Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Mar 2023

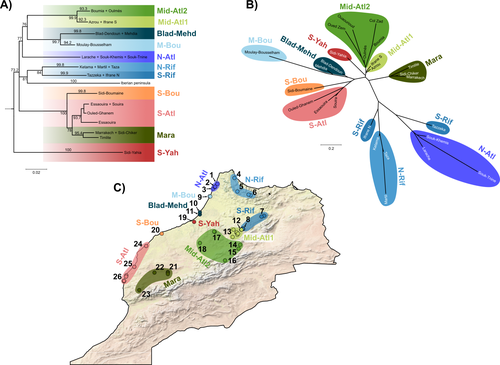

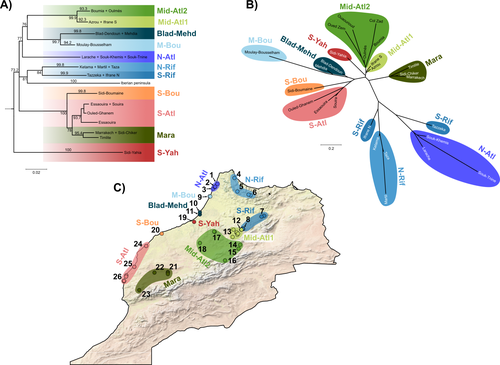

Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersalLoïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256The difficult task of partitioning the effects of vicariance and isolation by distance in poor dispersersRecommended by Eric Pante based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou

Partitioning the effects of vicariance and low dispersal has been a long-standing problem in historical biogeography and phylogeography. While the term “vicariance” refers to divergence in allopatry, caused by some physical (geological, geographical) or climatic barriers (e.g. Rosen 1978), isolation by distance refers to the genetic differentiation of remote populations due to the physical distance separating them, when the latter surpasses the scale of dispersal (Wright 1938, 1940, 1943). Vicariance and dispersal have long been considered as separate forces leading to separate scenarii of speciation (e.g. reviewed in Hickerson and Meyer 2008). Nevertheless, these two processes are strongly linked, as, for example, vicariance theory relies on the assumption that ancestral lineages were once linked by dispersal prior to physical or climatic isolation (Rosen 1978). Low dispersal and vicariance are not mutually exclusive, and distinguishing these two processes in heterogeneous landscapes, especially for poor dispersers, remains therefore a severe challenge. For example, low dispersal (and/or small population size) can give rise to geographic patterns consistent with a phylogeographic break and be mistaken for geographic isolation (Irwin 2002, Kuo and Avise 2005). The study of Rancilliac and colleagues (2023) is at the heart of this issue. It focuses on a nominal lizard species, the red-tailed spiny-footed lizard (Acanthodactylus erythrurus, Squamata: Lacertidae), which has a wide spatial distribution (from the Maghreb to the Iberian Peninsula), is found in a variety of different habitats, and has a wide range of morphological traits that do not always correlate with phylogeny. The main question is the following: have “the morphological and ecological diversification of this group been produced by vicariance and lineage diversification, or by local adaptation in the face of historical gene flow?” To tackle this question, the authors used sequence data from multiple mitochondrial and nuclear markers and a nested analysis workflow integrating phylogeography, multiple correspondence analyses and a relatively novel approach to IBD testing (Hausdorf & Henning, 2020). The latter is based on regression analysis and was shown to be less prone to error than the traditional (partial) Mantel test. While this set of methods allowed the partitioning of the effect of isolation by distance and vicariance in shaping contemporary genetic diversity in red-tailed spiny-footed lizards, some of the evolutionary history of this species complex remains blurred by ongoing gene flow and admixture, retention of ancestral polymorphism, or selection. The lack of congruence between mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees once again warns us that proposing evolutionary scenarii based on individual gene trees is a risky business. References Hausdorf B, Hennig C (2020) Species delimitation and geography. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20, 950–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13184 Hickerson MJ, Meyer CP (2008) Testing comparative phylogeographic models of marine vicariance and dispersal using a hierarchical Bayesian approach. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 8, 322. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-322 Irwin DE (2002) Phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers to gene flow. Evolution, 56, 2383–2394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00164.x Kuo C-H, Avise JC (2005) Phylogeographic breaks in low-dispersal species: the emergence of concordance across gene trees. Genetica, 124, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10709-005-2095-y Rancilhac L, Miralles A, Geniez P, Mendez-Aranda D, Beddek M, Brito JC, Leblois R, Crochet P-A (2023) Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: An empirical attempt at separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal. bioRxiv, 2022.09.30.510256, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256 Rosen DE (1978) Vicariant Patterns and Historical Explanation in Biogeography. Systematic Biology, 27, 159–188. https://doi.org/10.2307/2412970 Wright, S (1938) Size of population and breeding structure in relation to evolution. Science 87:430-431. Wright S (1940) Breeding Structure of Populations in Relation to Speciation. The American Naturalist, 74, 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/280891 Wright S (1943) Isolation by distance. Genetics, 28, 114–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/28.2.114 | Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal | Loïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet | <p>Aim</p> <p>Discontinuity in the distribution of genetic diversity (often based on mtDNA) is usually interpreted as evidence for phylogeographic breaks, underlying vicariant units. However, a misleading signal of phylogeographic break can arise... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Eric Pante | Kevin Sánchez | 2022-10-05 13:11:28 | View |

26 Nov 2019

Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studiesJobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume https://doi.org/10.1101/656413Understanding the effects of linkage and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptationRecommended by Kathleen Lotterhos based on reviews by Pär Ingvarsson and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic correlations among traits are ubiquitous in nature. However, we still have a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of trait correlations. Some genetic correlations among traits arise because of pleiotropy - single mutations or genotypes that have effects on multiple traits. Other genetic correlations among traits arise because of linkage among mutations that have independent effects on different traits. Teasing apart the differential effects of pleiotropy and linkage on trait correlations is difficult, because they result in very similar genetic patterns. However, understanding these differential effects gives important insights into how ubiquitous pleiotropy may be in nature. References [1] Chebib, J. and Guillaume, F. (2019). Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies. bioRxiv, 656413, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/656413 | Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies | Jobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume | <p>Genetic correlations between traits may cause correlated responses to selection depending on the source of those genetic dependencies. Previous models described the conditions under which genetic correlations were expected to be maintained. Sel... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Kathleen Lotterhos | 2019-06-05 13:51:43 | View | |

05 Jun 2018

Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species poolsJoaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal https://doi.org/10.1101/149617Recent assembly of European biogeographic species poolRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersBiodiversity is unevenly distributed over time, space and the tree of life [1]. The fact that regions are richer than others as exemplified by the latitudinal diversity gradient has fascinated biologists as early as the first explorers travelled around the world [2]. Provincialism was one of the first general features of land biotic distributions noted by famous nineteenth century biologists like the phytogeographers J.D. Hooker and A. de Candolle, and the zoogeographers P.L. Sclater and A.R. Wallace [3]. When these explorers travelled among different places, they were struck by the differences in their biotas (e.g. [4]). The limited distributions of distinctive endemic forms suggested a history of local origin and constrained dispersal. Much biogeographic research has been devoted to identifying areas where groups of organisms originated and began their initial diversification [3]. Complementary efforts found evidence of both historical barriers that blocked the exchange of organisms between adjacent regions and historical corridors that allowed dispersal between currently isolated regions. The result has been a division of the Earth into a hierarchy of regions reflecting patterns of faunal and floral similarities (e.g. regions, subregions, provinces). Therefore a first ensuing question is: “how regional species pools have been assembled through time and space?”, which can be followed by a second question: “what are the ecological and evolutionary processes leading to differences in species richness among species pools?”. To address these questions, the study of Calatayud et al. [5] developed and performed an interesting approach relying on phylogenetic data to identify regional and sub-regional pools of European beetles (using the iconic ground beetle genus Carabus). Specifically, they analysed the processes responsible for the assembly of species pools, by comparing the effects of dispersal barriers, niche similarities and phylogenetic history. They found that Europe could be divided in seven modules that group zoogeographically distinct regions with their associated faunas, and identified a transition zone matching the limit of the ice sheets at Last Glacial Maximum (19k years ago). Deviance of species co-occurrences across regions, across sub-regions and within each region was significantly explained, primarily by environmental niche similarity, and secondarily by spatial connectivity, except for northern regions. Interestingly, southern species pools are mostly separated by dispersal barriers, whereas northern species pools are mainly sorted by their environmental niches. Another important finding of Calatayud et al. [5] is that most phylogenetic structuration occurred during the Pleistocene, and they show how extreme recent historical events (Quaternary glaciations) can profoundly modify the composition and structure of geographic species pools, as opposed to studies showing the role of deep-time evolutionary processes. The study of biogeographic assembly of species pools using phylogenies has never been more exciting and promising than today. Catalayud et al. [5] brings a nice study on the importance of Pleistocene glaciations along with geographical barriers and niche-based processes in structuring the regional faunas of European beetles. The successful development of powerful analytical tools in recent years, in conjunction with the rapid and massive increase in the availability of biological data (including molecular phylogenies, fossils, georeferrenced occurrences and ecological traits), will allow us to disentangle complex evolutionary histories. Although we still face important limitations in data availability and methodological shortcomings, the last decade has witnessed an improvement of our understanding of how historical and biotic triggers are intertwined on shaping the Earth’s stupendous biological diversity. I hope that the Catalayud et al.’s approach (and analytical framework) will help movement in that direction, and that it will provide interesting perspectives for future investigations of other regions. Applied to a European beetle radiation, they were able to tease apart the relative contributions of biotic (niche-based processes) versus abiotic (geographic barriers and climate change) factors. References [1] Rosenzweig ML. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | Pleistocene climate change and the formation of regional species pools | Joaquín Calatayud, Miguel Á. Rodríguez, Rafael Molina-Venegas, María Leo, José Luís Hórreo, Joaquín Hortal | <p>Despite the description of bioregions dates back from the origin of biogeography, the processes originating their associated species pools have been seldom studied. Ancient historical events are thought to play a fundamental role in configuring... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2017-06-14 07:30:32 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius eratoErika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.13.523799Impact of pollen-feeding on egg-laying and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in red postman butterfliesRecommended by Adriana Briscoe based on reviews by Carol Boggs, Caroline Mueller and 1 anonymous reviewerGrowth, development and reproduction in animals are all limited by dietary nutrients. Expansion of an organism’s diet to sources not accessible to closely related species reduces food competition, and eases the constraints of nutrient-limited diets. Adult butterflies are herbivorous insects known to feed primarily on nectar from flowers, which is rich in sugars but poor in amino acids. Only certain species in the genus Heliconius are known to also feed on pollen, which is especially rich in amino acids, and is known to prolong their lives by several months. The ability to digest pollen in Heliconius has been linked to specialized feeding behaviors (Krenn et al. 2009) and extra-oral digestion using enzymes, possibly including duplicated copies of cocoonase (Harpel et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2016 and 2018), a protease used by some moths to digest silk upon eclosion from their cocoons. In this reprint, Pinheiro de Castro and colleagues investigated the impact of artificial and natural diets on egg-laying ability, body weight, and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in adult Heliconius erato butterflies of both sexes. Previous studies (Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1981) in H. charithonia demonstrated that access to dietary pollen led to extended egg-laying ability among adult female butterflies compared to females deprived of pollen, and compared to Dryas iulia females which feed only on nectar. In the current study, Pinheiro de Castro et al. (2023) examine the impact of diet on both young and old H. erato, over a longer period of time than the earlier work, highlighting the importance of extending the time period over which effects are evaluated. In addition to extending egg-laying ability in older females, the authors found that pollen in the diet appeared to maintain older female body weight, presumably because the pollen contained nutrients depleted during egg-laying. The authors then investigated the effects of nutrition on the production of cyanogenic glycoside defenses. Heliconius are aposematic butterflies that sequester cyanide-forming defense chemicals from food plants as larvae or synthesize these compounds de novo. The authors found the abundance of cyanogenic glycosides to be significantly greater in butterflies with access to pollen, but again only in older females. Curiously, field studies of male and female H. charithonia butterflies found that females in the wild collected more pollen than males (Mendoza-Cuenca and Macías-Ordóñez 2005). Taken together, these new findings raise the intriguing possibility that females collect more pollen than males, in part, because pollen has a bigger impact on female survival and reproduction. A small limitation of the study is the use of wing length, rather than body weight, at the zero time point. But the trend is clear in both males and females, and it adds supporting detail to the efficacy of pollen feeding as an unusual strategy for increasing fertility and survival in Heliconius butterflies.

References | Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius erato | Erika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins | <p>Dietary shifts may act to ease energetic constraints and allow organisms to optimise life-history traits. Heliconius butterflies differ from other nectar-feeders due to their unique ability to digest pollen, which provides a reliable source of ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Adriana Briscoe | 2023-02-07 12:59:54 | View | |

10 Jul 2019

Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pestGeorgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/362129The scandalous pestRecommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersKoutsovoulos et al. [1] have generated and analysed the first population genomic dataset in root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Why is this interesting? For two major reasons. First, M. incognita has been documented to be apomictic, i.e., to lack any form of sex. This is a trait of major evolutionary importance, with implications on species adaptive potential. The study of genome evolution in asexuals is fascinating and has the potential to inform on the forces governing the evolution of sex and recombination. Even small amounts of sex, however, are sufficient to restore most of the population genetic properties of true sexuals [2]. Because rare events of sex can remain undetected in the field, to confirm asexuality in M. incognita using genomic data is an important step. The second reason why M. incognita is of interest is that this nematode is one of the most harmful pests currently living on earth. M. incognita feeds on the roots of many cultivated plants, including tomato, bean, and cotton, and has been of major agricultural importance for decades. A number of races were defined based on host specificity. These have played a key role in attempts to control the dynamic of M. incognita populations via crop rotations. Races and management strategies so far lack any genetic basis, hence the second major interest of this study. References [1] Koutsovoulos, G. D., Marques, E., Arguel, M. J., Duret, L., Machado, A. C. Z., Carneiro, R. M. D. G., Kozlowski, D. K., Bailly-Bechet, M., Castagnone-Sereno, P., Albuquerque, E. V., & Danchin, E. G. J. (2019). Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest. bioRxiv, 362129, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/362129 | Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest | Georgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin | <p>The most devastating nematodes to worldwide agriculture are the root-knot nematodes with Meloidogyne incognita being the most widely distributed and damaging species. This parasitic and ecological success seem surprising given its supposed obli... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | 2018-08-24 09:02:33 | View | ||

14 May 2020

Potential adaptive divergence between subspecies and populations of snapdragon plants inferred from QST – FST comparisonsSara Marin, Anaïs Gibert, Juliette Archambeau, Vincent Bonhomme, Mylène Lascoste and Benoit Pujol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3628168From populations to subspecies… to species? Contrasting patterns of local adaptation in closely-related taxa and their potential contribution to species divergenceRecommended by Emmanuelle Porcher based on reviews by Sophie Karrenberg, Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez and 1 anonymous reviewerElevation gradients are convenient and widely used natural setups to study local adaptation, particularly in these times of rapid climate change [e.g. 1]. Marin and her collaborators [2] did not follow the mainstream, however. Instead of tackling adaptation to climate change, they used elevation gradients to address another crucial evolutionary question [3]: could adaptation to altitude lead to ecological speciation, i.e. reproductive isolation between populations in spite of gene flow? More specifically, they examined how much local adaptation to environmental variation differed among closely-related, recently diverged subspecies. They studied several populations of two subspecies of snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), with adjacent geographical distributions. Using common garden experiments and the classical, but still useful, QST-FST comparison, they demonstrate contrasting patterns of local adaptation to altitude between the two subspecies, with several traits under divergent selection in A. majus striatum but none in A. majus pseudomajus. These differences in local adaptation may contribute to species divergence, and open many stimulating questions on the underlying mechanisms, such as the identity of environmental drivers or contribution of reproductive isolation involving flower color polymorphism. References [1] Anderson, J. T., and Wadgymar, S. M. (2020). Climate change disrupts local adaptation and favours upslope migration. Ecology letters, 23(1), 181-192. doi: 10.1111/ele.13427 | Potential adaptive divergence between subspecies and populations of snapdragon plants inferred from QST – FST comparisons | Sara Marin, Anaïs Gibert, Juliette Archambeau, Vincent Bonhomme, Mylène Lascoste and Benoit Pujol | <p>Phenotypic divergence among natural populations can be explained by natural selection or by neutral processes such as drift. Many examples in the literature compare putatively neutral (FST) and quantitative genetic (QST) differentiation in mult... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Morphological Evolution, Quantitative Genetics | Emmanuelle Porcher | 2018-08-05 15:34:30 | View | |

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View | |

13 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

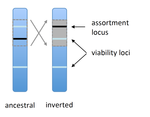

Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversionsDagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M 10.1111/evo.12954The spread of chromosomal inversions as a mechanism for reinforcementRecommended by Denis Roze and Thomas Broquet

Several examples of chromosomal inversions carrying genes affecting mate choice have been reported from various organisms. Furthermore, inversions are also frequently involved in genetic isolation between populations or species. Past work has shown that inversions can spread when they capture not only some loci involved in mate choice but also loci involved in incompatibilities between hybridizing populations [1]. In this new paper [2], the authors derive analytical approximations for the selection coefficient associated with an inversion suppressing recombination between a locus involved in mate choice and one (or several) locus involved in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities. Two mechanisms for mate choice are considered: assortative mating based on the allele present at a single locus, or a trait-preference model where one locus codes for the trait and another for the preference. The results show that such an inversion is generally favoured, the selective advantage associated with the inversion being strongest when hybridization is sufficiently frequent. Assuming pairwise epistatic interactions between loci involved in incompatibilities, selection for the inversion increases approximately linearly with the number of such loci captured by the inversion. This paper is a good read for several reasons. First, it presents the problem clearly (e.g. the introduction provides a clear and concise presentation of the issue and past work) and its crystal-clear writing facilitates the reader's understanding of theoretical approaches and results. Second, the analysis is competently done and adds to previous work by showing that very general conditions are expected to be favourable to the spread of the type of inversion considered here. And third, it provides food for thought about the role of inversions in the origin or the reinforcement of divergence between nascent species. One result of this work is that an inversion linked to pre-zygotic isolation "is favoured so long as there is viability selection against recombinant genotypes", suggesting that genetic incompatibilities must have evolved first and that inversions capturing mating preference loci may then enhance pre-existing reproductive isolation. However, the results also show that inversions are more likely to be favoured in hybridizing populations among which gene flow is still high, rather than in more strongly isolated populations. This matches the observation that inversions are more frequently observed between sympatric species than between allopatric ones. References [1] Trickett AJ, Butlin RK. 1994. Recombination Suppressors and the Evolution of New Species. Heredity 73:339-345. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1994.180 [2] Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M. 2016. Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions. Evolution 70: 1465–1472. doi: 10.1111/evo.12954 | Prezygotic isolation, mating preferences, and the evolution of chromosomal inversions | Dagilis AJ, Kirkpatrick M | Chromosomal inversions are frequently implicated in isolating species. Models have shown how inversions can evolve in the context of postmating isolation. Inversions are also frequently associated with mating preferences, a topic that has not been... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Denis Roze | 2016-12-13 22:11:54 | View | |

28 Feb 2023

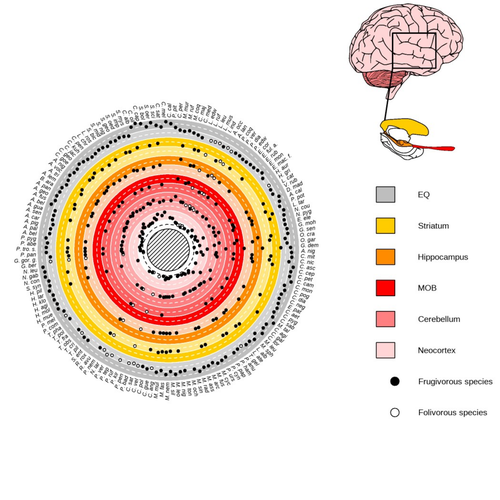

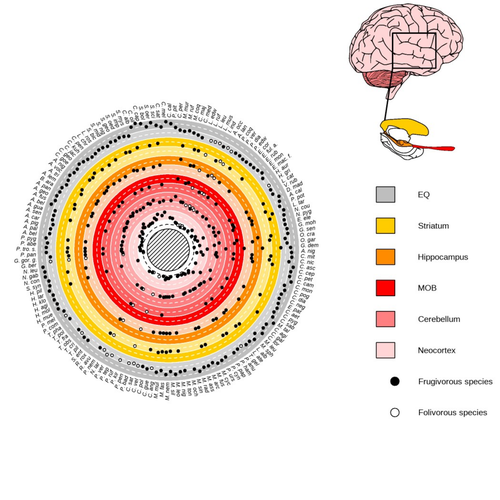

Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architectureBenjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912Macroevolutionary drivers of brain evolution in primatesRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Paula Gonzalez, Orlin Todorov and 3 anonymous reviewersStudying the evolution of animal cognition is challenging because many environmental and species-related factors can be intertwined, which is further complicated when looking at deep-time evolution. Previous knowledge has emphasized the role of intraspecific interactions in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. However, much less is known about such an effect at the interspecific level. Yet, the coexistence of different species in the same geographic area at a given time (sympatry) can impact the evolutionary history of species through character displacement due to biotic interactions. Trait evolution has been observed and tested with morphological external traits but more rarely with brain evolution. Compared to most species’ traits, brain evolution is even more delicate to assess since specific brain regions can be involved in different functions, may they be individual-based and social-based information processing. In a very original and thoroughly executed study, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) addressed the question: How does the co-occurrence of congeneric species shape brain evolution and influence species diversification? By considering brain size as a proxy for cognition, they evaluated whether species sympatry impacted the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates. Fruit resources are hard to find, not continuous through time, heterogeneously distributed across space, but can be predictable. Hence, cognition considerably shapes the foraging strategy and competition for food access can be fierce. Over long timescales, it remains unclear whether brain size and the pace of species diversification are linked in the context of sympatry, and if so how. Recent studies have found that larger brain sizes can be associated with higher diversification rates in birds (Sayol et al. 2019). Similarly, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) thus wondered if the evolution of brain size in primates impacted their dynamic of species diversification, which has been suggested (Melchionna et al. 2020) but not tested. Prior to anything, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) had to retrace the evolutionary history of sympatry between frugivorous primate lineages through time using the primate tree of life, species’ extant distribution, and process-based models to estimate ancestral range evolution. To infer the effect of species sympatry on the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates, the authors evaluated the support for phylogenetic models of brain size evolution accounting or not for species sympatry and investigated the directionality of the selection induced by sympatry on brain size evolution. Finally, to better understand the impact of cognition and interactions between primates on their evolutionary success, they tested for correlations between brain size or species’ sympatry and species diversification. Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) found that the evolution of the whole brain or brain regions used in immediate information processing was best fitted with models not considering sympatry. By contrast, models considering species sympatry best predicted the evolution of brain regions related to long-term memory of interactions with the socio-ecological environment, with a decrease in their size along with stronger sympatry. Specifically, they found that sympatry was associated with a decrease in the relative size of the hippocampus and striatum, but had no significant effect on the neocortex, cerebellum, or overall brain size. The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a crucial role in processing and memorizing spatiotemporal information, which is relevant for frugivorous primates in their foraging behavior. The study suggests that competition between sympatric species for limited food resources may lead to a more complex and unpredictable food distribution, which may in turn render cognitive foraging not advantageous and result in a selection for smaller brain regions involved in foraging. Niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry may also impact cognitive abilities, with more specialized diets requiring lower cognitive abilities and smaller brain region sizes. On the other hand, the absence of an effect of sympatry on brain regions involved in immediate sensory information processing, such as the cerebellum and neocortex, suggests that foragers do not exploit cues left out by sympatric heterospecific species, or they may discard environmental cues in favor of social cues. This is a remarkable study that highlights the importance of considering the impact of ecological factors, such as sympatry, on the evolution of specific brain regions involved in cognitive processes, and the potential trade-offs in brain region size due to niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms behind these effects and to test for the possible role of social cues in the evolution of brain regions. This study provides insights into the selective pressures that shape brain evolution in primates. References Melchionna M, Mondanaro A, Serio C, Castiglione S, Di Febbraro M, Rook L, Diniz-Filho JAF, Manzi G, Profico A, Sansalone G, Raia P (2020) Macroevolutionary trends of brain mass in Primates. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz161 Robira B, Perez-Lamarque B (2023) Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture. bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.490912, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912 Sayol F, Lapiedra O, Ducatez S, Sol D (2019) Larger brains spur species diversification in birds. Evolution, 73, 2085–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13811 | Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture | Benjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque | <p style="text-align: justify;">The main hypotheses on the evolution of animal cognition emphasise the role of conspecifics in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. Yet, space is often simultaneously occupied by multiple sp... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2022-05-10 13:43:02 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shiftsGilles Didier https://doi.org/10.1101/376756Fitting diversification models on undated or partially dated treesRecommended by Nicolas Lartillot based on reviews by Amaury Lambert, Dominik Schrempf and 1 anonymous reviewerPhylogenetic trees can be used to extract information about the process of diversification that has generated them. The most common approach to conduct this inference is to rely on a likelihood, defined here as the probability of generating a dated tree T given a diversification model (e.g. a birth-death model), and then use standard maximum likelihood. This idea has been explored extensively in the context of the so-called diversification studies, with many variants for the models and for the questions being asked (diversification rates shifting at certain time points or in the ancestors of particular subclades, trait-dependent diversification rates, etc). References [1] Didier, G. (2020) Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts. bioRxiv, 376756, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/376756 | Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts | Gilles Didier | <p>Dating the tree of life is a task far more complicated than only determining the evolutionary relationships between species. It is therefore of interest to develop approaches apt to deal with undated phylogenetic trees. The main result of this ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Macroevolution | Nicolas Lartillot | 2019-01-30 11:28:58 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer