Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 May 2020

Potential adaptive divergence between subspecies and populations of snapdragon plants inferred from QST – FST comparisonsSara Marin, Anaïs Gibert, Juliette Archambeau, Vincent Bonhomme, Mylène Lascoste and Benoit Pujol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3628168From populations to subspecies… to species? Contrasting patterns of local adaptation in closely-related taxa and their potential contribution to species divergenceRecommended by Emmanuelle Porcher based on reviews by Sophie Karrenberg, Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez and 1 anonymous reviewerElevation gradients are convenient and widely used natural setups to study local adaptation, particularly in these times of rapid climate change [e.g. 1]. Marin and her collaborators [2] did not follow the mainstream, however. Instead of tackling adaptation to climate change, they used elevation gradients to address another crucial evolutionary question [3]: could adaptation to altitude lead to ecological speciation, i.e. reproductive isolation between populations in spite of gene flow? More specifically, they examined how much local adaptation to environmental variation differed among closely-related, recently diverged subspecies. They studied several populations of two subspecies of snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), with adjacent geographical distributions. Using common garden experiments and the classical, but still useful, QST-FST comparison, they demonstrate contrasting patterns of local adaptation to altitude between the two subspecies, with several traits under divergent selection in A. majus striatum but none in A. majus pseudomajus. These differences in local adaptation may contribute to species divergence, and open many stimulating questions on the underlying mechanisms, such as the identity of environmental drivers or contribution of reproductive isolation involving flower color polymorphism. References [1] Anderson, J. T., and Wadgymar, S. M. (2020). Climate change disrupts local adaptation and favours upslope migration. Ecology letters, 23(1), 181-192. doi: 10.1111/ele.13427 | Potential adaptive divergence between subspecies and populations of snapdragon plants inferred from QST – FST comparisons | Sara Marin, Anaïs Gibert, Juliette Archambeau, Vincent Bonhomme, Mylène Lascoste and Benoit Pujol | <p>Phenotypic divergence among natural populations can be explained by natural selection or by neutral processes such as drift. Many examples in the literature compare putatively neutral (FST) and quantitative genetic (QST) differentiation in mult... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Morphological Evolution, Quantitative Genetics | Emmanuelle Porcher | 2018-08-05 15:34:30 | View | |

20 Nov 2023

Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergenceFrançois Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.28.493856Phenotypic stasis despite genetic divergence and differentiation in Caenorhabditis elegans.Recommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões

Explaining long periods of evolutionary stasis, the absence of change in trait means over geological times, despite the existence of abundant genetic variation in most traits has challenged evolutionary theory since Darwin's theory of evolution by gradual modification (Estes & Arnold 2007). Stasis observed in contemporary populations is even more daunting since ample genetic variation is usually coupled with the detection of selection differentials (Kruuk et al. 2002, Morrissey et al. 2010). Moreover, rapid adaptation to environmental changes in contemporary populations, fuelled by standing genetic variation provides evidence that populations can quickly respond to an adaptive challenge. Explanations for evolutionary stasis usually invoke stabilizing selection as a main actor, whereby optimal trait values remain roughly constant over long periods of time despite small-scale environmental fluctuations. Genetic correlation among traits may also play a significant role in constraining evolutionary changes over long timescales (Schluter 1996). Yet, genetic constraints are rarely so strong as to completely annihilate genetic changes, and they may evolve. Patterns of genetic correlations among traits, as captured in estimates of the G-matrix of additive genetic co-variation, are subject to changes over generations under the action of drift, migration, or selection, among other causes (Arnold et al. 2008). Therefore, under the assumption of stabilizing selection on a set of traits, phenotypic stasis and genetic divergence in patterns of trait correlations may both be observed when selection on trait correlations is weak relative to its effect on trait means. Mallard et al. (2023) set out to test whether selection or drift may explain the divergence in genetic correlation among traits in experimental lines of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and whether stabilizing selection may be a driver of phenotypic stasis. To do so, they analyzed the evolution of locomotion behavior traits over 100 generations of lab evolution in a constant and homogeneous environment after 140 generations of domestication from a largely differentiated set of founder populations. The locomotion traits were transition rates between movement states and direction (still, forward or backward movement). They could estimate the traits' broad-sense G-matrix in three populations at two generations (50 and 100), and in the ancestral mixed population. Similarly, they estimated the shape of the selection surface by regressing locomotion behavior on fertility. Armed with both G-matrix and surface estimates, they could test whether the G's orientation matched selection's orientation and whether changes in G were constrained by selection. They found stasis in trait mean over 100 generations but divergence in the amount and orientation of the genetic variation of the traits relative to the ancestral population. The selected populations changed orientation of their G-matrices and lost genetic variation during the experiment in agreement with a model of genetic drift on quantitative traits. Their estimates of selection also point to mostly stabilizing selection on trait combinations with weak evidence of disruptive selection, suggesting a saddle-shaped selection surface. The evolutionary responses of the experimental populations were mostly consistent with small differentiation in the shape of G-matrices during the 100 generations of stabilizing selection. Mallard et al. (2023) conclude that phenotypic stasis was maintained by stabilizing selection and drift in their experiment. They argue that their findings are consistent with a "table-top mountain" model of stabilizing selection, whereby the population is allowed some wiggle room around the trait optimum, leaving space for random fluctuations of trait variation, and especially trait co-variation. The model is an interesting solution that might explain how stasis can be maintained over contemporary times while allowing for random differentiation of trait genetic co-variation. Whether such differentiation can then lead to future evolutionary divergence once replicated populations adapt to a new environment is an interesting idea to follow. References Arnold, S. J., Bürger, R., Hohenlohe, P. A., Ajie, B. C. and Jones, A. G. 2008. Understanding the evolution and stability of the G-matrix. Evolution 62(10): 2451-2461. | Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergence | François Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether or not genetic divergence in the short-term of tens to hundreds of generations is compatible with phenotypic stasis remains a relatively unexplored problem. We evolved predominantly outcrossing, genetically ... | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Experimental Evolution, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | 2022-09-01 14:32:53 | View | ||

28 Mar 2024

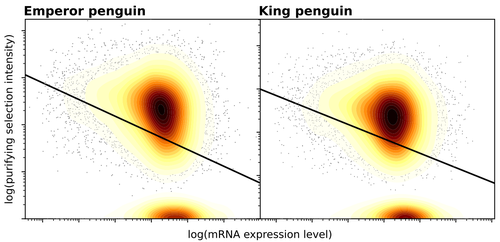

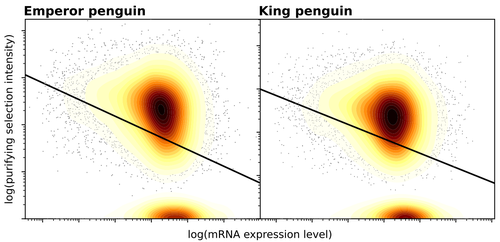

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewerGiven the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View | |

02 Feb 2024

Community structure of heritable viruses in a Drosophila-parasitoids complexJulien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.29.551099The virome of a Drosophilidae-parasitoid communityRecommended by Ben Longdon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

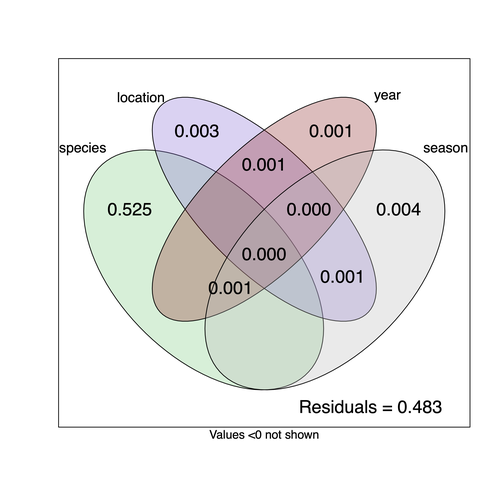

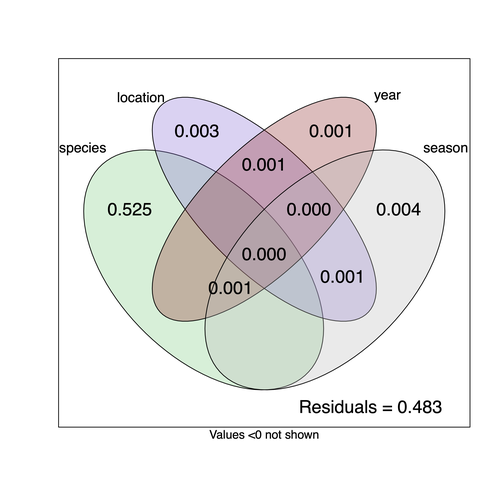

Understanding the factors that shape the virome of a host is key to understanding virus ecology and evolution (Obbard, 2018; French & Holmes, 2020). There is still much to learn about the diversity and distribution of viruses in a host community (Wille et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023). The viruses of parasitoid wasps are well studied, and their viruses, or integrated viral genes, are known to suppress their insect host’s immune response to enhance parasitoid survival (Herniou et al., 2013; Coffman et al., 2022). Likewise, the insect virome is being increasingly well studied (Shi et al., 2016), with the virome of Drosophila species being particularly well characterised over the best part of the last century (L'Heritier & Teissier, 1937; L'Heritier, 1970; Brun & Plus, 1980; Longdon et al., 2010; Longdon et al., 2011; Longdon et al., 2012; Webster et al., 2015; Webster et al., 2016; Medd et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2021). However, the viromes of parasitoids and their insect host communities have been less well studied (Leigh et al., 2018; Caldas-Garcia et al., 2023), and the inherent connectivity between parasitoids and their hosts provides an interesting system to study virus host range and cross-species transmission. Here, Varaldi et al (Varaldi et al., 2024) have examined the viruses associated with a community of nine Drosophilidae hosts and six parasitoids. Using both RNA and DNA sequencing of insects reared for two generations, they selected viruses that are maintained in the lab either via vertical transmission or contamination of rearing medium. From 55 pools of insects they found 53 virus-like sequences, 37 of which were novel. Parasitoids were host to nearly twice as many viruses as their Drosophila hosts, although they note this could be due to differences in the rearing temperatures of the hosts. They next quantified if species, year, season, or location played a role in structuring the virome, finding only a significant effect of host species, which explained just over 50% of the variation in virus distribution. No evidence was found of related species sharing more similar virus communities. Although looking at a limited number of species, this suggests that these viruses are not co-speciating or preferentially host switching between closely related species. Finally, they carried out crosses between lines of the parasitoid Leptopilina heterotoma that were infected and uninfected for a novel Iflavirus found in their sequencing data. They found evidence of high levels of maternal transmission and lower level horizontal transmission between wasp larvae parasitising the same host. No evidence of changes in parasitoid-induced mortality, developmental success or the sex ratio was found in iflavirus-infected parasitoids. Interestingly individuals infected with this RNA virus also contained viral DNA, but this did not appear to be integrated into the wasp genome. Overall, this work has taken the first steps in examining the community structure of the virome of parasitoids together with their Drosophilidae hosts. This work will not doubt stimulate follow-up studies to explore the evolution and ecology of these novel virus communities. References Brun G, Plus N (1980) The viruses of Drosophila. In: The genetics and biology of Drosophila eds Ashburner M & Wright TRF), pp. 625-702. Academic Press, New York. | Community structure of heritable viruses in a *Drosophila*-parasitoids complex | Julien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity and phenotypic impacts related to the presence of heritable bacteria in insects have been extensively studied in the last decades. On the contrary, heritable viruses have been overlooked for several re... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Ben Longdon | 2023-08-03 01:07:43 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

16 Nov 2018

Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen IslandsChristelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil https://doi.org/10.1101/239244Introgression from related species reveals fine-scale structure in an isolated population of mussels and causes patterns of genetic-environment associationsRecommended by Marianne Elias based on reviews by Thomas Broquet and Tatiana GiraudAssessing population connectivity is central to understanding population dynamics, and is therefore of great importance in evolutionary biology and conservation biology. In the marine realm, the apparent absence of physical barriers, large population sizes and high dispersal capacities of most organisms often result in no detectable structure, thereby hindering inferences of population connectivity. In a review paper, Gagnaire et al. [1] propose several ideas to improve detection of population connectivity. Notably, using simulations they show that under certain circumstances introgression from one species into another may reveal cryptic population structure within that second species. References [1] Gagnaire, P.-A., Broquet, T., Aurelle, D., Viard, F., Souissi, A., Bonhomme, F., Arnaud-Haond, S., & Bierne, N. (2015). Using neutral, selected, and hitchhiker loci to assess connectivity of marine populations in the genomic era. Evolutionary Applications, 8, 769–786. doi: 10.1111/eva.12288 | Fine-grained habitat-associated genetic connectivity in an admixed population of mussels in the small isolated Kerguelen Islands | Christelle Fraïsse, Anne Haguenauer, Karin Gerard, Alexandra Anh-Thu Weber, Nicolas Bierne, Anne Chenuil | <p>Reticulated evolution -i.e. secondary introgression / admixture between sister taxa- is increasingly recognized as playing a key role in structuring infra-specific genetic variation and revealing cryptic genetic connectivity patterns. When admi... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Marianne Elias | 2017-12-28 14:16:16 | View | |

04 Jun 2019

Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North AmericaJean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/550319Temperature variance, rather than mean, drives adaptation to local climateRecommended by Fabien Aubret based on reviews by Ben Phillips and Eric GangloffClimate change is impacting eco-systems worldwide and driving many populations to move, adapt or go extinct. It is increasingly appreciated, for example, that species may adjust their phenology in response to climate change, although empirical data is scarce. In this preprint [1], Tourneur and Meunier report an impressive sampling effort in which life-history traits were measured across introduced populations of earwig in North America. The authors examine whether variation in life-history across populations is correlated with aspects of the thermal climate experienced by each population: mean temperature and seasonality of temperature. They find some fascinating correlations between life-history and thermal climate; correlations with the seasonality of temperature, but not with mean temperature. This study provides relatively uncommon data, in the sense that where most of the literature looking at adaptation in animals in response to climate change has focused on physiological traits [2, 3], this study examines changes in life-history traits with time scales relevant to impending climate change, and provides a reasonable argument that this is adaptation, not just constraint. References [1] Tourneur, J.-C. and Meunier, J. (2019). Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America. BioRxiv, 550319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/550319 | Thermal regimes, but not mean temperatures, drive patterns of rapid climate adaptation at a continent-scale: evidence from the introduced European earwig across North America | Jean-Claude Tourneur, Joël Meunier | <p>The recent development of human societies has led to major, rapid and often inexorable changes in the environment of most animal species. Over the last decades, a growing number of studies formulated predictions on the modalities of animal adap... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Fabien Aubret | 2019-02-15 09:12:11 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

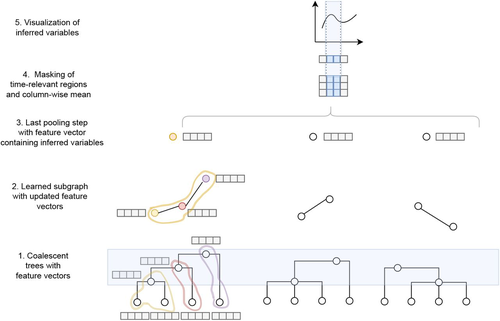

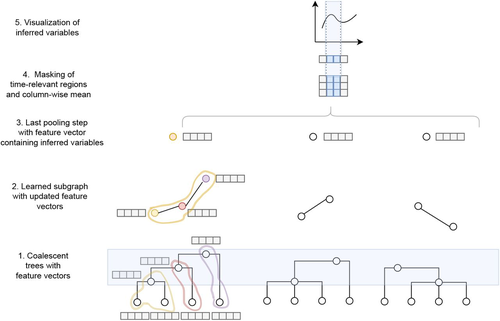

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

30 Jun 2023

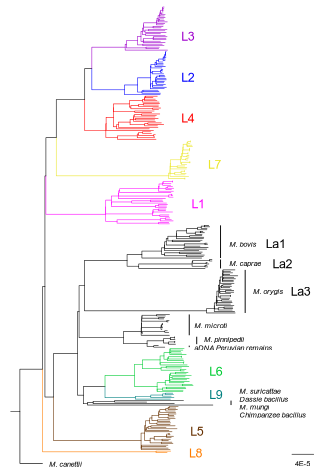

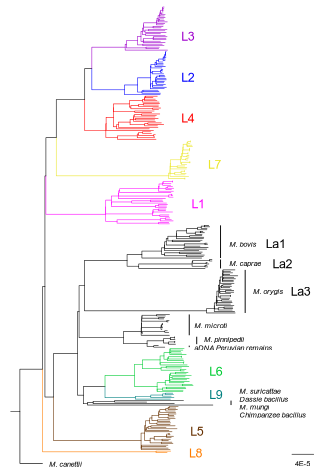

How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonalityChristoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2PHow the tubercle bacillus got its genome: modernising, modelling, and making sense of the stories we tellRecommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this instructive review, Stritt and Gagneux offer a balanced perspective on the evolutionary forces shaping Mycobacterium tuberculosis and make the case that our instinct for storytelling be balanced with quantitative models. M. tuberculosis is perhaps the best-known clonal bacterial pathogen – evolving largely in the absence of horizontal gene transfer. Its genome is full of puzzling patterns, including much higher GC content than most intracellular pathogens (which suggests efficient selection to resist AT-skewed mutational bias) but a very high ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS ~ 0.5, typically interpreted as weak selection against deleterious amino acid changes). The authors offer alternative explanations for these patterns, framing the question: is M. tuberculosis evolution shaped mainly by drift or by efficient selection? They propose that this question can only be answered by accounting for the pathogen’s extreme clonality. A clonal lifestyle can have its advantages, for example when adaptations must arise in a particular order (Kondrashov and Kondrashov 2001). An important disadvantage highlighted by the authors are linkage effects: without recombination to shuffle them up, beneficial mutations are linked to deleterious mutations in the same genome (hitchhiking) and purging deleterious mutations also purges neutral diversity across the genome (background selection). The authors propose the latter – efficient purifying selection and strong linkage – as an explanation for the low genetic diversity observed in M. tuberculosis. This is of course not exclusive of other related explanations, such as clonal interference (Gerrish and Lenski 1998). They also champion the use of forward evolutionary simulations (Haller and Messer 2019) to model the interplay between selection, recombination, and demography as a powerful alternative to traditional backward coalescent models. At times, Stritt and Gagneux are pessimistic about our existing methods – arguing that dN/dS and homoplasies “tell us little about the frequency and strength of selection.” Even though I favour a more optimistic view, I fully agree that our traditional population genetic metrics are sensitive to a slew of different deviations from a standard neutral evolution model and must be interpreted with caution. As I and others have argued, the extent of recombination (measured as the amount of linkage in a genome) is a key factor in determining how best to test for natural selection (Shapiro et al. 2009) and to conduct genotype-phenotype association studies (Chen and Shapiro 2021) in microbes. While this article is focused on the well-studied M. tuberculosis complex, there are many parallels with other clonal bacteria, including pathogens and symbionts. Whatever your favourite bug, we must all be careful to make sure the stories we tell about them are not “just so tales” but are supported, to the extent possible, by data and quantitative models. References Chen, Peter E., and B. Jesse Shapiro. 2021. "Classic Genome-Wide Association Methods Are Unlikely to Identify Causal Variants in Strongly Clonal Microbial Populations." bioRxiv. Stritt, C., Gagneux, S. (2023). How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GW2P | How do monomorphic bacteria evolve? The *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* complex and the awkward population genetics of extreme clonality | Christoph Stritt, Sebastien Gagneux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Exchange of genetic material through sexual reproduction or horizontal gene transfer is ubiquitous in nature. Among the few outliers that rarely recombine and mainly evolve by <em>de novo</em> mutation are a group o... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | B. Jesse Shapiro | Gonçalo Themudo | 2022-12-16 13:41:53 | View |

05 Jan 2023

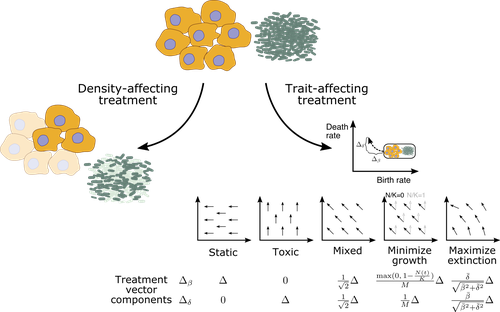

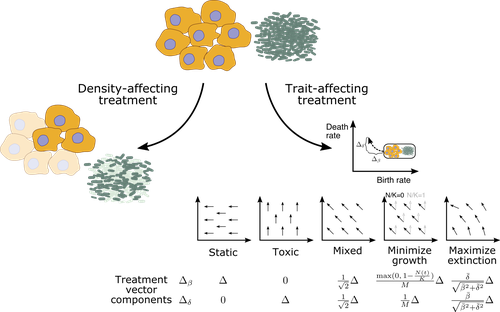

Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populationsMichael Raatz, Arne Traulsen https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570Trait trajectories in evolving populations: insights from mathematical modelsRecommended by Dominik Wodarz based on reviews by Rob Noble and 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of cells within organisms can be an important determinant of disease. This is especially clear in the emergence of tumors and cancers from the underlying healthy tissue. In the healthy state, homeostasis is maintained through complex regulatory processes that ensure a relatively constant population size of cells, which is required for tissue function. Tumor cells escape this homeostasis, resulting in uncontrolled growth and consequent disease. Disease progression is driven by further evolutionary processes within the tumor, and so is the response of tumors to therapies. Therefore, evolutionary biology is an important component required for a better understanding of carcinogenesis and the treatment of cancers. In particular, evolutionary theory helps define the principles of mutant evolution and thus to obtain a clearer picture of the determinants of tumor emergence and therapy responses. The study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] makes an important contribution in this respect. They use mathematical and computational models to investigate trait evolution in the context of evolutionary rescue, motivated by the dynamics of cancer, and also bacterial infections. This study views the establishment of tumors as cell dynamics in harsh environments, where the population is prone to extinction unless mutants emerge that increase evolutionary fitness, allowing them to expand (evolutionary rescue). The core processes of the model include growth, death, and mutations. Random mutations are assumed to give rise to cell lineages with different trait combinations, where the birth and death rates of cells can change. The resulting evolutionary trajectories are investigated in the models, and interesting new results were obtained. For example, the turnover of the population was identified as an important determinant of trait evolution. Turnover is defined as the balance between birth and death, with large rates corresponding to fast turnover and small rates to slow turnover. It was found that for fast cell turnover, a given adaptive step in the trait space results in a smaller increase in survival probability than for cell populations with slower turnover. In other words, evolutionary rescue is more difficult to achieve for fast compared to slow turnover populations. While more mutants can be produced for faster cell turnover rates, the analysis showed that this is not sufficient to overcome the barrier to the evolutionary rescue. This result implies that aggressive tumors with fast cell birth and death rates are less likely to persist and progress than tumors with lower turnover rates. This work emphasizes the importance of measuring the turnover rate in different tumors to advance our understanding of the determinants of tumor initiation and progression. The authors discuss that the well-documented heterogeneity in tumors likely also applies to cellular turnover. If a tumor consists of sub-populations with faster and slower turnover, it is possible that a slower turnover cell clone (e.g. characterized by a degree of dormancy) would enjoy a selective advantage. Another source of heterogeneity in turnover could be given by the hierarchical organization of tumors. Similar to the underlying healthy tissue, many tumors are thought to be maintained by a population of cancer stem cells, while the tumor bulk is made up of more differentiated cells. Tissue stem cells tend to be characterized by a lower turnover than progenitor or transit-amplifying cells. Depending on the assumptions about the self-renewal capacity of these different cell populations, the potential for evolutionary rescue could be different depending on the cell compartment in which the mutant emerges. This might be interesting to explore in the future. There are also implications for treatment. Two types of treatment were investigated: density-affecting treatments in which the density of cells is reduced without altering their trait parameters, and trait-affecting treatments in which the birth and/or death rates are altered. Both types of treatment were found to change the trajectories of trait adaptation, which has potentially important practical implications. Interestingly, it was found that competitive release during treatment can result in situations where after treatment cessation, the non-extinct populations recover to reach sizes that were higher than in the absence of treatment. This points towards the potential of adaptive therapy approaches, where sensitive cells are maintained to some extent to suppress resistant clones [2] competitively. In this context, it is interesting that the success of such approaches might also depend on the turnover of the tumor cell population, as shown by a recent mathematical modeling study [3]. In particular, it was found that adaptive therapy is less likely to work for slow compared to fast turnover tumors. Yet, the current study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] suggests that tumors are more likely to evolve in a slow turnover setting. While there is strong relevance of this analysis for tumor evolution, the results generated in this study have more general relevance. Besides tumors, the paper discusses applications to bacterial disease dynamics in some detail, which is also interesting to compare and contrast to evolutionary processes in cancer. Overall, this study provides insights into the dynamics of evolutionary rescue that represent valuable additions to evolutionary theory. References [1] Raatz M, Traulsen A (2023) Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.496570, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570 [2] Gatenby RA, Silva AS, Gillies RJ, Frieden BR (2009) Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 69, 4894–4903. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3658 [3] Strobl MAR, West J, Viossat Y, Damaghi M, Robertson-Tessi M, Brown JS, Gatenby RA, Maini PK, Anderson ARA (2021) Turnover Modulates the Need for a Cost of Resistance in Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 81, 1135–1147. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0806 | Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations | Michael Raatz, Arne Traulsen | <p style="text-align: justify;">When cancers or bacterial infections establish, small populations of cells have to free themselves from homoeostatic regulations that prevent their expansion. Trait evolution allows these populations to evade this r... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory | Dominik Wodarz | 2022-06-18 08:44:37 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer