Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Sep 2020

Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primatesRylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais https://doi.org/10.1101/445072Studying genetic antagonisms as drivers of genome evolutionRecommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Qi Zhou and 3 anonymous reviewersSex chromosomes are special in the genome because they are often highly differentiated over much of their lengths and marked by degenerative evolution of their gene content. Understanding why sex chromosomes differentiate requires deciphering the forces driving their recombination patterns. Suppression of recombination may be subject to selection, notably because of functional effects of locking together variation at different traits, as well as longer-term consequences of the inefficient purge of deleterious mutations, both of which may contribute to patterns of differentiation [1]. As an example, male and female functions may reveal intrinsic antagonisms over the optimal genotypes at certain genes or certain combinations of interacting genes. As a result, selection may favour the recruitment of rearrangements blocking recombination and maintaining the association of sex-antagonistic allele combinations with the sex-determining locus. References [1] Charlesworth D (2017) Evolution of recombination rates between sex chromosomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160456. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0456 | Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates | Rylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais | <p>Sex chromosomes are typically comprised of a non-recombining region and a recombining pseudoautosomal region. Accurately quantifying the relative size of these regions is critical for sex chromosome biology both from a functional (i.e. number o... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Mathieu Joron | 2019-02-04 15:16:32 | View | |

20 Dec 2016

POSTPRINT

Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective RegimesHuang Y, Agrawal AF 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336Genetic adaptation counters phenotypic plasticity in experimental evolutionRecommended by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Stephanie BedhommeHow do phenotypic plasticity and adaptive evolution interact in a novel or changing environment? Does evolution by natural selection generally reinforce initially plastic phenotypic responses, or does it instead oppose them? And to what extent does evolution of a trait involve evolution of its plasticity? These questions have lied at the heart of research on phenotypic evolution in heterogeneous environments ever since it was realized that the environment is likely to affect the expression of many (perhaps most) characters of an individual. Importantly, this broad definition of phenotypic plasticity as change in the average phenotype of a given genotype in response to its environment of development (or expression) does not involve any statement about the adaptiveness of the plastic changes. Theory on the evolution of plasticity has devoted much effort to understanding how reaction norm should evolve under different regimes of environmental change in space and time, and depending on genetic constraints on reaction norm shapes. However on an empirically ground, the questions above have mostly been addressed for individual traits, often chosen a priori for their likeliness to exhibit adaptive plasticity, and we still lack more systematic answers. These can be provided by so-called ‘phenomic’ approaches, where a large number of traits are tracked without prior information on their biological or ecological function. A problem is that the number of phenotypic characters that can be measured in an organism is virtually infinite (and to some extent arbitrary), and that scaling issues makes it difficult to compare different sets of traits. Gene-expression levels offer a partial solution to this dilemma, as they can be considered as a very large number of traits (one per typed gene) that can be measured easily and uniformly (fold change in the number of reads in RNAseq). As for any traits, expression levels of different genes may be genetically correlated, to an extent that depends on their regulation mechanism: cis-regulatory sequences that only affect expression of neighboring genes are likely to cause independent gene expression, while more systematic modifiers of expression (e.g. trans-regulators such as transcription factors) may cause correlated genetic responses of the expression of many genes. Huang and Agrawal [1] have studied plasticity and evolution of gene expression level in young larvae of populations of Drosophila melanogaster that have evolved for about 130 generations under either a constant environment (salt or cadmium), or an environment that is heterogeneous in time or space (combining salt and cadmium). They report a wealth of results, of which we summarize the most striking here. First, among genes that (i) were initially highly plastic and (ii) evolved significant divergence in expression levels between constant environment treatments, the evolved divergence is predominantly in the opposite direction to the initial plastic response. This suggests that either plasticity was initially maladaptive, or the selective pressure changed during the evolutionary process (see below). This somewhat unexpected result strikingly mirrors that from a study published last year in Nature [2], where the same pattern was found for responses of guppies to the presence of predators. However, Huang and Agrawal [1] went beyond this study by deciphering the underlying mechanisms in several interesting ways. First, they showed that change in gene expression often occurred at genes close to SNPs with differentiated frequencies across treatments (but not at genes with differentiated SNPs in their coding sequences), suggesting that cis-regulatory sequences are involved. This is also suggested by the fact that changes in gene expression are mostly caused by the increased expression of only one allele at polymorphic loci, and is a first step towards investigating the genetic underpinnings of (co)variation in gene expression levels. Another interesting set of findings concerns evolution of plasticity in treatments with variable environments. To compare the gene-expression plasticity that evolved in these treatments to an expectation, the authors considered that the expression levels in populations maintained for a long time under constant salt or cadmium had reached an optimum. The differences between these expression levels were thus assumed to predict the level of plasticity that should evolve in a heterogeneous environment (with both cadmium and salt) under perfect environmental predictability. The authors showed that plasticity did evolve more in the expected direction in heterogeneous than in constant environments, resulting in better adapted final expression levels across environments. Taken collectively, these results provide an unprecedented set of patterns that are greatly informative on how plasticity and evolution interact in constant versus changing environments. But of course, interpretations in terms of adaptive versus maladaptive plasticity are more challenging, as the authors themselves admit. Even though environmentally determined gene expression is the basic mechanism underlying the phenotypic plasticity of most traits, it is extremely difficult to relate to more integrated phenotypes for which we can understand the selection pressures, especially in multicellular organisms. The authors have recently investigated evolutionary change of quantitative traits in these selected lines, so it might be possible to establish links between reaction norms for macroscopic traits to those for gene expression levels. Such an approach would also involve tracking gene expression throughout life, rather than only in young larvae as done here, thus putting phenotypic complexity back in the picture also for expression levels. Another difficulty is that a plastic response that was originally adaptive may be replaced by an opposite evolutionary response in the long run, without having to invoke initially maladaptive plasticity. For instance, the authors mention the possibility that a generic stress response is initially triggered by cadmium, but is eventually unnecessary and costly after evolution of genetic mechanisms for cadmium detoxification (a case of so-called genetic accommodation). In any case, this study by Huang and Agrawal [1], together with the one by Ghalambor et al. last year [2], reports novel and unexpected results, which are likely to stimulate researchers interested in plasticity and evolution in heterogeneous environments for the years to come. References [1] Huang Y, Agrawal AF. 2016. Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes. PLoS Genetics 12:e1006336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006336 [2] Ghalambor CK, Hoke KL, Ruell EW, Fischer EK, Reznick DN, Hughes KA. 2015. Non-adaptive plasticity potentiates rapid adaptive evolution of gene expression in nature. Nature 525: 372-375. doi: 10.1038/nature15256 | Experimental Evolution of Gene Expression and Plasticity in Alternative Selective Regimes | Huang Y, Agrawal AF | Little is known of how gene expression and its plasticity evolves as populations adapt to different environmental regimes. Expression is expected to evolve adaptively in all populations but only those populations experiencing environmental heterog... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Expression Studies, Phenotypic Plasticity | Luis-Miguel Chevin | 2016-12-20 09:04:15 | View | |

20 Nov 2017

Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selectionDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze 10.1101/180000Understanding genetic variance, load, and inbreeding depression with selfingRecommended by Aneil F. Agrawal based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 1 anonymous reviewerA classic problem in evolutionary biology is to understand the genetic variance in fitness. The simplest hypothesis is that variation exists, even in well-adapted populations, as a result of the balance between mutational input and selective elimination. This variation causes a reduction in mean fitness, known as the mutation load. Though mutation load is difficult to quantify empirically, indirect evidence of segregating genetic variation in fitness is often readily obtained by comparing the fitness of inbred and outbred offspring, i.e., by measuring inbreeding depression. Mutation-selection balance models have been studied as a means of understanding the genetic variance in fitness, mutation load, and inbreeding depression. Since their inception, such models have increased in sophistication, allowing us to ask these questions under more realistic and varied scenarios. The new theoretical work by Abu Awad and Roze [1] is a substantial step forward in understanding how arbitrary levels of self-fertilization affect variation, load and inbreeding depression under mutation-selection balance. References [1] Abu Awad D and Roze D. 2017. Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection. bioRxiv, 180000, ver. 4 of 17th November 2017. doi: 10.1101/180000 [2] Lande R. 1977. The influence of the mating system on the maintenance of genetic variability in polygenic characters. Genetics 86: 485–498. [3] Charlesworth D and Charlesworth B. 1987. Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 237–268. doi: 10.1111/10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321 [4] Lande R and Porcher E. 2015. Maintenance of quantitative genetic variance under partial self-fertilization, with implications for the evolution of selfing. Genetics 200: 891–906. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176693 [5] Roze D. 2015. Effects of interference between selected loci on the mutation load, inbreeding depression, and heterosis. Genetics 201: 745–757. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.178533 [6] Martin G and Lenormand T. 2006. A general multivariate extension of Fisher's geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60: 893–907. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01169.x [7] Martin G, Elena SF and Lenormand T. 2007. Distributions of epistasis in microbes fit predictions from a fitness landscape model. Nature Genetics 39: 555–560. doi: 10.1038/ng1998 | Effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance, mutation load and inbreeding depression under stabilizing selection | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | The mating system of a species is expected to have important effects on its genetic diversity. In this paper, we explore the effects of partial selfing on the equilibrium genetic variance Vg, mutation load L and inbreeding depression δ under stabi... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Aneil F. Agrawal | 2017-08-26 09:29:20 | View | |

20 May 2020

How much does Ne vary among species?Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle https://doi.org/10.1101/861849Further questions on the meaning of effective population sizeRecommended by Martin Lascoux based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIn spite of its name, the effective population size, Ne, has a complex and often distant relationship to census population size, as we usually understand it. In truth, it is primarily an abstract concept aimed at measuring the amount of genetic drift occurring in a population at any given time. The standard way to model random genetic drift in population genetics is the Wright-Fisher model and, with a few exceptions, definitions of the effective population size stems from it: “a certain model has effective population size, Ne, if some characteristic of the model has the same value as the corresponding characteristic for the simple Wright-Fisher model whose actual size is Ne” (Ewens 2004). Since Sewall Wright introduced the concept of effective population size in 1931 (Wright 1931), it has flourished and there are today numerous definitions of it depending on the process being examined (genetic diversity, loss of alleles, efficacy of selection) and the characteristic of the model that is considered. These different definitions of the effective population size were generally introduced to address specific aspects of the evolutionary process. One aspect that has been hotly debated since the first estimates of genetic diversity in natural populations were published is the so-called Lewontin’s paradox (1974). Lewontin noted that the observed variation in heterozygosity across species was much smaller than one would expect from the neutral expectations calculated with the actual size of the species. References Brandvain Y, Wright SI (2016) The Limits of Natural Selection in a Nonequilibrium World. Trends in Genetics, 32, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.004 | How much does Ne vary among species? | Nicolas Galtier, Marjolaine Rousselle | <p>Genetic drift is an important evolutionary force of strength inversely proportional to *Ne*, the effective population size. The impact of drift on genome diversity and evolution is known to vary among species, but quantifying this effect is a d... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Martin Lascoux | 2019-12-08 00:11:00 | View | |

08 Aug 2018

Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutationsE. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David https://doi.org//273367Inbreeding compensates for reduced sexual selection in purging deleterious mutationsRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTwo evolutionary processes have been shown in theory to enhance the effects of natural selection in purging deleterious mutations from a population (here ""natural"" selection is defined as ""selection other than sexual selection""). First, inbreeding, especially self-fertilization, facilitates the removal of deleterious recessive alleles, the effects of which are largely hidden from selection in heterozygotes when mating is random. Second, sexual selection can facilitate the removal of deleterious alleles of arbitrary dominance, with little or no demographic cost, provided that deleterious effects are greater in males than in females (""genic capture""). Inbreeding (especially selfing) and sexual selection are often negatively correlated in nature. Empirical tests of the role of sexual selection in purging deleterious mutations have been inconsistent, potentially due to the positive relationship between sexual selection and intersexual genetic conflict. References [1] Noël, E., Fruitet, E., Lelaurin, D., Bonel, N., Segard, A., Sarda, V., Jarne, P., & David P. (2018). Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations. bioRxiv, 273367, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/273367 | Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations | E. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100055). Theory and empirical data showed that two processes can boost selection against deleterious mutations, ... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Baer | Anonymous | 2018-03-01 08:12:37 | View |

06 Apr 2021

How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans?Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030Be careful when studying selection based on polygenic score overdispersionRecommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lawrence Uricchio, Mashaal Sohail, Barbara Bitarello and 1 anonymous reviewer

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been a great promise for our understanding of the connection between genotype and phenotype. Today, the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog contains 251,401 associations from 4,961 studies (1). This wealth of studies has also generated interest to use the summary statistics beyond the few top hits in order to make predictions for individuals without known phenotype, e.g. to predict polygenic risk scores or to study polygenic selection by comparing different groups. For instance, polygenic selection acting on the most studied polygenic trait, height, has been subject to multiple studies during the past decade (e.g. 2–6). They detected north-south gradients in Europe which were consistent with expectations. However, their GWAS summary statistics were based on the GIANT consortium data set, a meta-analysis of GWAS conducted in different European cohorts (7,8). The availability of large data sets with less stratification such as the UK Biobank (9) has led to a re-evaluation of those results. The nature of the GIANT consortium data set was realized to represent a potential problem for studies of polygenic adaptation which led several of the authors of the original articles to caution against the interpretations of polygenic selection on height (10,11). This was a great example on how the scientific community assessed their own earlier results in a critical way as more data became available. At the same time it left the question whether there is detectable polygenic selection separating populations more open than ever. Generally, recent years have seen several articles critically assessing the portability of GWAS results and risk score predictions to other populations (12–14). Refoyo-Martínez et al. (15) are now presenting a systematic assessment on the robustness of cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans. They compiled GWAS results for complex traits which have been studied in more than one cohort and then use allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes Project data (16) set to detect signals of polygenic score overdispersion. As the source for the allele frequencies is kept the same across all tests, differences between the signals must be caused by the underlying GWAS. The results are concerning as the level of overdispersion largely depends on the choice of GWAS cohort. Cohorts with homogenous ancestries show little to no overdispersion compared to cohorts of mixed ancestries such as meta-analyses. It appears that the meta-analyses fail to fully account for stratification in their data sets. The authors based most of their analyses on the heavily studied trait height. Additionally, they use educational attainment (measured as the number of school years of an individual) as an example. This choice was due to the potential over- or misinterpretation of results by the media, the general public and by far right hate groups. Such traits are potentially confounded by unaccounted cultural and socio-economic factors. Showing that previous results about polygenic selection on educational attainment are not robust is an important result that needs to be communicated well. This forms a great example for everyone working in human genomics. We need to be aware that our results can sometimes be misinterpreted. And we need to make an effort to write our papers and communicate our results in a way that is honest about the limitations of our research and that prevents the misuse of our results by hate groups. This article represents an important contribution to the field. It is cruicial to be aware of potential methodological biases and technical artifacts. Future studies of polygenic adaptation need to be cautious with their interpretations of polygenic score overdispersion. A recommendation would be to use GWAS results obtained in homogenous cohorts. But even if different biobank-scale cohorts of homogeneous ancestry are employed, there will always be some remaining risk of unaccounted stratification. These conclusions may seem sobering but they are part of the scientific process. We need additional controls and new, different methods than polygenic score overdispersion for assessing polygenic selection. Last year also saw the presentation of a novel approach using sequence data and GWAS summary statistics to detect directional selection on a polygenic trait (17). This new method appears to be robust to bias stemming from stratification in the GWAS cohort as well as other confounding factors. Such new developments show light at the end of the tunnel for the use of GWAS summary statistics in the study of polygenic adaptation. References 1. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1005–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1120 2. Turchin MC, Chiang CW, Palmer CD, Sankararaman S, Reich D, Hirschhorn JN. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs. Nature Genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):1015–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2368 3. Berg JJ, Coop G. A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2014 Aug 7;10(8):e1004412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004412 4. Robinson MR, Hemani G, Medina-Gomez C, Mezzavilla M, Esko T, Shakhbazov K, et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nature Genetics. 2015 Nov;47(11):1357–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3401 5. Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015 Dec;528(7583):499–503. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152 6. Racimo F, Berg JJ, Pickrell JK. Detecting polygenic adaptation in admixture graphs. Genetics. 2018. Arp;208(4):1565–1584. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300489 7. Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7317):832–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09410 8. Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014 Nov;46(11):1173–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097 9. Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7726):203–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z 10. Berg JJ, Harpak A, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Joergensen AM, Mostafavi H, Field Y, et al. Reduced signal for polygenic adaptation of height in UK Biobank. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39725. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39725 11. Sohail M, Maier RM, Ganna A, Bloemendal A, Martin AR, Turchin MC, et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. eLife. 2019 Mar 21;8:e39702. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39702 12. Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics. 2019 Apr;51(4):584–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x 13. Bitarello BD, Mathieson I. Polygenic Scores for Height in Admixed Populations. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):4027–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401658 14. Uricchio LH, Kitano HC, Gusev A, Zaitlen NA. An evolutionary compass for detecting signals of polygenic selection and mutational bias. Evolution Letters. 2019;3(1):69–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.97 15. Refoyo-Martínez A, Liu S, Jørgensen AM, Jin X, Albrechtsen A, Martin AR, Racimo F. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? bioRxiv, 2021, 2020.07.13.200030, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200030 16. Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015 Sep 30;526(7571):68–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 17. Stern AJ, Speidel L, Zaitlen NA, Nielsen R. Disentangling selection on genetically correlated polygenic traits using whole-genome genealogies. bioRxiv. 2020 May 8;2020.05.07.083402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.083402 | How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? | Alba Refoyo-Martínez, Siyang Liu, Anja Moltke Jørgensen, Xin Jin, Anders Albrechtsen, Alicia R. Martin, Fernando Racimo | <p>Over the past decade, summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been used to detect and quantify polygenic adaptation in humans. Several studies have reported signatures of natural selection at sets of SNPs associated... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genetic conflicts, Human Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | 2020-08-14 15:06:54 | View | |

24 Oct 2019

Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspectiveEmmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1Phylogenetic approaches for reconstructing macroevolutionary scenarios of phytophagous insect diversificationRecommended by Hervé Sauquet based on reviews by Brian O'Meara and 1 anonymous reviewerPlant-animal interactions have long been identified as a major driving force in evolution. However, only in the last two decades have rigorous macroevolutionary studies of the topic been made possible, thanks to the increasing availability of densely sampled molecular phylogenies and the substantial development of comparative methods. In this extensive and thoughtful perspective [1], Jousselin and Elias thoroughly review current hypotheses, data, and available macroevolutionary methods to understand how plant-insect interactions may have shaped the diversification of phytophagous insects. First, the authors review three main hypotheses that have been proposed to lead to host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects: the ‘escape and radiate’, ‘oscillation’, and ‘musical chairs’ scenarios, each with their own set of predictions. Jousselin and Elias then synthesize a vast core of recent studies on different clades of insects, where explicit phylogenetic approaches have been used. In doing so, they highlight heterogeneity in both the methods being used and predictions being tested across these studies and warn against the risk of subjective interpretation of the results. Lastly, they advocate for standardization of phylogenetic approaches and propose a series of simple tests for the predictions of host-driven speciation scenarios, including the characterization of host-plant range history and host breadth history, and diversification rate analyses. This helpful review will likely become a new point of reference in the field and undoubtedly help many researchers formalize and frame questions of plant-insect diversification in future studies of phytophagous insects. References [1] Jousselin, E., Elias, M. (2019). Testing Host-Plant Driven Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: A Phylogenetic Perspective. arXiv, 1910.09510, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09510v1 | Testing host-plant driven speciation in phytophagous insects : a phylogenetic perspective | Emmanuelle Jousselin, Marianne Elias | During the last two decades, ecological speciation has been a major research theme in evolutionary biology. Ecological speciation occurs when reproductive isolation between populations evolves as a result of niche differentiation. Phytophagous ins... |  | Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Speciation, Species interactions | Hervé Sauquet | 2019-02-25 17:31:33 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

17 Feb 2020

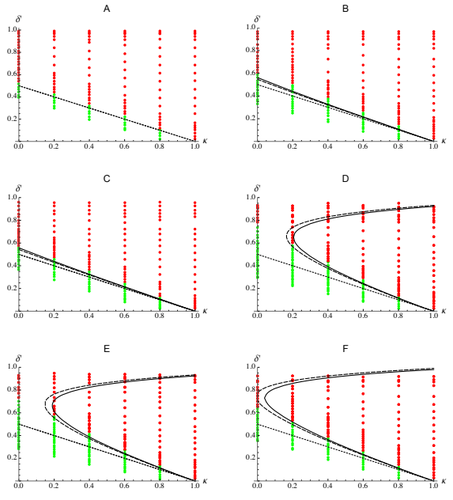

Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilizationDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/809814Epistasis and the evolution of selfingRecommended by Sylvain Gandon based on reviews by Nick Barton and 1 anonymous reviewerThe evolution of selfing results from a balance between multiple evolutionary forces. Selfing provides an "automatic advantage" due to the higher efficiency of selfers to transmit their genes via selfed and outcrossed offspring. Selfed offspring, however, may suffer from inbreeding depression. In principle the ultimate evolutionary outcome is easy to predict from the relative magnitude of these two evolutionary forces [1,2]. Yet, several studies explicitly taking into account the genetic architecture of inbreeding depression noted that these predictions are often too restrictive because selfing can evolve in a broader range of conditions [3,4]. References [1] Holsinger, K. E., Feldman, M. W., and Christiansen, F. B. (1984). The evolution of self-fertilization in plants: a population genetic model. The American Naturalist, 124(3), 446-453. doi: 10.1086/284287 | Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilization | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | <p>Inbreeding depression resulting from partially recessive deleterious alleles is thought to be the main genetic factor preventing self-fertilizing mutants from spreading in outcrossing hermaphroditic populations. However, deleterious alleles may... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Gandon | 2019-10-18 09:29:41 | View | |

30 May 2023

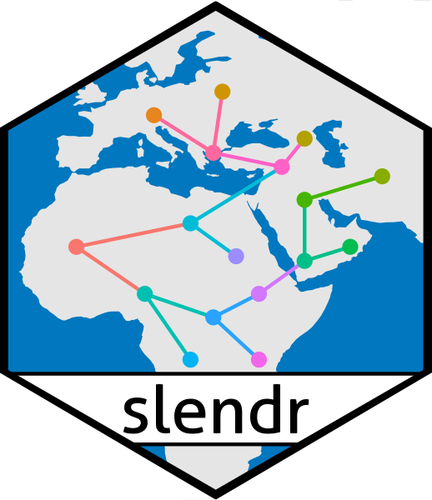

slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapesMartin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041A new powerful tool to easily encode the geo-spatial dimension in population genetics simulationsRecommended by Emiliano Trucchi based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Liisa Loog and 2 anonymous reviewers

Models explaining the evolutionary processes operating in living beings are often impossible to test in the real world. This is mainly because of the long time (i.e., the number of generations) which is necessary for evolution to unfold. In addition, any such experiment would require a large number of individuals and, more importantly, many replicates to account for the inherent variance of the evolutionary processes under investigation. Only organisms with fast generation times and favourable rearing conditions can be used to explicitly test for specific evolutionary hypotheses. Computer simulations have filled this gap, revolutionising experimental testing in evolutionary biology by integrating genetic models into complex population dynamics, which can be run for (potentially) any length of time. Without going into an extensive description of the many available approaches for population genetics simulations (an exhaustive review can be found in Hoban et al 2012), three main aspects are, in my opinion, important for categorising and choosing one simulation approach over another. The first concerns the basic distinction between coalescent-based and individual-based simulators: the former being an efficient approach, which simulates back in time the coalescence events of a sample of homologous DNA fragments, while the latter is a more computationally intensive approach where all of the individuals (and their underlying genetic/genomic features) in the population are simulated forward-in-time, generation after generation. The second aspect concerns the simulation of natural selection. Although natural selection can be integrated into backward-in-time simulations, it is more realistically implemented as individual-based fitness in forward-in-time simulators. The third point, which has been often overlooked in evolutionary simulations, is about the possibility to design a simulation scenario where individuals and populations can exploit a physical (geographical) space. Amongst the coalescent-based simulators, SPLATCHE (Currat et al 2004), and its derivatives, is one of the few simulation tools deploying the coalescence process in sub-demes which are all connected by migration, thus getting as close as possible to a spatially-explicit population. On the other hand, individual-based simulators, whose development followed the increasing power of computational machines, offer a great opportunity to include spatio-temporal dynamics within a genomic simulation model. One of the most realistic and efficient individual-based forward-in-time simulators available is SLiM (Haller and Messer 2017), which allows users to implement simulations in arbitrarily complex spaces. Here, the more challenging part is encoding the spatially-explicit scenarios using the SLiM-specific EIDOS language. The new R package slendr (Petr et al 2022) offers a practical solution to this issue. By wrapping different tools into a well-known scripting language, slendr allows the design of spatiotemporal simulation scenarios which can be directly executed in the individual-based SLiM simulator, and the output stored with modern tree-sequence analysis tools (tskit; Kellerer et al 2018). Alternatively, simulations of non-spatial models can be run using a coalescent-based algorithm (msprime; Baumdicker et al 2022). The main advantage of slendr is that the whole simulative experiment can be performed entirely in the R environment, taking advantage of the many libraries available for geospatial and genomic data analysis, statistics, and visualisation. The open-source nature of this package, whose main aim is to make complex population genomics modelling more accessible, and the vibrant community of SLiM and tskit users will very likely make slendr widely used amongst the molecular ecology and evolutionary biology communities. Slendr handles real Earth cartographic data where users can design realistic demographic processes which characterise natural populations (i.e., expansions, displacement of large populations, interactions among populations, migrations, population splits, etc.) by changing spatial population boundaries across time and space. All in all, slendr is a very flexible and scalable framework to test the accuracy of spatial models, hypotheses about demography and selection, and interactions between organisms across space and time. REFERENCES Baumdicker, F., Bisschop, G., Goldstein, D., Gower, G., Ragsdale, A. P., Tsambos, G., ... & Kelleher, J. (2022). Efficient ancestry and mutation simulation with msprime 1.0. Genetics, 220(3), iyab229. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab229 Currat, M., Ray, N., & Excoffier, L. (2004). SPLATCHE: a program to simulate genetic diversity taking into account environmental heterogeneity. Molecular Ecology Notes, 4(1), 139-142. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00582.x Haller, B. C., & Messer, P. W. (2017). SLiM 2: flexible, interactive forward genetic simulations. Molecular biology and evolution, 34(1), 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw211 Hoban, S., Bertorelle, G., & Gaggiotti, O. E. (2012). Computer simulations: tools for population and evolutionary genetics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(2), 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3130 Kelleher, J., Thornton, K. R., Ashander, J., & Ralph, P. L. (2018). Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS computational biology, 14(11), e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Petr, M., Haller, B. C., Ralph, P. L., & Racimo, F. (2023). slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2022.03.20.485041, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.20.485041 | slendr: a framework for spatio-temporal population genomic simulations on geographic landscapes | Martin Petr, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, Fernando Racimo | <p style="text-align: justify;">One of the goals of population genetics is to understand how evolutionary forces shape patterns of genetic variation over time. However, because populations evolve across both time and space, most evolutionary proce... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emiliano Trucchi | 2022-09-14 12:57:56 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer

, where Ne is the effective population size and

, where Ne is the effective population size and  is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common

is the mean fitness effect of non-synonymous mutations. Assuming further that distinct species share a common DFE and therefore a common  . Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.

. Applying their newly developed approach to various datasets they conclude that the power of drift varies by a factor of at least 500 between large-Ne (Drosophila) and small-Ne species (H. sapiens). This is an order of magnitude larger than what would be obtained by comparing estimates of the variation in neutral diversity. Hence the proposed approach seems to have gone some way in making Lewontin’s paradox less paradoxical. But, perhaps more importantly, as the authors tersely point out at the end of the abstract their results further questions the meaning of Ne parameters in population genetics. And arguably this could well be the most important contribution of their study and something that is badly needed.