How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans?

Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030

Be careful when studying selection based on polygenic score overdispersion

Recommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been a great promise for our understanding of the connection between genotype and phenotype. Today, the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog contains 251,401 associations from 4,961 studies (1). This wealth of studies has also generated interest to use the summary statistics beyond the few top hits in order to make predictions for individuals without known phenotype, e.g. to predict polygenic risk scores or to study polygenic selection by comparing different groups. For instance, polygenic selection acting on the most studied polygenic trait, height, has been subject to multiple studies during the past decade (e.g. 2–6). They detected north-south gradients in Europe which were consistent with expectations. However, their GWAS summary statistics were based on the GIANT consortium data set, a meta-analysis of GWAS conducted in different European cohorts (7,8). The availability of large data sets with less stratification such as the UK Biobank (9) has led to a re-evaluation of those results. The nature of the GIANT consortium data set was realized to represent a potential problem for studies of polygenic adaptation which led several of the authors of the original articles to caution against the interpretations of polygenic selection on height (10,11). This was a great example on how the scientific community assessed their own earlier results in a critical way as more data became available. At the same time it left the question whether there is detectable polygenic selection separating populations more open than ever.

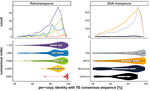

Generally, recent years have seen several articles critically assessing the portability of GWAS results and risk score predictions to other populations (12–14). Refoyo-Martínez et al. (15) are now presenting a systematic assessment on the robustness of cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans. They compiled GWAS results for complex traits which have been studied in more than one cohort and then use allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes Project data (16) set to detect signals of polygenic score overdispersion. As the source for the allele frequencies is kept the same across all tests, differences between the signals must be caused by the underlying GWAS. The results are concerning as the level of overdispersion largely depends on the choice of GWAS cohort. Cohorts with homogenous ancestries show little to no overdispersion compared to cohorts of mixed ancestries such as meta-analyses. It appears that the meta-analyses fail to fully account for stratification in their data sets.

The authors based most of their analyses on the heavily studied trait height. Additionally, they use educational attainment (measured as the number of school years of an individual) as an example. This choice was due to the potential over- or misinterpretation of results by the media, the general public and by far right hate groups. Such traits are potentially confounded by unaccounted cultural and socio-economic factors. Showing that previous results about polygenic selection on educational attainment are not robust is an important result that needs to be communicated well. This forms a great example for everyone working in human genomics. We need to be aware that our results can sometimes be misinterpreted. And we need to make an effort to write our papers and communicate our results in a way that is honest about the limitations of our research and that prevents the misuse of our results by hate groups.

This article represents an important contribution to the field. It is cruicial to be aware of potential methodological biases and technical artifacts. Future studies of polygenic adaptation need to be cautious with their interpretations of polygenic score overdispersion. A recommendation would be to use GWAS results obtained in homogenous cohorts. But even if different biobank-scale cohorts of homogeneous ancestry are employed, there will always be some remaining risk of unaccounted stratification. These conclusions may seem sobering but they are part of the scientific process. We need additional controls and new, different methods than polygenic score overdispersion for assessing polygenic selection. Last year also saw the presentation of a novel approach using sequence data and GWAS summary statistics to detect directional selection on a polygenic trait (17). This new method appears to be robust to bias stemming from stratification in the GWAS cohort as well as other confounding factors. Such new developments show light at the end of the tunnel for the use of GWAS summary statistics in the study of polygenic adaptation.

References

1. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1005–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1120

2. Turchin MC, Chiang CW, Palmer CD, Sankararaman S, Reich D, Hirschhorn JN. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs. Nature Genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):1015–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2368

3. Berg JJ, Coop G. A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2014 Aug 7;10(8):e1004412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004412

4. Robinson MR, Hemani G, Medina-Gomez C, Mezzavilla M, Esko T, Shakhbazov K, et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nature Genetics. 2015 Nov;47(11):1357–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3401

5. Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015 Dec;528(7583):499–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152

6. Racimo F, Berg JJ, Pickrell JK. Detecting polygenic adaptation in admixture graphs. Genetics. 2018. Arp;208(4):1565–1584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300489

7. Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7317):832–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09410

8. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014 Nov;46(11):1173–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097

9. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z

10. Berg JJ, Harpak A, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Joergensen AM, Mostafavi H, Field Y, et al. Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39725. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39725

11. Sohail M, Maier RM, Ganna A, Bloemendal A, Martin AR, Turchin MC, et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39702. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39702

12. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics. 2019 Apr;51(4):584–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x

13. Bitarello BD, Mathieson I. Polygenic Scores for Height in Admixed Populations. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):4027–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401658

14. Uricchio LH, Kitano HC, Gusev A, Zaitlen NA. An evolutionary compass for detecting signals of polygenic selection and mutational bias. Evolution Letters. 2019;3(1):69–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.97

15. Refoyo-Martínez A, Liu S, Jørgensen AM, Jin X, Albrechtsen A, Martin AR, Racimo F. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? bioRxiv, 2021, 2020.07.13.200030, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030

16. Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Sep 30;526(7571):68–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393

17. Stern AJ, Speidel L, Zaitlen NA, Nielsen R. Disentangling selection on genetically correlated polygenic traits using whole-genome genealogies. bioRxiv. 2020 May 8;2020.05.07.083402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.083402

| How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? | Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo | <p>Over the past decade, summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been used to detect and quantify polygenic adaptation in humans. Several studies have reported signatures of natural selection at sets of SNPs associated... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genetic conflicts, Human Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | | 2020-08-14 15:06:54 | View |

Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity

Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.092775

The push and pull between theory and data in understanding the dynamics of invasion

Recommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Laura Naslund and 2 anonymous reviewers

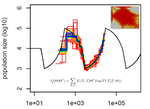

Exciting times are afoot for those of us interested in the ecology and evolution of invasive populations. Recent years have seen evolutionary process woven firmly into our understanding of invasions (Miller et al. 2020). This integration has inspired a welter of empirical and theoretical work. We have moved from field observations and verbal models to replicate experiments and sophisticated mathematical models. Progress has been rapid, and we have seen science at its best; an intimate discussion between theory and data.

An area currently under very active development is our understanding of pushed invasions. Here a population spreads through space driven, not by dispersal and growth originating at the leading tip of the invasion, but by dispersal and growth originating deeper in the bulk of the population. These pushed invasions may be quite common – they result when per capita growth and dispersal rates are higher in the bulk of the wave than at the leading tip. They result from a range of well-known phenomena, including Allee effects and density-dependent dispersal (Gandhi et al. 2016; Bîrzu et al. 2019). Pushed invasions travel faster than we would expect given growth and dispersal rates on the leading tip, and they lose genetic diversity more slowly than classical pulled invasions (Roques et al. 2012; Haond et al. 2018; Bîrzu et al. 2019).

Well… in theory, anyway. The theory on pushed waves has momentarily streaked ahead of the empirical work, because empirical systems for studying pushed invasions are rare (though see Gandhi et al. 2016; Gandhi, Korolev, and Gore 2019). In this paper, Dahirel and colleagues (2020) make the argument that we may be able to generate pushed invasions in laboratory systems simply by reducing the connectedness of our experimental landscapes. If true, we might have a simple tool for turning many of our established experimental systems into systems for studying pushed dynamics.

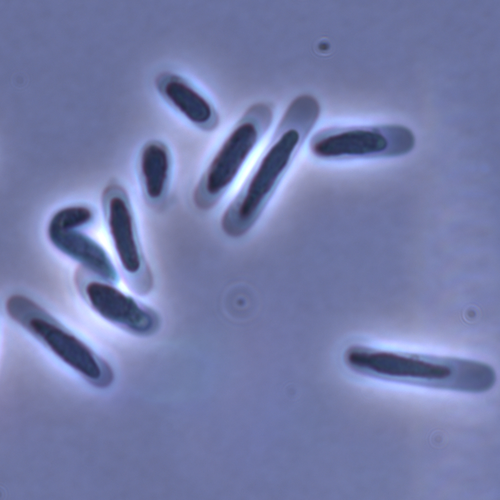

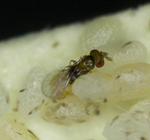

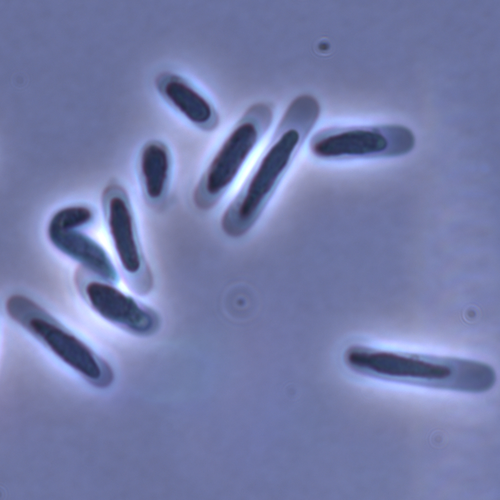

It’s a nice idea, and the paper goes to careful lengths to explore the possibility in their lab system (a parasitoid wasp, Trichogramma). They run experiments on replicate wasp populations comparing strongly- v poorly-connected arrays, and estimate the resulting invasion speeds and rate of diversity loss. They also build a simulation model of the system, allowing them to explore in-silico a range of possible processes underlying their results.

As well as developing these parallel systems, Dahirel and colleagues (2020) go to careful lengths to develop statistical analyses that allow inference on key parameters, and they apply these analyses to both the experimental and simulation data. They have been motivated to apply methods that might be used in both laboratory and field settings to help classify invasions.

Ultimately, they found reasonable evidence that their poorly-connected habitat did induce a pushed dynamic. Their poorly connected invasions travelled faster than they should have if they were pulled, they lost diversity more slowly than the highly connected habitat, and replicates with a higher carrying capacity tended to have higher invasion speeds. All in line with expectations of a pushed dynamic. Interestingly, however, their simulation results suggest that they probably got this perfect result for unexpected reasons. The strong hint is that their poorly-connected habitat induced density dependent dispersal in the wasps. Without this effect, their simulations suggest they should have seen diversity decreasing much more rapidly than it did.

There is a nuanced, thoughtful, and carefully argued discussion about all this in the paper, and it is worth reading. There is much of value in this paper. Theirs is not a perfect empirical system in which all the model assumptions are met and in which huge population sizes make stochastic effects negligible. Here is a system one step closer to the messy reality of biology. The struggle to align this system with new theory has been worth the effort. Not only does it give us hope that we might usefully be able to discriminate between classes of invasions using real-world data, but it hints at a rule that Tolstoy might have expressed this way: all pulled invasions are alike, each pushed invasion is pushed in its own way.

References

Bîrzu, G., Matin, S., Hallatschek, O., and Korolev, K. S. (2019). Genetic drift in range expansions is very sensitive to density dependence in dispersal and growth. Ecology Letters, 22(11), 1817-1827. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13364

Dahirel, M., Bertin, A., Haond, M., Blin, A., Lombaert, E., Calcagno, V., Fellous, S., Mailleret, L., Malausa, T., and Vercken, E. (2020). Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. bioRxiv, 2020.05.13.092775, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.092775

Gandhi, S. R., Korolev, K. S., and Gore, J. (2019). Cooperation mitigates diversity loss in a spatially expanding microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(47), 23582-23587. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910075116

Gandhi, S. R., Yurtsev, E. A., Korolev, K. S., and Gore, J. (2016). Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(25), 6922-6927. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113

Haond, M., Morel-Journel, T., Lombaert, E., Vercken, E., Mailleret, L. and Roques, L. (2018). When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation (2018), bioRxiv, 307322, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/307322

Miller et al. (2020). Eco‐evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101(10), e03139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139

Roques, L., Garnier, J., Hamel, F., and Klein, E. K. (2012). Allee effect promotes diversity in traveling waves of colonization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(23), 8828-8833. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1201695109

| Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Marjorie Haond, Aurélie Blin, Eric Lombaert, Vincent Calcagno, Simon Fellous, Ludovic Mailleret, Thibaut Malausa, Elodie Vercken | <p>Range expansions are key processes shaping the distribution of species; their ecological and evolutionary dynamics have become especially relevant today, as human influence reshapes ecosystems worldwide. Many attempts to explain and predict ran... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Ben Phillips | | 2020-08-04 12:51:56 | View |

Y chromosome makes fruit flies die younger

Recommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina Vieira

In most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018).

The relative contributions of these different effects to SGLs remain unknown. Sex-differences in life history strategies have been considered as the most important cause of SGLs for long (Tidière et al. 2015) but this effect remain equivocal (Lemaître et al. 2020) and cannot explain alone the diversity of patterns observed across species (Marais et al. 2018). Similarly, while studies in Drosophila and humans have shown that the mother’s curse contributes to SGLs in those organisms (e.g. Milot et al. 2007), its contribution may not be strong. Recently, two large-scale comparative analyses have shown that in species with XY chromosomes males show a shorter lifespan compared to females, while in species with ZW chromosomes (a system in which the female are the heterogametic sex and are ZW, and the males ZZ) the opposite pattern is observed (Pipoly et al. 2015; Xirocostas et al. 2020). Apart from these correlational studies, very little experimental tests of the effect of sex chromosomes on longevity have been conducted. In Drosophila, the evidence suggests that the unguarded X effect does not contribute to SGLs (Brengdahl et al. 2018). Whether a toxic Y effect exists in this species was unknown.

In a very elegant study, Brown et al. (2020) provided strong evidence for such a toxic Y effect in Drosophila melanogaster. First, they checked that in the D. melanogaster strain that they were studying (Canton-S), males were indeed dying younger than females. They also confirmed that in this strain, as in others, the male genomes include more repeats and heterochromatin than the female ones using cytometry. A careful analysis of the heterochromatin (using H3K9me2, a repressive histone modification typical of heterochromatin, as a proxy) in old flies revealed that heterochromatin loss was much more important in males than in females, in particular on the Y chromosome (but also to a lesser extent at the pericentromric regions of the autosomes). This change in heterochromatin had two outputs, they found. First, the expression of the genes in those regions was affected. They highlighted that many of such genes are involved in immunity and regulation with a potential impact on longevity. Second, they found a striking TE reactivation. These two effects were stronger in males. While females showed clear reactivation of 6 TEs, with the total fraction of repeats in the transcriptome going from 2% (young females) to 4.6% (old females), males experienced the reactivation of 32 TEs, with the total fraction of repeats in the transcriptome going from 1.6% (young males) to 5.8% (old males). It appeared that most of these TEs are Y-linked. And when focusing on Y-linked repeats, they found that 32 Y-linked TEs became upregulated during male aging and the fraction of Y-linked TEs in the transcriptome increased ninefold.

All these observations clearly suggested that male longevity was decreased because of a toxic Y effect. To really uncover a causal relationship between having a Y chromosome and shorter longevity, Brown et al. (2020) artificially produced flies with atypical karyotypes: X0 males, XXY females and XYY males. This is very interesting as they could uncouple the effect of the phenotypical sex (being male or female) and having a Y chromosome or not, as in fruit flies sex is determined not by the Y chromosome but by the X/autosome ratio. Their results are striking. They found that longevity of the X0 males was the highest (higher than XX females in fact), and that of the XYY males the lowest. Females XXY had intermediate longevities. Importantly, this was found to be robust to genomic background as results were the same using crosses from different strains. When analysing TEs of these flies, they found a particularly strong expression of the Y-linked TEs in old XXY and XYY flies. Interestingly, in young XXY and XYY flies Y-linked TEs expression was also strong, suggesting the chromatin regulation of the Y chromosome is disrupted in these flies.

This work points to the idea that SGLs in D. melanogaster are mainly explained by the toxic Y effect. The molecular details however remain to be elucidated. The effect of the Y chromosome on aging might be more complex than envisioned in the toxic Y model presented above. Brown et al. (2020) indeed found that heterochromatin loss was globally faster in males, both at the Y chromosome and the autosomes. The organisation of the nucleus, in particular of the nucleolus, which is involved in heterochromatin maintenance, involves the sex chromosomes in D. melanogaster as discussed in the paper, and may explain this observation. The epigenetic status of the Y chromosome is known to affect that of all the autosomes in Drosophila (Lemos et al. 2008). Also, in Brown et al. (2020) most of the work (in particular the genomic part) has been done on Canton-S. Only D. melanogaster was studied but limited data suggest different Drosophila species may have different SGLs. The TE analysis is known to be tricky, different tools to analyse TE expression exist (e.g. Lerat et al. 2017; Lanciano and Cristofari 2020). Future work should focus on testing the toxic Y effect on other D. melanogaster strains and other Drosophila species, using different tools to study TE expression, and on dissecting the molecular details of the toxic Y effect.

References

Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472

Brengdahl, M., Kimber, C. M., Maguire-Baxter, J., and Friberg, U. (2018). Sex differences in life span: Females homozygous for the X chromosome do not suffer the shorter life span predicted by the unguarded X hypothesis. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution, 72(3), 568–577. 10.1111/evo.13434

Brown, E. J., Nguyen, A. H., and Bachtrog, D. (2020). The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila. Nature ecology and evolution, 4(6), 853–862. 10.1038/s41559-020-1179-5 or preprint link on bioRxiv

Frank, S. A., and Hurst, L. D. (1996). Mitochondria and male disease. Nature, 383(6597), 224. 10.1038/383224a0

Lanciano, S., and Cristofari, G. (2020). Measuring and interpreting transposable element expression. Nature reviews. Genetics, 10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y. Advance online publication. 10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y

Lemaître, J. F., Ronget, V., Tidière, M., Allainé, D., Berger, V., Cohas, A., Colchero, F., Conde, D. A., Garratt, M., Liker, A., Marais, G., Scheuerlein, A., Székely, T., and Gaillard, J. M. (2020). Sex differences in adult lifespan and aging rates of mortality across wild mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(15), 8546–8553. 10.1073/pnas.1911999117

Lemos, B., Araripe, L. O., and Hartl, D. L. (2008). Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences. Science (New York, N.Y.), 319(5859), 91–93. 10.1126/science.1148861

Lerat, E., Fablet, M., Modolo, L., Lopez-Maestre, H., and Vieira, C. (2017). TEtools facilitates big data expression analysis of transposable elements and reveals an antagonism between their activity and that of piRNA genes. Nucleic acids research, 45(4), e17. 10.1093/nar/gkw953

Marais, G., Gaillard, J. M., Vieira, C., Plotton, I., Sanlaville, D., Gueyffier, F., and Lemaitre, J. F. (2018). Sex gap in aging and longevity: can sex chromosomes play a role?. Biology of sex differences, 9(1), 33. 10.1186/s13293-018-0181-y

Milot, E., Moreau, C., Gagnon, A., Cohen, A. A., Brais, B., and Labuda, D. (2017). Mother's curse neutralizes natural selection against a human genetic disease over three centuries. Nature ecology and evolution, 1(9), 1400–1406. 10.1038/s41559-017-0276-6

Pipoly, I., Bókony, V., Kirkpatrick, M., Donald, P. F., Székely, T., and Liker, A. (2015). The genetic sex-determination system predicts adult sex ratios in tetrapods. Nature, 527(7576), 91–94. 10.1038/nature15380

Tidière, M., Gaillard, J. M., Müller, D. W., Lackey, L. B., Gimenez, O., Clauss, M., and Lemaître, J. F. (2015). Does sexual selection shape sex differences in longevity and senescence patterns across vertebrates? A review and new insights from captive ruminants. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution, 69(12), 3123–3140. 10.1111/evo.12801

Xirocostas, Z. A., Everingham, S. E., and Moles, A. T. (2020). The sex with the reduced sex chromosome dies earlier: a comparison across the tree of life. Biology letters, 16(3), 20190867. 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0867

| The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View |

Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent

Recommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome.

A key framework for such modelling of local tMRCA tracts along genomes is the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) (McVean and Cardin 2005, Marjoram and Wall 2006) . The problem that the SMC solves is that the mosaic of local tMRCAs along the genome is unknown, both in their actual ages and in their positions along the genome. The SMC allows to effectively sum across all possibilities and handle the uncertainty probabilistically. Several important tools for inferring the demographic history of a population have been developed built on top of the SMC, including PSMC (Li and Durbin 2011), diCal (Sheehan et al 2013), MSMC (Schiffels and Durbin 2014), SMC++ (Terhorst et al 2017), eSMC (Sellinger et al. 2020) and others.

In this paper, Sellinger, Abu Awad and Tellier (2020) review these SMC-based methods and provide a coherent simulation design to comparatively assess their strengths and weaknesses in a variety of demographic scenarios (Sellinger, Abu Awad and Tellier 2020). In addition, they used these simulations to test how breaking various key assumptions in SMC methods affects estimates, such as constant recombination rates, or absence of false positive SNP calls.

As a result of this assessment, the authors not only provide practical guidance for researchers who want to use these methods, but also insights into how these methods work. For example, the paper carefully separates sources of error in these methods by observing what they call “Best-case convergence” of each method if the data behaves perfectly and separating that from how the method applies with actual data. This approach provides a deeper insight into the methods than what we could learn from application to genomic data alone.

In the age of genomics, computational tools and their development are key for researchers in this field. All the more important is it to provide the community with overviews, reviews and independent assessments of such tools. This is particularly important as sometimes the development of new methods lacks primary visibility due to relevant testing material being pushed to Supplementary Sections in papers due to space constraints. As SMC-based methods have become so widely used tools in genomics, I think the detailed assessment by Sellinger et al. (2020) is timely and relevant.

In conclusion, I recommend this paper because it bridges from a mere review of the different methods to an in-depth assessment of performance, thereby addressing both beginners in the field who just seek an initial overview, as well as experienced researchers who are interested in theoretical boundaries and assumptions of the different methods.

References

[1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231

[2] Marjoram, P., and Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast"" coalescent"" simulation. BMC genetics, 7(1), 16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16

[3] McVean, G. A., and Cardin, N. J. (2005). Approximating the coalescent with recombination. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1459), 1387-1393. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1673

[4] Schiffels, S., and Durbin, R. (2014). Inferring human population size and separation history from multiple genome sequences. Nature genetics, 46(8), 919-925. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3015

[5] Sellinger, T. P. P., Awad, D. A., Moest, M., and Tellier, A. (2020). Inference of past demography, dormancy and self-fertilization rates from whole genome sequence data. PLoS Genetics, 16(4), e1008698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008698

[6] Sellinger, T. P. P., Awad, D. A. and Tellier, A. (2020) Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent. bioRxiv, 2020.07.23.217091, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091

[7] Sheehan, S., Harris, K., and Song, Y. S. (2013). Estimating variable effective population sizes from multiple genomes: a sequentially Markov conditional sampling distribution approach. Genetics, 194(3), 647-662. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.149096

[8] Terhorst, J., Kamm, J. A., and Song, Y. S. (2017). Robust and scalable inference of population history from hundreds of unphased whole genomes. Nature genetics, 49(2), 303-309. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3748

| Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites

Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699

Speciation in spider mites: disentangling the roles of Wolbachia-induced vs. nuclear mating incompatibilities

Recommended by Jan Engelstaedter based on reviews by Wolfgang Miller and 1 anonymous reviewer

Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is a mating incompatibility that is induced by maternally inherited endosymbionts in many arthropods. These endosymbionts include, most famously, the alpha-proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis (Yen & Barr 1971; Werren et al. 2008) but also the Bacteroidetes bacterium Cardinium hertigii (Zchori-Fein et al. 2001), a gamma-proteobacterium of the genus Rickettsiella (Rosenwald et al. 2020) and another, as yet undescribed alpha-proteobacterium (Takano et al. 2017). CI manifests as embryonic mortality in crosses between infected males and females that are uninfected or infected with a different strain, whereas embryos develop normally in all other crosses. This phenotype may enable the endosymbionts to spread rapidly within their host population. Exploiting this, CI-inducing Wolbachia are being harnessed to control insect-borne diseases (e.g., O'Neill 2018). Much progress elucidating the genetic basis and developmental mechanism of CI has been made in recent years, but many open questions remain (Shropshire et al. 2020).

Immediately following the discovery and early study of CI in mosquitoes, Laven (1959, 1967) proposed that CI could be an important driver of speciation. Indeed, bi-directional CI can strongly reduce gene flow between two populations due to the elimination of F1 embryos, so that CI can act as a trigger for genetic differentiation in the host (Telschow et al. 2002, 2005). This idea has received much attention, and a potential role for CI in incipient speciation has been demonstrated in several species (e.g., Bordenstein et al. 2001; Jaenike et al. 2006). However, we still don’t know how commonly CI actually triggers speciation, rather than being merely a minor player or secondary phenomenon. The problem is that in addition to CI, postzygotic reproductive isolation can also be caused by host-induced, nuclear incompatibilities. Determining the relative contributions of these two causes of isolation is difficult and has rarely been done.

The study by Cruz et al. (2020) addresses this problem head-on, using a study system of Tetranychus urticae spider mites. These cosmopolitan mites are infected with different strains of Wolbachia. They come in two different colour forms (red and green) that can co-occur sympatrically on the same host plant but exhibit various degrees of reproductive isolation. A complicating factor in spider mites is that they are haplodiploid: unfertilised eggs develop into haploid males and are therefore not affected by any postzygotic incompatibilities, whereas fertilised eggs normally develop into diploid females. In haplodiploids, Wolbachia-induced CI can either kill diploid embryos (as in diplodiploid species), or turn them into haploid males. In their study, Cruz et al. used three different populations (one of the green and two of the red form) and employed a full factorial experiment involving all possible combinations of crosses of Wolbachia infected or uninfected males and females. For each cross, they measured F1 embryonic and juvenile mortality as well as sex ratio, and they also measured F1 fertility and F2 viability. Their results showed that there is strong reduction in hybrid female production caused by Wolbachia-induced CI. However, independent of this and through a different mechanism, there is an even stronger reduction in hybrid production caused by host-associated incompatibilities. In combination with the also observed near-complete sterility of F1 hybrid females and full F2 hybrid breakdown (neither of which is caused by Wolbachia), the results indicate essentially complete reproductive isolation between the green and red forms of T. urticae.

Overall, this is an elegant study with an admirably clean and comprehensive experimental design. It demonstrates that Wolbachia can contribute to reproductive isolation between populations, but that host-induced mechanisms of reproductive isolation predominate in these spider mite populations. Further studies in this exiting system would be useful that also investigate the contribution of pre-zygotic isolation mechanisms such as assortative mating, ascertain whether the results can be generalised to other populations, and – most challengingly – establish the order in which the different mechanisms of reproductive isolation evolved.

References

Bordenstein, S. R., O'Hara, F. P., and Werren, J. H. (2001). Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature, 409(6821), 707-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/35055543

Cruz, M. A., Magalhães, S., Sucena, É., and Zélé, F. (2020) Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites. bioRxiv, 2020.06.29.178699, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.29.178699

Jaenike, J., Dyer, K. A., Cornish, C., and Minhas, M. S. (2006). Asymmetrical reinforcement and Wolbachia infection in Drosophila. PLoS Biol, 4(10), e325. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040325

Laven, H. (1959). SPECIATION IN MOSQUITOES Speciation by Cytoplasmic Isolation in the Culex Pipiens-Complex. In Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology (Vol. 24, pp. 166-173). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Laven, H. (1967). A possible model for speciation by cytoplasmic isolation in the Culex pipiens complex. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 37(2), 263-266.

O’Neill S.L. (2018) The Use of Wolbachia by the World Mosquito Program to Interrupt Transmission of Aedes aegypti Transmitted Viruses. In: Hilgenfeld R., Vasudevan S. (eds) Dengue and Zika: Control and Antiviral Treatment Strategies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1062. Springer, Singapore. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8727-1_24

Rosenwald, L.C., Sitvarin, M.I. and White, J.A. (2020). Endosymbiotic Rickettsiella causes cytoplasmic incompatibility in a spider host. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1107

Shropshire, J. D., Leigh, B., and Bordenstein, S. R. (2020). Symbiont-mediated cytoplasmic incompatibility: what have we learned in 50 years?. Elife, 9, e61989. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.61989

Takano et al. (2017). Unique clade of alphaproteobacterial endosymbionts induces complete cytoplasmic incompatibility in the coconut beetle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 6110-6115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1618094114

Telschow, A., Hammerstein, P., and Werren, J. H. (2002). The effect of Wolbachia on genetic divergence between populations: models with two-way migration. the american naturalist, 160(S4), S54-S66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/342153

Telschow, A., Hammerstein, P., and Werren, J. H. (2005). The effect of Wolbachia versus genetic incompatibilities on reinforcement and speciation. Evolution, 59(8), 1607-1619. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01812.x

Werren, J. H., Baldo, L., and Clark, M. E. (2008). Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 6(10), 741-751. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1969

Yen, J. H., and Barr, A. R. (1971). New hypothesis of the cause of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens L. Nature, 232(5313), 657-658. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/232657a0

Zchori-Fein, E., Gottlieb, Y., Kelly, S. E., Brown, J. K., Wilson, J. M., Karr, T. L., and Hunter, M. S. (2001). A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(22), 12555-12560. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.221467498

| Wolbachia and host intrinsic reproductive barriers contribute additively to post-mating isolation in spider mites | Miguel A. Cruz, Sara Magalhães, Élio Sucena, Flore Zélé | <p>Wolbachia are widespread maternally-inherited bacteria suggested to play a role in arthropod host speciation through induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility, but this hypothesis remains controversial. Most studies addressing Wolbachia-induced ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Life History, Reproduction and Sex, Speciation, Species interactions | Jan Engelstaedter | | 2020-07-09 10:18:28 | View |

A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection

Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Philippe David

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741

Identification of a gene cluster amplification associated with organophosphate insecticide resistance: from the diversity of the resistance allele complex to an efficient field detection assay

Recommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Diego Ayala and 2 anonymous reviewers

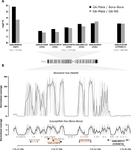

The emergence and spread of insecticide resistance compromises the efficiency of insecticides as prevention tool against the transmission of insect-transmitted diseases (Moyes et al. 2017). In this context, the understanding of the genetic mechanisms of resistance and the way resistant alleles spread in insect populations is necessary and important to envision resistance management policies. A common and important mechanism of insecticide resistance is gene amplification and in particular amplification of insecticide detoxification genes, which leads to the overexpression of these genes (Bass & Field, 2011). Cattel and coauthors (2020) adopt a combination of experimental approaches to study the role of gene amplification in resistance to organophosphate insecticides in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and its occurrence in populations of South East Asia and to develop a molecular test to track resistance alleles.

Their first approach consists in performing an artificial selection on laboratory Ae. Aegypti populations started with individuals collected in Laos. In the selected population, an initial 90% mortality by adult exposure to the organophosphate insecticide malathion is imposed. This population shows a steep increase in resistance to malathion and other organophosphate insecticides, which is absent in the paired control population. The transcriptomic patterns of the control and the evolved populations as well as of a reference sensitive population reveals, among other differences, the over-expression of five carboxy/choline esterase (CCE) genes in the insecticide selected population. These five genes happen to be clustered in the Ae. aegypti genome and whole genome sequencing of a highly resistant population combined to qPCR test on genomic DNA showed that the overexpression of these genes is due to gene amplification. Although it would have been more elegant to have replicate selected and control populations and to perform the transcriptomic and the genomic analyses directly on the experimental populations, the authors gather a set of experimental evidence which combined to previous knowledge on the function of the amplified and over-expressed genes and on their implication in organophosphate insecticide resistance in other species allow to discard the possibility that this gene amplification spread by drift in the selected population.

In a second part of the paper, copy number variation for CCE genes is checked in field sample populations. This test reveals the presence of resistance alleles in half of the fourteen South East Asia populations sampled. Very interestingly, it also reveals a high level of complexity and diversity among the resistance alleles: it shows first the existence, both in the experimental and the field populations, of at least two amplified alleles (differing by the number of genes amplified) and second a high variation in the copy number of amplified genes. This indicates that gene amplification as a molecular resistance mechanism has actually lead to a high diversity of resistance alleles. These alleles are likely to differ both by the level of resistance conferred and the fitness cost imposed in the absence of the insecticide and these two values are affecting the evolution of their frequency in the field and ultimately the spread of resistance.

The last part of the paper is devoted to the development of a high-throughput Taqman assay which allows to determine rapidly the copy number of one of the esterase genes amplified in the resistance alleles described earlier. This assay is nicely validated and will definitely be a useful tool to determine the occurrence of these resistance alleles in field population. The fact that it gives access to the copy number will also allow to follow its copy number across time and get insight into the complexity of resistance evolution by gene amplification.

To sum up, this paper studies the implication of carboxy/choline esterase genes amplification in organophosphate resistance evolution in Ae. aegypti, reveals the diversity among individuals and populations of this resistance mechanism, because of variation both in the identity of the genes amplified and in their copy number and sets up a fast and efficient tool to detect and follow the spread of these resistant alleles in the field. Additionally, the different experimental approaches adopted have generated genomic and transcriptomic data, of which only the part related to CCE gene amplification has been exploited. These data are very likely to reveal other genomic and expression determinants of resistance that will give access to an extra degree of complexity in organophosphate insecticide resistance determinism and evolution.

References

Bass C, Field LM (2011) Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Management Science, 67, 886–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2189

Cattel J, Haberkorn C, Laporte F, Gaude T, Cumer T, Renaud J, Sutherland IW, Hertz JC, Bonneville J-M, Arnaud V, Nous C, Fustec B, Boyer S, Marcombe S, David J-P (2020) A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection. bioRxiv, 2020.06.08.139741, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139741

Moyes CL, Vontas J, Martins AJ, Ng LC, Koou SY, Dusfour I, Raghavendra K, Pinto J, Corbel V, David J-P, Weetman D (2017) Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11, e0005625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005625

| A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection | Julien Cattel, Chloé Haberkorn, Fréderic Laporte, Thierry Gaude, Tristan Cumer, Julien Renaud, Ian W. Sutherland, Jeffrey C. Hertz, Jean-Marc Bonneville, Victor Arnaud, Camille Noûs, Bénédicte Fustec, Sébastien Boyer, Sébastien Marcombe, Jean-Phil... | <p>By altering gene expression and creating paralogs, genomic amplifications represent a key component of short-term adaptive processes. In insects, the use of insecticides can select gene amplifications causing an increased expression of detoxifi... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | Stephanie Bedhomme | | 2020-06-09 13:27:18 | View |

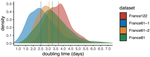

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France

Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in France

Recommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewers

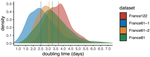

Sequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures.

Along with the three other reviewers of this manuscript, I was impressed with the careful and exhaustive phylodynamic analyses reported by Danesh et al. [3]. Notably, they take care to show that the major results are robust to the choice of priors and to sampling. The authors are also careful to note that the results are based on a limited sample size of SARS-Cov-2 genomes, which may not be representative of all regions in France. Their analysis also focused on the dominant SARS-Cov-2 lineage circulating in France, which is also circulating in other countries. The variations they inferred in epidemic growth in France could therefore be reflective on broader control policies in Europe, not only those in France. Clearly more work is needed to fully unravel which control policies (and where) were most effective in slowing the spread of SARS-Cov-2, but Danesh et al. [3] set a solid foundation to build upon with more data. Overall this is an exemplary study, enabled by rapid and open sharing of sequencing data, which provides a template to be replicated and expanded in other countries and regions as they deal with their own localized instances of this pandemic.

References

[1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2

[2] Fauver et al. (2020) Coast-to-Coast Spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the Early Epidemic in the United States. Cell, 181(5), 990-996.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.021

[3] Danesh, G., Elie, B., Michalakis, Y., Sofonea, M. T., Bal, A., Behillil, S., Destras, G., Boutolleau, D., Burrel, S., Marcelin, A.-G., Plantier, J.-C., Thibault, V., Simon-Loriere, E., van der Werf, S., Lina, B., Josset, L., Enouf, V. and Alizon, S. and the COVID SMIT PSL group (2020) Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemic in France. medRxiv, 2020.06.03.20119925, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

[4] Salje et al. (2020) Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-02548181

[5] Sofonea, M. T., Reyné, B., Elie, B., Djidjou-Demasse, R., Selinger, C., Michalakis, Y. and Samuel Alizon, S. (2020) Epidemiological monitoring and control perspectives: application of a parsimonious modelling framework to the COVID-19 dynamics in France. medRxiv, 2020.05.22.20110593. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.22.20110593

[6] Rambaut, A. (2020) Phylogenetic analysis of nCoV-2019 genomes. virological.org/t/phylodynamic-analysis-176-genomes-6-mar-2020/356

[7] Li et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med, 382: 1199-1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

| Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View |

Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic context

Recommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia.

Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009).

This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value.

References

Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15

Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414

Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5

Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108

Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y

Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536

| Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View |

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population

Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populations

Recommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1].

Recent technological advances made the generation of large-scale genomic data from temporal samples, either from experimental populations or historical or ancient samples, accessible to a wide scientific community [2]. Notably, temporal population genomic data allow for a direct observation and study of how, for instance, allele frequencies change through time in response to evolutionary stimuli. Such information can be exploited to detect loci under natural selection, either via mathematical modelling or by investigating empirical distributions [3].

However, most of current methods to detect selection from temporal genomic data have largely ignored selfing populations, despite the latter comprising a significant proportion of species with social and economic importance. Selfing changes genomic patterns by reducing the effective recombination rate, which makes distinguishing between neutral evolution and natural selection even more challenging than for the case of outcrossing populations [4]. Nevertheless, an outlier-approach based on temporal genomic data for the selfing Arabidopsis thaliana population revealed loci under selection [5].

This study suggested the promise of detecting selection for selfing populations and encouraged further investigations to test the power of selection scans under different mating systems.

To address this question, Navascués et al. [6] extended a previously proposed approach for temporal genome scan [7] to incorporate partial self-fertilization. In the original implementation [7], it is assumed that, under neutrality, all loci provide levels of genetic differentiation drawn from the same distribution. If some of the loci are under selection, such distribution should show heterogeneity. Navascués et al. [6] proposed a test for the homogeneity between loci-specific and genome-wide differentiation by deriving a null distribution of FST via simulations using SLiM [8]. After filtering for low-frequency variants and correct for multiple tests, authors derived a statistical test for selection and assess its power under a wide range of scenarios of selfing rate, selection coefficient, duration and type of selection [6].

The newly proposed test achieved good performance to distinguish between neutral and selected loci in most tested scenarios.

As expected, the test's performance significantly drops for scenarios of high selfing rates and selection from standing variation. Additionally, the probability to correctly detect selection decreases with increasing distance from the causal variant. Intriguingly, the test showed high power when the selected ancestral allele had an initial low frequency, and when the selected derived allele had a high initial frequency. When applied to a data set of around 1,000 SNPs from the highly selfing Medicago truncatula population, an annual plant of the legume family [9], the test did not provide any candidate loci under selection [6].

In summary, the detection of loci under selection in selfing populations is and largely remains a challenging task even when explictly account for the different mating system. However, recombination events that occurred before the selective pressure allow ancestral beneficial alleles to exhibit a detectable pattern of non-neutrality. As such, in partially selfing populations, the strength of the footprint of selection depends on several factors, mostly on the selfing rate, the time of onset and type of selection.

One major assumption of this study is that the model implies unstructured population and continuity between samples obtained from the same geographical location over time. As such assumptions are typically violated in real populations, further research into the effect of more complex demographic scenarios is desired to fully understand the power to detect selection in selfing populations. Furthermore, more power could be gained by including additional genomic information at each time point. In this context, recent approaches that make full use of genomic data based on deep learning [10] may contribute significantly towards this goal. Similarly, the effect of data filtering on the power to detect selection should be further explored, especially in the context of DNA resequencing experiments. These analyses will help elucidate the power offered by selection scans from temporal genomic data in selfing populations.

References

[1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14

[2] Leonardi M, Librado P, Der Sarkissian C, Schubert M, Alfarhan AH, Alquraishi SA, Al-Rasheid KAS, Gamba C, Willerslev E, Orlando L (2017) Evolutionary Patterns and Processes: Lessons from Ancient DNA. Systematic Biology, 66, e1–e29. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw059

[3] Dehasque M, Ávila‐Arcos MC, Díez‐del‐Molino D, Fumagalli M, Guschanski K, Lorenzen ED, Malaspinas A-S, Marques‐Bonet T, Martin MD, Murray GGR, Papadopulos AST, Therkildsen NO, Wegmann D, Dalén L, Foote AD (2020) Inference of natural selection from ancient DNA. Evolution Letters, 4, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.165

[4] Vitalis R, Couvet D (2001) Two-locus identity probabilities and identity disequilibrium in a partially selfing subdivided population. Genetics Research, 77, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300004833

[5] Frachon L, Libourel C, Villoutreix R, Carrère S, Glorieux C, Huard-Chauveau C, Navascués M, Gay L, Vitalis R, Baron E, Amsellem L, Bouchez O, Vidal M, Le Corre V, Roby D, Bergelson J, Roux F (2017) Intermediate degrees of synergistic pleiotropy drive adaptive evolution in ecological time. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 1, 1551–1561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0297-1

[6] Navascués M, Becheler A, Gay L, Ronfort J, Loridon K, Vitalis R (2020) Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population. bioRxiv, 2020.05.06.080895, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

[7] Goldringer I, Bataillon T (2004) On the Distribution of Temporal Variations in Allele Frequency: Consequences for the Estimation of Effective Population Size and the Detection of Loci Undergoing Selection. Genetics, 168, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.103.025908

[8] Messer PW (2013) SLiM: Simulating Evolution with Selection and Linkage. Genetics, 194, 1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.113.152181

[9] Siol M, Prosperi JM, Bonnin I, Ronfort J (2008) How multilocus genotypic pattern helps to understand the history of selfing populations: a case study in Medicago truncatula. Heredity, 100, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2008.5

[10] Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224

| Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View |

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Recommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms.

The phytopathogen nematode Meloidogyne incognita is one of the worst agricultural pests in warm climates (Savary et al. 2019). This species, as well as other root-knot nematodes (RKN), shows a wide geographical distribution range infecting diverse groups of plants. Although allopolyploidy may have played an important role on the wide adaptation of this phytopathogen, it may not explain by itself the rapid changes required to overcome plant resistance in a few generations. Paradoxically, M. incognita reproduces asexually via mitotic parthenogenesis (Trudgill and Blok 2001; Castagnone-Sereno and Danchin 2014) and only few single nucleotide variations were identified between different host races isolates (Koutsovoulos et al. 2020). Therefore, this is an interesting model to explore other sources of genomic variation such the TE activity and its role on the success and adaptability of this phytopathogen.

To address these questions, Kozlowski et al. (2020) estimated the TE mobility across 12 geographical isolates that presented phenotypic variations in Meloidogyne incognita, concluding that recent activity of TE in both genic and regulatory regions might have given rise to relevant functional differences between genomes. This was the first estimation of TE activity as a mechanism probably involved in genome plasticity of this root-knot nematode. This study also shed light on evolutionary mechanisms of asexual organisms with an allopolyploid origin. These authors re-annotated the 185 Mb triploid genome of M. incognita for TE content analysis using stringent filters (Kozlowski 2020a), and estimated activity by their distribution using a population genomics approach including isolates from different crops and locations. Canonical TE represented around 4.7% of the M. incognita genome of which mostly correspond to TIR (Terminal Inverted Repeats) and MITEs (Miniature Inverted repeat Transposable Elements) followed by Maverick DNA transposons and LTR (Long Terminal Repeats) retrotransposons. The result that most TE found were represented by DNA transposons is similar to the previous studies with the nematode species model Caenorhabditis elegans (Bessereau 2006; Kozlowski 2020b) and other nematodes as well. Canonical TE annotations were highly similar to their consensus sequences containing transposition machinery when TE are autonomous, whereas no genes involved in transposition were found in non-autonomous ones. These findings suggest recent activity of TE in the M. incognita genome. Other relevant result was the significant variation in TE presence frequencies found in more than 3,500 loci across isolates, following a bimodal distribution within isolates. However, variation in TE frequencies was low to moderate between isolates recapitulating the phylogenetic signal of isolates DNA sequences polymorphisms. A detailed analysis of TE frequencies across isolates allowed identifying polymorphic TE loci, some of which might be neo-insertions mostly of TIRs and MITEs (Kozlowski 2020c). Interestingly, the two thirds of the fixed neo-insertions were located in coding regions or in regulatory regions impacting expression of specific genes in M. incognita. Future research on proteomics is needed to evaluate the functional impact that these insertions have on adaptive evolution in M. incognita. In this line, this pioneer research of Kozlowski et al. (2020) is a first step that is also relevant to remark the role that allopolyploidy and reproduction have had on shaping nematode genomes.

References

[1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1

[2] Castagnone-Sereno P, Danchin EGJ. 2014. Parasitic success without sex - the nematode experience. J. Evol. Biol. 27:1323-1333. 10.1111/jeb.12337

[3] Faino L, Seidl MF, Shi-Kunne X, Pauper M, Berg GCM van den, Wittenberg AHJ, Thomma BPHJ. 2016. Transposons passively and actively contribute to evolution of the two-speed genome of a fungal pathogen. Genome Res. 26:1091-1100. 10.1101/gr.204974.116

[4] Glémin S, François CM, Galtier N. 2019. Genome Evolution in Outcrossing vs. Selfing vs. Asexual Species. In: Anisimova M, editor. Evolutionary Genomics: Statistical and Computational Methods. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Springer. p. 331-369. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9074-0_11

[5] Koutsovoulos GD, Marques E, Arguel M-J, Duret L, Machado ACZ, Carneiro RMDG, Kozlowski DK, Bailly-Bechet M, Castagnone-Sereno P, Albuquerque EVS, et al. 2020. Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple independent gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode pest. Evol. Appl. 13:442-457. 10.1111/eva.12881

[6] Kozlowski D. 2020a. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the M. incognita genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EPTDOS

[7] Kozlowski D. 2020b. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the C. elegans genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/LQCIW0

[8] Kozlowski D. 2020c. TE polymorphisms detection and analysis with PopoolationTE2. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EWJCT8

[9] Kozlowski DK, Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen R, Da Rocha M, Koutsovoulos GD, Bailly-Bechet M, Danchin EG (2020) Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. bioRxiv, 2020.04.30.069948, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. 10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

[10] Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. 2019. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3:430-439. 10.1038/s41559-018-0793-y

[11] Trudgill DL, Blok VC. 2001. Apomictic, polyphagous root-knot nematodes: exceptionally successful and damaging biotrophic root pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 39:53-77. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.39.1.53

| Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View |

based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers