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine | <p>Biodiversity currently peaks at the equator, decreasing toward the poles. Growing fossil evidence suggest that this hump-shaped latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG) has not been persistent through time, with similar species diversity across lat... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Joaquín Hortal | 2017-12-20 14:58:01 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer