Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Nov 2022

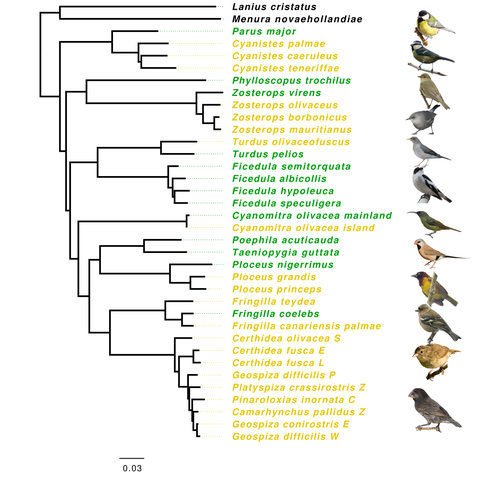

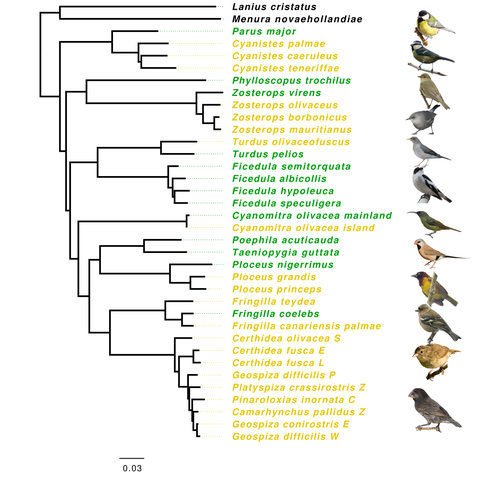

Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndromeMathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450Demographic effects may affect adaptation to islandsRecommended by Emma Berdan based on reviews by Steven Fiddaman and 3 anonymous reviewersThe unique challenges associated with living on an island often result in organisms displaying a specific suite of traits commonly referred to as “island syndrome” (Adler and Levins, 1994; Burns, 2019; Baeckens and Van Damme, 2020). Large phenotypic shifts such as changes in size (e.g. shifts to gigantism or dwarfism, Lomolino, 2005) or coloration (Doutrelant et al., 2016) abound in the literature. However, less obvious phenotypes may also play a key role in adaptation to islands. One such trait, reduced immune function, has important implications for the future of island populations in the face of anthropogenic-induced changes. Due to lower parasite pressure caused by a less diverse and less virulent parasite population, island hosts may show a decrease in immune defenses (Beadell et al., 2006; Pérez‐Rodríguez et al., 2013). However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as many studies have found ambiguous or conflicting results (Matson, 2006; Illera et al., 2015). While most previous work has examined various immunological parameters (e.g., antibody concentrations), here, Barthe et al. (2022) take the novel approach of examining molecular signatures of immune genes. Using comparative genomic data from 34 different species of birds the authors examine the ratio of synonymous substitutions (i.e., not changing an amino acid) to non-synonymous substitutions (i.e., changing an amino acid) in innate and acquired immune genes (Pn/Ps ratio). Because population sizes on islands are lower which will affect molecular evolution, they compare these results to data from 97 control genes. Assuming relaxed selection on islands predicts that the difference between the Pn/Ps ratio of immune genes and of control genes (ΔPn/Ps) is greater in island species compared to mainland ones. As with previous work the authors found that the results differ depending on the category of immune genes. Both forms of innate defense: beta-defensins and Toll-like receptors did not show higher ΔPn/Ps for island populations. As these genes still have a higher Pn/Ps than control genes, the authors argue these results are in line with these genes being under purifying selection but lacking an “island effect”. Instead, the authors argue that demographic effects (i.e., reductions in Ne) may lead to the decreased immunity documented in other studies. In contrast, there was a reduction in Pn/Ps in MHC II genes, known to be under balancing selection. This reduction was stronger in island species and thus the authors argue that this is the only class of genes where a role for relaxed selection can be invoked. Together these results demonstrate that the changes in immunity experienced by island species are complex and that different categories of immune genes can experience different selective pressures. By including control genes in their study, they particularly highlight the importance of accounting for shifts in Ne when examining patterns of island species evolution. Hopefully, this kind of framework will be applied to other taxa to determine if these results are widespread or more specific to birds. References Adler GH, Levins R (1994) The Island Syndrome in Rodent Populations. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1086/418744 Baeckens S, Van Damme R (2020) The island syndrome. Current Biology, 30, R338–R339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029 Barthe M, Doutrelant C, Covas R, Melo M, Illera JC, Tilak M-K, Colombier C, Leroy T, Loiseau C, Nabholz B (2022) Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome. bioRxiv, 2021.11.21.469450, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450 Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Graves GR, Jhala YV, Peirce MA, Rahmani AR, Fonseca DM, Fleischer RC (2006) Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2935–2944. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3671 Burns KC (2019) Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379953 Doutrelant C, Paquet M, Renoult JP, Grégoire A, Crochet P-A, Covas R (2016) Worldwide patterns of bird colouration on islands. Ecology Letters, 19, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12588 Illera JC, Fernández-Álvarez Á, Hernández-Flores CN, Foronda P (2015) Unforeseen biogeographical patterns in a multiple parasite system in Macaronesia. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1858–1870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12548 Lomolino MV (2005) Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01314.x Matson KD (2006) Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 Pérez-Rodríguez A, Ramírez Á, Richardson DS, Pérez-Tris J (2013) Evolution of parasite island syndromes without long-term host population isolation: parasite dynamics in Macaronesian blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 22, 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12084 | Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome | Mathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Shared ecological conditions encountered by species that colonize islands often lead to the evolution of convergent phenotypes, commonly referred to as “island syndrome”. Reduced immune functions have been previousl... |  | Adaptation, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emma Berdan | 2021-11-28 11:01:31 | View | |

14 Mar 2017

POSTPRINT

Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiMarianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055A valuable work lying at the crossroad of neuro-ethology, evolution and ecology in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukiiRecommended by Arnaud Estoup and Ruth Arabelle HufbauerAdaptations to a new ecological niche allow species to access new resources and circumvent competitors and are hence obvious pathways of evolutionary success. The evolution of agricultural pest species represents an important case to study how a species adapts, on various timescales, to a novel ecological niche. Among the numerous insects that are agricultural pests, the ability to lay eggs (or oviposit) in ripe fruit appears to be a recurrent scenario. Fruit flies (family Tephritidae) employ this strategy, and include amongst their members some of the most destructive pests (e.g., the olive fruit fly Bactrocera olea or the medfly Ceratitis capitata). In their ms, Karageorgi et al. [1] studied how Drosophila suzukii, a new major agricultural pest species that recently invaded Europe and North America, evolved the novel behavior of laying eggs into undamaged fresh fruit. The close relatives of D. suzukii lay their eggs on decaying plant substrates, and thus this represents a marked change in host use that links to substantial economic losses to the fruit industry. Although a handful of studies have identified genetic changes causing new behaviors in various species, the question of the evolution of behavior remains a largely uncharted territory. The study by Karageorgi et al. [1] represents an original and most welcome contribution in this domain for a non-model species. Using clever behavioral experiments to compare D. suzukii to several related Drosophila species, and complementing those results with neurogenetics and mutant analyses using D. suzukii, the authors nicely dissect the sensory changes at the origin of the new egg-laying behavior. The experiments they describe are easy to follow, richly illustrate through figures and images, and particularly well designed to progressively decipher the sensory bases driving oviposition of D. suzukii on ripe fruit. Altogether, Karageorgi et al.’s [1] results show that the egg-laying substrate preference of D. suzukii has considerably evolved in concert with its morphology (especially its enlarged, serrated ovipositor that enables females to pierce the skin of many ripe fruits). Their observations clearly support the view that the evolution of traits that make D. suzukii an agricultural pest included the modification of several sensory systems (i.e. mechanosensation, gustation and olfaction). These differences between D. suzukii and its close relatives collectively underlie a radical change in oviposition behavior, and were presumably instrumental in the expansion of the ecological niche of the species. The authors tentatively propose a multi-step evolutionary scenario from their results with the emergence of D. suzukii as a pest species as final outcome. Such formalization represents an interesting evolutionary model-framework that obviously would rely upon further data and experiments to confirm and refine some of the evolutionary steps proposed, especially the final and recent transition of D. suzukii from non-invasive to invasive species. References [1] Karageorgi M, Bräcker LB, Lebreton S, Minervino C, Cavey M, Siju KP, Grunwald Kadow IC, Gompel N, Prud’homme B. 2017. Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii. Current Biology, 27: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.055 | Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest Drosophila suzukii | Marianthi Karageorgi, Lasse B. Bräcker, Sébastien Lebreton, Caroline Minervino, Matthieu Cavey, K.P. Siju, Ilona C. Grunwald Kadow, Nicolas Gompel, Benjamin Prud’homme | The rise of a pest species represents a unique opportunity to address how species evolve new behaviors and adapt to novel ecological niches. We address this question by studying the egg-laying behavior of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive agricultur... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution | Arnaud Estoup | 2017-03-13 17:42:00 | View | |

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS 10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in pollinat... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

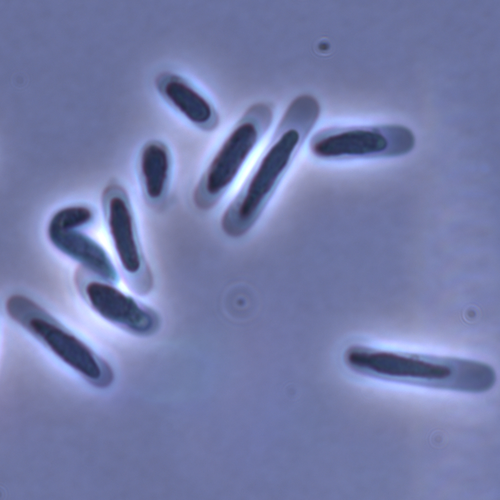

06 Oct 2022

Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch.Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic contextRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia. Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009). This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value. References Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15 Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414 Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5 Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108 Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536 | Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View | |

27 Jul 2020

Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebratesJuan C. Opazo, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Scott V. Edwards https://doi.org/10.1101/794404An evolutionary view of a biomedically important gene familyRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis manuscript [1] investigates the evolutionary history of the DAN gene family—a group of genes important for embryonic development of limbs, kidneys, and left-right axis speciation. This gene family has also been implicated in a number of diseases, including cancer and nephropathies. DAN genes have been associated with the inhibition of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. Despite this detailed biochemical and functional knowledge and clear importance for development and disease, evolution of this gene family has remained understudied. The diversification of this gene family was investigated in all major groups of vertebrates. The monophyly of the gene members belonging to this gene family was confirmed. A total of five clades were delineated, and two novel lineages were discovered. The first lineage was only retained in cephalochordates (amphioxus), whereas the second one (GREM3) was retained by cartilaginous fish, holostean fish, and coelanth. Moreover, the patterns of chromosomal synteny in the chromosomal regions harboring DAN genes were investigated. Additionally, the authors reconstructed the ancestral gene repertoires and studied the differential retention/loss of individual gene members across the phylogeny. They concluded that the ancestor of gnathostome vertebrates possessed eight DAN genes that underwent differential retention during the evolutionary history of this group. During radiation of vertebrates, GREM1, GREM2, SOST, SOSTDC1, and NBL1 were retained in all major vertebrate groups. At the same time, GREM3, CER1, and DAND5 were differentially lost in some vertebrate lineages. At least two DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of vertebrates, and at least three DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of chordates. Therefore the patterns of retention and diversification in this gene family appear to be complex. Evolutionary slowdown for the DAN gene family was observed in mammals, suggesting selective constraints. Overall, this article puts the biomedical importance of the DAN family in the evolutionary perspective. References [1] Opazo JC, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Edwards SV (2020) Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 794404, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/794404 | Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates | Juan C. Opazo, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Scott V. Edwards | <p>The DAN gene family (DAN, Differential screening-selected gene Aberrant in Neuroblastoma) is a group of genes that is expressed during development and plays fundamental roles in limb bud formation and digitation, kidney formation and morphogene... |  | Molecular Evolution | Kateryna Makova | 2019-10-15 16:43:13 | View | |

20 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective RegimesHuang Y, Agrawal AF 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336Genetic adaptation counters phenotypic plasticity in experimental evolutionRecommended by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Stephanie BedhommeHow do phenotypic plasticity and adaptive evolution interact in a novel or changing environment? Does evolution by natural selection generally reinforce initially plastic phenotypic responses, or does it instead oppose them? And to what extent does evolution of a trait involve evolution of its plasticity? These questions have lied at the heart of research on phenotypic evolution in heterogeneous environments ever since it was realized that the environment is likely to affect the expression of many (perhaps most) characters of an individual. Importantly, this broad definition of phenotypic plasticity as change in the average phenotype of a given genotype in response to its environment of development (or expression) does not involve any statement about the adaptiveness of the plastic changes. Theory on the evolution of plasticity has devoted much effort to understanding how reaction norm should evolve under different regimes of environmental change in space and time, and depending on genetic constraints on reaction norm shapes. However on an empirically ground, the questions above have mostly been addressed for individual traits, often chosen a priori for their likeliness to exhibit adaptive plasticity, and we still lack more systematic answers. These can be provided by so-called ‘phenomic’ approaches, where a large number of traits are tracked without prior information on their biological or ecological function. A problem is that the number of phenotypic characters that can be measured in an organism is virtually infinite (and to some extent arbitrary), and that scaling issues makes it difficult to compare different sets of traits. Gene-expression levels offer a partial solution to this dilemma, as they can be considered as a very large number of traits (one per typed gene) that can be measured easily and uniformly (fold change in the number of reads in RNAseq). As for any traits, expression levels of different genes may be genetically correlated, to an extent that depends on their regulation mechanism: cis-regulatory sequences that only affect expression of neighboring genes are likely to cause independent gene expression, while more systematic modifiers of expression (e.g. trans-regulators such as transcription factors) may cause correlated genetic responses of the expression of many genes. Huang and Agrawal [1] have studied plasticity and evolution of gene expression level in young larvae of populations of Drosophila melanogaster that have evolved for about 130 generations under either a constant environment (salt or cadmium), or an environment that is heterogeneous in time or space (combining salt and cadmium). They report a wealth of results, of which we summarize the most striking here. First, among genes that (i) were initially highly plastic and (ii) evolved significant divergence in expression levels between constant environment treatments, the evolved divergence is predominantly in the opposite direction to the initial plastic response. This suggests that either plasticity was initially maladaptive, or the selective pressure changed during the evolutionary process (see below). This somewhat unexpected result strikingly mirrors that from a study published last year in Nature [2], where the same pattern was found for responses of guppies to the presence of predators. However, Huang and Agrawal [1] went beyond this study by deciphering the underlying mechanisms in several interesting ways. First, they showed that change in gene expression often occurred at genes close to SNPs with differentiated frequencies across treatments (but not at genes with differentiated SNPs in their coding sequences), suggesting that cis-regulatory sequences are involved. This is also suggested by the fact that changes in gene expression are mostly caused by the increased expression of only one allele at polymorphic loci, and is a first step towards investigating the genetic underpinnings of (co)variation in gene expression levels. Another interesting set of findings concerns evolution of plasticity in treatments with variable environments. To compare the gene-expression plasticity that evolved in these treatments to an expectation, the authors considered that the expression levels in populations maintained for a long time under constant salt or cadmium had reached an optimum. The differences between these expression levels were thus assumed to predict the level of plasticity that should evolve in a heterogeneous environment (with both cadmium and salt) under perfect environmental predictability. The authors showed that plasticity did evolve more in the expected direction in heterogeneous than in constant environments, resulting in better adapted final expression levels across environments. Taken collectively, these results provide an unprecedented set of patterns that are greatly informative on how plasticity and evolution interact in constant versus changing environments. But of course, interpretations in terms of adaptive versus maladaptive plasticity are more challenging, as the authors themselves admit. Even though environmentally determined gene expression is the basic mechanism underlying the phenotypic plasticity of most traits, it is extremely difficult to relate to more integrated phenotypes for which we can understand the selection pressures, especially in multicellular organisms. The authors have recently investigated evolutionary change of quantitative traits in these selected lines, so it might be possible to establish links between reaction norms for macroscopic traits to those for gene expression levels. Such an approach would also involve tracking gene expression throughout life, rather than only in young larvae as done here, thus putting phenotypic complexity back in the picture also for expression levels. Another difficulty is that a plastic response that was originally adaptive may be replaced by an opposite evolutionary response in the long run, without having to invoke initially maladaptive plasticity. For instance, the authors mention the possibility that a generic stress response is initially triggered by cadmium, but is eventually unnecessary and costly after evolution of genetic mechanisms for cadmium detoxification (a case of so-called genetic accommodation). In any case, this study by Huang and Agrawal [1], together with the one by Ghalambor et al. last year [2], reports novel and unexpected results, which are likely to stimulate researchers interested in plasticity and evolution in heterogeneous environments for the years to come. References [1] Huang Y, Agrawal AF. 2016. Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes. PLoS Genetics 12:e1006336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336 [2] Ghalambor CK, Hoke KL, Ruell EW, Fischer EK, Reznick DN, Hughes KA. 2015. Non-adaptive plasticity potentiates rapid adaptive evolution of gene expression in nature. Nature 525: 372-375. doi: 10.1038/nature15256 | Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes | Huang Y, Agrawal AF | Little is known of how gene expression and its plasticity evolves as populations adapt to different environmental regimes. Expression is expected to evolve adaptively in all populations but only those populations experiencing environmental heterog... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Expression Studies, Phenotypic Plasticity | Luis-Miguel Chevin | 2016-12-20 09:04:15 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosisDavid Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewersMonnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time. References [1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265 | Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View | |

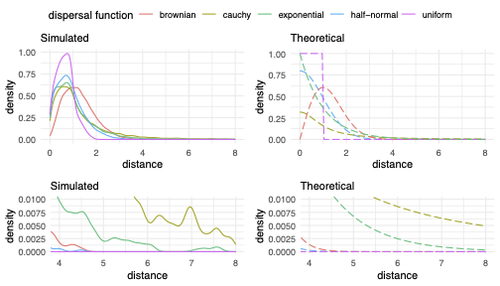

23 Feb 2024

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

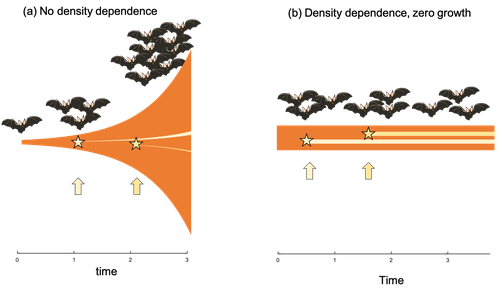

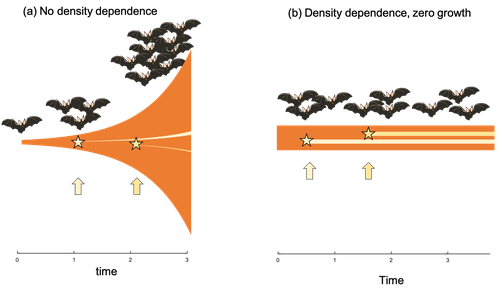

06 Mar 2023

Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexedCharlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060Getting old gracefully, and risk of dying before getting there: a new guide to theory on extrinsic mortality and senescenceRecommended by Sinead English and Shinichi Nakagawa based on reviews by Nicole Walasek and 1 anonymous reviewerWhy is there such variation across species and populations in the rate at which individuals show wear and tear as they get older? Several compelling theoretical explanations have been developed on the conditions under which selection allows for or prevents senescence; a notable one being that proposed by George C Williams in 1957 based on the idea of antagonistic pleiotropy (Williams, 1957). One of the testable predictions of this theory is that, in populations where adults experience higher mortality, senescence is expected to be faster. This is one of the most influential predictions of the paper, being intuitive (when individuals are less likely to survive to later age classes, we expect weakened selection on traits that would avoid senescence in these classes), and fitting with ‘live fast, die young’ life history framing. As such, it has been widely incorporated into how we think about the evolution of senescence and has received considerable support in comparative studies across species and populations. However, it would be misleading to sit back at this point and think we have ‘solved’ the problem of understanding variation in senescence, and how this is linked with mortality. It turns out that the Williams 1957 paper is hotly contested by theoreticians: for the past 30 years – with increasing focus in the last 4 years – a growing body of models and opinion pieces have proposed flaws in the paper itself and in how it has been interpreted (Abrams, 1993; André and Rousset, 2020; Day and Abrams, 2020; Moorad et al., 2019). Central to several of these critiques is that explicit consideration of density dependence (not considered in Williams’ original paper) changes the conditions under which his predictions hold. A new preprint by de Vries, Gallipaud and Kokko brings further clarity to such critiques of the original paper (Vries et al., 2023). Beyond just continuing the tradition of critiquing Williams’ prediction, however, de Vries et al. provide a clear guide that is accessible to non-theoreticians about the issues with William’s prediction, and the way in which density dependence and how it operates can change when we expect senescence to occur. Rather than reiterate their points here, we suggest a close reading of the paper itself, along with an excellent overview of the paper in a recent blog by Daniel Nettle (Nettle, 2022). In brief, the paper starts by synthesizing earlier theoretical and empirical studies on the topic and presenting a very simple model to highlight how – in the absence of density dependence – Williams’ prediction does not hold because of the unregulated population growth, which is necessarily higher when there is low mortality. As a result, for a lineage with low mortality, any fitness advantage of placing offspring into the lineage later (i.e. selection for reduced senescence) is exactly cancelled out by the fact that earlier-produced offspring have higher fitness returns. They then present a more complex framework, which incorporates realistic mortality distributions, trade-offs between survival and reproduction, and use a series of 10 scenarios of density dependence (and whether this acts on survival or fecundity, and also whether it depends on a threshold or stochastic, or exerts continuing pressure on the trait) to explore selection on fitness-associated traits with age depending on extrinsic mortality. This then generates a range of results for when the Williams prediction holds, when there is no link between mortality and senescence, and when there is an ‘anti-Williams’ result – i.e., where senescence is slower when there is a high mortality. As has been shown in earlier studies, density dependence and how it operates matters, and Williams’ prediction holds most when density dependence affects juvenile age classes (in their model, when adults are less likely to produce them – i.e. there is density dependence on fecundity; or when there is less recruitment into the adult population due to, for example, competition among juveniles). So, perhaps we are now at a point where we can lay to rest the debate on the issues specifically with Williams’ original paper, and instead consider more broadly the key factors to measure when predicting patterns of senescence, and what is tangible for empiricists to quantify in their studies. Here, de Vries et al. provide some helpful insights both into the limitations of their approach and what modelling should be done moving forward, and into how we can link existing studies (for example comparing senescence among populations with varying predation pressure) to the theoretical predictions. At the heart of the latter is understanding the mechanism of density-dependent regulation – does it affect survival or fecundity, which age classes are most sensitive, and how do key traits depend on density? – and this is often difficult to measure in field studies. And from all this we can learn that even very intuitive and extensively discussed concepts in biology do not always have as firm theoretical underpinnings as assumed, and – as should not be surprising – biology is complex and rather than one clear pattern being predicted, this can depend on a multitude of factors. REFERENCES Abrams PA (1993) Does increased mortality favor the evolution of more rapid senescence? Evolution, 47, 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01241.x André J-B, Rousset F (2020) Does extrinsic mortality accelerate the pace of life? A bare-bones approach. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41, 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.03.002 Day T, Abrams PA (2020) Density Dependence, Senescence, and Williams’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 300–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.11.005 Moorad J, Promislow D, Silvertown J (2019) Evolutionary Ecology of Senescence and a Reassessment of Williams’ ‘Extrinsic Mortality’ Hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.02.006 Nettle AD (2022) Live fast and die young (maybe). https://www.danielnettle.org.uk/2022/02/18/live-fast-and-die-young-maybe/ (accessed 2.27.23). de Vries C, Galipaud M, Kokko H (2023) Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed. bioRxiv, 2022.01.27.478060, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.27.478060 Williams GC (1957) Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution, 11, 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1957.tb02911.x | Extrinsic mortality and senescence: a guide for the perplexed | Charlotte de Vries, Matthias Galipaud, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">Do environments or species traits that lower the mortality of individuals create selection for delaying senescence? Reading the literature creates an impression that mathematically oriented biologists cannot agree o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Sinead English | 2022-08-26 14:30:16 | View | |

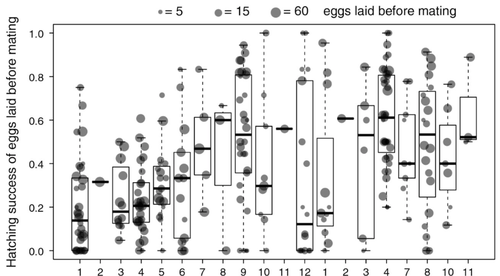

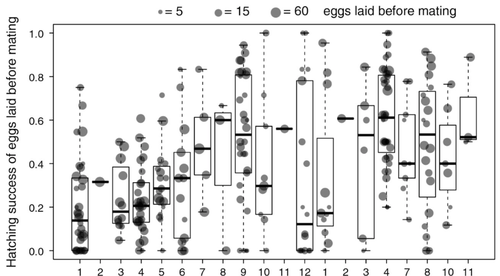

11 Apr 2023

Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects?Chloé Larose, Guillaume Lavanchy, Susana Freitas, Darren J. Parker, Tanja Schwander https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485836Facultative parthenogenesis and transitions from sexual to asexual reproductionRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Despite a vast array of ways in which organisms can reproduce (Bell, 1982), most animals engage in sexual reproduction (Otto & Lenormand, 2002). A fascinating alternative to sex is parthenogenesis, where offspring are produced asexually from a gamete, typically the egg, without receiving genetic material from another gamete (Simon, Delmotte, Rispe, & Crease, 2003). One of the long-standing questions in the field is why parthenogenesis is not more widespread, given the costs associated with sex (Otto & Lenormand, 2002). Natural populations of most species appear to be reproducing either sexually or parthenogenetically, even if a species can employ both reproductive modes (Larose et al 2023). Larose et al (2023) highlight the conundrum in this pattern, as organisms that are capable of employing parthenogenesis facultatively would be able to gain the benefits of both modes of reproduction. Why then, is facultative parthenogenesis not more common? Larose et al (2023) propose that constraints on being efficient in both sexual and asexual reproduction could cause a trade-off between reproductive modes that favours an obligate strategy of either sex or no sex. This would provide an explanation for why facultative parthenogenesis is rare. Timema stick insects provide an excellent system to investigate reproductive strategies, as some species have parthenogenetic females, while other species are sexual, and they show repeated transitions from sexual reproduction to obligate parthenogenesis (Schwander & Crespi, 2009). The authors performed comprehensive and complementary studies in a recently discovered species T. douglasi, in which populations show both modes of reproduction, with some populations consisting only of females and others showing equal proportions of males and females. The sex ratio varied significantly, with the proportion of females ranging between 43-100% across 29 populations. These populations form a monophyletic clade with clustering into three genetic lineages and only a few cases of admixture. Females from all populations were capable of producing unfertilized eggs, but the hatching success varied hugely among populations and lineages (3-100%). Parthenogenetically produced offspring were homozygous, showing that parthenogenesis causes a complete loss of heterozygosity in a single generation. After producing eggs as virgins, females were mated to assess the capacity to also reproduce sexually, and fertilization increased the hatching success of eggs in two lineages. In one lineage, in which the hatching success of unfertilized eggs is similar to that of other sexually reproducing Timema species, fertilization reduced egg-hatching success, indicating a trade-off between reproductive modes with parthenogenetic reproduction performing best. Approximately 58% of the offspring produced after mating were fertilized, demonstrating the capacity of females to reproduce parthenogenetically also after mating has occurred, however with huge variation among individuals. This wonderful and meticulously performed study produces strong and complementary evidence for facultative parthenogenesis in T. douglasi populations. The study shows large variation in how reproductive mode is employed, supporting the existence of a trade-off between sexual and parthenogenetic reproduction. This might be an example of an ongoing transition from sexual to asexual reproduction, which indicates that obligate parthenogenesis may derive via transient facultative parthenogenesis. REFERENCES Bell, G. (1982) The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. University of California Press. 635 p. Otto, S. P., & Lenormand, T. (2002). Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination. Nature Reviews Genetics, 3(4), 252-261. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg761 Schwander, T., & Crespi, B. J. (2009). Multiple direct transitions from sexual reproduction to apomictic parthenogenesis in Timema stick insects. Evolution, 63(1), 84-103. Simon, J.-C., Delmotte, F., Rispe, C., & Crease, T. (2003). Phylogenetic relationships between parthenogens and their sexual relatives: the possible routes to parthenogenesis in animals. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 79(1), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00175.x Larose, C., Lavanchy, G., Freitas, S., Parker, D.J., Schwander, T. (2023) Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects? bioRxiv, 2022.03.25.485836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485836 | Facultative parthenogenesis: a transient state in transitions between sex and obligate asexuality in stick insects? | Chloé Larose, Guillaume Lavanchy, Susana Freitas, Darren J. Parker, Tanja Schwander | <p>Transitions from obligate sex to obligate parthenogenesis have occurred repeatedly across the tree of life. Whether these transitions occur abruptly or via a transient phase of facultative parthenogenesis is rarely known. We discovered and char... |  | Reproduction and Sex | Trine Bilde | 2022-05-20 10:41:13 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer