Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Sep 2022

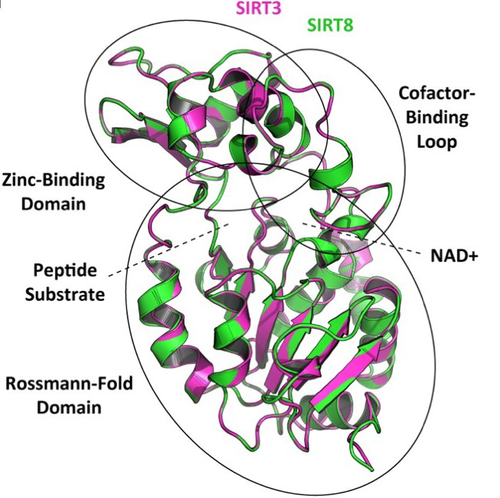

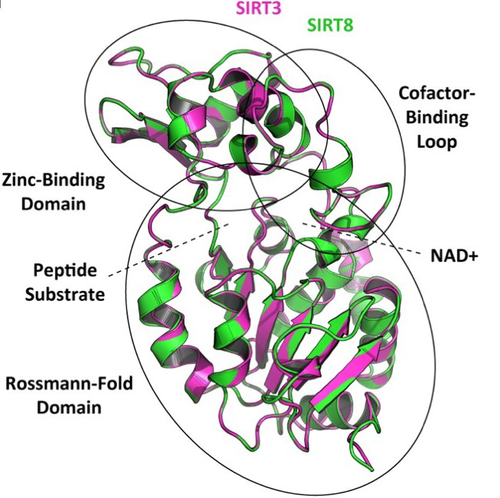

How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family memberJuan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510Making sense of vertebrate sirtuin genesRecommended by Frédéric Delsuc based on reviews by Filipe Castro, Nicolas Leurs and 1 anonymous reviewerSirtuin proteins are class III histone deacetylases that are involved in a variety of fundamental biological functions mostly related to aging. These proteins are located in different subcellular compartments and are associated with different biological functions such as metabolic regulation, stress response, and cell cycle control [1]. In mammals, the sirtuin gene family is composed of seven paralogs (SIRT1-7) grouped into four classes [2]. Due to their involvement in maintaining cell cycle integrity, sirtuins have been studied as a way to understand fundamental mechanisms governing longevity [1]. Indeed, the downregulation of sirtuin genes with aging seems to explain much of the pathophysiology that accumulates with aging [3]. Biomedical studies have thus explored the potential therapeutic implications of sirtuins [4] but whether they can effectively be used as molecular targets for the treatment of human diseases remains to be demonstrated [1]. Despite this biomedical interest and some phylogenetic analyses of sirtuin paralogs mostly conducted in mammals, a comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the sirtuin gene family at the scale of vertebrates was still lacking. In this preprint, Opazo and collaborators [5] took advantage of the increasing availability of whole-genome sequences for species representing all main groups of vertebrates to unravel the evolution of the sirtuin gene family. To do so, they undertook a phylogenomic approach in its original sense aimed at improving functional predictions by evolutionary analysis [6] in order to inventory the full vertebrate sirtuin gene repertoire and reconstruct its precise duplication history. Harvesting genomic databases, they extracted all predicted sirtuin proteins and performed phylogenetic analyses based on probabilistic inference methods. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses resulted in well-resolved and congruent phylogenetic trees dividing vertebrate sirtuin genes into three major clades. These analyses also revealed an additional eighth paralog that was previously overlooked because of its restricted phyletic distribution. This newly identified sirtuin family member (named SIRT8) was recovered with unambiguous statistical support as a sister-group to the SIRT3 clade. Comparative genomic analyses based on conserved gene synteny confirmed that SIRT8 was present in all sampled non-amniote vertebrate genomes (cartilaginous fish, bony fish, coelacanth, lungfish, and amphibians) except cyclostomes. SIRT8 has thus most likely been lost in the last common ancestor of amniotes (mammals, reptiles, and birds). Discovery of such previously unknown genes in vertebrates is not completely surprising given the plethora of high-quality genomes now available. However, this study highlights the importance of considering a broad taxonomic sampling to infer evolutionary patterns of gene families that have been mostly studied in mammals because of their potential importance for human biology. Based on its phylogenetic position as closely related to SIRT3 within class I, it could be predicted that the newly identified SIRT8 paralog likely has a deacetylase activity and is probably located in mitochondria. To test these evolutionary predictions, Opazo and collaborators [5] conducted further bioinformatics analyses and functional experiments using the elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii) as a model species. RNAseq expression data were analyzed to determine tissue-specific transcription of sirtuin genes in vertebrates, including SIRT8 found to be mainly expressed in the ovary, which suggests a potential role in biological processes associated with reproduction. The elephant shark SIRT8 protein sequence was used with other vertebrates for comparative analyses of protein structure modeling and subcellular localization prediction both pointing to a probable mitochondrial localization. The protein localization and its function were further characterized by immunolocalization in transfected cells, and enzymatic and functional assays, which all confirmed the prediction that SIRT8 proteins are targeted to the mitochondria and have deacetylase activity. The extensive experimental efforts made in this study to shed light on the function of this newly discovered gene are both rare and highly commendable. Overall, this work by Opazo and collaborators [5] provides a comprehensive phylogenomic study of the sirtuin gene family in vertebrates based on detailed evolutionary analyses using state-of-the-art phylogenetic reconstruction methods. It also illustrates the power of adopting an integrative comparative approach supplementing the reconstruction of the duplication history of the gene family with complementary functional experiments in order to elucidate the function of the newly discovered SIRT8 family member. These results provide a reference phylogenetic framework for the evolution of sirtuin genes and the further functional characterization of the eight vertebrate paralogs with potential relevance for understanding the cellular biology of aging and its associated diseases in human. References [1] Vassilopoulos A, Fritz KS, Petersen DR, Gius D (2011) The human sirtuin family: Evolutionary divergences and functions. Human Genomics, 5, 485. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-5-5-485 [2] Yamamoto H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J (2007) Sirtuin Functions in Health and Disease. Molecular Endocrinology, 21, 1745–1755. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2007-0079 [3] Morris BJ (2013) Seven sirtuins for seven deadly diseases ofaging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 56, 133–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.525 [4] Bordo D Structure and Evolution of Human Sirtuins. Current Drug Targets, 14, 662–665. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1389450111314060007 [5] Opazo JC, Vandewege MW, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Meléndez C, Luchsinger C, Cavieres VA, Vargas-Chacoff L, Morera FJ, Burgos PV, Tapia-Rojas C, Mardones GA (2022) How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member. bioRxiv, 2020.07.17.209510, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510 [6] Eisen JA (1998) Phylogenomics: Improving Functional Predictions for Uncharacterized Genes by Evolutionary Analysis. Genome Research, 8, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.8.3.163 | How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member | Juan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones | <p style="text-align: justify;">Studying the evolutionary history of gene families is a challenging and exciting task with a wide range of implications. In addition to exploring fundamental questions about the origin and evolution of genes, disent... |  | Molecular Evolution | Frédéric Delsuc | Filipe Castro, Anonymous, Nicolas Leurs | 2022-05-12 16:06:04 | View |

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

02 Feb 2024

Community structure of heritable viruses in a Drosophila-parasitoids complexJulien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.29.551099The virome of a Drosophilidae-parasitoid communityRecommended by Ben Longdon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

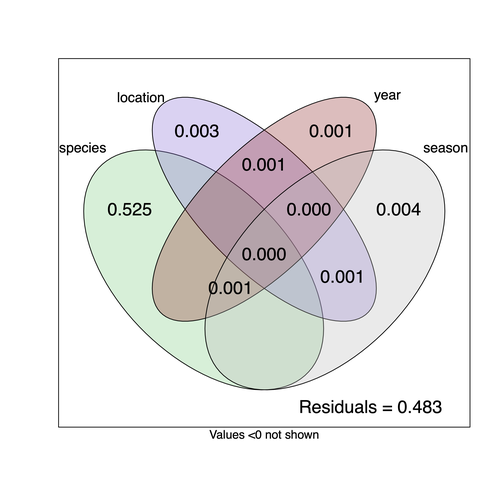

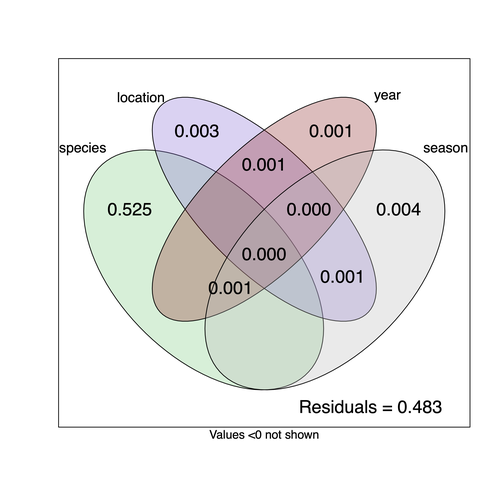

Understanding the factors that shape the virome of a host is key to understanding virus ecology and evolution (Obbard, 2018; French & Holmes, 2020). There is still much to learn about the diversity and distribution of viruses in a host community (Wille et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023). The viruses of parasitoid wasps are well studied, and their viruses, or integrated viral genes, are known to suppress their insect host’s immune response to enhance parasitoid survival (Herniou et al., 2013; Coffman et al., 2022). Likewise, the insect virome is being increasingly well studied (Shi et al., 2016), with the virome of Drosophila species being particularly well characterised over the best part of the last century (L'Heritier & Teissier, 1937; L'Heritier, 1970; Brun & Plus, 1980; Longdon et al., 2010; Longdon et al., 2011; Longdon et al., 2012; Webster et al., 2015; Webster et al., 2016; Medd et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2021). However, the viromes of parasitoids and their insect host communities have been less well studied (Leigh et al., 2018; Caldas-Garcia et al., 2023), and the inherent connectivity between parasitoids and their hosts provides an interesting system to study virus host range and cross-species transmission. Here, Varaldi et al (Varaldi et al., 2024) have examined the viruses associated with a community of nine Drosophilidae hosts and six parasitoids. Using both RNA and DNA sequencing of insects reared for two generations, they selected viruses that are maintained in the lab either via vertical transmission or contamination of rearing medium. From 55 pools of insects they found 53 virus-like sequences, 37 of which were novel. Parasitoids were host to nearly twice as many viruses as their Drosophila hosts, although they note this could be due to differences in the rearing temperatures of the hosts. They next quantified if species, year, season, or location played a role in structuring the virome, finding only a significant effect of host species, which explained just over 50% of the variation in virus distribution. No evidence was found of related species sharing more similar virus communities. Although looking at a limited number of species, this suggests that these viruses are not co-speciating or preferentially host switching between closely related species. Finally, they carried out crosses between lines of the parasitoid Leptopilina heterotoma that were infected and uninfected for a novel Iflavirus found in their sequencing data. They found evidence of high levels of maternal transmission and lower level horizontal transmission between wasp larvae parasitising the same host. No evidence of changes in parasitoid-induced mortality, developmental success or the sex ratio was found in iflavirus-infected parasitoids. Interestingly individuals infected with this RNA virus also contained viral DNA, but this did not appear to be integrated into the wasp genome. Overall, this work has taken the first steps in examining the community structure of the virome of parasitoids together with their Drosophilidae hosts. This work will not doubt stimulate follow-up studies to explore the evolution and ecology of these novel virus communities. References Brun G, Plus N (1980) The viruses of Drosophila. In: The genetics and biology of Drosophila eds Ashburner M & Wright TRF), pp. 625-702. Academic Press, New York. | Community structure of heritable viruses in a *Drosophila*-parasitoids complex | Julien Varaldi, David Lepetit, Nelly Burlet, Camille Faber, Bérénice Baretje, Roland Allemand | <p style="text-align: justify;">The diversity and phenotypic impacts related to the presence of heritable bacteria in insects have been extensively studied in the last decades. On the contrary, heritable viruses have been overlooked for several re... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Ben Longdon | 2023-08-03 01:07:43 | View | |

28 Feb 2023

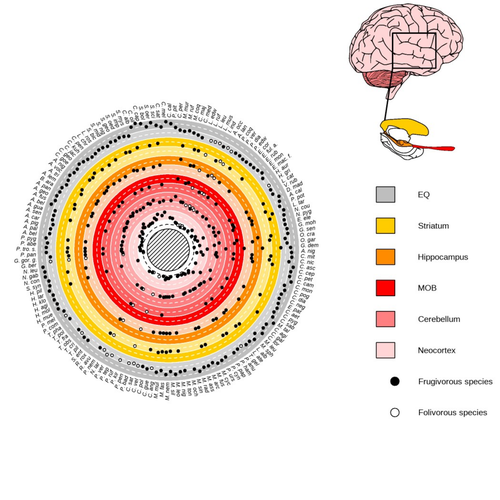

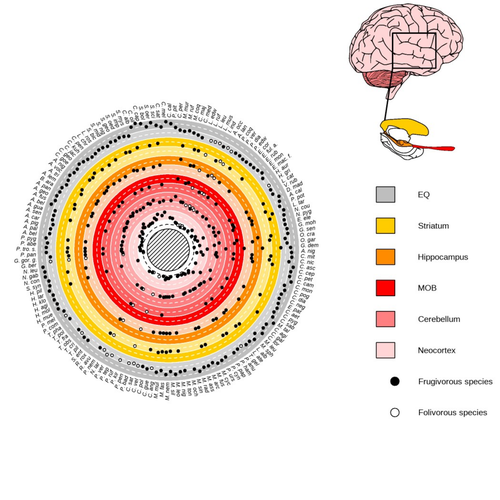

Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architectureBenjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912Macroevolutionary drivers of brain evolution in primatesRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Paula Gonzalez, Orlin Todorov and 3 anonymous reviewersStudying the evolution of animal cognition is challenging because many environmental and species-related factors can be intertwined, which is further complicated when looking at deep-time evolution. Previous knowledge has emphasized the role of intraspecific interactions in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. However, much less is known about such an effect at the interspecific level. Yet, the coexistence of different species in the same geographic area at a given time (sympatry) can impact the evolutionary history of species through character displacement due to biotic interactions. Trait evolution has been observed and tested with morphological external traits but more rarely with brain evolution. Compared to most species’ traits, brain evolution is even more delicate to assess since specific brain regions can be involved in different functions, may they be individual-based and social-based information processing. In a very original and thoroughly executed study, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) addressed the question: How does the co-occurrence of congeneric species shape brain evolution and influence species diversification? By considering brain size as a proxy for cognition, they evaluated whether species sympatry impacted the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates. Fruit resources are hard to find, not continuous through time, heterogeneously distributed across space, but can be predictable. Hence, cognition considerably shapes the foraging strategy and competition for food access can be fierce. Over long timescales, it remains unclear whether brain size and the pace of species diversification are linked in the context of sympatry, and if so how. Recent studies have found that larger brain sizes can be associated with higher diversification rates in birds (Sayol et al. 2019). Similarly, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) thus wondered if the evolution of brain size in primates impacted their dynamic of species diversification, which has been suggested (Melchionna et al. 2020) but not tested. Prior to anything, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) had to retrace the evolutionary history of sympatry between frugivorous primate lineages through time using the primate tree of life, species’ extant distribution, and process-based models to estimate ancestral range evolution. To infer the effect of species sympatry on the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates, the authors evaluated the support for phylogenetic models of brain size evolution accounting or not for species sympatry and investigated the directionality of the selection induced by sympatry on brain size evolution. Finally, to better understand the impact of cognition and interactions between primates on their evolutionary success, they tested for correlations between brain size or species’ sympatry and species diversification. Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) found that the evolution of the whole brain or brain regions used in immediate information processing was best fitted with models not considering sympatry. By contrast, models considering species sympatry best predicted the evolution of brain regions related to long-term memory of interactions with the socio-ecological environment, with a decrease in their size along with stronger sympatry. Specifically, they found that sympatry was associated with a decrease in the relative size of the hippocampus and striatum, but had no significant effect on the neocortex, cerebellum, or overall brain size. The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a crucial role in processing and memorizing spatiotemporal information, which is relevant for frugivorous primates in their foraging behavior. The study suggests that competition between sympatric species for limited food resources may lead to a more complex and unpredictable food distribution, which may in turn render cognitive foraging not advantageous and result in a selection for smaller brain regions involved in foraging. Niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry may also impact cognitive abilities, with more specialized diets requiring lower cognitive abilities and smaller brain region sizes. On the other hand, the absence of an effect of sympatry on brain regions involved in immediate sensory information processing, such as the cerebellum and neocortex, suggests that foragers do not exploit cues left out by sympatric heterospecific species, or they may discard environmental cues in favor of social cues. This is a remarkable study that highlights the importance of considering the impact of ecological factors, such as sympatry, on the evolution of specific brain regions involved in cognitive processes, and the potential trade-offs in brain region size due to niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms behind these effects and to test for the possible role of social cues in the evolution of brain regions. This study provides insights into the selective pressures that shape brain evolution in primates. References Melchionna M, Mondanaro A, Serio C, Castiglione S, Di Febbraro M, Rook L, Diniz-Filho JAF, Manzi G, Profico A, Sansalone G, Raia P (2020) Macroevolutionary trends of brain mass in Primates. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz161 Robira B, Perez-Lamarque B (2023) Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture. bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.490912, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912 Sayol F, Lapiedra O, Ducatez S, Sol D (2019) Larger brains spur species diversification in birds. Evolution, 73, 2085–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13811 | Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture | Benjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque | <p style="text-align: justify;">The main hypotheses on the evolution of animal cognition emphasise the role of conspecifics in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. Yet, space is often simultaneously occupied by multiple sp... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2022-05-10 13:43:02 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

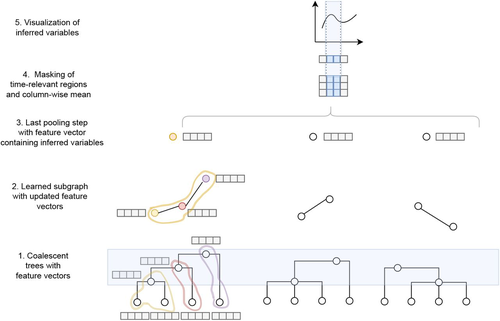

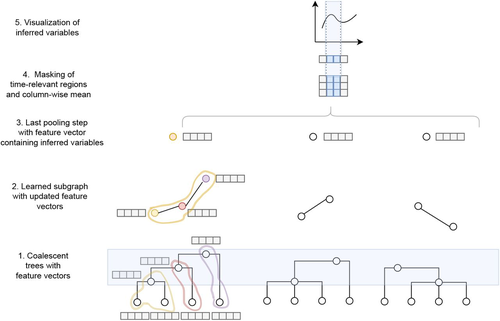

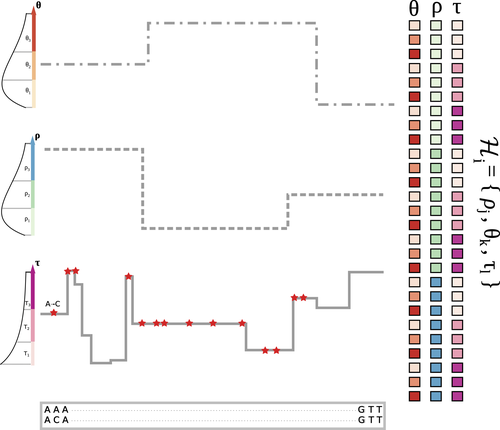

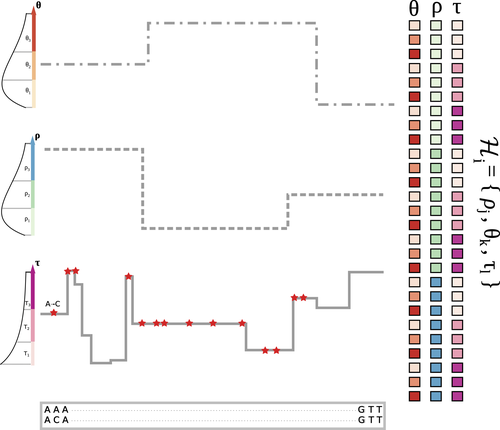

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasitesHannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259Modelling parasitoid virulence evolution with seasonalityRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers

The harm most parasites cause to their host, i.e. the virulence, is a mystery because host death often means the end of the infectious period. For obligate killer parasites, or “parasitoids”, that need to kill their host to transmit to other hosts the question is reversed. Indeed, more rapid host death means shorter generation intervals between two infections and mathematical models show that, in the simplest settings, natural selection should always favour more virulent strains (Levin and Lenski, 1983). Adding biological details to the model modifies this conclusion and, for instance, if the relationship between the infection duration and the number of parasites transmission stages produced in a host is non-linear, strains with intermediate levels of virulence can be favoured (Ebert and Weisser 1997). Other effects, such as spatial structure, could yield similar effects (Lion and van Baalen, 2007). In their study, MacDonald et al. (2021) explore another type of constraint, which is seasonality. Earlier studies, such as that by Donnelly et al. (2013) showed that this constraint can affect virulence evolution but they had focused on directly transmitted parasites. Using a mathematical model capturing the dynamics of a parasitoid, MacDonald et al. (2021) show if two main assumptions are met, namely that at the end of the season only transmission stages (or “propagules”) survive and that there is a constant decay of these propagules with time, then strains with intermediate levels of virulence are favoured. Practically, the authors use delay differential equations and an adaptive dynamics approach to identify evolutionary stable strategies. As expected, the longer the short the season length, the higher the virulence (because propagule decay matters less). The authors also identify a non-linear relationship between the variation in host development time and virulence. Generally, the larger the variation, the higher the virulence because the parasitoid has to kill its host before the end of the season. However, if the variation is too wide, some hosts become physically impossible to use for the parasite, whence a decrease in virulence. Finally, MacDonald et ali. (2021) show that the consequence of adding trade-offs between infection duration and the number of propagules produced is in line with earlier studies (Ebert and Weisser 1997). These mathematical modelling results provide testable predictions for using well-described systems in evolutionary ecology such as daphnia parasitoids, baculoviruses, or lytic phages. Reference Donnelly R, Best A, White A, Boots M (2013) Seasonality selects for more acutely virulent parasites when virulence is density dependent. Proc R Soc B, 280, 20122464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2464 Ebert D, Weisser WW (1997) Optimal killing for obligate killers: the evolution of life histories and virulence of semelparous parasites. Proc R Soc B, 264, 985–991. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0136 Levin BR, Lenski RE (1983) Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M eds. Coevolution. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 99–127. Lion S, van Baalen M (2008) Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecol. Lett., 11, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x MacDonald H, Akçay E, Brisson D (2021) Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites. bioRxiv, 2021.03.13.435259, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259 | Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites | Hannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">The traditional mechanistic trade-offs resulting in a negative correlation between transmission and virulence are the foundation of nearly all current theory on the evolution of parasite virulence. Several ecologica... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2021-03-14 13:47:33 | View | |

13 Apr 2023

The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variationGustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667An unusual suspect: the mutation landscape as a determinant of local variation in nucleotide diversityRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by David Castellano and 1 anonymous reviewerSometimes, important factors for explaining biological processes fall through the cracks, and it is only through careful modeling that their importance eventually comes out to light. In this study, Barroso and Dutheil introduce a new method based on the sequentially Markovian coalescent (SMC, Marjoran and Wall 2006) for jointly estimating local recombination and coalescent rates along a genome. Unlike previous SMC-based methods, however, their method can also co-estimate local patterns of variation in mutation rates. This is a powerful improvement which allows them to tackle questions about the reasons for the extensive variation in nucleotide diversity across the chromosomes of a species - a problem that has plagued the minds of population geneticists for decades (Begun and Aquadro 1992, Andolfatto 2007, McVicker et al., 2009, Pouyet and Gilbert 2021). The authors find that variation in de novo mutation rates appears to be the most important factor in determining nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster. Though seemingly contradicting previous attempts at addressing this problem (Comeron 2014), they take care to investigate and explain why that might be the case. Barroso and Dutheil have also taken care to carefully explain the details of their new approach and have carried a very thorough set of analyses comparing competing explanations for patterns of nucleotide variation via causal modeling. The reviewers raised several issues involving choices made by the authors in their analysis of variance partitioning, the proper evaluation of the role of linked selection and the recombination rate estimates emerging from their model. These issues have all been extensively addressed by the authors, and their conclusions seem to remain robust. The study illustrates why the mutation landscape should not be ignored as an important determinant of local variation in genetic diversity, and opens up questions about the generalizability of these results to other organisms. REFERENCES Andolfatto, P. (2007). Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome research, 17(12), 1755-1762. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.6691007 Barroso, G. V., & Dutheil, J. Y. (2021). The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation. bioRxiv, 2021.09.16.460667, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.16.460667 Begun, D. J., & Aquadro, C. F. (1992). Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature, 356(6369), 519-520. https://doi.org/10.1038/356519a0 Comeron, J. M. (2014). Background selection as baseline for nucleotide variation across the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genetics, 10(6), e1004434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004434 Marjoram, P., & Wall, J. D. (2006). Fast" coalescent" simulation. BMC genetics, 7, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-7-16 McVicker, G., Gordon, D., Davis, C., & Green, P. (2009). Widespread genomic signatures of natural selection in hominid evolution. PLoS genetics, 5(5), e1000471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471 Pouyet, F., & Gilbert, K. J. (2021). Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. Peer Community Journal, 1, e27. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.16 | The landscape of nucleotide diversity in Drosophila melanogaster is shaped by mutation rate variation | Gustavo V Barroso, Julien Y Dutheil | <p style="text-align: justify;">What shapes the distribution of nucleotide diversity along the genome? Attempts to answer this question have sparked debate about the roles of neutral stochastic processes and natural selection in molecular evolutio... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-10-30 07:52:07 | View | |

05 Jan 2023

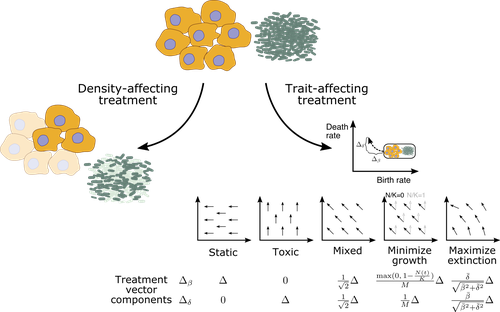

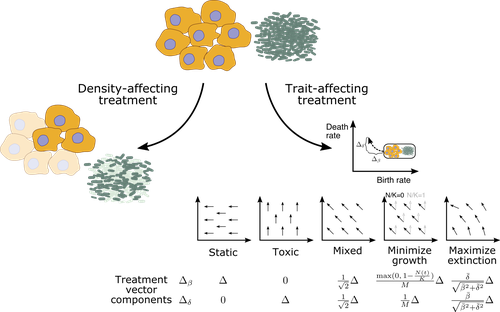

Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populationsMichael Raatz, Arne Traulsen https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570Trait trajectories in evolving populations: insights from mathematical modelsRecommended by Dominik Wodarz based on reviews by Rob Noble and 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of cells within organisms can be an important determinant of disease. This is especially clear in the emergence of tumors and cancers from the underlying healthy tissue. In the healthy state, homeostasis is maintained through complex regulatory processes that ensure a relatively constant population size of cells, which is required for tissue function. Tumor cells escape this homeostasis, resulting in uncontrolled growth and consequent disease. Disease progression is driven by further evolutionary processes within the tumor, and so is the response of tumors to therapies. Therefore, evolutionary biology is an important component required for a better understanding of carcinogenesis and the treatment of cancers. In particular, evolutionary theory helps define the principles of mutant evolution and thus to obtain a clearer picture of the determinants of tumor emergence and therapy responses. The study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] makes an important contribution in this respect. They use mathematical and computational models to investigate trait evolution in the context of evolutionary rescue, motivated by the dynamics of cancer, and also bacterial infections. This study views the establishment of tumors as cell dynamics in harsh environments, where the population is prone to extinction unless mutants emerge that increase evolutionary fitness, allowing them to expand (evolutionary rescue). The core processes of the model include growth, death, and mutations. Random mutations are assumed to give rise to cell lineages with different trait combinations, where the birth and death rates of cells can change. The resulting evolutionary trajectories are investigated in the models, and interesting new results were obtained. For example, the turnover of the population was identified as an important determinant of trait evolution. Turnover is defined as the balance between birth and death, with large rates corresponding to fast turnover and small rates to slow turnover. It was found that for fast cell turnover, a given adaptive step in the trait space results in a smaller increase in survival probability than for cell populations with slower turnover. In other words, evolutionary rescue is more difficult to achieve for fast compared to slow turnover populations. While more mutants can be produced for faster cell turnover rates, the analysis showed that this is not sufficient to overcome the barrier to the evolutionary rescue. This result implies that aggressive tumors with fast cell birth and death rates are less likely to persist and progress than tumors with lower turnover rates. This work emphasizes the importance of measuring the turnover rate in different tumors to advance our understanding of the determinants of tumor initiation and progression. The authors discuss that the well-documented heterogeneity in tumors likely also applies to cellular turnover. If a tumor consists of sub-populations with faster and slower turnover, it is possible that a slower turnover cell clone (e.g. characterized by a degree of dormancy) would enjoy a selective advantage. Another source of heterogeneity in turnover could be given by the hierarchical organization of tumors. Similar to the underlying healthy tissue, many tumors are thought to be maintained by a population of cancer stem cells, while the tumor bulk is made up of more differentiated cells. Tissue stem cells tend to be characterized by a lower turnover than progenitor or transit-amplifying cells. Depending on the assumptions about the self-renewal capacity of these different cell populations, the potential for evolutionary rescue could be different depending on the cell compartment in which the mutant emerges. This might be interesting to explore in the future. There are also implications for treatment. Two types of treatment were investigated: density-affecting treatments in which the density of cells is reduced without altering their trait parameters, and trait-affecting treatments in which the birth and/or death rates are altered. Both types of treatment were found to change the trajectories of trait adaptation, which has potentially important practical implications. Interestingly, it was found that competitive release during treatment can result in situations where after treatment cessation, the non-extinct populations recover to reach sizes that were higher than in the absence of treatment. This points towards the potential of adaptive therapy approaches, where sensitive cells are maintained to some extent to suppress resistant clones [2] competitively. In this context, it is interesting that the success of such approaches might also depend on the turnover of the tumor cell population, as shown by a recent mathematical modeling study [3]. In particular, it was found that adaptive therapy is less likely to work for slow compared to fast turnover tumors. Yet, the current study by Raatz and Traulsen [1] suggests that tumors are more likely to evolve in a slow turnover setting. While there is strong relevance of this analysis for tumor evolution, the results generated in this study have more general relevance. Besides tumors, the paper discusses applications to bacterial disease dynamics in some detail, which is also interesting to compare and contrast to evolutionary processes in cancer. Overall, this study provides insights into the dynamics of evolutionary rescue that represent valuable additions to evolutionary theory. References [1] Raatz M, Traulsen A (2023) Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.496570, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.496570 [2] Gatenby RA, Silva AS, Gillies RJ, Frieden BR (2009) Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 69, 4894–4903. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3658 [3] Strobl MAR, West J, Viossat Y, Damaghi M, Robertson-Tessi M, Brown JS, Gatenby RA, Maini PK, Anderson ARA (2021) Turnover Modulates the Need for a Cost of Resistance in Adaptive Therapy. Cancer Research, 81, 1135–1147. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0806 | Promoting extinction or minimizing growth? The impact of treatment on trait trajectories in evolving populations | Michael Raatz, Arne Traulsen | <p style="text-align: justify;">When cancers or bacterial infections establish, small populations of cells have to free themselves from homoeostatic regulations that prevent their expansion. Trait evolution allows these populations to evade this r... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory | Dominik Wodarz | 2022-06-18 08:44:37 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer