Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Mar 2019

Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradientAndrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine https://doi.org/10.1101/236646One (more) step towards a dynamic view of the Latitudinal Diversity GradientRecommended by Joaquín Hortal and Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Joaquín Hortal, Arne Mooers, Joaquin Calatayud and 2 anonymous reviewers

The Latitudinal Diversity Gradient (LDG) has fascinated natural historians, ecologists and evolutionary biologists ever since [1] described it about 200 years ago [2]. Despite such interest, agreement on the origin and nature of this gradient has been elusive. Several tens of hypotheses and models have been put forward as explanations for the LDG [2-3], that can be grouped in ecological, evolutionary and historical explanations [4] (see also [5]). These explanations can be reduced to no less than 26 hypotheses, which account for variations in ecological limits for the establishment of progressively larger assemblages, diversification rates, and time for species accumulation [5]. Besides that, although in general the tropics hold more species, different taxa show different shapes and rates of spatial variation [6], and a considerable number of groups show reverse patterns, with richer assemblages in cold temperate regions (see e.g. [7-9]). References | Ancient tropical extinctions contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient | Andrea S. Meseguer, Fabien Condamine | <p>Biodiversity currently peaks at the equator, decreasing toward the poles. Growing fossil evidence suggest that this hump-shaped latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG) has not been persistent through time, with similar species diversity across lat... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Joaquín Hortal | 2017-12-20 14:58:01 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

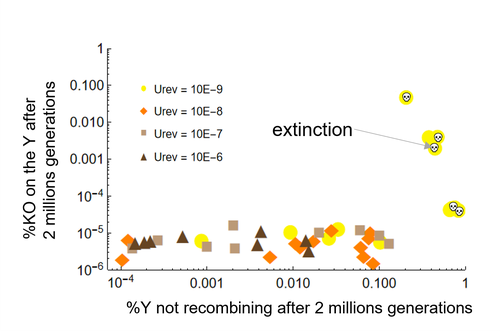

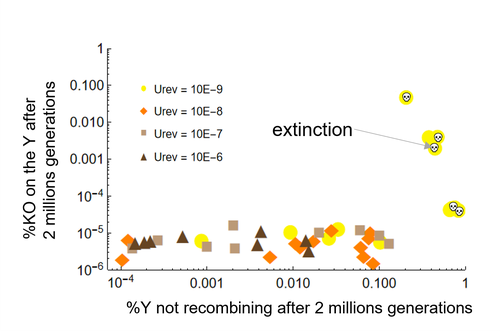

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View | |

15 Feb 2019

Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approachRubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez https://doi.org/10.1101/356147Sometimes, sex is in the headRecommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Plants display an amazing diversity of reproductive strategies with and without sex. This diversity is particularly remarkable in flowering plants, as highlighted by Charles Darwin, who wrote several botanical books scrutinizing plant reproduction. One particularly influential work concerned floral variation [1]. Darwin recognized that flowers may present different forms within a single population, with or without sex specialization. The number of species concerned is small, but they display recurrent patterns, which made it possible for Darwin to invoke natural and sexual selection to explain them. Most of early evolutionary theory on the evolution of reproductive strategies was developed in the first half of the 20th century and was based on animals. However, the pioneering work by David Lloyd from the 1970s onwards excited interest in the diversity of plant sexual strategies as models for testing adaptive hypotheses and predicting reproductive outcomes [2]. The sex specialization of individual flowers and plants has since become one of the favorite topics of evolutionary biologists. However, attention has focused mostly on cases related to sex differentiation (dioecy and associated conditions [3]). Separate unisexual flower types on the same plant (monoecy and related cases, rendering the plant functionally hermaphroditic) have been much less studied, apart from their possible role in the evolution of dioecy [4] or their association with particular modes of pollination [5]. References [1] Darwin, C. (1877). The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. John Murray. | Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approach | Rubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez | <p>Male and female unisexual flowers have repeatedly evolved from the ancestral bisexual flowers in different lineages of flowering plants. This sex specialization in different flowers often occurs within inflorescences. We hypothesize that inflor... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Juan Arroyo | Jana Vamosi, Marcial Escudero, Anonymous | 2018-06-27 10:49:52 | View |

04 Mar 2024

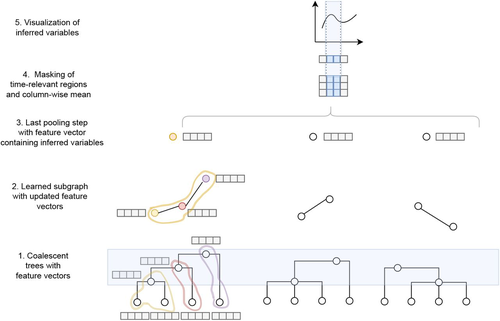

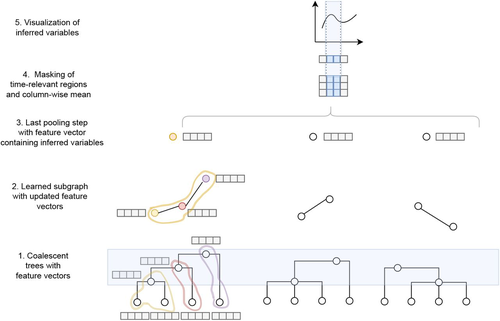

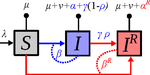

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

11 Jun 2019

A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolutionThibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz https://doi.org/10.1101/505610Young sex chromosomes discovered in white-eye birdsRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by Gabriel Marais, Melissa Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent advances in next-generation sequencing are allowing us to uncover the evolution of sex chromosomes in non-model organisms. This study [1] represents an example of this application to birds of two Sylvioidea species from the genus Zosterops (commonly known as white-eyes). The study is exemplary in the amount and types of data generated and in the thoroughness of the analysis applied. Both male and female genomes were sequenced to allow the authors to identify sex-chromosome specific scaffolds. These data were augmented by generating the transcriptome (RNA-seq) data set. The findings after the analysis of these extensive data are intriguing: neoZ and neoW chromosome scaffolds and their breakpoints were identified. Novel sex chromosome formation appears to be accompanied by translocation events. The timing of formation of novel sex chromosomes was identified using molecular dating and appears to be relatively recent. Yet first signatures of distinct evolutionary patterns of sex chromosomes vs. autosomes could be already identified. These include the accumulation of transposable elements and changes in GC content. The changes in GC content could be explained by biased gene conversion and altered recombination landscape of the neo sex chromosomes. The authors also study divergence and diversity of genes located on the neo sex chromosomes. Here their findings appear to be surprising and need further exploration. The neoW chromosome already shows unique patterns of divergence and diversity at protein-coding genes as compared with genes on either neoZ or autosomes. In contrast, the genes on the neoZ chromosome do not display divergence or diversity patterns different from those for autosomes. This last observation is puzzling and I believe should be explored in further studies. Overall, this study significantly advances our knowledge of the early stages of sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates, provides an example of how such a study could be conducted in other non-model organisms, and provides several avenues for future work. References [1] Leroy T., Anselmetti A., Tilak M.K., Bérard S., Csukonyi L., Gabrielli M., Scornavacca C., Milá B., Thébaud C. and Nabholz B. (2019). A bird’s white-eye view on neo-sex chromosome evolution. bioRxiv, 505610, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/505610 | A bird’s white-eye view on neosex chromosome evolution | Thibault Leroy, Yoann Anselmetti, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sèverine Bérard, Laura Csukonyi, Maëva Gabrielli, Céline Scornavacca, Borja Milá, Christophe Thébaud, Benoit Nabholz | <p>Chromosomal organization is relatively stable among avian species, especially with regards to sex chromosomes. Members of the large Sylvioidea clade however have a pair of neo-sex chromosomes which is unique to this clade and originate from a p... |  | Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Kateryna Makova | 2019-01-24 14:17:15 | View | |

27 Jul 2020

Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebratesJuan C. Opazo, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Scott V. Edwards https://doi.org/10.1101/794404An evolutionary view of a biomedically important gene familyRecommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis manuscript [1] investigates the evolutionary history of the DAN gene family—a group of genes important for embryonic development of limbs, kidneys, and left-right axis speciation. This gene family has also been implicated in a number of diseases, including cancer and nephropathies. DAN genes have been associated with the inhibition of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. Despite this detailed biochemical and functional knowledge and clear importance for development and disease, evolution of this gene family has remained understudied. The diversification of this gene family was investigated in all major groups of vertebrates. The monophyly of the gene members belonging to this gene family was confirmed. A total of five clades were delineated, and two novel lineages were discovered. The first lineage was only retained in cephalochordates (amphioxus), whereas the second one (GREM3) was retained by cartilaginous fish, holostean fish, and coelanth. Moreover, the patterns of chromosomal synteny in the chromosomal regions harboring DAN genes were investigated. Additionally, the authors reconstructed the ancestral gene repertoires and studied the differential retention/loss of individual gene members across the phylogeny. They concluded that the ancestor of gnathostome vertebrates possessed eight DAN genes that underwent differential retention during the evolutionary history of this group. During radiation of vertebrates, GREM1, GREM2, SOST, SOSTDC1, and NBL1 were retained in all major vertebrate groups. At the same time, GREM3, CER1, and DAND5 were differentially lost in some vertebrate lineages. At least two DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of vertebrates, and at least three DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of chordates. Therefore the patterns of retention and diversification in this gene family appear to be complex. Evolutionary slowdown for the DAN gene family was observed in mammals, suggesting selective constraints. Overall, this article puts the biomedical importance of the DAN family in the evolutionary perspective. References [1] Opazo JC, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Edwards SV (2020) Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 794404, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/794404 | Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates | Juan C. Opazo, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Scott V. Edwards | <p>The DAN gene family (DAN, Differential screening-selected gene Aberrant in Neuroblastoma) is a group of genes that is expressed during development and plays fundamental roles in limb bud formation and digitation, kidney formation and morphogene... |  | Molecular Evolution | Kateryna Makova | 2019-10-15 16:43:13 | View | |

26 Nov 2019

Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studiesJobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume https://doi.org/10.1101/656413Understanding the effects of linkage and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptationRecommended by Kathleen Lotterhos based on reviews by Pär Ingvarsson and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic correlations among traits are ubiquitous in nature. However, we still have a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of trait correlations. Some genetic correlations among traits arise because of pleiotropy - single mutations or genotypes that have effects on multiple traits. Other genetic correlations among traits arise because of linkage among mutations that have independent effects on different traits. Teasing apart the differential effects of pleiotropy and linkage on trait correlations is difficult, because they result in very similar genetic patterns. However, understanding these differential effects gives important insights into how ubiquitous pleiotropy may be in nature. References [1] Chebib, J. and Guillaume, F. (2019). Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies. bioRxiv, 656413, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/656413 | Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies | Jobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume | <p>Genetic correlations between traits may cause correlated responses to selection depending on the source of those genetic dependencies. Previous models described the conditions under which genetic correlations were expected to be maintained. Sel... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Kathleen Lotterhos | 2019-06-05 13:51:43 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks?Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.550272How to survive the mutational meltdown: lessons from plant RNA virusesRecommended by Kavita Jain based on reviews by Brent Allman, Ana Morales-Arce and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough most mutations are deleterious, the strongly deleterious ones do not spread in a very large population as their chance of fixation is very small. Another mechanism via which the deleterious mutations can be eliminated is via recombination or sexual reproduction. However, in a finite asexual population, the subpopulation without any deleterious mutation will eventually acquire a deleterious mutation resulting in the reduction of the population size or in other words, an increase in the genetic drift. This, in turn, will lead the population to acquire deleterious mutations at a faster rate eventually leading to a mutational meltdown. This irreversible (or, at least over some long time scales) accumulation of deleterious mutations is especially relevant to RNA viruses due to their high mutation rate, and while the prior work has dealt with bacteriophages and RNA viruses, the study by Lafforgue et al. [1] makes an interesting contribution to the existing literature by focusing on plants. In this study, the authors enquire how despite the repeated increase in the strength of genetic drift, how the RNA viruses manage to survive in plants. Following a series of experiments and some numerical simulations, the authors find that as expected, after severe bottlenecks, the fitness of the population decreases significantly. But if the bottlenecks are followed by population expansion, the Muller’s ratchet can be halted due to the genetic diversity generated during population growth. They hypothesize this mechanism as a potential way by which the RNA viruses can survive the mutational meltdown. As a theoretician, I find this investigation quite interesting and would like to see more studies addressing, e.g., the minimum population growth rate required to counter the potential extinction for a given bottleneck size and deleterious mutation rate. Of course, it would be interesting to see in future work if the hypothesis in this article can be tested in natural populations. References [1] Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena (2024) How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology | How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? | Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena | <p>Muller's ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in small populations, resulting in a decline in overall fitness. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in experiments involving microorganisms, including ... | Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution | Kavita Jain | 2023-08-04 09:37:08 | View | ||

05 Jun 2018

The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distributionJan Engelstaedter & Nicole Fortuna https://doi.org/10.1101/209254Shift or stick? Untangling the signatures of biased host switching, and host-parasite co-speciationRecommended by Lucy Weinert based on reviews by Damien de Vienne and Nathan MeddMany emerging diseases arise by parasites switching to new host species, while other parasites seem to remain with same host lineage for very long periods of time, even over timescales where an ancestral host species splits into two or more new species. The ability to understand these dynamics would form an important part of our understanding of infectious disease. Experiments are clearly important for understanding these processes, but so are comparative studies, investigating the variation that we find in nature. Such comparative data do show strong signs of non-randomness, and this suggests that the epidemiological and ecological processes might be predictable, at least in part. For example, when we map patterns of parasite presence/absence onto host phylogenies, we often find that certain host clades harbour many more parasites than expected, or that closely-related hosts harbour closely-related parasites. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to interpret these patterns to make inferences about ecological and epidemiological processes. This is partly because non-random associations can arise in multiple ways. For example, parasites might be inherited from the common ancestor of related hosts, or might switch to new hosts, but preferentially establish on novel hosts that are closely related to their existing host. Infection might also influence the shape of host phylogeny, either by increasing the rate of host extinction or, conversely, increasing the rate of speciation (as with manipulative symbionts that might induce reproductive isolation). These various processes have, by and large, been studied in isolation, but the model introduced by Engelstädter and Fortuna [1], makes an important first step towards studying them together. Without such combined analyses, we will not be able to tell if the processes have their own unique signatures, or whether the same sort of non-randomness can arise in multiple ways. A major finding of the work is that the size of a host clade can be an important determinant of its overall infection level. This had been shown in previous work, assuming that the host phylogeny was fixed, but the current paper shows that it extends also to situations where host extinction and speciation takes place at a comparable rate to host shifting. This finding, then, calls into question the natural assumption that a clade of host species that is highly parasite ridden, must have some genetic or ecological characteristic that makes them particularly prone to infection, arguing that the clade size, rather than any characteristic of the clade members, might be the important factor. It will be interesting to see whether this prediction about clade size is borne out with comparative studies. Another feature of the study is that the framework is naturally extendable, to include further processes, such as the influence of parasite presence on extinction or speciation rates. No doubt extensions of this kind will form the basis of important future work. References [1] Engelstädter J and Fortuna NZ. 2018. The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distribution. bioRxiv 209254 ver. 5 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/209254 | The dynamics of preferential host switching: host phylogeny as a key predictor of parasite prevalence and distribution | Jan Engelstaedter & Nicole Fortuna | <p>New parasites commonly arise through host-shifts, where parasites from one host species jump to and become established in a new host species. There is much evidence that the probability of host-shifts decreases with increasing phylogenetic dist... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Lucy Weinert | 2017-10-30 02:06:06 | View | |

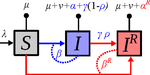

04 Nov 2020

Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistanceSamuel Alizon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.970905More intense symptoms, more treatment, more drug-resistance: coevolution of virulence and drug-resistanceRecommended by Ludek Berec based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersMathematical models play an essential role in current evolutionary biology, and evolutionary epidemiology is not an exception [1]. While the issues of virulence evolution and drug-resistance evolution resonate in the literature for quite some time [2, 3], the study by Alizon [4] is one of a few that consider co-evolution of both these traits [5]. The idea behind this study is the following: treating individuals with more severe symptoms at a higher rate (which appears to be quite natural) leads to an appearance of virulent drug-resistant strains, via treatment failure. The author then shows that virulence in drug-resistant strains may face different selective pressures than in drug-sensitive strains and hence proceed at different rates. Hence, treatment itself modulates evolution of virulence. As one of the reviewers emphasizes, the present manuscript offers a mathematical view on why the resistant and more virulent strains can be selected in epidemics. Also, we both find important that the author highlights that the topic and results of this study can be attributed to public health policies and development of optimal treatment protocols [6]. References [1] Gandon S, Day T, Metcalf JE, Grenfell BT (2016) Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends Ecol Evol 31: 776-788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistance | Samuel Alizon | <p>Antimicrobial therapeutic treatments are by definition applied after the onset of symptoms, which tend to correlate with infection severity. Using mathematical epidemiology models, I explore how this link affects the coevolutionary dynamics bet... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Ludek Berec | 2020-03-04 10:18:39 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer