Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Jun 2021

Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic driftLaurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230Separating adaptation from drift: A cautionary tale from a self-fertilizing plantRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Pierre Olivier Cheptou, Jon Agren and Stefan LaurentIn recent years many studies have documented shifts in phenology in response to climate change, be it in arrival times in migrating birds, budset in trees, adult emergence in butterflies, or flowering time in annual plants (Coen et al. 2018; Piao et al. 2019). While these changes are, in part, explained by phenotypic plasticity, more and more studies find that they involve also genetic changes, that is, they involve evolutionary change (e.g., Metz et al. 2020). Yet, evolutionary change may occur through genetic drift as well as selection. Therefore, in order to demonstrate adaptive evolutionary change in response to climate change, drift has to be excluded as an alternative explanation (Hansen et al. 2012). A new study by Gay et al. (2021) shows just how difficult this can be. The authors investigated a recent evolutionary shift in flowering time by in a population an annual plant that reproduces predominantly by self-fertilization. The population has recently been subjected to increased temperatures and reduced rainfalls both of which are believed to select for earlier flowering times. They used a “resurrection” approach (Orsini et al. 2013; Weider et al. 2018): Genotypes from the past (resurrected from seeds) were compared alongside more recent genotypes (from more recently collected seeds) under identical conditions in the greenhouse. Using an experimental design that replicated genotypes, eliminated maternal effects, and controlled for microenvironmental variation, they found said genetic change in flowering times: Genotypes obtained from recently collected seeds flowered significantly (about 2 days) earlier than those obtained 22 generations before. However, neutral markers (microsatellites) also showed strong changes in allele frequencies across the 22 generations, suggesting that effective population size, Ne, was low (i.e., genetic drift was strong), which is typical for highly self-fertilizing populations. In addition, several multilocus genotypes were present at high frequencies and persisted over the 22 generations, almost as in clonal populations (e.g., Schaffner et al. 2019). The challenge was thus to evaluate whether the observed evolutionary change was the result of an adaptive response to selection or may be explained by drift alone. Here, Gay et al. (2021) took a particularly careful and thorough approach. First, they carried out a selection gradient analysis, finding that earlier-flowering plants produced more seeds than later-flowering plants. This suggests that, under greenhouse conditions, there was indeed selection for earlier flowering times. Second, investigating other populations from the same region (all populations are located on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, France), they found that a concurrent shift to earlier flowering times occurred also in these populations. Under the hypothesis that the populations can be regarded as independent replicates of the evolutionary process, the observation of concurrent shifts rules out genetic drift (under drift, the direction of change is expected to be random). The study may well have stopped here, concluding that there is good evidence for an adaptive response to selection for earlier flowering times in these self-fertilizing plants, at least under the hypothesis that selection gradients estimated in the greenhouse are relevant to field conditions. However, the authors went one step further. They used the change in the frequencies of the multilocus genotypes across the 22 generations as an estimate of realized fitness in the field and compared them to the phenotypic assays from the greenhouse. The results showed a tendency for high-fitness genotypes (positive frequency changes) to flower earlier and to produce more seeds than low-fitness genotypes. However, a simulation model showed that the observed correlations could be explained by drift alone, as long as Ne is lower than ca. 150 individuals. The findings were thus consistent with an adaptive evolutionary change in response to selection, but drift could only be excluded as the sole explanation if the effective population size was large enough. The study did provide two estimates of Ne (19 and 136 individuals, based on individual microsatellite loci or multilocus genotypes, respectively), but both are problematic. First, frequency changes over time may be influenced by the presence of a seed bank or by immigration from a genetically dissimilar population, which may lead to an underestimation of Ne (Wang and Whitlock 2003). Indeed, the low effective size inferred from the allele frequency changes at microsatellite loci appears to be inconsistent with levels of genetic diversity found in the population. Moreover, high self-fertilization reduces effective recombination and therefore leads to non-independence among loci. This lowers the precision of the Ne estimates (due to a higher sampling variance) and may also violate the assumption of neutrality due to the possibility of selection (e.g., due to inbreeding depression) at linked loci, which may be anywhere in the genome in case of high degrees of self-fertilization. There is thus no definite answer to the question of whether or not the observed changes in flowering time in this population were driven by selection. The study sets high standards for other, similar ones, in terms of thoroughness of the analyses and care in interpreting the findings. It also serves as a very instructive reminder to carefully check the assumptions when estimating neutral expectations, especially when working on species with complicated demographies or non-standard life cycles. Indeed the issues encountered here, in particular the difficulty of establishing neutral expectations in species with low effective recombination, may apply to many other species, including partially or fully asexual ones (Hartfield 2016). Furthermore, they may not be limited to estimating Ne but may also apply, for instance, to the establishment of neutral baselines for outlier analyses in genome scans (see e.g, Orsini et al. 2012). References Cohen JM, Lajeunesse MJ, Rohr JR (2018) A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 8, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0067-3 Gay L, Dhinaut J, Jullien M, Vitalis R, Navascués M, Ranwez V, Ronfort J (2021) Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift. bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.261230, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230 Hansen MM, Olivieri I, Waller DM, Nielsen EE (2012) Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Molecular Ecology, 21, 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05463.x Hartfield M (2016) Evolutionary genetic consequences of facultative sex and outcrossing. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 29, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12770 Metz J, Lampei C, Bäumler L, Bocherens H, Dittberner H, Henneberg L, Meaux J de, Tielbörger K (2020) Rapid adaptive evolution to drought in a subset of plant traits in a large-scale climate change experiment. Ecology Letters, 23, 1643–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13596 Orsini L, Schwenk K, De Meester L, Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Weider LJ (2013) The evolutionary time machine: using dormant propagules to forecast how populations can adapt to changing environments. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.009 Orsini L, Spanier KI, Meester LD (2012) Genomic signature of natural and anthropogenic stress in wild populations of the waterflea Daphnia magna: validation in space, time and experimental evolution. Molecular Ecology, 21, 2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05429.x Piao S, Liu Q, Chen A, Janssens IA, Fu Y, Dai J, Liu L, Lian X, Shen M, Zhu X (2019) Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Global Change Biology, 25, 1922–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14619 Schaffner LR, Govaert L, De Meester L, Ellner SP, Fairchild E, Miner BE, Rudstam LG, Spaak P, Hairston NG (2019) Consumer-resource dynamics is an eco-evolutionary process in a natural plankton community. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0960-9 Wang J, Whitlock MC (2003) Estimating Effective Population Size and Migration Rates From Genetic Samples Over Space and Time. Genetics, 163, 429–446. PMID: 12586728 Weider LJ, Jeyasingh PD, Frisch D (2018) Evolutionary aspects of resurrection ecology: Progress, scope, and applications—An overview. Evolutionary Applications, 11, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12563 | Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift | Laurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resurrection studies are a useful tool to measure how phenotypic traits have changed in populations through time. If these traits modifications correlate with the environmental changes that occurred during the time ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2020-08-21 17:26:59 | View | ||

31 Mar 2022

Gene network robustness as a multivariate characterArnaud Le Rouzic https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564Genetic and environmental robustness are distinct yet correlated evolvable traits in a gene networkRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert

Organisms often show robustness to genetic or environmental perturbations. Whether these two components of robustness can evolve separately is the focus of the paper by Le Rouzic [1]. Using theoretical analysis and individual-based computer simulations of a gene regulatory network model, he shows that multiple aspects of robustness can be investigated as a set of pleiotropically linked quantitative traits. While genetically correlated, various robustness components (e.g., mutational, developmental, homeostasis) of gene expression in the regulatory network evolved more or less independently from each other under directional selection. The quantitative approach of Le Rouzic could explain both how unselected robustness components can respond to selection on other components and why various robustness-related features seem to have their own evolutionary history. Moreover, he shows that all components were evolvable, but not all to the same extent. Robustness to environmental disturbances and gene expression stability showed the largest responses while increased robustness to genetic disturbances was slower. Interestingly, all components were positively correlated and remained so after selection for increased or decreased robustness. This study is an important contribution to the discussion of the evolution of robustness in biological systems. While it has long been recognized that organisms possess the ability to buffer genetic and environmental perturbations to maintain homeostasis (e.g., canalization [2]), the genetic basis and evolutionary routes to robustness and canalization are still not well understood. Models of regulatory gene networks have often been used to address aspects of robustness evolution (e.g., [3]). Le Rouzic [1] used a gene regulatory network model derived from Wagner’s model [4]. The model has as end product the expression level of a set of genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors). The level and stability of expression are a property of the regulatory interactions in the network. Le Rouzic made an important contribution to the study of such gene regulation models by using a quantitative genetics approach to the evolution of robustness. He crafted a way to assess the mutational variability and selection response of the components of robustness he was interested in. Le Rouzic’s approach opens avenues to investigate further aspects of gene network evolutionary properties, for instance to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Le Rouzic also discusses ways to measure his different robustness components in empirical studies. As the model is about gene expression levels at a set of protein-coding genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements, it naturally points to the possibility of using RNA sequencing to measure the variation of gene expression in know gene networks and assess their robustness. Robustness could then be studied as a multidimensional quantitative trait in an experimental setting. References [1] Le Rouzic, A (2022) Gene network robustness as a multivariate character. arXiv: 2101.01564, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564 [2] Waddington CH (1942) Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/150563a0 [3] Draghi J, Whitlock M (2015) Robustness to noise in gene expression evolves despite epistatic constraints in a model of gene networks. Evolution, 69, 2345–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12732 [4] Wagner A (1994) Evolution of gene networks by gene duplications: a mathematical model and its implications on genome organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 4387–4391. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.10.4387 | Gene network robustness as a multivariate character | Arnaud Le Rouzic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Robustness to genetic or environmental disturbances is often considered as a key property of living systems. Yet, in spite of being discussed since the 1950s, how robustness emerges from the complexity of genetic ar... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | Charles Mullon, Charles Rocabert, Diogo Melo | 2021-01-11 17:48:20 | View |

22 May 2023

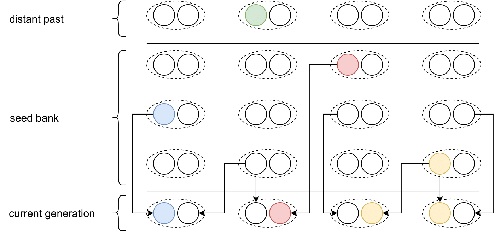

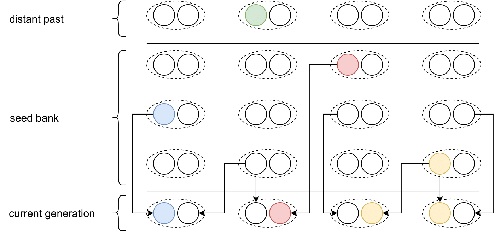

Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweepsKevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499New insights into the dynamics of selective sweeps in seed-banked speciesRecommended by Renaud Vitalis based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard based on reviews by Guillaume Achaz, Jere Koskela, William Shoemaker and Simon Boitard

Many organisms across the Tree of life have the ability to produce seeds, eggs, cysts, or spores, that can remain dormant for several generations before hatching. This widespread adaptive trait in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, has a significant impact on the ecology, population dynamics and population genetics of species that express it (Evans and Dennehy 2005). In population genetics, and despite the recognition of its evolutionary importance in many empirical studies, few theoretical models have been developed to characterize the evolutionary consequences of this trait on the level and distribution of neutral genetic diversity (see, e.g., Kaj et al. 2001; Vitalis et al. 2004), and also on the dynamics of selected alleles (see, e.g., Živković and Tellier 2018). However, due to the complexity of the interactions between evolutionary forces in the presence of dormancy, the fate of selected mutations in their genomic environment is not yet fully understood, even from the most recently developed models. In a comprehensive article, Korfmann et al. (2023) aim to fill this gap by investigating the effect of germ banking on the probability of (and time to) fixation of beneficial mutations, as well as on the shape of the selective sweep in their vicinity. To this end, Korfmann et al. (2023) developed and released their own forward-in-time simulator of genome-wide data, including neutral and selected polymorphisms, that makes use of Kelleher et al.’s (2018) tree sequence toolkit to keep track of gene genealogies. The originality of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) study is to provide new quantitative results for the effect of dormancy on the time to fixation of positively selected mutations, the shape of the genomic landscape in the vicinity of these mutations, and the temporal dynamics of selective sweeps. Their major finding is the prediction that germ banking creates narrower signatures of sweeps around positively selected sites, which are detectable for increased periods of time (as compared to a standard Wright-Fisher population). The availability of Korfmann et al.’s (2023) code will allow a wider range of parameter values to be explored, to extend their results to the particularities of the biology of many species. However, as they chose to extend the haploid coalescent model of Kaj et al. (2001), further development is needed to confirm the robustness of their results with a more realistic diploid model of seed dormancy. REFERENCES Evans, M. E. K., and J. J. Dennehy (2005) Germ banking: bet-hedging and variable release from egg and seed dormancy. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4): 431-451. https://doi.org/10.1086/498282 Kaj, I., S. Krone, and M. Lascoux (2001) Coalescent theory for seed bank models. Journal of Applied Probability, 38(2): 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1239/jap/996986745 Kelleher, J., K. R. Thornton, J. Ashander, and P. L. Ralph (2018) Efficient pedigree recording for fast population genetics simulation. PLoS Computational Biology, 14(11): e1006581. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006581 Korfmann, K., D. Abu Awad, and A. Tellier (2023) Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.26.489499 Vitalis, R., S. Glémin, and I. Olivieri (2004) When genes go to sleep: the population genetic consequences of seed dormancy and monocarpic perenniality. American Naturalist, 163(2): 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/381041 Živković, D., and A. Tellier (2018). All but sleeping? Consequences of soil seed banks on neutral and selective diversity in plant species. Mathematical Modelling in Plant Biology, 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99070-5_10 | Weak seed banks influence the signature and detectability of selective sweeps | Kevin Korfmann, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Seed banking (or dormancy) is a widespread bet-hedging strategy, generating a form of population overlap, which decreases the magnitude of genetic drift. The methodological complexity of integrating this trait impli... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Renaud Vitalis | 2022-05-23 13:01:57 | View | |

30 Mar 2023

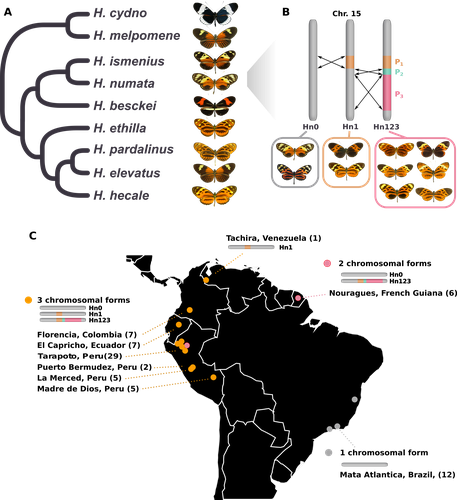

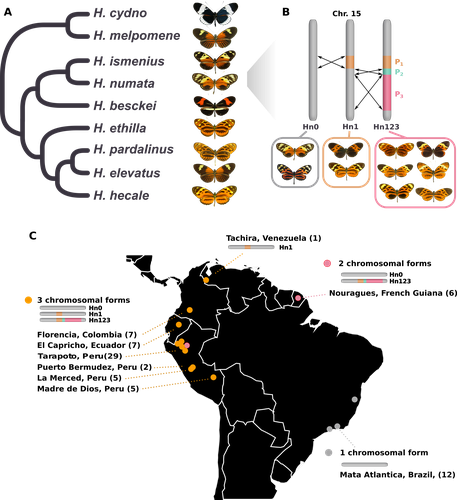

Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterflyMaría Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, Mathieu Joron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348Is genetic diversity enhanced by a supergene?Recommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Christelle Fraïsse and 2 anonymous reviewersThe butterfly species Heliconius numata has a remarkable wing pattern polymorphism, with multiple pattern morphs all controlled by a single genetic locus, which harbours multiple inversions. Each morph is a near-perfect mimic of a species in the fairly distantly related genus of butterflies, Melinaea. The article by Rodríguez de Cara et al (2023) argues that the balanced polymorphism at this single wing patterning locus actually has a major effect on genetic diversity across the whole genome. First, polymorphic populations within H. numata are more dioverse than those without polymorphism. Second, H. numata is more genetically diverse than other related species and finally reconstruction of historical demography suggests that there has been a recent increase in effective population size, putatively associated with the acquisition of the supergene polymorphism. The supergene itself generates disassortative mating, such that morphs prefer to mate with others dissimilar to themselves - in this way it is similar to mechanisms for preventing inbreeding such as self-incompatibility loci in plants. This provides a potential mechanism whereby non-random mating patterns could increase effective population size. The authors also explore this mechanism using forward simulations, and show that mating patterns at a single locus can influence linked genetic diversity over a large scale. Overall, this is an intriguing study, which suggests a far more widespread genetic impact of a single locus than might be expected. There are interesting parallels with mechanisms of inbreeding prevention in plants, such as the Pin/Thrum polymorphism in Primula, which also rely on mating patterns determined by a single locus but presumably also influence genetic diversity genome-wide by promoting outbreeding. REFERENCES Rodríguez de Cara MÁ, Jay P, Rougemont Q, Chouteau M, Whibley A, Huber B, Piron-Prunier F, Ramos RR, Freitas AVL, Salazar C, Silva-Brandão KL, Torres TT, Joron M (2023) Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow. bioRxiv, 2021.09.29.462348, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.29.462348 | Balancing selection at a wing pattern locus is associated with major shifts in genome-wide patterns of diversity and gene flow in a butterfly | María Ángeles Rodríguez de Cara, Paul Jay, Quentin Rougemont, Mathieu Chouteau, Annabel Whibley, Barbara Huber, Florence Piron-Prunier, Renato Rogner Ramos, André V. L. Freitas, Camilo Salazar, Karina Lucas Silva-Brandão, Tatiana Texeira Torres, M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Selection shapes genetic diversity around target mutations, yet little is known about how selection on specific loci affects the genetic trajectories of populations, including their genomewide patterns of diversity ... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Chris Jiggins | 2021-10-13 17:54:33 | View | |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

02 Nov 2022

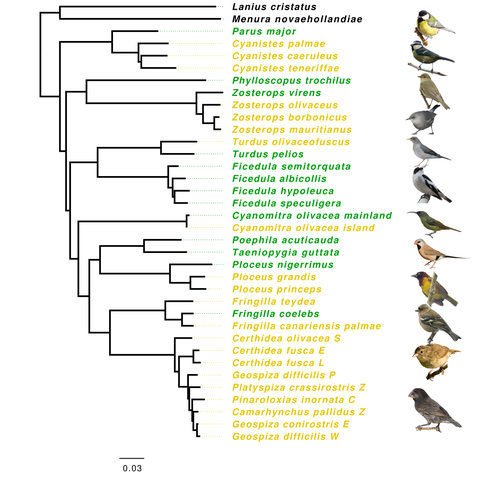

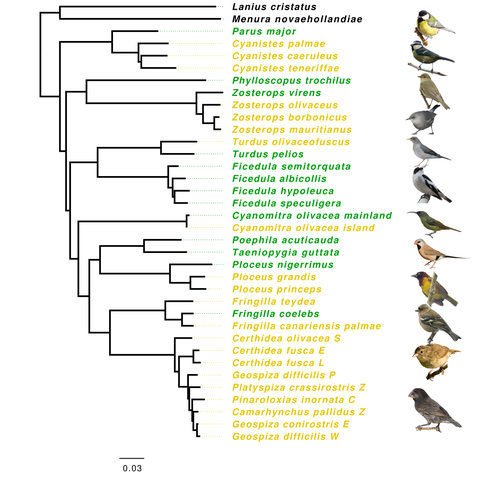

Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndromeMathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450Demographic effects may affect adaptation to islandsRecommended by Emma Berdan based on reviews by Steven Fiddaman and 3 anonymous reviewersThe unique challenges associated with living on an island often result in organisms displaying a specific suite of traits commonly referred to as “island syndrome” (Adler and Levins, 1994; Burns, 2019; Baeckens and Van Damme, 2020). Large phenotypic shifts such as changes in size (e.g. shifts to gigantism or dwarfism, Lomolino, 2005) or coloration (Doutrelant et al., 2016) abound in the literature. However, less obvious phenotypes may also play a key role in adaptation to islands. One such trait, reduced immune function, has important implications for the future of island populations in the face of anthropogenic-induced changes. Due to lower parasite pressure caused by a less diverse and less virulent parasite population, island hosts may show a decrease in immune defenses (Beadell et al., 2006; Pérez‐Rodríguez et al., 2013). However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as many studies have found ambiguous or conflicting results (Matson, 2006; Illera et al., 2015). While most previous work has examined various immunological parameters (e.g., antibody concentrations), here, Barthe et al. (2022) take the novel approach of examining molecular signatures of immune genes. Using comparative genomic data from 34 different species of birds the authors examine the ratio of synonymous substitutions (i.e., not changing an amino acid) to non-synonymous substitutions (i.e., changing an amino acid) in innate and acquired immune genes (Pn/Ps ratio). Because population sizes on islands are lower which will affect molecular evolution, they compare these results to data from 97 control genes. Assuming relaxed selection on islands predicts that the difference between the Pn/Ps ratio of immune genes and of control genes (ΔPn/Ps) is greater in island species compared to mainland ones. As with previous work the authors found that the results differ depending on the category of immune genes. Both forms of innate defense: beta-defensins and Toll-like receptors did not show higher ΔPn/Ps for island populations. As these genes still have a higher Pn/Ps than control genes, the authors argue these results are in line with these genes being under purifying selection but lacking an “island effect”. Instead, the authors argue that demographic effects (i.e., reductions in Ne) may lead to the decreased immunity documented in other studies. In contrast, there was a reduction in Pn/Ps in MHC II genes, known to be under balancing selection. This reduction was stronger in island species and thus the authors argue that this is the only class of genes where a role for relaxed selection can be invoked. Together these results demonstrate that the changes in immunity experienced by island species are complex and that different categories of immune genes can experience different selective pressures. By including control genes in their study, they particularly highlight the importance of accounting for shifts in Ne when examining patterns of island species evolution. Hopefully, this kind of framework will be applied to other taxa to determine if these results are widespread or more specific to birds. References Adler GH, Levins R (1994) The Island Syndrome in Rodent Populations. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 69, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1086/418744 Baeckens S, Van Damme R (2020) The island syndrome. Current Biology, 30, R338–R339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.029 Barthe M, Doutrelant C, Covas R, Melo M, Illera JC, Tilak M-K, Colombier C, Leroy T, Loiseau C, Nabholz B (2022) Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome. bioRxiv, 2021.11.21.469450, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.21.469450 Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Graves GR, Jhala YV, Peirce MA, Rahmani AR, Fonseca DM, Fleischer RC (2006) Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2935–2944. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3671 Burns KC (2019) Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379953 Doutrelant C, Paquet M, Renoult JP, Grégoire A, Crochet P-A, Covas R (2016) Worldwide patterns of bird colouration on islands. Ecology Letters, 19, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12588 Illera JC, Fernández-Álvarez Á, Hernández-Flores CN, Foronda P (2015) Unforeseen biogeographical patterns in a multiple parasite system in Macaronesia. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1858–1870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12548 Lomolino MV (2005) Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01314.x Matson KD (2006) Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 Pérez-Rodríguez A, Ramírez Á, Richardson DS, Pérez-Tris J (2013) Evolution of parasite island syndromes without long-term host population isolation: parasite dynamics in Macaronesian blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 22, 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12084 | Evolution of immune genes in island birds: reduction in population sizes can explain island syndrome | Mathilde BARTHE, Claire DOUTRELANT, Rita COVAS, Martim MELO, Juan Carlos ILLERA, Marie-Ka TILAK, Constance COLOMBIER, Thibault LEROY , Claire LOISEAU , Benoit NABHOLZ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Shared ecological conditions encountered by species that colonize islands often lead to the evolution of convergent phenotypes, commonly referred to as “island syndrome”. Reduced immune functions have been previousl... |  | Adaptation, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Emma Berdan | 2021-11-28 11:01:31 | View | |

25 Jan 2023

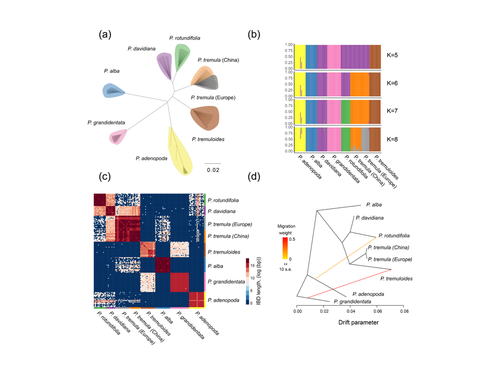

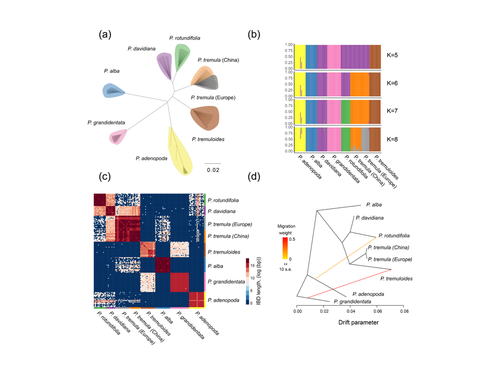

Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradientHuiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771Shedding light on genomic divergence along the speciation continuumRecommended by Violaine Llaurens based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Camille Roux, Steven van Belleghem and 1 anonymous reviewer

The article “Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient” by Shang et al. describes an amazing dataset where genomic variations among 21 pairs of diverging poplar species are compared. Such comparisons are still quite rare and are needed to shed light on the processes shaping genomic divergence along the speciation gradient. Relying on two hundred whole-genome resequenced samples from 8 species that diverged from 1.3 to 4.8 million years ago, the authors aim at identifying the key factors involved in the genomic differentiation between species. They carried out a wide range of robust statistical tests aiming at characterizing the genomic differentiation along the genome of these species pairs. They highlight in particular the role of linked selection and gene flow in shaping the divergence along the genomes of species pairs. They also confirm the significance of introgression among species with a net divergence larger than the upper boundaries of the grey zone of speciation previously documented in animals (da from 0.005 to 0.02, Roux et al. 2016). Because these findings pave the way to research about the genomic mechanisms associated with speciation in species with allopatric and parapatric distributions, I warmingly recommend this article. References Roux C, Fraïsse C, Romiguier J, Anciaux Y, Galtier N, Bierne N (2016) Shedding Light on the Grey Zone of Speciation along a Continuum of Genomic Divergence. PLOS Biology, 14, e2000234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234 Shang H, Rendón-Anaya M, Paun O, Field DL, Hess J, Vogl C, Liu J, Ingvarsson PK, Lexer C, Leroy T (2023) Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient. bioRxiv, 2021.08.26.457771, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.26.457771 | Drivers of genomic landscapes of differentiation across Populus divergence gradient | Huiying Shang, Martha Rendón-Anaya, Ovidiu Paun, View David L Field, Jaqueline Hess, Claus Vogl, Jianquan Liu, Pär K. Ingvarsson, Christian Lexer, Thibault Leroy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Speciation, the continuous process by which new species form, is often investigated by looking at the variation of nucleotide diversity and differentiation across the genome (hereafter genomic landscapes). A key cha... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Violaine Llaurens | 2021-09-06 14:12:27 | View | |

02 Feb 2023

Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibilityKatherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663Susceptibility to infection is not explained by sex or differences in tissue tropism across different species of DrosophilaRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Greg Hurst and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding factors explaining both intra and interspecific variation in susceptibility to infection by parasites remains a key question in evolutionary biology. Within a species variation in susceptibility is often explained by differences in behaviour affecting exposure to infection and/or resistance affecting the degree by which parasite growth is controlled (Roy & Kirchner, 2000, Behringer et al., 2000). This can vary between the sexes (Kelly et al., 2018) and may be explained by the ability of a parasite to attack different organs or tissues (Brierley et al., 2019). However, what goes on within one species is not always relevant to another, making it unclear when patterns can be scaled up and generalised across species. This is also important to understand when parasites may jump hosts, or identify species that may be susceptible to a host jump (Longdon et al., 2015). Phylogenetic distance between hosts is often an important factor explaining susceptibility to a particular parasite in plant and animal hosts (Gilbert & Webb, 2007, Faria et al., 2013). In two separate experiments, Roberts and Longdon (Roberts & Longdon, 2022) investigated how sex and tissue tropism affected variation in the load of Drosophila C Virus (DCV) across multiple Drosophila species. DCV load has been shown to correlate positively with mortality (Longdon et al., 2015). Overall, they found that load did not vary between the sexes; within a species males and females had similar DCV loads for 31 different species. There was some variation in levels of DCV growth in different tissue types, but these too were consistent across males for 7 species of Drosophila. Instead, in both experiments, host phylogeny or interspecific variation, explained differences in DCV load with some species being more infected than others. This study is neat in that it incorporates and explores simultaneously both intra and interspecific variation in infection-related life-history traits which is not often done (but see (Longdon et al., 2015, Imrie et al., 2021, Longdon et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2012). Indeed, most studies to date explore either inter-specific differences in susceptibility to a parasite (it can or can’t infect a given species) (Davies & Pedersen, 2008, Pfenning-Butterworth et al., 2021) or intra-specific variability in infection-related traits (infectivity, resistance etc.) due to factors such as sex, genotype and environment (Vale et al., 2008, Lambrechts et al., 2006). This work thus advances on previous studies, while at the same time showing that sex differences in parasite load are not necessarily pervasive. References Behringer DC, Butler MJ, Shields JD (2006) Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature, 441, 421–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/441421a Brierley L, Pedersen AB, Woolhouse MEJ (2019) Tissue tropism and transmission ecology predict virulence of human RNA viruses. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000206 Davies TJ, Pedersen AB (2008) Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.0284 Faria NR, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Streicker DG, Lemey P (2013) Simultaneously reconstructing viral cross-species transmission history and identifying the underlying constraints. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368, 20120196. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0196 Gilbert GS, Webb CO (2007) Phylogenetic signal in plant pathogen–host range. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 4979–4983. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607968104 Imrie RM, Roberts KE, Longdon B (2021) Between virus correlations in the outcome of infection across host species: Evidence of virus by host species interactions. Evolution Letters, 5, 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.247 Johnson PTJ, Rohr JR, Hoverman JT, Kellermanns E, Bowerman J, Lunde KB (2012) Living fast and dying of infection: host life history drives interspecific variation in infection and disease risk. Ecology Letters, 15, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01730.x Kelly CD, Stoehr AM, Nunn C, Smyth KN, Prokop ZM (2018) Sexual dimorphism in immunity across animals: a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters, 21, 1885–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13164 Lambrechts L, Chavatte J-M, Snounou G, Koella JC (2006) Environmental influence on the genetic basis of mosquito resistance to malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 1501–1506. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3483 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Day JP, Smith SCL, McGonigle JE, Cogni R, Cao C, Jiggins FM (2015) The Causes and Consequences of Changes in Virulence following Pathogen Host Shifts. PLOS Pathogens, 11, e1004728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004728 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Webster CL, Obbard DJ, Jiggins FM (2011) Host Phylogeny Determines Viral Persistence and Replication in Novel Hosts. PLOS Pathogens, 7, e1002260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002260 Pfenning-Butterworth AC, Davies TJ, Cressler CE (2021) Identifying co-phylogenetic hotspots for zoonotic disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376, 20200363. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0363 Roberts KE, Longdon B (2023) Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: examining sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility. bioRxiv 2022.11.01.514663, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663 Roy BA, Kirchner JW (2000) Evolutionary Dynamics of Pathogen Resistance and Tolerance. Evolution, 54, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00007.x Vale PF, Stjernman M, Little TJ (2008) Temperature-dependent costs of parasitism and maintenance of polymorphism under genotype-by-environment interactions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01555.x | Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility | Katherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Species vary in their susceptibility to pathogens, and this can alter the ability of a pathogen to infect a novel host. However, many factors can generate heterogeneity in infection outcomes, obscuring our ability t... | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | Anonymous, Greg Hurst | 2022-11-03 11:17:42 | View | |

06 Oct 2022

Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch.Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic contextRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia. Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009). This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value. References Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15 Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414 Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5 Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108 Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536 | Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View | |

02 May 2023

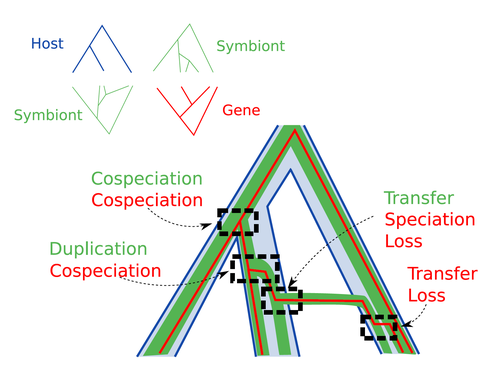

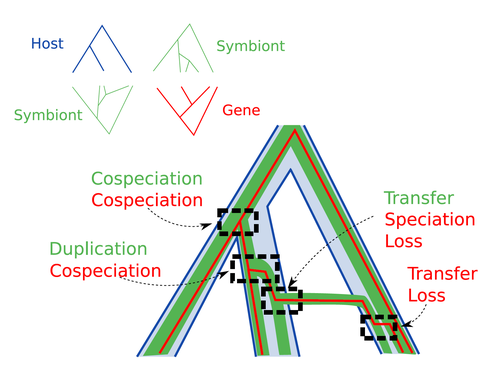

Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliationHugo Menet, Alexia Nguyen Trung, Vincent Daubin, Eric Tannier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.01.498457Reconciling molecular evolution and evolutionary ecology studies: a phylogenetic reconciliation method for gene-symbiont-host systemsRecommended by Emmanuelle Jousselin based on reviews by Vincent Berry and Catherine MatiasInteractions between species are a driving force in evolution. Many organisms host symbiotic partners that live all or part of their life in or on their host. Whether they are mutualistic or parasitic, these symbiotic associations impose strong selective pressures on both partners and affect their evolutionary trajectories. In fine, they can have a significant impact on the diversification patterns of both host and symbiont lineages, with symbiotic lineages sometimes speciating simultaneously with their hosts and/or switching from one host species to another. Long-term associations between species can also result in gene transfers between the involved organisms. Those lateral gene transfers are a source of ecological innovation but can obscure the phylogenetic signals and render the process of phylogenetic reconstructions complex (Lerat et al. 2003). Methods known as reconciliations explore similarities and differences between phylogenetic trees. They have been widely used to both compare the diversification patterns of hosts and symbionts and identify lateral gene transfers between species. Though the reconciliation approaches used in host/ symbiont and species/ gene phylogenetic studies are identical, they are always applied separately to solve either molecular evolution questions or investigate the evolution of ecological interactions. However, the two questions are often intimately linked and the current interest in multi-level systems (e.g. the holobiont concept) calls for a unique model that will take into account three-level nested organization (gene/symbiont/ host) where both symbiont and genes can transfer among hosts. Here Menet and collaborators (2023) provide such a model to produce three-level reconciliations. In order to do so, they extend the two-level reconciliation model implemented in “ALE” software (Szöllősi et al. 2013), one of the most used and proven reconciliation methods. Briefly, given a symbiont gene tree, a symbiont tree and a host tree, as in previous reconciliation models, the symbiont tree is mapped onto the host tree by mixing three types of events: Duplication, Transfer or Loss (DTL), with a possibility of the symbiont evolving temporarily outside the host phylogeny (in a “ghost” host lineage). The gene tree evolves similarly inside the symbiont tree, but horizontal transfers are constrained to symbionts co-occurring within the same host. Joint reconciliation scenarios are reconstructed and DTL event rates and likelihoods are estimated according to the model. As a nice addition, the authors propose a method to infer the symbiont phylogeny through amalgamation from gene trees and a host tree. The authors then explore the diverse possibilities offered by this method by testing it on both simulated datasets and biological datasets in order to check whether considering three nested levels is worthwhile. They convincingly show that three-level reconciliation has a better capacity to retrieve the symbiont donors and receivers of horizontal gene transfers, probably because transfers are constrained by additional elements relevant to the biological systems. Using, aphids, their obligate endosymbionts, and the symbiont genes involved in their nutritional functions, they identify horizontal gene transfers between aphid symbionts that are missed by two-level reconciliations but detected by expertise (Manzano-Marín et al. 2020). The other dataset presented here is on the human pathogen Helicobacter pylori, which history is supposed to reflect human migration. They use more than 1000 H. pylori gene families, and four populations, and use likelihood computations to compare different hypotheses on the diversification of the host. In summary, this study is a proof-of-concept of a 3-level reconciliation, where the authors manage to convey the applicability of their framework to many biological systems. Reported complexities, confirmed by reported running times, show that the method is computationally efficient. Without a doubt, the tool presented here will be very useful to evolutionary biologists who want to investigate multi-scale cophylogenies and it will move forward the study of associations between host and symbionts when symbiont genomic data are available. REFERENCES Lerat, E., Daubin, V., & Moran, N. A. (2003). From gene trees to organismal phylogeny in prokaryotes: the case of the γ-Proteobacteria. PLoS biology, 1(1), e19. Menet H, Trung AN, Daubin V, Tannier E (2023) Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliation. bioRxiv, 2022.07.01.498457, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.01.498457 Szöllősi, G. J., Rosikiewicz, W., Boussau, B., Tannier, E., & Daubin, V. (2013). Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Systematic biology, 62(6), 901-912. | Host-symbiont-gene phylogenetic reconciliation | Hugo Menet, Alexia Nguyen Trung, Vincent Daubin, Eric Tannier | <p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>Motivation:</strong> Biological systems are made of entities organized at different scales e.g. macro-organisms, symbionts, genes...) which evolve in interaction.<br>These interactions range from indepe... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Emmanuelle Jousselin | 2022-08-21 18:34:27 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer