Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▼ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasitePalmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS 10.1111/jeb.13002The medicinal value of phytochemicals is hindered by pathogen evolution of resistanceRecommended by Alison Duncan and Sara MagalhaesAs plants cannot run from their enemies, natural selection has favoured the evolution of diverse chemical compounds (phytochemicals) to protect them against herbivores and pathogens. This provides an opportunity for plant feeders to exploit these compounds to combat their own enemies. Indeed, it is widely known that herbivores use such compounds as protection against predators [1]. Recently, this reasoning has been extended to pathogens, and elegant studies have shown that some herbivores feed on phytochemical-containing plants reducing both parasite abundance within hosts [2] and their virulence [3]. References [1] Duffey SS. 1980. Sequestration of plant natural products by insects. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 447-477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.002311 [2] Richardson LL et al. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 282: 20142471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 [3] Lefèvre T et al. 2010. Evidence for trans-generational medication in nature. Ecology Letters 13: 1485-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01537.x [4] Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS. 2017. Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 30: 300-312. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13002 [5] Müller CB, Schmid-Hempel P. 1993. Exploitation of cold temperature as defence against parasitoids in bumblebees. Nature 363: 65-67. doi: 10.1038/363065a0 [6] Potts SG et al. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25: 345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 | Evolution of resistance to single and combined floral phytochemicals by a bumble bee parasite | Palmer-Young EC, Sadd BM, Adler LS | Repeated exposure to inhibitory compounds can drive the evolution of resistance, which weakens chemical defence against antagonists. Floral phytochemicals in nectar and pollen have antimicrobial properties that can ameliorate infection in pollinat... |  | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | 2016-12-14 16:47:14 | View | |

26 Oct 2021

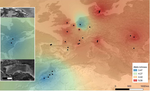

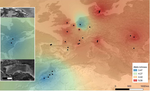

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerEach individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

08 Oct 2019

Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish populationOcéane C. Salles, Glenn R. Almany, Michael L. Berumen, Geoffrey P. Jones, Pablo Saenz-Agudelo, Maya Srinivasan, Simon Thorrold, Benoit Pujol, Serge Planes https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3476529Habitat variation of wild clownfish population shapes selfrecruitment more than genetic effectsRecommended by Philip Munday based on reviews by Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia and Loeske KruukEstimating the genetic and environmental components of variation in reproductive success is crucial to understanding the adaptive potential of populations to environmental change. To date, the heritability of lifetime reproductive success (fitness) has been estimated in a handful of wild animal population, mostly in mammals and birds, but has never been estimated for a marine species. The primary reason that such estimates are lacking in marine species is that most marine organisms have a dispersive larval phase, making it extraordinarily difficult to track the fate of offspring from one generation to the next. References [1] Salles, O. C., Almany, G. R., Berumen, M.L., Jones, G. P., Saenz-Agudelo, P., Srinivasan, M., Thorrold, S. R., Pujol, B., Planes, S. (2019). Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish population. Zenodo, 3476529, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3476529 | Strong habitat and weak genetic effects shape the lifetime reproductive success in a wild clownfish population | Océane C. Salles, Glenn R. Almany, Michael L. Berumen, Geoffrey P. Jones, Pablo Saenz-Agudelo, Maya Srinivasan, Simon Thorrold, Benoit Pujol, Serge Planes | <p>Lifetime reproductive success (LRS), the number of offspring an individual contributes to the next generation, is of fundamental importance in ecology and evolutionary biology. LRS may be influenced by environmental, maternal and additive genet... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Quantitative Genetics | Philip Munday | 2018-10-01 09:00:53 | View | |

03 Aug 2017

POSTPRINT

Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradientsNoémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand 10.1111/evo.13111What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger: can Fisher’s Geometric model predict antibiotic resistance evolution?Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia BankThe increasing number of reported cases of antibiotic resistance is one of today’s major public health concerns. Dealing with this threat involves understanding what drives the evolution of antibiotic resistance and investigating whether we can predict (and subsequently avoid or circumvent) it [1]. References [1] Palmer AC, and Kishony R. 2013. Understanding, predicting and manipulating the genotypic evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nature Review Genetics 14: 243—248. doi: 10.1038/nrg3351 [2] Tenaillon O. 2014. The utility of Fisher’s geometric model in evolutionary genetics. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 45: 179—201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091846 [3] Blanquart F and Bataillon T. 2016. Epistasis and the structure of fitness landscapes: are experimental fitness landscapes compatible with Fisher’s geometric model? Genetics 203: 847—862. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.182691 [4] Harmand N, Gallet R, Jabbour-Zahab R, Martin G and Lenormand T. 2017. Fisher’s geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients. Evolution 71: 23—37. doi: 10.1111/evo.13111 [5] de Visser, JAGM, and Krug J. 2014. Empirical fitness landscapes and the predictability of evolution. Nature 15: 480—490. doi: 10.1038/nrg3744 [6] Palmer AC, Toprak E, Baym M, Kim S, Veres A, Bershtein S and Kishony R. 2015. Delayed commitment to evolutionary fate in antibiotic resistance fitness landscapes. Nature Communications 6: 1—8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8385 | Fisher's geometrical model and the mutational patterns of antibiotic resistance across dose gradients | Noémie Harmand, Romain Gallet, Roula Jabbour-Zahab, Guillaume Martin, Thomas Lenormand | Fisher's geometrical model (FGM) has been widely used to depict the fitness effects of mutations. It is a general model with few underlying assumptions that gives a large and comprehensive view of adaptive processes. It is thus attractive in sever... |  | Adaptation | Inês Fragata | 2017-08-01 16:06:02 | View | |

20 May 2020

How much does Ne vary among species?Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle https://doi.org/10.1101/861849Further questions on the meaning of effective population sizeRecommended by Martin Lascoux based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIn spite of its name, the effective population size, Ne, has a complex and often distant relationship to census population size, as we usually understand it. In truth, it is primarily an abstract concept aimed at measuring the amount of genetic drift occurring in a population at any given time. The standard way to model random genetic drift in population genetics is the Wright-Fisher model and, with a few exceptions, definitions of the effective population size stems from it: “a certain model has effective population size, Ne, if some characteristic of the model has the same value as the corresponding characteristic for the simple Wright-Fisher model whose actual size is Ne” (Ewens 2004). Since Sewall Wright introduced the concept of effective population size in 1931 (Wright 1931), it has flourished and there are today numerous definitions of it depending on the process being examined (genetic diversity, loss of alleles, efficacy of selection) and the characteristic of the model that is considered. These different definitions of the effective population size were generally introduced to address specific aspects of the evolutionary process. One aspect that has been hotly debated since the first estimates of genetic diversity in natural populations were published is the so-called Lewontin’s paradox (1974). Lewontin noted that the observed variation in heterozygosity across species was much smaller than one would expect from the neutral expectations calculated with the actual size of the species. References Brandvain Y, Wright SI (2016) The Limits of Natural Selection in a Nonequilibrium World. Trends in Genetics, 32, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.004 | How much does Ne vary among species? | Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle | <p>Genetic drift is an important evolutionary force of strength inversely proportional to *Ne*, the effective population size. The impact of drift on genome diversity and evolution is known to vary among species, but quantifying this effect is a d... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Martin Lascoux | 2019-12-08 00:11:00 | View | |

20 Dec 2017

Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiationNicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias 10.1101/148189The influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification, revealed by Neotropical butterfliesRecommended by Richard H Ree based on reviews by Delano Lewis and 1 anonymous reviewerThe influence of environmental change over geological time on the tempo and mode of biological diversification is a hot topic in biogeography. Of central interest are questions about where, when, and how fast lineages proliferated, suffered extinction, and migrated in response to tectonic events, the waxing and waning of dominant biomes, etc. In this context, the dynamic conditions of the Miocene have received much attention, from studies of many clades and biogeographic regions. Here, Chazot et al. [1] present an exemplary analysis of butterflies (tribe Ithomiini) in the Neotropics, examining their diversification across the Andes and Amazon. They infer sharp contrasts between these regions in the late Miocene: accelerated diversification during orogeny of the Andes, and greater extinction in the Amazon associated during the Pebas system, with interchange and local diversification increasing following the Pebas during the Pliocene. References [1] Chazot N, Willmott KR, Lamas G, Freitas AVL, Piron-Prunier F, Arias CF, Mallet J, De-Silva DL and Elias M. 2017. Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation. BioRxiv 148189, ver 4 of 19th December 2017. doi: 10.1101/148189 [2] Xing Y, and Ree RH. 2017. Uplift-driven diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a temperate biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114: E3444-E3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616063114 | Renewed diversification following Miocene landscape turnover in a Neotropical butterfly radiation | Nicolas Chazot, Keith R. Willmott, Gerardo Lamas, André V.L. Freitas, Florence Piron-Prunier, Carlos F. Arias, James Mallet, Donna Lisa De-Silva, Marianne Elias | The Neotropical region has experienced a dynamic landscape evolution throughout the Miocene, with the large wetland Pebas occupying western Amazonia until 11-8 my ago and continuous uplift of the Andes mountains along the western edge of South Ame... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Richard H Ree | 2017-06-12 11:55:14 | View | |

30 Aug 2021

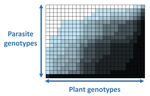

The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactionsMoury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Juliette, Fabre Frédéric, Fournet Sylvain, Grimault Valérie, Jaunet Thierry, Justafré Isabelle, Lefebvre Véronique, Losdat Denis, Marcel Thierry C., Montarry Josselin, Morris Cindy E., Omrani Mariem, Paineau Manon, Perrot Sophie, Pilet-Nayel Marie-Laure, R... https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745Nestedness and modularity in plant-parasite infection networksRecommended by Santiago Elena based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers

In a landmark paper, Flores et al. (2011) showed that the interactions between bacteria and their viruses could be nicely described using a bipartite infection networks. Two quantitative properties of these networks were of particular interest, namely modularity and nestedness. Modularity emerges when groups of host species (or genotypes) shared groups of viruses. Nestedness provided a view of the degree of specialization of both partners: high nestedness suggests that hosts differ in their susceptibility to infection, with some highly susceptible host genotypes selecting for very specialized viruses while strongly resistant host genotypes select for generalist viruses. Translated to the plant pathology parlance, this extreme case would be equivalent to a gene-for-gene infection model (Flor 1956): new mutations confer hosts with resistance to recently evolved viruses while maintaining resistance to past viruses. Likewise, virus mutations for expanding host range evolve without losing the ability to infect ancestral host genotypes. By contrast, a non-nested network would represent a matching-allele infection model (Frank 2000) in which each interacting organism evolves by losing its capacity to resist/infect its ancestral partners, resembling a Red Queen dynamic. Obviously, the reality is more complex and may lie anywhere between these two extreme situations. Recently, Valverde et al. (2020) developed a model to explain the emergence of nestedness and modularity in plant-virus infection networks across diverse habitats. They found that local modularity could coexist with global nestedness and that intraspecific competition was the main driver of the evolution of ecosystems in a continuum between nested-modular and nested networks. These predictions were tested with field data showing the association between plant host species and different viruses in different agroecosystems (Valverde et al. 2020). The effect of interspecific competition in the structure of empirical plant host-virus infection networks was also tested by McLeish et al. (2019). Besides data from agroecosystems, evolution experiments have also shown the pervasive emergence of nestedness during the diversification of independently-evolved lineages of potyviruses in Arabidopsis thaliana genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection (Hillung et al. 2014; González et al. 2019; Navarro et al. 2020). In their study, Moury et al. (2021) have expanded all these previous observations to a diverse set of pathosystems that range from viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes to insects. While modularity was barely seen in only a few of the systems, nestedness was a common trend (observed in ~94% of all systems). This nestedness, as seen in previous studies and as predicted by theory, emerged as a consequence of the existence of generalist and specialist strains of the parasites that differed in their capacity to infect more or less resistant plant genotypes. As pointed out by Moury et al. (2021) in their conclusions, the ubiquity of nestedness in plant-parasite infection matrices has strong implications for the evolution and management of infectious diseases. References Flor, H. H. (1956). The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics, 8, 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8 Flores, C. O., Meyer, J. R., Valverde, S., Farr, L., and Weitz, J. S. (2011). Statistical structure of host–phage interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, E288-E297. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101595108 Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 202, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054 González, R., Butković, A., and Elena, S. F. (2019). Role of host genetic diversity for susceptibility-to-infection in the evolution of virulence of a plant virus. Virus evolution, 5(2), vez024. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez052 Hillung, J., Cuevas, J. M., Valverde, S., and Elena, S. F. (2014). Experimental evolution of an emerging plant virus in host genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection. Evolution, 68, 2467-2480. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12458 McLeish, M., Sacristán, S., Fraile, A., and García-Arenal, F. (2019). Coinfection organizes epidemiological networks of viruses and hosts and reveals hubs of transmission. Phytopathology, 109, 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0293-R Moury B, Audergon J-M, Baudracco-Arnas S, Krima SB, Bertrand F, Boissot N, Buisson M, Caffier V, Cantet M, Chanéac S, Constant C, Delmotte F, Dogimont C, Doumayrou J, Fabre F, Fournet S, Grimault V, Jaunet T, Justafré I, Lefebvre V, Losdat D, Marcel TC, Montarry J, Morris CE, Omrani M, Paineau M, Perrot S, Pilet-Nayel M-L and Ruellan Y (2021) The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433745, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745 Navarro, R., Ambros, S., Martinez, F., Wu, B., Carrasco, J. L., and Elena, S. F. (2020). Defects in plant immunity modulate the rates and patterns of RNA virus evolution. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.13.337402 Valverde, S., Vidiella, B., Montañez, R., Fraile, A., Sacristán, S., and García-Arenal, F. (2020). Coexistence of nestedness and modularity in host–pathogen infection networks. Nature ecology & evolution, 4, 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1130-9 | The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions | Moury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Jul... | <p>Understanding the relationships between host range and pathogenicity for parasites, and between the efficiency and scope of immunity for hosts are essential to implement efficient disease control strategies. In the case of plant parasites, most... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Species interactions | Santiago Elena | 2021-03-04 21:23:08 | View | |

22 May 2017

Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans?Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon 10.1101/108589A new hypothesis to explain Ebola's high virulenceRecommended by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart based on reviews by Virginie Ravigné and François Blanquart

The tragic 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak that resulted in more than 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths in West Africa [1] has been a surprise to the scientific community. Before 2013, the Ebola virus (EBOV) was known to produce recurrent outbreaks in remote villages near tropical rainforests in Central Africa, never exceeding a few hundred cases with very high virulence. Both EBOV’s ability to circulate for several months in large urban human populations and its important mutation rate suggest that EBOV’s virulence could evolve and to some extent adapt to human hosts [2]. Up to now, the high virulence of EBOV in humans was generally thought to be maladaptive, the virus being adapted to circulating in wild animal populations (e.g. fruit bats [3]). As a logical consequence, EBOV virulence could be expected to decrease during long epidemics in humans. The present paper by Sofonea et al. [4] challenges this view and explores how, given EBOV’s life cycle and known epidemiological parameters, virulence is expected to evolve in the human host during long epidemics. The main finding of the paper is that there is no chance that EBOV’s virulence decreases in the short and long terms. The main underlying mechanism is that EBOV is also transmitted by dead bodies, which limits the cost of virulence. In itself the idea that selection should select for higher virulence in diseases that are also transmitted after host death will sound intuitive for most evolutionary epidemiologists. The accomplishment of the paper is to make a very strong case that the parameter range where virulence could decrease is very small. The paper further provides scientifically grounded arguments in favor of the safe management of corpses. Safe burial of corpses is culturally difficult to impose. The present paper shows that in addition to instantaneously decreasing the spread of the virus, safe burial may limit virulence increase in the short term and favor of less virulent strains in the long term. Altogether these results make a timely and important contribution to the knowledge and understanding of EBOV. References [1] World Health Organization. 2016. WHO: Ebola situation report - 10 June 2016. [2] Kupferschmidt K. 2014. Imagining Ebola’s next move. Science 346: 151–152. doi: 10.1126/science.346.6206.151 [3] Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska, Gonzalez JP and Swanepoel R. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438: 575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a [4] Sofonea MT, Aldakak L, Boullosa LFVV and Alizon S. 2017. Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? bioRxiv 108589, ver. 3 of 19th May 2017; doi: 10.1101/108589 | Can Ebola Virus evolve to be less virulent in humans? | Mircea T. Sofonea, Lafi Aldakak, Luis Fernando Boullosa, Samuel Alizon | Understanding Ebola Virus (EBOV) virulence evolution is not only timely but also raises specific questions because it causes one pf the most virulent human infections and it is capable of transmission after the death of its host. Using a compartme... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology | Virginie Ravigné | 2017-02-15 13:25:58 | View | |

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View | |

23 Nov 2020

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mitesMiguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilitiesRecommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewerCytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020). References Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543 | Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer

, where Ne is the effective population size and

, where Ne is the effective population size and  is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common

is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common  . Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.

. Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.