Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Mar 2024

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

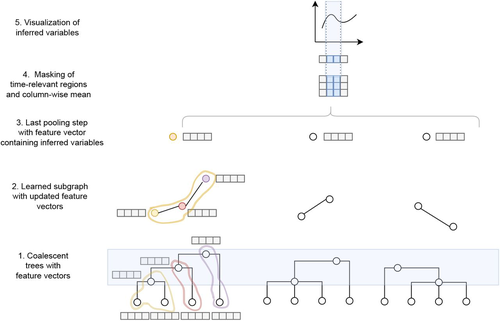

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

10 Jul 2019

Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pestGeorgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/362129The scandalous pestRecommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Koutsovoulos et al. [1] have generated and analysed the first population genomic dataset in root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Why is this interesting? For two major reasons. First, M. incognita has been documented to be apomictic, i.e., to lack any form of sex. This is a trait of major evolutionary importance, with implications on species adaptive potential. The study of genome evolution in asexuals is fascinating and has the potential to inform on the forces governing the evolution of sex and recombination. Even small amounts of sex, however, are sufficient to restore most of the population genetic properties of true sexuals [2]. Because rare events of sex can remain undetected in the field, to confirm asexuality in M. incognita using genomic data is an important step. The second reason why M. incognita is of interest is that this nematode is one of the most harmful pests currently living on earth. M. incognita feeds on the roots of many cultivated plants, including tomato, bean, and cotton, and has been of major agricultural importance for decades. A number of races were defined based on host specificity. These have played a key role in attempts to control the dynamic of M. incognita populations via crop rotations. Races and management strategies so far lack any genetic basis, hence the second major interest of this study. References [1] Koutsovoulos, G. D., Marques, E., Arguel, M. J., Duret, L., Machado, A. C. Z., Carneiro, R. M. D. G., Kozlowski, D. K., Bailly-Bechet, M., Castagnone-Sereno, P., Albuquerque, E. V., & Danchin, E. G. J. (2019). Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest. bioRxiv, 362129, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/362129 | Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest | Georgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin | <p>The most devastating nematodes to worldwide agriculture are the root-knot nematodes with Meloidogyne incognita being the most widely distributed and damaging species. This parasitic and ecological success seem surprising given its supposed obli... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | 2018-08-24 09:02:33 | View | ||

18 May 2018

Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkageKatie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins https://doi.org/10.1101/202481Differential effect of genes in diverse environments, their role in local adaptation and the interference between genes that are physically linkedRecommended by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer

The genome of eukaryotic species is a complex structure that experience many different interactions within itself and with the surrounding environment. The genetic architecture of a phenotype (that is, the set of genetic elements affecting a trait of the organism) plays a fundamental role in understanding the adaptation process of a species to, for example, different climate environments, or to its interaction with other species. Thus, it is fundamental to study the different aspects of the genetic architecture of the species and its relationship with its surronding environment. Aspects such as modularity (the number of genetic units and the degree to which each unit is affecting a trait of the organism), pleiotropy (the number of different effects that a genetic unit can have on an organism) or linkage (the degree of association between the different genetic units) are essential to understand the genetic architecture and to interpret the effects of selection on the genome. Indeed, the knowledge of the different aspects of the genetic architecture could clarify whether genes are affected by multiple aspects of the environment or, on the contrary, are affected by only specific aspects [1,2]. The work performed by Lotterhos et al. [3] sought to understand the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments in lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), considering as candidate SNPs those previously detected as a result of its extreme association patterns to different environmental variables or to extreme population differentiation. This consideration is very important because the study is only relevant if the studied markers are under the effect of selection. Otherwise, the genetic architecture of the adaptation to different environments would be masked by other (neutral) kind of associations that would be difficult to interpret [4,5]. In order to understand the relationship between genetic architecture and adaptation, it is relevant to detect the association networks of the candidate SNPs with climate variables (a way to measure modularity) and if these SNPs (and loci) are affected by single or multiple environments (a way to measure pleiotropy). The authors used co-association networks, an innovative approach in this field, to analyse the interaction between the environmental information and the genetic polymorphism of each individual. This methodology is more appropriate than other multivariate methods - such as analysis based on principal components - because it is possible to cluster SNPs based on associations with similar environmental variables. In this sense, the co-association networks allowed to both study the genetic and physical linkage between different co-associations modules but also to compare two different models of evolution: a Modular environmental response architecture (specific genes are affected by specific aspects of the environment) or a Universal pleiotropic environmental response architecture (all genes are affected by all aspects of the environment). The representation of different correlations between allelic frequency and environmental factors (named galaxy biplots) are especially informative to understand the effect of the different clusters on specific aspects of the environment (for example, the co-association network ‘Aridity’ shows strong associations with hot/wet versus cold/dry environments). The analysis performed by Lotterhos et al. [3], although it has some unavoidable limitations (e.g., only extreme candidate SNPs are selected, limiting the results to the stronger effects; the genetic and physical map is incomplete in this species), includes relevant results and also implements new methodologies in the field. To highlight some of them: the preponderance of a Modular environmental response architecture (evolution in separated modules), the detection of physical linkage among SNPs that are co-associated with different aspects of the environment (which was unexpected a priori), the implementation of co-association networks and galaxy biplots to see the effect of modularity and pleiotropy on different aspects of environment. Finally, this work contains remarkable introductory Figures and Tables explaining unambiguously the main concepts [6] included in this study. This work can be treated as a starting point for many other future studies in the field. References [1] Hancock AM, Brachi B, Faure N, Horton MW, Jarymowycz LB, Sperone FG, Toomajian C, Roux F & Bergelson J. 2011. Adaptation to climate across the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Science 334: 83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1209244 | Modularity of genes involved in local adaptation to climate despite physical linkage | Katie E. Lotterhos, Sam Yeaman, Jon Degner, Sally Aitken, Kathryn Hodgins | <p>Background: Physical linkage among genes shaped by different sources of selection is a fundamental aspect of genetic architecture. Theory predicts that evolution in complex environments selects for modular genetic architectures and high recombi... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution | Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins | 2017-10-15 19:21:57 | View | |

05 Aug 2020

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaDjampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognitaRecommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms. References [1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1 | Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View | ||

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View | |

05 Oct 2017

Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local AdaptationStewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips 10.1101/145169A new approach to identifying drivers of local adaptationRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer based on reviews by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Thomas LenormandLocal adaptation, the higher fitness a population achieves in its local “home” environment relative to other environments is a crucial phase in the divergence of populations, and as such both generates and maintains diversity. Local adaptation is enhanced by selection and genetic variation in the relevant traits, and decreased by gene flow and genetic drift. Demonstrating local adaptation is laborious, and is typically done with a reciprocal transplant design [1], documenting repeated geographic clines [e.g. 2, 3] also provides strong evidence of local adaptation. Even when well documented, it is often unknown which aspects of the environment impose selection. Indeed, differences in environment between different sites that are measured during studies of local adaptation explain little of the variance in the degree of local adaptation [4]. This poses a problem to population management. Given climate change and habitat destruction, understanding the environmental drivers of local adaptation can be crucially important to conducting successful assisted migration or targeted gene flow. In this manuscript, Macdonald et al. [5] propose a means of identifying which aspects of the environment select for local adaptation without conducting a reciprocal transplant experiment. The idea is that the strength of relationships between traits and environmental variables that are due to plastic responses to the environment will not be influenced by gene flow, but the strength of trait-environment relationships that are due to local adaptation should decrease with gene flow. This then can be used to reduce the somewhat arbitrary list of environmental variables on which data are available down to a targeted list more likely to drive local adaptation in specific traits. To perform such an analysis requires three things: 1) measurements of traits of interest in a species across locations, 2) an estimate of gene flow between locations, which can be replaced with a biologically meaningful estimate of how well connected those locations are from the point of view of the study species, and 3) data on climate and other environmental variables from across a species’ range, many of which are available on line. Macdonald et al. [5] demonstrate their approach using a skink (Lampropholis coggeri). They collected morphological and physiological data on individuals from multiple populations. They estimated connectivity among those locations using information on habitat suitability and dispersal potential [6], and gleaned climatic data from available databases and the literature. They find that two physiological traits, the critical minimum and maximum temperatures, show the strongest signs of local adaptation, specifically local adaptation to annual mean precipitation, precipitation of the driest quarter, and minimum annual temperature. These are then aspects of skink phenotype and skink habitats that could be explored further, or could be used to provide background information if migration efforts, for example for genetic rescue [7] were initiated. The approach laid out has the potential to spark a novel genre of research on local adaptation. It its simplest form, knowing that local adaptation is eroded by gene flow, it is intuitive to consider that if connectivity reduces the strength of the relationship between an environmental variable and a trait, that the trait might be involved in local adaptation. The approach is less intuitive than that, however – it relies not connectivity per-se, but the interaction between connectivity and different environmental variables and how that interaction alters trait-environment relationships. The authors lay out a number of useful caveats and potential areas that could use further development. It will be interesting to see how the community of evolutionary biologists responds. References [1] Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL and Gandon S. 2013. A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16: 1195-1205. doi: 10.1111/ele.12150 [2] Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D and Serra L. 2000. Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science, 287: 308-309. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.308 [3] Milesi P, Lenormand T, Lagneau C, Weill M and Labbé P. 2016. Relating fitness to long-term environmental variations in natura. Molecular Ecology, 25: 5483-5499. doi: 10.1111/mec.13855 [4] Hereford, J. 2009. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. The American Naturalist 173: 579-588. doi: 10.1086/597611 [5] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J and Phillips BL. 2017. Using connectivity to identify climatic drivers of local adaptation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 of October 4, 2017. doi: 10.1101/145169 [6] Macdonald SL, Llewelyn J, Moritz C and Phillips BL. 2017. Peripheral isolates as sources of adaptive diversity under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5:88. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00088 [7] Whiteley AR, Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC and Tallmon DA. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.009 | Using Connectivity To Identify Climatic Drivers Of Local Adaptation | Stewart L. Macdonald, John Llewelyn, Ben Phillips | Despite being able to conclusively demonstrate local adaptation, we are still often unable to objectively determine the climatic drivers of local adaptation. Given the rapid rate of global change, understanding the climatic drivers of local adapta... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | Thomas Lenormand | 2017-06-06 13:06:54 | View |

06 May 2019

When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexualsFlorian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/433235Fisher to the rescueRecommended by François Blanquart and Florence Débarre based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe ability of a population to adapt to a new niche is an important phenomenon in evolutionary biology. The colonisation of a new volcanic island by plant species; the colonisation of a host treated by antibiotics by a-resistant strain; the Ebola virus transmitting from bats to humans and spreading epidemically in Western Africa, are all examples of a population invading a new niche, adapting and eventually establishing in this new environment. Adaptation to a new niche can be studied using source-sink models. In the original environment —the “source”—, the population enjoys a positive growth-rate and is self-sustaining, while in the new environment —the “sink”— the population has a negative growth rate and is able to sustain only by the continuous influx of migrants from the source. Understanding the dynamics of adaptation to the sink environment is challenging from a theoretical standpoint, because it requires modelling the demography of the sink as well as the transient dynamics of adaptation. Moreover, local selection in the sink and immigration from the source create distributions of genotypes that complicate the use of many common mathematical approaches. In their paper, Lavigne et al. [1], develop a new deterministic model of adaptation to a harsh sink environment in an asexual species. The fitness of an individual is maximal when a number of phenotypes are tuned to an optimal value, and declines monotonously as phenotypes are further away from this optimum. This model —called Fisher’s Geometric Model— generates a GxE interaction for fitness because the phenotypic optimum in the sink environment is distinct from that in the source environment [2]. The authors circumvent mathematical difficulties by developing an original approach based on tracking the deterministic dynamics of the cumulant generating function of the fitness distribution in the sink. They derive a number of important results on the dynamics of adaptation to the sink:

In conclusion, this theoretical work presents a method based on Fisher’s Geometric Model and the use of cumulant generating functions to resolve some aspects of adaptation to a sink environment. It generates a number of theoretical predictions for the adaptive colonisation of a sink by an asexual species with some standing genetic variation. It will be a fascinating task to examine whether these predictions hold in experimental evolution systems: will we observe the four phases of the dynamics of mean fitness in the sink environment? Will the rate of adaptation indeed be independent of the immigration rate? Is there an optimal rate of mutation for adaptation to the sink? Such critical tests of the theory will greatly improve our understanding of adaptation to novel environments. References [1] Lavigne, F., Martin, G., Anciaux, Y., Papaïx, J., and Roques, L. (2019). When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals. bioRxiv, 433235, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/433235 | When sinks become sources: adaptive colonization in asexuals | Florian Lavigne, Guillaume Martin, Yoann Anciaux, Julien Papaïx, Lionel Roques | <p>The successful establishment of a population into a new empty habitat outside of its initial niche is a phenomenon akin to evolutionary rescue in the presence of immigration. It underlies a wide range of processes, such as biological invasions ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology | François Blanquart | 2018-10-03 20:59:16 | View | |

22 Oct 2019

Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frogRudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J. https://doi.org/10.1101/314351Tough as old boots: amphibians from drier habitats are more resistant to desiccation, but less flexible at exploiting wet conditionsRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by Juan Diego Gaitan-Espitia, Jennifer Nicole Lohr and 1 anonymous reviewerSpecies everywhere are facing rapid climatic change, and we are increasingly asking whether populations will adapt, shift, or perish [1]. There is a growing realisation that, despite limited within-population genetic variation, many species exhibit substantial geographic variation in climate-relevant traits. This geographic variation might play an important role in facilitating adaptation to climate change [2,3]. References [1] Hoffmann, A. A., and Sgrò, C. M. (2011). Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature, 470(7335), 479–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09670 | Geographic variation in adult and embryonic desiccation tolerance in a terrestrial-breeding frog | Rudin-Bitterli, T, Evans, J. P. and Mitchell, N. J. | <p>Intra-specific variation in the ability of individuals to tolerate environmental perturbations is often neglected when considering the impacts of climate change. Yet this information is potentially crucial for mitigating any deleterious effects... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Ben Phillips | 2018-05-07 03:35:08 | View | |

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Domesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

03 Jun 2018

Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive conceptThomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet https://doi.org/10.1101/276675Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewer

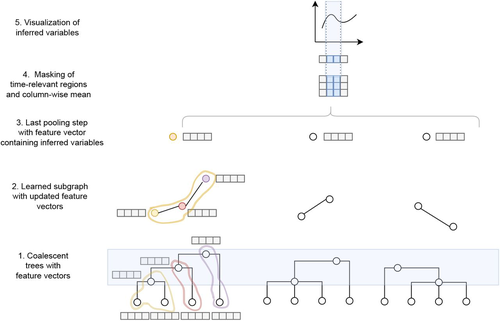

The increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment. In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model. The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies. The authors highlight and explain the following points: Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations. References [1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675 | Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer