Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▼ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

07 Sep 2018

Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineagesFlorentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/161786Genomic parallelism in adaptation to orthogonal environments in sea horsesRecommended by Yaniv Brandvain based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersStudies in speciation genomics have revealed that gene flow is quite common, and that despite this, species can maintain their distinct environmental adaptations. Although researchers are still elucidating the genomic mechanisms by which species maintain their adaptations in the face of gene flow, this often appears to involve few diverged genomic regions in otherwise largely undifferentiated genomes. In this preprint [1], Riquet and colleagues investigate the genetic structuring and patterns of parallel evolution in the long-snouted seahorse. References [1] Riquet, F., Liautard-Haag, C., Woodall, L., Bouza, C., Louisy, P., Hamer, B., Otero-Ferrer, F., Aublanc, P., Béduneau, V., Briard, O., El Ayari, T., Hochscheid, S. Belkhir, K., Arnaud-Haond, S., Gagnaire, P.-A., Bierne, N. (2018). Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages. bioRxiv, 161786, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/161786 | Parallel pattern of differentiation at a genomic island shared between clinal and mosaic hybrid zones in a complex of cryptic seahorse lineages | Florentine Riquet, Cathy Liautard-Haag, Lucy Woodall, Carmen Bouza, Patrick Louisy, Bojan Hamer, Francisco Otero-Ferrer, Philippe Aublanc, Vickie Béduneau, Olivier Briard, Tahani El Ayari, Sandra Hochscheid, Khalid Belkhir, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, Pi... | <p>Diverging semi-isolated lineages either meet in narrow clinal hybrid zones, or have a mosaic distribution associated with environmental variation. Intrinsic reproductive isolation is often emphasized in the former and local adaptation in the la... |  | Hybridization / Introgression, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Yaniv Brandvain | Kathleen Lotterhos, Sarah Fitzpatrick | 2017-07-11 13:12:40 | View |

13 Jan 2019

Why cooperation is not running awayFélix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André https://doi.org/10.1101/316117A nice twist on partner choice theoryRecommended by Erol Akcay based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this paper, Geoffroy et al. [1] deal with partner choice as a mechanism of maintaining cooperation, and argues that rather than being unequivocally a force towards improved payoffs to everyone through cooperation, partner choice can lead to “over-cooperation” where individuals can evolve to invest so much in cooperation that the costs of cooperating partially or fully negate the benefits from it. This happens when partner choice is consequential and effective, i.e., when interactions are long (so each decision to accept or reject a partner is a bigger stake) and when meeting new partners is frequent when unpaired (so that when one leaves an interaction one can find a new partner quickly). Geoffroy et al. [1] show that this tendency to select for overcooperation under such regimes can be counteracted if individuals base their acceptance-rejection of partners not just on the partner cooperativeness, but also on their own. By using tools from matching theory in economics, they show that plastic partner choice generates positive assortment between cooperativeness of the partners, and in the extreme case of perfectly assortative pairings, makes the pair the unit of selection, which selects for maximum total payoff. References [1] Geoffroy, F., Baumard, N., & Andre, J.-B. (2019). Why cooperation is not running away. bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/316117 | Why cooperation is not running away | Félix Geoffroy, Nicolas Baumard, Jean-Baptiste André | <p>A growing number of experimental and theoretical studies show the importance of partner choice as a mechanism to promote the evolution of cooperation, especially in humans. In this paper, we focus on the question of the precise quantitative lev... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Theory | Erol Akcay | 2018-05-15 10:32:51 | View | |

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host speciesFanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417What makes a parasite successful? Parasitoid wasp venoms evolve rapidly in a host-specific mannerRecommended by Élio Sucena based on reviews by Simon Fellous, alexandre leitão and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitoid wasps have developed different mechanisms to increase their parasitic success, usually at the expense of host survival (Fellowes and Godfray, 2000). Eggs of these insects are deposited inside the juvenile stages of their hosts, which in turn deploy several immune response strategies to eliminate or disable them (Yang et al., 2020). Drosophila melanogaster protects itself against parasitoid attacks through the production of specific elongated haemocytes called lamellocytes which form a capsule around the invading parasite (Lavine and Strand, 2002; Rizki and Rizki, 1992) and the subsequent activation of the phenol-oxidase cascade leading to the release of toxic radicals (Nappi et al., 1995). On the parasitoid side, robust responses have evolved to evade host immune defenses as for example the Drosophila-specific endoparasite Leptopilina boulardi, which releases venom during oviposition that modifies host behaviour (Varaldi et al., 2006) and inhibits encapsulation (Gueguen et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012).

References Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Gatti, J.-L., Colinet, D. and Poirié, M. (2021) Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species. bioRxiv, 2020.10.24.353417, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417 Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Kremmer, L., Rebuf, C., Gatti, J.-L., Malausa, T., Colinet, D., Poiré, M. and Léne. (2019). Rapid and Differential Evolution of the Venom Composition of a Parasitoid Wasp Depending on the Host Strain. Toxins, 11(629). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11110629 Colinet, D., Deleury, E., Anselme, C., Cazes, D., Poulain, J., Azema-Dossat, C., Belghazi, M., Gatti, J. L. and Poirié, M. (2013). Extensive inter- and intraspecific venom variation in closely related parasites targeting the same host: The case of Leptopilina parasitoids of Drosophila. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43(7), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.010 Colinet, D., Dubuffet, A., Cazes, D., Moreau, S., Drezen, J. M. and Poirié, M. (2009). A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 33(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013 Fellowes, M. D. E. and Godfray, H. C. J. (2000). The evolutionary ecology of resistance to parasitoids by Drosophila. Heredity, 84(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00685.x Gueguen, G., Rajwani, R., Paddibhatla, I., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2011). VLPs of Leptopilina boulardi share biogenesis and overall stellate morphology with VLPs of the heterotoma clade. Virus Research, 160(1–2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.005 Lavine, M. D. and Strand, M. R. (2002). Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32(10), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9 Martinez, J., Duplouy, A., Woolfit, M., Vavre, F., O’Neill, S. L. and Varaldi, J. (2012). Influence of the virus LbFV and of Wolbachia in a host-parasitoid interaction. PloS One, 7(4), e35081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035081 Nappi, A. J., Vass, E., Frey, F. and Carton, Y. (1995). Superoxide anion generation in Drosophila during melanotic encapsulation of parasites. European Journal of Cell Biology, 68(4), 450–456. Poirié, M., Colinet, D. and Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004 Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 16(2–3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z Schlenke, T. A., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathogens, 3(10), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030158 Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology, 132(Pt 6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009930 Yang, L., Qiu, L., Fang, Q., Stanley, D. W. and Gong‐Yin, Y. (2020). Cellular and humoral immune interactions between Drosophila and its parasitoids. Insect Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12863

| Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species | Fanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié | <p>Female endoparasitoid wasps usually inject venom into hosts to suppress their immune response and ensure offspring development. However, the parasitoid’s ability to evolve towards increased success on a given host simultaneously with the evolut... |  | Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Élio Sucena | 2020-10-26 15:00:55 | View | |

23 Jan 2023

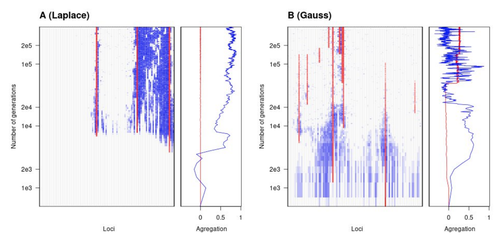

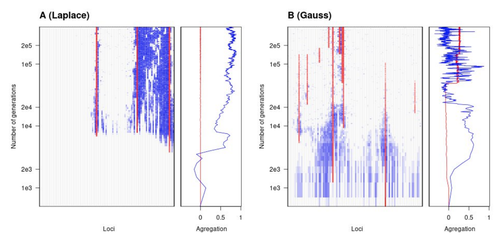

The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a clineFabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280Environmental and fitness landscapes matter for the genetic basis of local adaptationRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Natural landscapes are often composite, with spatial variation in environmental factors being the norm rather than exception. Adaptation to such variation is a major driver of diversity at all levels of biological organization, from genes to phenotypes, species and ultimately ecosystems. While natural selection favours traits that show a better fit to local conditions, the genomic response to such selection is not necessarily straightforward. This is because many quantitative traits are complex and the product of many loci, each with a small to moderate phenotypic contribution. Adapting to environmental challenges that occur in narrow ranges may thus prove difficult as each individual locus is easily swamped by alleles favoured across the rest of the population range. To better understand whether and how evolution overcomes such a hurdle, Laroche and Lenormand [1] combine quantitative genetics and population genetic modelling to track genomic changes that underpin a trait whose fitness optimum differs between a certain spatial range, referred to as a “pocket”, and the rest of the habitat. As it turns out from their analysis, one critical and probably underappreciated factor in determining the type of genetic architecture that evolves is how fitness declines away from phenotypic optima. One classical and popular model of fitness landscape that relates trait value to reproductive success is Gaussian, whereby small trait variations away from the optimum result in even smaller variations in fitness. This facilitates local adaptation via the invasion of alleles of small effects as carriers inside the pocket show a better fit while those outside the pocket only suffer a weak fitness cost. By contrast, when the fitness landscape is more peaked around the optimum, for instance where the decline is linear, adaptation through weak effect alleles is less likely, requiring larger pockets that are less easily swamped by alleles selected in the rest of the range. In addition to mathematically investigating the initial emergence of local adaptation, Laroche and Lenormand use computer simulations to look at its long-term maintenance. In principle, selection should favour a genetic architecture that consolidates the phenotype and increases its heritability, for instance by grouping several alleles of large effects close to one another on a chromosome to avoid being broken down by meiotic recombination. Whether or not this occurs also depends on the fitness landscape. When the landscape is Gaussian, the genetic architecture of the trait eventually consists of tightly linked alleles of large effects. The replacement of small effects by large effects loci is here again promoted by the slow fitness decline around the optimum. This is because any shift in architecture in an adapted population requires initially crossing a fitness valley. With a Gaussian landscape, this valley is shallow enough to be crossed, facilitated by a bit of genetic drift. By contrast, when fitness declines linearly around the optimum, genetic architecture is much less evolutionarily labile as any architecture change initially entails a fitness cost that is too high to bear. Overall, Laroche and Lenormand provide a careful and thought-provoking analysis of a classical problem in population genetics. In addition to questioning some longstanding modelling assumptions, their results may help understand why differentiated populations are sometimes characterized by “genomic islands” of divergence, and sometimes not. References [1] Laroche F, Lenormand T (2022) The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline. bioRxiv, 2022.06.30.498280, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.30.498280 | The genetic architecture of local adaptation in a cline | Fabien Laroche, Thomas Lenormand | <p>Local adaptation is pervasive. It occurs whenever selection favors different phenotypes in different environments, provided that there is genetic variation for the corresponding traits and that the effect of selection is greater than the effect... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Charles Mullon | 2022-07-07 08:46:47 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

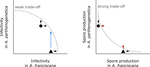

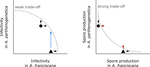

Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasitesEva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/621581Trade-offs in fitness components and ecological source-sink dynamics affect host specialisation in two parasites of Artemia shrimpsRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin

Ecological specialisation, especially among parasites infecting a set of host species, is ubiquitous in nature. Host specialisation can be understood as resulting from trade-offs in parasite infectivity, virulence and growth. However, it is not well understood how variation in these trade-offs shapes the overall fitness trade-off a parasite faces when adapting to multiple hosts. For instance, it is not clear whether a strong trade-off in one fitness component may sufficiently constrain the evolution of a generalist parasite despite weak trade-offs in other components. A second mechanism explaining variation in specialisation among species is habitat availability and quality. Rare habitats or habitats that act as ecological sinks will not allow a species to persist and adapt, preventing a generalist phenotype to evolve. Understanding the prevalence of those mechanisms in natural systems is crucial to understand the emergence and maintenance of host specialisation, and biodiversity in general. References [1] Lievens, E.J.P., Michalakis, Y. and Lenormand, T. (2019). Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites. bioRxiv, 621581, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/621581 | Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites | Eva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand | <p>The evolution of host specialization has been studied intensively, yet it is still often difficult to determine why parasites do not evolve broader niches – in particular when the available hosts are closely related and ecologically similar. He... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Frédéric Guillaume | 2019-05-13 13:44:34 | View | |

26 Sep 2017

Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoiseEtienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/101980A genomic perspective is needed for the re-evaluation of species boundaries, evolutionary trajectories and conservation strategies for the Galápagos giant tortoisesRecommended by Michael C. Fontaine based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersGenome-wide data obtained from even a small number of individuals can provide unprecedented levels of detail about the evolutionary history of populations and species [1], determinants of genetic diversity [2], species boundaries and the process of speciation itself [3]. Loire and Galtier [4] present a clear example, using the emblematic Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra), of how multi-species comparative population genomic approaches can provide valuable insights about population structure and species delimitation even when sample sizes are limited but the number of loci is large and distributed across the genome. Galápagos giant tortoises are endemic to the Galápagos Islands and are currently recognized as an endangered, multi-species complex including both extant and extinct taxa. Taxonomic definitions are based on morphology, geographic isolation and population genetic evidence based on short DNA sequences of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) and/or a dozen or so nuclear microsatellite loci [5-8]. The species complex enjoys maximal protection. Population recoveries have been quite successful and spectacular conservation programs based on mitochondrial genes and microsatellites are ongoing. This includes for example individual translocations, breeding program, “hybrid” sterilization or removal, and resurrection of extinct lineages). In 2013, Loire et al. [9] provided the first population genomic analyses based on genome scale data (~1000 coding loci derived from blood-transcriptomes) from five individuals, encompassing three putative “species”: Chelonnoidis becki, C. porteri and C. vandenburghi. Their results raised doubts about the validity/accuracy of the currently accepted designations of “genetic distinctiveness”. However, the implications for conservation and management have remained unnoticed. In 2017, Loire and Galtier [4] have re-appraised this issue using an original multi-species comparative population genomic analysis of their previous data set [9]. Based on a comparison of 53 animal species, they show that both the level of genome-wide neutral diversity (πS) and level of population structure estimated using the inbreeding coefficient (F) are much lower than would be expected from a sample covering multiple species. The observed values are more comparable to those typically reported at the “among population” level within a single species such as human (Homo sapiens). The authors go to great length to assess the sensitivity of their method to detect population structure (or lack thereof) and show that their results are robust to potential issues, such as contamination and sequencing errors that can occur with Next Generation Sequencing techniques; and biases related to the small sample size and sub-sampling of individuals. They conclude that published mtDNA and microsatellite-based assessment of population structure and species designations may be biased towards over-splitting. This manuscript is a very good read as it shows the potential of the now relatively affordable genome-wide data for helping to both resolve and clarify population and species boundaries, illuminate demographic trends, evolutionary trajectories of isolated groups, patterns of connectivity among them, and test for evidence of local adaptation and even reproductive isolation. The comprehensive information provided by genome-wide data can critically inform and assist the development of the best strategies to preserve endangered populations and species. Loire and Galtier [4] make a strong case for applying genomic data to the Galápagos giant tortoises, which is likely to redirect conservation efforts more effectively and at lower cost. The case of the Galápagos giant tortoises is certainly a very emblematic example, which will find an echo in many other endangered species conservation programs. References [1] Li H and Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475: 493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature10231 [2] Romiguier J, Gayral P, Ballenghien M, Bernard A, Cahais V, Chenuil A, Chiari Y, Dernat R, Duret L, Faivre N, Loire E, Lourenco JM, Nabholz B, Roux C, Tsagkogeorga G, Weber AA-T, Weinert LA, Belkhir K, Bierne N, Glémin S and Galtier N. 2014. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515: 261–263. doi: 10.1038/nature13685 [3] Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N and Bierne N. 2016. Shedding light on the grey zone of speciation along a continuum of genomic divergence. PLoS Biology, 14: e2000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 [4] Loire E and Galtier N. 2017. Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise. bioRxiv 101980, ver. 4 of September 26, 2017. doi: 10.1101/101980 [5] Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Caccone A, Gibbs JP and Powell JR. 2003. Genetic divergence, phylogeography and conservation units of giant tortoises from Santa Cruz and Pinzón, Galápagos Islands. Conservation Genetics, 4: 31–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1021864214375 [6] Ciofi C, Milinkovitch MC, Gibbs JP, Caccone A and Powell JR. 2002. Microsatellite analysis of genetic divergence among populations of giant Galápagos tortoises. Molecular Ecology, 11: 2265–2283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01617.x [7] Garrick RC, Kajdacsi B, Russello MA, Benavides E, Hyseni C, Gibbs JP, Tapia W and Caccone A. 2015. Naturally rare versus newly rare: demographic inferences on two timescales inform conservation of Galápagos giant tortoises. Ecology and Evolution, 5: 676–694. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1388 [8] Poulakakis N, Edwards DL, Chiari Y, Garrick RC, Russello MA, Benavides E, Watkins-Colwell GJ, Glaberman S, Tapia W, Gibbs JP, Cayot LJ and Caccone A. 2015. Description of a new Galápagos giant tortoise species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz island. PLoS ONE, 10: e0138779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138779 [9] Loire E, Chiari Y, Bernard A, Cahais V, Romiguier J, Nabholz B, Lourenço JM and Galtier N. 2013. Population genomics of the endangered giant Galápagos tortoise. Genome Biology, 14: R136. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r136 | Lacking conservation genomics in the giant Galápagos tortoise | Etienne Loire, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Conservation policy in the giant Galápagos tortoise, an iconic endangered animal, has been assisted by genetic markers for ~15 years: a dozen loci have been used to delineate thirteen (sub)species, between which hybridization is prevented. Here... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Michael C. Fontaine | 2017-01-21 15:34:00 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

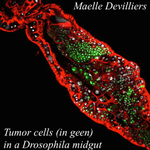

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius eratoErika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.13.523799Impact of pollen-feeding on egg-laying and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in red postman butterfliesRecommended by Adriana Briscoe based on reviews by Carol Boggs, Caroline Mueller and 1 anonymous reviewerGrowth, development and reproduction in animals are all limited by dietary nutrients. Expansion of an organism’s diet to sources not accessible to closely related species reduces food competition, and eases the constraints of nutrient-limited diets. Adult butterflies are herbivorous insects known to feed primarily on nectar from flowers, which is rich in sugars but poor in amino acids. Only certain species in the genus Heliconius are known to also feed on pollen, which is especially rich in amino acids, and is known to prolong their lives by several months. The ability to digest pollen in Heliconius has been linked to specialized feeding behaviors (Krenn et al. 2009) and extra-oral digestion using enzymes, possibly including duplicated copies of cocoonase (Harpel et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2016 and 2018), a protease used by some moths to digest silk upon eclosion from their cocoons. In this reprint, Pinheiro de Castro and colleagues investigated the impact of artificial and natural diets on egg-laying ability, body weight, and cyanogenic glucoside abundance in adult Heliconius erato butterflies of both sexes. Previous studies (Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1981) in H. charithonia demonstrated that access to dietary pollen led to extended egg-laying ability among adult female butterflies compared to females deprived of pollen, and compared to Dryas iulia females which feed only on nectar. In the current study, Pinheiro de Castro et al. (2023) examine the impact of diet on both young and old H. erato, over a longer period of time than the earlier work, highlighting the importance of extending the time period over which effects are evaluated. In addition to extending egg-laying ability in older females, the authors found that pollen in the diet appeared to maintain older female body weight, presumably because the pollen contained nutrients depleted during egg-laying. The authors then investigated the effects of nutrition on the production of cyanogenic glycoside defenses. Heliconius are aposematic butterflies that sequester cyanide-forming defense chemicals from food plants as larvae or synthesize these compounds de novo. The authors found the abundance of cyanogenic glycosides to be significantly greater in butterflies with access to pollen, but again only in older females. Curiously, field studies of male and female H. charithonia butterflies found that females in the wild collected more pollen than males (Mendoza-Cuenca and Macías-Ordóñez 2005). Taken together, these new findings raise the intriguing possibility that females collect more pollen than males, in part, because pollen has a bigger impact on female survival and reproduction. A small limitation of the study is the use of wing length, rather than body weight, at the zero time point. But the trend is clear in both males and females, and it adds supporting detail to the efficacy of pollen feeding as an unusual strategy for increasing fertility and survival in Heliconius butterflies.

References | Pollen-feeding delays reproductive senescence and maintains toxicity of Heliconius erato | Erika C. Pinheiro de Castro, Josie McPherson, Glennis Jullian, Anniina L. K. Mattila, Søren Bak, Stephen Montgomery, Chris Jiggins | <p>Dietary shifts may act to ease energetic constraints and allow organisms to optimise life-history traits. Heliconius butterflies differ from other nectar-feeders due to their unique ability to digest pollen, which provides a reliable source of ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Adriana Briscoe | 2023-02-07 12:59:54 | View | |

08 Aug 2018

Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutationsE. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David https://doi.org//273367Inbreeding compensates for reduced sexual selection in purging deleterious mutationsRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTwo evolutionary processes have been shown in theory to enhance the effects of natural selection in purging deleterious mutations from a population (here ""natural"" selection is defined as ""selection other than sexual selection""). First, inbreeding, especially self-fertilization, facilitates the removal of deleterious recessive alleles, the effects of which are largely hidden from selection in heterozygotes when mating is random. Second, sexual selection can facilitate the removal of deleterious alleles of arbitrary dominance, with little or no demographic cost, provided that deleterious effects are greater in males than in females (""genic capture""). Inbreeding (especially selfing) and sexual selection are often negatively correlated in nature. Empirical tests of the role of sexual selection in purging deleterious mutations have been inconsistent, potentially due to the positive relationship between sexual selection and intersexual genetic conflict. References [1] Noël, E., Fruitet, E., Lelaurin, D., Bonel, N., Segard, A., Sarda, V., Jarne, P., & David P. (2018). Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations. bioRxiv, 273367, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/273367 | Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations | E. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100055). Theory and empirical data showed that two processes can boost selection against deleterious mutations, ... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Baer | Anonymous | 2018-03-01 08:12:37 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer