Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

06 Sep 2022

Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonadsJulie Jaquiery, Jean-Christophe Simon, Stephanie Robin, Gautier Richard, Jean Peccoud, Helene Boulain, Fabrice Legeai, Sylvie Tanguy, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Gael Letrionnaire https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.453080Sex-biased gene expression is not tissue-specific in Pea AphidsRecommended by Charles Baer and Tanja Schwander based on reviews by Ann Kathrin Huylmans and 1 anonymous reviewerSexual antagonism (SA), wherein the fitness interests of the sexes do not align, is inherent to organisms with two (or more) sexes. SA leads to intra-locus sexual conflict, where an allele that confers higher fitness in one sex reduces fitness in the other [1, 2]. This situation leads to what has been referred to as "gender load", resulting from the segregation of SA alleles in the population. Gender load can be reduced by the evolution of sex-specific (or sex-biased) gene expression. A specific prediction is that gene-duplication can lead to sub- or neo-functionalization, in which case the two duplicates partition the function in the different sexes. The conditions for invasion by a SA allele differ between sex-chromosomes and autosomes, leading to the prediction that (in XY or XO systems) the X should accumulate recessive male-favored alleles and dominant female-favored alleles; similar considerations apply in ZW systems ([3, but see 4]. Aphids present an interesting special case, for several reasons: they have XO sex-determination, and three distinct reproductive morphs (sexual females, parthenogenetic females, and males). Previous theoretical work by the lead author predict that the X should be optimized for male function, which was borne out by whole-animal transcriptome analysis [5]. Here [6], the authors extend that work to investigate “tissue”-specific (heads, legs and gonads), sex-specific gene expression. They argue that, if intra-locus SA is the primary driver of sex-biased gene expression, it should be generally true in all tissues. They set up as an alternative the possibility that sex-biased gene expression could also be driven by dosage compensation. They cite references supporting their argument that "dosage compensation (could be) stronger in the brain", although the underlying motivation for that argument appears to be based on empirical evidence rather than theoretical predictions. At any rate, the results are clear: all tissues investigated show masculinization of the X. Further, X-linked copies of gene duplicates were more frequently male-biased than duplicated autosomal genes or X-linked single-copy genes. To sum up, this is a nice empirical study with clearly interpretable (and interpreted) results, the most obvious of which is the greater sex-biased expression in sexually-dimorphic tissues. Unfortunately, as the authors emphasize, there is no general theory by which SA, variable dosage-compensation, and meiotic sex chromosome inactivation can be integrated in a predictive framework. It is to be hoped that empirical studies such as this one will motivate deeper and more general theoretical investigations. References [1] Rice WR, Chippindale AK (2001) Intersexual ontogenetic conflict. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 14: 685-693. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00319.x [2] Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF (2009) Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol Evol 24: 280-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005 [3] Rice WR. (1984) Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38: 735-742. https://doi.org/10.1086/595754 [4] Fry JD (2010) The genomic location of sexually antagonistic variation: some cautionary comments. Evolution 64: 1510-1516. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1558-5646.2009.00898.x [5] Jaquiéry J, Rispe C, Roze D, Legeai F, Le Trionnaire G, Stoeckel S, et al. (2013) Masculinization of the X Chromosome in the Pea Aphid. PLoS Genetics 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003690 [6] Jaquiéry J, Simon J-C, Robin S, Richard G, Peccoud J, Boulain H, Legeai F, Tanguy S, Prunier-Leterme N, Le Trionnaire G (2022) Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonads. bioRxiv, 2021.08.13.453080, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.13.453080 | Masculinization of the X-chromosome in aphid soma and gonads | Julie Jaquiery, Jean-Christophe Simon, Stephanie Robin, Gautier Richard, Jean Peccoud, Helene Boulain, Fabrice Legeai, Sylvie Tanguy, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Gael Letrionnaire | <p>Males and females share essentially the same genome but differ in their optimal values for many phenotypic traits, which can result in intra-locus conflict between the sexes. Aphids display XX/X0 sex chromosomes and combine unusual X chromosome... |  | Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Charles Baer | 2021-08-16 08:56:08 | View | |

11 Jul 2022

Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitismLeo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759Give them some space: how spatial structure affects the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosisRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Eva Kisdi and 3 anonymous reviewers

The evolution of mutualistic symbiosis is a puzzle that has fascinated evolutionary ecologist for quite a while. Data on transitions between symbiotic bacterial ways of life has evidenced shifts from mutualism towards parasitism and vice versa (Sachs et al., 2011), so there does not seem to be a strong determinism on those transitions. From the host’s perspective, mutualistic symbiosis implies at the very least some form of immune tolerance, which can be costly (e.g. Sorci, 2013). Empirical approaches thus raise very important questions: How can symbiosis turn from parasitism into mutualism when it seemingly needs such a strong alignment of selective pressures on both the host and the symbiont? And yet why is mutualistic symbiosis so widespread and so important to the evolution of macro-organisms (Margulis, 1998)? While much of the theoretical literature on the evolution of symbiosis and mutualism has focused on either the stability of such relationships when non-mutualists can invade the host-symbiont system (e.g. Ferrière et al., 2007) or the effect of the mode of symbiont transmission on the evolutionary dynamics of mutualism (e.g. Genkai-Kato and Yamamura, 1999), the question remains whether and under which conditions parasitic symbiosis can turn into mutualism in the first place. Earlier results suggested that spatial demographic heterogeneity between host populations could be the leading determinant of evolution towards mutualism or parasitism (Hochberg et al., 2000). Here, Ledru et al. (2022) investigate this question in an innovative way by simulating host-symbiont evolutionary dynamics in a spatially explicit context. Their hypothesis is intuitive but its plausibility is difficult to gauge without a model: Does the evolution towards mutualism depend on the ability of the host and symbiont to evolve towards close-range dispersal in order to maintain clusters of efficient host-symbiont associations, thus outcompeting non-mutualists? I strongly recommend reading this paper as the results obtained by the authors are very clear: competition strength and the cost of dispersal both affect the likelihood of the transition from parasitism to mutualism, and once mutualism has set in, symbiont trait values clearly segregate between highly dispersive parasites and philopatric mutualists. The demonstration of the plausibility of their hypothesis is accomplished with brio and thoroughness as the authors also examine the conditions under which the transition can be reversed, the impact of the spatial range of competition and the effect of mortality. Since high dispersal cost and strong, long-range competition appear to be the main factors driving the evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosis, now is the time for empiricists to start investigating this question with spatial structure in mind. References Ferrière, R., Gauduchon, M. and Bronstein, J. L. (2007) Evolution and persistence of obligate mutualists and exploiters: competition for partners and evolutionary immunization. Ecology Letters, 10, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01008.x Genkai-Kato, M. and Yamamura, N. (1999) Evolution of mutualistic symbiosis without vertical transmission. Theoretical Population Biology, 55, 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1998.1407 Hochberg, M. E., Gomulkiewicz, R., Holt, R. D. and Thompson, J. N. (2000) Weak sinks could cradle mutualistic symbioses - strong sources should harbour parasitic symbioses. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13, 213-222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00157.x Ledru L, Garnier J, Rohr M, Noûs C and Ibanez S (2022) Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism. bioRxiv, 2021.08.18.456759, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.18.456759 Margulis, L. (1998) Symbiotic planet: a new look at evolution, Basic Books, Amherst. Sachs, J. L., Skophammer, R. G. and Regus, J. U. (2011) Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 10800-10807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100304108 Sorci, G. (2013) Immunity, resistance and tolerance in bird–parasite interactions. Parasite Immunology, 35, 350-361. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12047 | Mutualists construct the ecological conditions that trigger the transition from parasitism | Leo Ledru, Jimmy Garnier, Matthias Rohr, Camille Nous, Sebastien Ibanez | <p>The evolution of mutualism between hosts and initially parasitic symbionts represents a major transition in evolution. Although vertical transmission of symbionts during host reproduction and partner control both favour the stability of mutuali... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Francois Massol | 2021-08-20 12:25:40 | View | |

25 Jan 2023

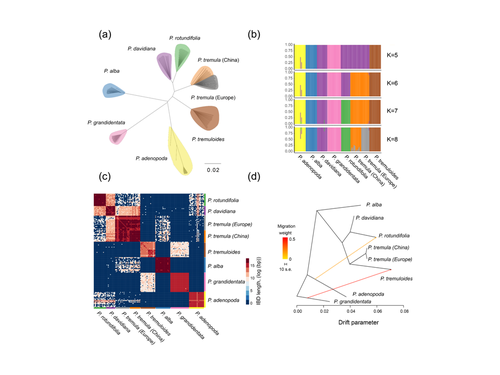

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View | |

30 Mar 2023

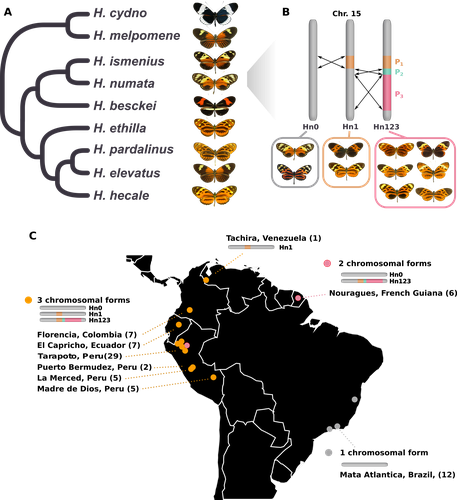

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterflyMaría Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, Mathieu Joron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea. The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale. Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding. REFERENCES Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348 | Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly | María Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Selection shapes genetic diversity around target mutations, yet little is known about how selection on specific loci affects the genetic trajectories of populations, including their genomewide patterns of diversity ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Chris Jiggins | 2021-10-13 17:54:33 | View | |

29 Nov 2022

Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic dataVitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133Inference of genome-wide processes using temporal population genomic dataRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio and 2 anonymous reviewers

Evolutionary genomics, and population genetics in particular, aim to decipher the respective influence of neutral and selective forces shaping genetic polymorphism in a species/population. This is a much-needed requirement before scanning genome data for footprints of species adaptation to their biotic and abiotic environment (Johri et al. 2022). In general, we would like to quantify the proportion of the genome evolving neutrally and under selective (positive, balancing and negative) pressures (Kern and Hahn 2018, Johri et al. 2021). We thus need to understand patterns of linked selection along the genome, that is how the distribution of genetic polymorphisms is shaped by selected sites and the recombination landscape. The present contribution by Pavinato et al. (2022) provides an additional method in the population genomics toolbox to quantify the extent of linked positive and negative selection using temporal data. The availability of genomics data for model and non-model species has led to improvement of the modeling framework for demography and selection (Johri et al. 2022), but also new inference methods making use of the full genome data based on the Sequential Markovian Coalescent (SMC, Li and Durbin 2011), Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC, Jay et al. 2019), ABC and machine learning (Pudlo et al. 2016, Raynal et al. 2019) or Deep Learning (Sanchez et al. 2021). These methods are based on one sample in time and the use of the coalescent theory to reconstruct the past (demographic) history. However, it is also possible to obtain for many species temporal data sampled over several time points. For species with short generation time (in experimental evolution or monitored populations), one can sample a population every couple of generations as exemplified with Drosophila melanogaster (Bergland et al. 2010). For species with longer generation times that cannot be easily regularly sampled in time, it becomes possible to sequence available specimens from museums (e.g. Cridland et al. 2018) or ancient DNA samples. Methods using temporal data are based on the classical population genomics assumption that demography (migration, population subdivision, population size changes) leaves a genome-wide signal, while selection leaves a localized signal in the close vicinity of the causal mutation. Several methods do assess the demography of a population (change in effective population size, Ne, in time) using temporal data (e.g. Jorde and Ryman 2007) which can be used to calibrate the detection of loci under strong positive selection (Foll et al. 2014). Recently Buffalo and Coop (2020) used genome-wide covariance between allele frequency changes across time samples (and across replicates) to quantify the effects of linked selection over short timescales. In the present contribution, Pavinato et al. (2022) make use of temporal data to draw the joint estimation of demographic and selective parameters using a simulation-based method (ABC-Random Forests). This study by Pavinato et al. (2022) builds a framework allowing to infer the census size of the population in time (N) separately from the effect of genetic drift, which is determined by change in effective population size (Ne) in time, as well estimates of genome-wide parameters of selection. In a nutshell, the authors use a forward simulator and summarize genome data by genomic windows using classic statistics (nucleotide diversity, Tajima’s D, FST, heterozygosity) between time samples and for each sample. They specifically use the distributions (higher moments) of these statistics among all windows. The authors combine as input for the ABC-RF, vectors of summary statistics, model parameters and five latent variables: Ne, the ratio Ne/N, the number of beneficial mutations under strong selection, the average selection coefficient of strongly selected mutations, and the average substitution load. Indeed, the authors are interested in three different types of selection components: 1) the adaptive potential of a population which is estimated as the population mutation rate of beneficial mutations (θb), 2) the number of mutations under strong selection (irrespective of whether they reached fixation or not), and 3) the overall population fitness which is a function of the genetic load. In other words, the novelty of this method is not to focus on the detection of loci under selection, but to infer key parameters/distributions summarizing the genome-wide signal of demography and (positive and negative) selection. As a proof of principle, the authors then apply their method to a dataset of feral populations of honey bees (Apis mellifera) collected in California across many years and recovered from Museum samples (Cridland et al. 2018). The approach yields estimates of Ne which are on the same order of magnitude of previous estimates in hymenopterans, and the authors discuss why the different populations show various values of Ne and N which can be explained by different history of admixture with wild but also domesticated lineages of bees. This study focuses on quantifying the genome-wide joint footprints of demography, and strong positive and negative selection to determine which proportion of the genome evolves neutrally or not. Further application of this method can be anticipated, for example, to study species with ecological and life-history traits which generate discrepancies between census size and Ne, for example for plants with selfing or seed banking (Sellinger et al. 2020), and for which the genome-wide effect of linked selection is not fully understood. References Johri P, Aquadro CF, Beaumont M, Charlesworth B, Excoffier L, Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD, Lynch M, McVean G, Payseur BA, Pfeifer SP, Stephan W, Jensen JD (2022) Recommendations for improving statistical inference in population genomics. PLOS Biology, 20, e3001669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001669 Kern AD, Hahn MW (2018) The Neutral Theory in Light of Natural Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy092 Johri P, Riall K, Becher H, Excoffier L, Charlesworth B, Jensen JD (2021) The Impact of Purifying and Background Selection on the Inference of Population History: Problems and Prospects. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 2986–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab050 Pavinato VAC, Mita SD, Marin J-M, Navascués M de (2022) Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data. bioRxiv, 2021.03.12.435133, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.12.435133 Li H, Durbin R (2011) Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475, 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 Jay F, Boitard S, Austerlitz F (2019) An ABC Method for Whole-Genome Sequence Data: Inferring Paleolithic and Neolithic Human Expansions. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36, 1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz038 Pudlo P, Marin J-M, Estoup A, Cornuet J-M, Gautier M, Robert CP (2016) Reliable ABC model choice via random forests. Bioinformatics, 32, 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv684 Raynal L, Marin J-M, Pudlo P, Ribatet M, Robert CP, Estoup A (2019) ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35, 1720–1728. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F (2021) Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, 21, 2645–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224 Bergland AO, Behrman EL, O’Brien KR, Schmidt PS, Petrov DA (2014) Genomic Evidence of Rapid and Stable Adaptive Oscillations over Seasonal Time Scales in Drosophila. PLOS Genetics, 10, e1004775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004775 Cridland JM, Ramirez SR, Dean CA, Sciligo A, Tsutsui ND (2018) Genome Sequencing of Museum Specimens Reveals Rapid Changes in the Genetic Composition of Honey Bees in California. Genome Biology and Evolution, 10, 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evy007 Jorde PE, Ryman N (2007) Unbiased Estimator for Genetic Drift and Effective Population Size. Genetics, 177, 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.107.075481 Foll M, Shim H, Jensen JD (2015) WFABC: a Wright–Fisher ABC-based approach for inferring effective population sizes and selection coefficients from time-sampled data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12280 Buffalo V, Coop G (2020) Estimating the genome-wide contribution of selection to temporal allele frequency change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 20672–20680. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919039117 Sellinger TPP, Awad DA, Moest M, Tellier A (2020) Inference of past demography, dormancy and self-fertilization rates from whole genome sequence data. PLOS Genetics, 16, e1008698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008698 | Joint inference of adaptive and demographic history from temporal population genomic data | Vitor A. C. Pavinato, Stéphane De Mita, Jean-Michel Marin, Miguel de Navascués | <p style="text-align: justify;">Disentangling the effects of selection and drift is a long-standing problem in population genetics. Simulations show that pervasive selection may bias the inference of demography. Ideally, models for the inference o... |  | Adaptation, Population Genetics / Genomics | Aurelien Tellier | 2021-10-20 09:41:26 | View | |

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

02 Nov 2022

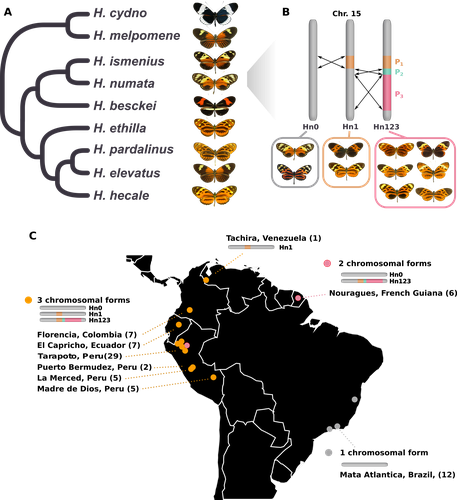

Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndromeMathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450Demographic effects may affect adaptation to islandsRecommended by Emma Berdan based on reviews by Steven Fiddaman and 3 anonymous reviewersThe unique challenges associated with living on an island often result in organisms displaying a specific suite of traits commonly referred to as “island syndrome” (Adler and Levins, 1994; Burns, 2019; Baeckens and Van Damme, 2020). Large phenotypic shifts such as changes in size (e.g. shifts to gigantism or dwarfism, Lomolino, 2005) or coloration (Doutrelant et al., 2016) abound in the literature. However, less obvious phenotypes may also play a key role in adaptation to islands. One such trait, reduced immune function, has important implications for the future of island populations in the face of anthropogenic-induced changes. Due to lower parasite pressure caused by a less diverse and less virulent parasite population, island hosts may show a decrease in immune defenses (Beadell et al., 2006; Pérez‐Rodríguez et al., 2013). However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as many studies have found ambiguous or conflicting results (Matson, 2006; Illera et al., 2015). While most previous work has examined various immunological parameters (e.g., antibody concentrations), here, Barthe et al. (2022) take the novel approach of examining molecular signatures of immune genes. Using comparative genomic data from 34 different species of birds the authors examine the ratio of synonymous substitutions (i.e., not changing an amino acid) to non-synonymous substitutions (i.e., changing an amino acid) in innate and acquired immune genes (Pn/Ps ratio). Because population sizes on islands are lower which will affect molecular evolution, they compare these results to data from 97 control genes. Assuming relaxed selection on islands predicts that the difference between the Pn/Ps ratio of immune genes and of control genes (ΔPn/Ps) is greater in island species compared to mainland ones. As with previous work the authors found that the results differ depending on the category of immune genes. Both forms of innate defense: beta-defensins and Toll-like receptors did not show higher ΔPn/Ps for island populations. As these genes still have a higher Pn/Ps than control genes, the authors argue these results are in line with these genes being under purifying selection but lacking an “island effect”. Instead, the authors argue that demographic effects (i.e., reductions in Ne) may lead to the decreased immunity documented in other studies. In contrast, there was a reduction in Pn/Ps in MHC II genes, known to be under balancing selection. This reduction was stronger in island species and thus the authors argue that this is the only class of genes where a role for relaxed selection can be invoked. Together these results demonstrate that the changes in immunity experienced by island species are complex and that different categories of immune genes can experience different selective pressures. By including control genes in their study, they particularly highlight the importance of accounting for shifts in Ne when examining patterns of island species evolution. Hopefully, this kind of framework will be applied to other taxa to determine if these results are widespread or more specific to birds. References Adler GH, Levins R (1994) The Island Syndrome in Rodent Populations. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1086/418744 Baeckens S, Van Damme R (2020) The island syndrome. Current Biology, 30, R338–R339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029 Barthe M, Doutrelant C, Covas R, Melo M, Illera JC, Tilak M-K, Colombier C, Leroy T, Loiseau C, Nabholz B (2022) Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome. bioRxiv, 2021.11.21.469450, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450 Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Graves GR, Jhala YV, Peirce MA, Rahmani AR, Fonseca DM, Fleischer RC (2006) Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2935–2944. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3671 Burns KC (2019) Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379953 Doutrelant C, Paquet M, Renoult JP, Grégoire A, Crochet P-A, Covas R (2016) Worldwide patterns of bird colouration on islands. Ecology Letters, 19, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12588 Illera JC, Fernández-Álvarez Á, Hernández-Flores CN, Foronda P (2015) Unforeseen biogeographical patterns in a multiple parasite system in Macaronesia. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1858–1870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12548 Lomolino MV (2005) Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01314.x Matson KD (2006) Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 Pérez-Rodríguez A, Ramírez Á, Richardson DS, Pérez-Tris J (2013) Evolution of parasite island syndromes without long-term host population isolation: parasite dynamics in Macaronesian blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 22, 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12084 | Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome | Mathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Shared ecological conditions encountered by species that colonize islands often lead to the evolution of convergent phenotypes, commonly referred to as “island syndrome”. Reduced immune functions have been previousl... |  | Adaptation, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emma Berdan | 2021-11-28 11:01:31 | View | |

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View | |

16 Dec 2022

Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depressionDiala Abu Awad, Donald Waller https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022Pseudo-overdominance: how linkage and selection can interact and oppose to purging of deleterious mutations.Recommended by Sylvain Glémin based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Yaniv Brandvain, Lei Zhao and 1 anonymous reviewer

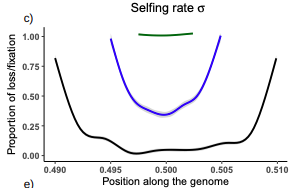

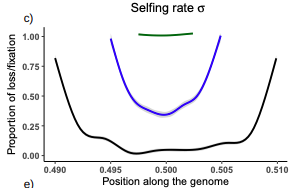

Most mutations affecting fitness are deleterious and they have many evolutionary consequences. The dynamics and consequences of deleterious mutations are a long-standing question in evolutionary biology and a strong theoretical background has already been developed, for example, to predict the mutation load, inbreeding depression or background selection. One of the classical results is that inbreeding helps purge partially recessive deleterious mutations by exposing them to selection in homozygotes. However, this mainly results from single-locus considerations. When interactions among several, more or less linked, deleterious mutations are taken into account, peculiar dynamics can emerge. One of them, called pseudo-overdominance (POD), corresponds to the maintenance in a population of two (or more) haplotype blocks composed of several recessive deleterious mutations in repulsion that mimics overdominance. Indeed, homozygote individuals for one of the haplotype blocks expose many deleterious mutations to selection whereas they are reciprocally masked in heterozygotes, leading to higher fitness of heterozygotes compared to both homozygotes. A related process, called associative overdominance (AOD) is the effect of such deleterious alleles in repulsion on the linked neutral variation that can be increased by AOD. Although this possibility has been recognized for a long time (Otha and Kimura 1969), it has been mainly considered an anecdotal process. Recently, both theoretical (Zhao and Charlesworth 2016) and genomic analyses (Gilbert et al. 2020) have renewed interest in such a process, suggesting that it could be important in weakly recombining regions of a genome. Donald Waller (2021) - one of the co-authors of the current work - also recently proposed that POD could be quantitatively important with broad implications, and could resolve some unexplained observations such as the maintenance of inbreeding depression in highly selfing species. Yet, a proper theoretical framework analysing the effect of inbreeding on POD was lacking. In this theoretical work, Diala Abu Awad and Donald Waller (2022) addressed this question through an elegant combination of analytical predictions and intensive multilocus simulations. They determined the conditions under which POD can be maintained and how long it could resist erosion by recombination, which removes the negative association between deleterious alleles (repulsion) at the core of the mechanism. They showed that under tight linkage, POD regions can persist for a long time and generate substantial segregating load and inbreeding depression, even under inbreeding, so opposing (for a while) to the purging effect. They also showed that background selection can affect the genomic structure of POD regions by rapidly erasing weak POD regions but maintaining strong POD regions (i.e with many tightly linked deleterious alleles). These results have several implications. They can explain the maintenance of inbreeding depression despite inbreeding (as anticipated by Waller 2021), which has implications for the evolution of mating systems. If POD can hardly emerge under high selfing, it can persist from an outcrossing ancestor long after the transition towards a higher selfing rate and could explain the maintenance of mixed mating systems(which is possible with true overdominance, see Uyenoyama and Waller 1991). The results also have implications for genomic analyses, pointing to regions of low or no recombination where POD could be maintained, generating both higher diversity and heterozygosity than expected and variance in fitness. As structural variations are likely widespread in genomes with possible effects on suppressing recombination (Mérot et al. 2020), POD regions should be checked more carefully in genomic analyses (see also Gilbert et al. 2020). Overall, this work should stimulate new theoretical and empirical studies, especially to assess how quantitatively strong and widespread POD can be. It also stresses the importance of properly considering genetic linkage genome-wide, and so the role of recombination landscapes in determining patterns of diversity and fitness effects. References

Awad DA, Waller D (2022) Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression. bioRxiv, 2021.12.16.473022, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.473022 Gilbert KJ, Pouyet F, Excoffier L, Peischl S (2020) Transition from Background Selection to Associative Overdominance Promotes Diversity in Regions of Low Recombination. Current Biology, 30, 101-107.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.063 Mérot C, Oomen RA, Tigano A, Wellenreuther M (2020) A Roadmap for Understanding the Evolutionary Significance of Structural Genomic Variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.002 Ohta T, Kimura M (1969) Linkage disequilibrium at steady state determined by random genetic drift and recurrent mutation. Genetics, 63, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/63.1.229 Uyenoyama MK, Waller DM (1991) Coevolution of self-fertilization and inbreeding depression II. Symmetric overdominance in viability. Theoretical Population Biology, 40, 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(91)90046-I Waller DM (2021) Addressing Darwin’s dilemma: Can pseudo-overdominance explain persistent inbreeding depression and load? Evolution, 75, 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14189 Zhao L, Charlesworth B (2016) Resolving the Conflict Between Associative Overdominance and Background Selection. Genetics, 203, 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188912 | Conditions for maintaining and eroding pseudo-overdominance and its contribution to inbreeding depression | Diala Abu Awad, Donald Waller | <p style="text-align: justify;">Classical models that ignore linkage predict that deleterious recessive mutations should purge or fix within inbred populations, yet inbred populations often retain moderate to high segregating load. True overdomina... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Glémin | 2022-01-04 12:15:35 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang