Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Oct 2022

Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch.Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414Evolution of sperm morphology in Daphnia within a phyologenetic contextRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Renate Matzke-Karasz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study sperm morphology is studied in 15 Daphnia species and the morphological data are mapped on a Daphnia phylogeny. The authors found that despite the internal fertilization mode, Daphnia have among the smallest sperm recorded, as would be expected with external fertilization. The authors also conclude that increase in sperm length has evolved twice, that sperm encapsulation has been lost in a clade, and that this clade has very polymorphic sperm with long, and often numerous, filopodia. Daphnia is an interesting model to study sperm morphology because the biology of sexual reproduction is often ignored in (cyclical) parthenogenetic species. Daphnia is part of the very diverse and successful group of cladocerans with cyclical parthenogenetic reproduction. The success of this reproduction mode is reflected in the known 620 species that radiated within this order, this is more than half of the known Branchiopod species diversity and the estimated number of cladoceran species is even two to four times higher (Forró et al. 2008). Looking at this particular model with a good phylogeny and some particularity in the mode of fertilization/reproduction, has thus a large value. Most Daphnia species are cyclical parthenogenetic and switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on the environmental conditions. Within the genus Daphnia, evolution to obligate asexuality has evolved in at least four independent occasions by three different mechanisms: (i) obligate parthenogenesis through hybridisation with or without polyploidy, (ii) asexuality has been acquired de novo in some populations and (iii) in certain lineages females reproduce by obligate parthenogenesis, whereas the clonally propagated males produce functional haploid sperm that allows them to breed with sexual females of normal cyclically parthenogenetic lineages (more on this in Decaestecker et al. 2009). This study is made in the context of a body of research on the evolution of one of the most fundamental and taxonomically diverse cell types. There is surprisingly little known about the adaptive value underlying their morphology because it is very difficult to test this experimentally. Studying sperm morphology across species is interesting to study evolution itself because it is a "simple trait". As the authors state: The understanding of the adaptive value of sperm morphology, such as length and shape, remains largely incomplete (Lüpold & Pitnick, 2018). Based on phylogenetic analyses across the animal kingdom, the general rule seems to be that fertilization mode (i.e. whether eggs are fertilized within or outside the female) is a key predictor of sperm length (Kahrl et al., 2021). There is a trade-off between sperm number and length (Immler et al., 2011). This study reports on one of the smallest sperm recorded despite the fertilization being internal. The brood pouch in Daphnia is an interesting particularity as fertilisation occurs internally, but it is not disconnected from the environment. It is also remarkable that there are two independent evolution lines of sperm size in this group. It suggests that those traits have an adaptive value. References Decaestecker E, De Meester L, Mergeay J (2009) Cyclical Parthenogenesis in Daphnia: Sexual Versus Asexual Reproduction. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, Dijk P), pp. 295–316. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_15 Duneau David, Möst M, Ebert D (2022) Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. bioRxiv, 2020.01.31.929414, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929414 Forró L, Korovchinsky NM, Kotov AA, Petrusek A (2008) Global diversity of cladocerans (Cladocera; Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9013-5 Immler S, Pitnick S, Parker GA, Durrant KL, Lüpold S, Calhim S, Birkhead TR (2011) Resolving variation in the reproductive tradeoff between sperm size and number. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5325–5330. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009059108 Kahrl AF, Snook RR, Fitzpatrick JL (2021) Fertilization mode drives sperm length evolution across the animal tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-y Lüpold S, Pitnick S (2018) Sperm form and function: what do we know about the role of sexual selection? Reproduction, 155, R229–R243. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0536 | Evolution of sperm morphology in a crustacean genus with fertilization inside an open brood pouch. | Duneau, David; Moest, Markus; Ebert, Dieter | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sperm is the most fundamental male reproductive feature. It serves the fertilization of eggs and evolves under sexual selection. Two components of sperm are of particular interest, their number and their morphology.... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-05-30 22:54:15 | View | |

10 Nov 2017

POSTPRINT

Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of PlacentalsWu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043A new approach to DNA-aided ancestral trait reconstruction in mammalsRecommended by Nicolas Galtier and Belinda ChangReconstructing ancestral character states is an exciting but difficult problem. The fossil record carries a great deal of information, but it is incomplete and not always easy to connect to data from modern species. Alternatively, ancestral states can be estimated by modelling trait evolution across a phylogeny, and fitting to values observed in extant species. This approach, however, is heavily dependent on the underlying assumptions, and typically results in wide confidence intervals. An alternative approach is to gain information on ancestral character states from DNA sequence data. This can be done directly when the trait of interest is known to be determined by a single, or a small number, of major effect genes. In some of these cases it can even be possible to investigate an ancestral trait of interest by inferring and resurrecting ancestral sequences in the laboratory. Examples where this has been successfully used to address evolutionary questions range from the nocturnality of early mammals [1], to the loss of functional uricases in primates, leading to high rates of gout, obesity and hypertension in present day humans [2]. Another possibility is to rely on correlations between species traits and the genome average substitution rate/process. For instance, it is well established that the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rate, dN/dS, is generally higher in large than in small species of mammals, presumably due to a reduced effective population size in the former. By estimating ancestral dN/dS, one can therefore gain information on ancestral body mass (e.g. [3-4]). The interesting paper by Wu et al. [5] further develops this second possibility of incorporating information on rate variation derived from genomic data in the estimation of ancestral traits. The authors analyse a large set of 1185 genes in 89 species of mammals, without any prior information on gene function. The substitution rate is estimated for each gene and each branch of the mammalian tree, and taken as an indicator of the selective constraint applying to a specific gene in a specific lineage – more constraint, slower evolution. Rate variation is modelled as resulting from a gene effect, a branch effect, and a gene X branch interaction effect, which captures lineage-specific peculiarities in the distribution of functional constraint across genes. The interaction term in terminal branches is regressed to observed trait values, and the relationship is used to predict ancestral traits from interaction terms in internal branches. The power and accuracy of the estimates are convincingly assessed via cross validation. Using this method, the authors were also able to use an unbiased approach to determine which genes were the main contributors to the evolution of the life-history traits they reconstructed. The ancestors to current placental mammals are predicted to have been insectivorous - meaning that the estimated distribution of selective constraint across genes in basal branches of the tree resembles that of extant insectivorous taxa - consistent with the mainstream palaeontological hypothesis. Another interesting result is the prediction that only nocturnal lineages have passed the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, so that the ancestors of current orders of placentals would all have been nocturnal. This suggests that the so-called "nocturnal bottleneck hypothesis" should probably be amended. Similar reconstructions are achieved for seasonality, sociality and monogamy – with variable levels of uncertainty. The beauty of the approach is to analyse the variance, not only the mean, of substitution rate across genes, and their methods allow for the identification of the genes contributing to trait evolution without relying on functional annotations. This paper only analyses discrete traits, but the framework can probably be extended to continuous traits as well. References [1] Bickelmann C, Morrow JM, Du J, Schott RK, van Hazel I, Lim S, Müller J, Chang BSW, 2015. The molecular origin and evolution of dim-light vision in mammals. Evolution 69: 2995-3003. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12794 [2] Kratzer, JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN, Cicerchi C, Graves CL, Tipton PA, Ortlund EA, Johnson RJ, Gaucher EA, 2014. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, USA 111:3763-3768. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320393111 [3] Lartillot N, Delsuc F. 2012. Joint reconstruction of divergence times and life-history evolution in placental mammals using a phylogenetic covariance model. Evolution 66:1773-1787. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01558.x [4] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJ, Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:5-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss211 [5] Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. 2016. Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals. Current Biology 27: 3025-3033. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.043 | Rates of Molecular Evolution Suggest Natural History of Life History Traits and a Post-K-Pg Nocturnal Bottleneck of Placentals | Wu J, Yonezawa T, Kishino H. | Life history and behavioral traits are often difficult to discern from the fossil record, but evolutionary rates of genes and their changes over time can be inferred from extant genomic data. Under the neutral theory, molecular evolutionary rate i... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Life History, Molecular Evolution, Paleontology, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Nicolas Galtier | 2017-11-10 14:52:26 | View | |

16 May 2023

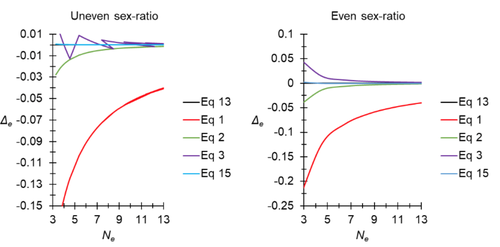

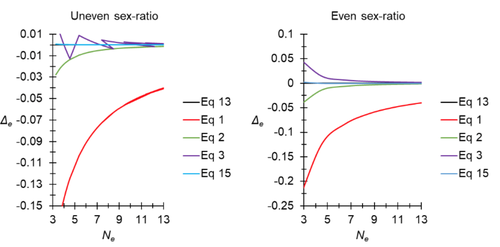

A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofsThierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968All you ever wanted to know about Ne in one handy placeRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by Jesse ("Jay") Taylor and 1 anonymous reviewerOf the four evolutionary forces, three can be straightforwardly summarized both conceptually and mathematically in the context of an allele at a genomic locus. Mutation (the mutation rate, μ) is simply captured by the per-site, per-generation probability that an allele mutates into a different allele. Recombination (the recombination rate, r) is captured as the probability of recombination between two sites, wherein alleles that are in different genomes in one generation come together in the same genome in the next generation. Natural selection (the selection coefficient, s) is captured by the probability that an allele is present in the next generation, relative to some reference. Random genetic drift – the random fluctuation in allele frequency due to sampling in a finite population - is not so straightforwardly summarized. The first, and most common way of characterizing evolutionary dynamics in a finite population is the Wright-Fisher model, in which the only deviation from the assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg conditions is finite population size. Importantly, in a W-F population, mating between diploid individuals is random, which implies self-fertile monoecy, and generations are non-overlapping. In an ideal W-F population, the probability that a gene copy leaves i descendants in the next generation is the result of binomial sampling of uniting gametes (if the locus is biallelic). The – and the next word is meaningful – magnitude/strength/rate/power/amount of genetic drift is proportional to 1/2N, where N is the size of the population. All of the following are affected by genetic drift: (1) the probability that a neutral allele ultimately reaches fixation, (2) the rate of loss of genetic variation within a population, (3) the rate of increase of genetic variance among populations, (4) the amount of genetic variation segregating in a population, (5) the probability of fixation/loss of a weakly selected variant. Presumably no real population adheres to ideal W-F conditions, which leads to the notion of "effective population size", Ne (Wright 1931), loosely defined as "the size of an ideal W-F population that experiences an equivalent strength of genetic drift". Almost always, Ne<N, and any violation of W-F assumptions can affect Ne. Importantly, Ne can be defined in different ways, and the specific formulation of Ne can have different implications for evolution. Ne was initially defined in terms of the rate of decrease of heterozygosity (inbreeding effective size) and increase in variance among populations (variance effective size). Ewens (1979) defined the Eigenvalue effective size (equivalent to the "random extinction" effective size) and elaborated on the conditions under which the various formulations of Ne differ (Ewens 1982). Nordborg and Krone (2002) defined the effective size in terms of the coalescent, and they identified conditions in which genetic drift cannot be described in terms of a W-F model (Sjodin et al. 2005); also see Karasov et al. (2010); Neher and Shraiman (2011). Distinct from the issue of defining Ne is the issue of calculating Ne from data, which is the focus of this paper by De Meeus and Noûs (2023). Pudovkin et al. (1996) showed that the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population can be formulated in terms of excess heterozygosity, which the current authors note is equivalent to formulating Ne in terms of Wright's FIS statistic. As emphasized by the title, the marquee contribution of this paper is to provide a better approximation of the Eigenvalue effective size in a dioecious population. Science marches onward, although the empirical utility of this advance is obviously limited, given the tremendous inherent sources of uncertainty in real-world estimates of Ne. Perhaps more valuable, however, is the extensive set of appendixes, in which detailed derivations are provided for the various formulations of effective size. By way of analogy, the material presented here can be thought of as an extension of the material presented in section 7.6 of Crow and Kimura (1970), in which the Inbreeding and Variance effective population sizes are derived and compared. The appendixes should serve as a handy go-to source of detailed theoretical information with respect to the different formulations of effective population size. REFERENCES Crow, J. F. and M. Kimura. 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ. De Meeûs, T. and Noûs, C. 2023. A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs. Zenodo, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7927968 Ewens, W. J. 1979. Mathematical Population Genetics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Ewens, W. J. 1982. On the concept of the effective population size. Theoretical Population Biology 21:373-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(82)90024-7 Karasov, T., P. W. Messer, and D. A. Petrov. 2010. Evidence that adaptation in Drosophila Is not limited by mutation at single sites. Plos Genetics 6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000924 Neher, R. A. and B. I. Shraiman. 2011. Genetic Draft and Quasi-Neutrality in Large Facultatively Sexual Populations. Genetics 188:975-U370. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.111.128876 Nordborg, M. and S. M. Krone. 2002. Separation of time scales and convergence to the coalescent in structured populations. Pp. 194–232 in M. Slatkin, and M. Veuille, eds. Modern Developments in Theoretical Population Genetics: The Legacy of Gustave Malécot. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~krone/malecot.pdf Pudovkin, A. I., D. V. Zaykin, and D. Hedgecock. 1996. On the potential for estimating the effective number of breeders from heterozygote-excess in progeny. Genetics 144:383-387. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/144.1.383 Sjodin, P., I. Kaj, S. Krone, M. Lascoux, and M. Nordborg. 2005. On the meaning and existence of an effective population size. Genetics 169:1061-1070. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.026799 Wright, S. 1931. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16:0097-0159. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/16.2.97 | A new and almost perfectly accurate approximation of the eigenvalue effective population size of a dioecious population: comparisons with other estimates and detailed proofs | Thierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs | <p>The effective population size is an important concept in population genetics. It corresponds to a measure of the speed at which genetic drift affects a given population. Moreover, this is most of the time the only kind of population size that e... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Charles Baer | 2023-02-22 16:53:49 | View | |

21 Nov 2019

Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticityRobin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous https://doi.org/10.1101/717702Nutrition-dependent effects of gut bacteria on growth plasticity in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well known that the rearing environment has strong effects on life history and fitness traits of organisms. Microbes are part of every environment and as such likely contribute to such environmental effects. Gut bacteria are a special type of microbe that most animals harbor, and as such they are part of most animals’ environment. Such microbial symbionts therefore likely contribute to local adaptation [1]. The main question underlying the laboratory study by Guilhot et al. [2] was: How much do particular gut bacteria affect the organismal phenotype, in terms of life history and larval foraging traits, of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common laboratory model species in biology? References [1] Kawecki, T. J. and Ebert, D. (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7: 1225-1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x | Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticity | Robin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous | <p>Environmentally acquired microbial symbionts could contribute to host adaptation to local conditions like vertically transmitted symbionts do. This scenario necessitates symbionts to have different effects in different environments. We investig... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity, Species interactions | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2019-02-13 15:22:23 | View | |

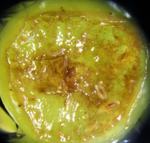

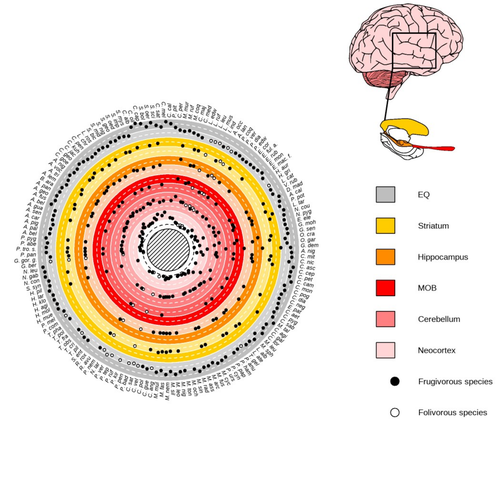

28 Feb 2023

Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architectureBenjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912Macroevolutionary drivers of brain evolution in primatesRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Paula Gonzalez, Orlin Todorov and 3 anonymous reviewersStudying the evolution of animal cognition is challenging because many environmental and species-related factors can be intertwined, which is further complicated when looking at deep-time evolution. Previous knowledge has emphasized the role of intraspecific interactions in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. However, much less is known about such an effect at the interspecific level. Yet, the coexistence of different species in the same geographic area at a given time (sympatry) can impact the evolutionary history of species through character displacement due to biotic interactions. Trait evolution has been observed and tested with morphological external traits but more rarely with brain evolution. Compared to most species’ traits, brain evolution is even more delicate to assess since specific brain regions can be involved in different functions, may they be individual-based and social-based information processing. In a very original and thoroughly executed study, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) addressed the question: How does the co-occurrence of congeneric species shape brain evolution and influence species diversification? By considering brain size as a proxy for cognition, they evaluated whether species sympatry impacted the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates. Fruit resources are hard to find, not continuous through time, heterogeneously distributed across space, but can be predictable. Hence, cognition considerably shapes the foraging strategy and competition for food access can be fierce. Over long timescales, it remains unclear whether brain size and the pace of species diversification are linked in the context of sympatry, and if so how. Recent studies have found that larger brain sizes can be associated with higher diversification rates in birds (Sayol et al. 2019). Similarly, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) thus wondered if the evolution of brain size in primates impacted their dynamic of species diversification, which has been suggested (Melchionna et al. 2020) but not tested. Prior to anything, Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) had to retrace the evolutionary history of sympatry between frugivorous primate lineages through time using the primate tree of life, species’ extant distribution, and process-based models to estimate ancestral range evolution. To infer the effect of species sympatry on the evolution of cognition in frugivorous primates, the authors evaluated the support for phylogenetic models of brain size evolution accounting or not for species sympatry and investigated the directionality of the selection induced by sympatry on brain size evolution. Finally, to better understand the impact of cognition and interactions between primates on their evolutionary success, they tested for correlations between brain size or species’ sympatry and species diversification. Robira & Perez-Lamarque (2023) found that the evolution of the whole brain or brain regions used in immediate information processing was best fitted with models not considering sympatry. By contrast, models considering species sympatry best predicted the evolution of brain regions related to long-term memory of interactions with the socio-ecological environment, with a decrease in their size along with stronger sympatry. Specifically, they found that sympatry was associated with a decrease in the relative size of the hippocampus and striatum, but had no significant effect on the neocortex, cerebellum, or overall brain size. The hippocampus is a brain region that plays a crucial role in processing and memorizing spatiotemporal information, which is relevant for frugivorous primates in their foraging behavior. The study suggests that competition between sympatric species for limited food resources may lead to a more complex and unpredictable food distribution, which may in turn render cognitive foraging not advantageous and result in a selection for smaller brain regions involved in foraging. Niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry may also impact cognitive abilities, with more specialized diets requiring lower cognitive abilities and smaller brain region sizes. On the other hand, the absence of an effect of sympatry on brain regions involved in immediate sensory information processing, such as the cerebellum and neocortex, suggests that foragers do not exploit cues left out by sympatric heterospecific species, or they may discard environmental cues in favor of social cues. This is a remarkable study that highlights the importance of considering the impact of ecological factors, such as sympatry, on the evolution of specific brain regions involved in cognitive processes, and the potential trade-offs in brain region size due to niche partitioning and dietary specialization in sympatry. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms behind these effects and to test for the possible role of social cues in the evolution of brain regions. This study provides insights into the selective pressures that shape brain evolution in primates. References Melchionna M, Mondanaro A, Serio C, Castiglione S, Di Febbraro M, Rook L, Diniz-Filho JAF, Manzi G, Profico A, Sansalone G, Raia P (2020) Macroevolutionary trends of brain mass in Primates. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz161 Robira B, Perez-Lamarque B (2023) Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture. bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.490912, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.490912 Sayol F, Lapiedra O, Ducatez S, Sol D (2019) Larger brains spur species diversification in birds. Evolution, 73, 2085–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13811 | Primate sympatry shapes the evolution of their brain architecture | Benjamin Robira, Benoit Perez-Lamarque | <p style="text-align: justify;">The main hypotheses on the evolution of animal cognition emphasise the role of conspecifics in affecting the socio-ecological environment shaping cognition. Yet, space is often simultaneously occupied by multiple sp... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Fabien Condamine | 2022-05-10 13:43:02 | View | |

25 Feb 2021

Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwigSophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363Assessing the role of host-symbiont interactions in maternal care behaviourRecommended by Trine Bilde based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth, Gabrielle Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

The role of microbial symbionts in governing social traits of their hosts is an exciting and developing research area. Just like symbionts influence host reproductive behaviour and can cause mating incompatibilities to promote symbiont transmission through host populations (Engelstadter and Hurst 2009; Correa and Ballard 2016; Johnson and Foster 2018) (see also discussion on conflict resolution in Johnsen and Foster 2018), microbial symbionts could enhance transmission by promoting the social behaviour of their hosts (Ezenwa et al. 2012; Lewin-Epstein et al. 2017; Gurevich et al. 2020). Here I apply the term ‘symbiosis’ in the broad sense, following De Bary 1879 as “the living together of two differently named organisms“ independent of effects on the organisms involved (De Bary 1879), i.e. the biological interaction between the host and its symbionts may include mutualism, parasitism and commensalism. References Correa, C. C., and Ballard, J. W. O. (2016). Wolbachia associations with insects: winning or losing against a master manipulator. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 153. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00153 De Bary, A. (1879). Die Erscheinung der Symbiose. Verlag von Karl J. Trubner, Strassburg. Engelstädter, J., and Hurst, G. D. (2009). The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 127-149. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120206 Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M., and Xavier, J. B. (2012). Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science, 338(6104), 198-199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412 Gurevich, Y., Lewin-Epstein, O., and Hadany, L. (2020). The evolution of paternal care: a role for microbes?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1808), 20190599. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0599 Hird, S. M. (2017). Evolutionary biology needs wild microbiomes. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 725. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00725 Johnson, K. V. A., and Foster, K. R. (2018). Why does the microbiome affect behaviour?. Nature reviews microbiology, 16(10), 647-655. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3 Kramer et al. (2017). When earwig mothers do not care to share: parent–offspring competition and the evolution of family life. Functional Ecology, 31(11), 2098-2107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12915 Lewin-Epstein, O., Aharonov, R., and Hadany, L. (2017). Microbes can help explain the evolution of host altruism. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14040 Meunier, J., and Kölliker, M. (2012). Parental antagonism and parent–offspring co-adaptation interact to shape family life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1744), 3981-3988. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1416 Meunier, J., Wong, J. W., Gómez, Y., Kuttler, S., Röllin, L., Stucki, D., and Kölliker, M. (2012). One clutch or two clutches? Fitness correlates of coexisting alternative female life-histories in the European earwig. Evolutionary Ecology, 26(3), 669-682. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9510-x Nalepa, C. A. (2020). Origin of mutualism between termites and flagellated gut protists: transition from horizontal to vertical transmission. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00014 Ratz, T., Kramer, J., Veuille, M., and Meunier, J. (2016). The population determines whether and how life-history traits vary between reproductive events in an insect with maternal care. Oecologia, 182(2), 443-452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3685-3 Van Meyel, S., Devers, S., Dupont, S., Dedeine, F. and Meunier, J. (2021) Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig. bioRxiv, 2020.10.08.331363. ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.331363 | Alteration of gut microbiota with a broad-spectrum antibiotic does not impair maternal care in the European earwig | Sophie Van Meyel, Séverine Devers, Simon Dupont, Franck Dedeine and Joël Meunier | <p>The microbes residing within the gut of an animal host often increase their own fitness by modifying their host’s physiological, reproductive, and behavioural functions. Whereas recent studies suggest that they may also shape host sociality and... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2020-10-09 14:07:47 | View | |

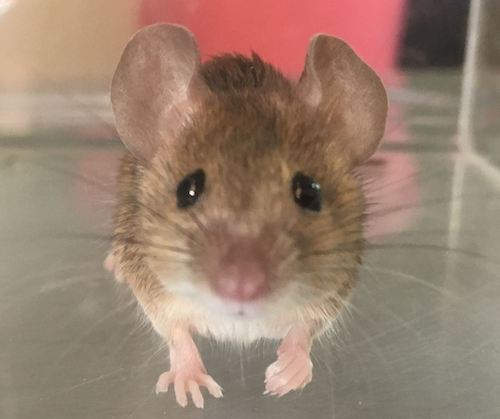

16 Nov 2022

Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in miceCarole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634Tinder in mice: A match made with the sense of smellRecommended by Christelle Fraïsse based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Angeles de Cara, Ludovic Claude Maisonneuve and 1 anonymous reviewer

Differentiation-based genome scans lie at the core of speciation and adaptation genomics research. Dating back to Lewontin & Krakauer (1973), they have become very popular with the advent of genomics to identify genome regions of enhanced differentiation relative to neutral expectations. These regions may represent genetic barriers between divergent lineages and are key for studying reproductive isolation. However, genome scan methods can generate a high rate of false positives, primarily if the neutral population structure is not accounted for (Bierne et al. 2013). Moreover, interpreting genome scans can be challenging in the context of secondary contacts between diverging lineages (Bierne et al. 2011), because the coupling between different components of reproductive isolation (local adaptation, intrinsic incompatibilities, mating preferences, etc.) can occur readily, thus preventing the causes of differentiation from being determined. Smadja and collaborators (2022) applied a sophisticated genome scan for trait association (BAYPASS, Gautier 2015) to underlie the genetic basis of a polygenetic behaviour: assortative mating in hybridizing mice. My interest in this neat study mainly relies on two reasons. First, the authors used an ingenious geographical setting (replicate pairs of “Choosy” versus “Non-Choosy” populations) with multi-way comparisons to narrow down the list of candidate regions resulting from BAYPASS. The latter corrects for population structure, handles cost-effective pool-seq data and allows for gene-based analyses that aggregate SNP signals within a gene. These features reinforce the set of outlier genes detected; however, not all are expected to be associated with mating preference. The second reason why this study is valuable to me is that Smadja et al. (2022) complemented the population genomic approach with functional predictions to validate the genetic signal. In line with previous behavioural and chemical assays on the proximal mechanisms of mating preferences, they identified multiple olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes as highly significant candidates. Therefore, combining genomic signals with functional analyses is a clever way to provide insights into the causes of reproductive isolation, especially when multiple barriers are involved. This is typically true for reinforcement (Butlin & Smadja 2018), suspected to occur in these mice because, in that case, assortative mating (a prezygotic barrier) evolves in response to the cost of hybridization (for example, due to hybrid inviability). As advocated by the authors, their study paves the way for future work addressing the genetic basis of reinforcement, a trait of major evolutionary importance for which we lack empirical data. They also make a compelling case using complementary approaches that olfactory and vomeronasal receptors have a central role in mammal speciation.

Bierne N, Welch J, Loire E, Bonhomme F, David P (2011) The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol Ecol 20: 2044–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x Bierne N, Roze D, Welch JJ (2013) Pervasive selection or is it…? why are FST outliers sometimes so frequent? Mol Ecol 22: 2061–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12241 Butlin RK, Smadja CM (2018) Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. Am Nat 191:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/695136 Gautier M (2015) Genome-Wide Scan for Adaptive Divergence and Association with Population-Specific Covariates. Genetics 201:1555–1579. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.181453 Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/74.1.175 Smadja CM, Loire E, Caminade P, Severac D, Gautier M, Ganem G (2022) Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice. bioRxiv, 2022.07.21.500634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500634 | Divergence of olfactory receptors associated with the evolution of assortative mating and reproductive isolation in mice | Carole M. Smadja, Etienne Loire, Pierre Caminade, Dany Severac, Mathieu Gautier, Guila Ganem | <p>Deciphering the genetic bases of behavioural traits is essential to understanding how they evolve and contribute to adaptation and biological diversification, but it remains a substantial challenge, especially for behavioural traits with polyge... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Speciation | Christelle Fraïsse | 2022-07-25 11:54:52 | View | |

20 Sep 2017

An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in DrosophilaErika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery 10.1101/143560Cancer and loneliness in DrosophilaRecommended by Ana Rivero based on reviews by Ana Rivero and Silvie HuijbenDrosophila flies may not be perceived as a quintessentially social animal, particularly when compared to their eusocial hymenopteran cousins. Although they have no parental care, division of labour or subfertile caste, fruit flies nevertheless exhibit an array of social phenotypes that are potentially comparable to those of their highly social relatives. In the wild, Drosophila adults cluster around food resources where courtship, mating activity and oviposition occur. Recent work has shown not only that social interactions in these clusters condition many aspects of the behaviour and physiology of the flies [1] but also, and perhaps more unexpectedly, that social isolation has a negative impact on their fitness [2]. Many studies in humans point to the role of social isolation as a source of stress that can induce and accelerate disease progression. The ultimate proof of the connection between social interaction and disease is however mired in confounding variables and alternative explanations so the subject, though crucial, remains controversial. With a series of elegant experiments using Drosophila flies that develop an inducible form of intestinal cancer, Dawson et al [3] show that cancer progresses more rapidly in flies maintained in isolation than in flies maintained with other cancerous flies. Further, cancerous flies kept with non-cancerous flies, fare just as badly as when kept alone. Their experiments suggest that this is due to the combined effect of healthy flies avoiding contact with cancerous flies (even though this is a non-contagious disease), and of cancerous flies having higher quality interactions with other cancerous flies than with healthy ones. Perceived isolation is therefore as pernicious as real isolation when it comes to cancer progression in these flies. Like all good research, this study opens up as many questions as it answers, in particular the why and wherefores of the flies’ extraordinary social behaviour in the face of disease. References [1] Camiletti AL and Thompson GJ. 2016. Drosophila as a genetically tractable model for social insect behavior. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 40. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00040 [2] Ruan H and Wu C-F. 2008. Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105: 7506-7510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711127105 [3] Dawson E, Bailly T, Dos Santos J, Moreno C, Devilliers M, Maroni B, Sueur C, Casali A, Ujvari B, Thomas F, Montagne J, Mery F. 2017. An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila. BiorXiv, 143560, ver. 3 of 19th September 2017. doi: 10.1101/143560 | An interaction between cancer progression and social environment in Drosophila | Erika H. Dawson, Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Julie Dos Santos , Céline Moreno, Maëlle Devilliers, Brigitte Maroni, Cédric Sueur, Andreu Casali, Beata Ujvari, Frederic Thomas, Jacques Montagne, Frederic Mery | The ecological benefits of sociality in gregarious species are widely acknowledged. However, only limited data is available on how the social environment influences non-communicable disease outcomes. For instance, despite extensive research over t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Ana Rivero | 2017-05-30 08:55:16 | View | |

03 Apr 2017

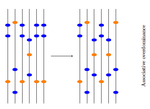

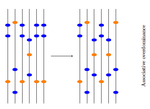

Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous EnvironmentsRomain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/100743Experimental test of the conditions of maintenance of polymorphism under hard and soft selectionRecommended by Stephanie Bedhomme based on reviews by Joachim Hermisson and 2 anonymous reviewers

Theoretical work, initiated by Levene (1953) [1] and Dempster (1955) [2], suggests that within a given environment, the way populations are regulated and contribute to the next generation is a key factor for the maintenance of local adaptation polymorphism. In this theoretical context, hard selection describes the situation where the genetic composition of each population affects its contribution to the next generation whereas soft selection describes the case where the contribution of each population is fixed, whatever its genetic composition. Soft selection is able to maintain polymorphism, whereas hard selection invariably leads to the fixation of one of the alleles. Although the specific conditions (e.g. of migration between populations or drift level) in which this prediction holds have been studied in details by theoreticians, experimental tests have mainly failed, usually leading to the conclusion that the allele frequency dynamics was driven by other mechanisms in the experimental systems and conditions used. Gallet, Froissart and Ravigné [3] have set up a bacterial experimental system which allowed them to convincingly demonstrate that soft selection generates the conditions for polymorphism maintenance when hard selection does not, everything else being equal. The key ingredients of their experimental system are (1) the possibility to accurately produce hard and soft selection regimes when daily transferring the populations and (2) the ability to establish artificial well-characterized reproducible trade-offs. To do so, they used two genotypes resisting each one to one antibiotic and combined, across habitats, low antibiotic doses and difference in medium productivity. The experimental approach contains two complementary parts: the first one is looking at changes in the frequencies of two genotypes, initially introduced at around 50% each, over a small number of generations (ca 40) in different environments and selection regimes (soft/hard) and the second one is convincingly showing polymorphism protection by establishing that in soft selection regimes, the lowest fitness genotype is not eliminated even when introduced at low frequency. In this manuscript, a key point is the dialog between theoretical and experimental approaches. The experiments have been thought and designed to be as close as possible to the situations analysed in theoretical work. For example, the experimental polymorphism protection test (experiment 2) closely matches the equivalent analysis classically performed in theoretical approaches. This close fit between theory and experiment is clearly a strength of this study. This said, the experimental system allowing them to realise this close match also has some limitations. For example, changes in allele frequencies could only be monitored over a quite low number of generations because a longer time-scale would have allowed the contribution of de novo mutations and the likely emergence of a generalist genotype resisting to both antibiotics used to generate the local adaptation trade-offs. These limitations, as well as the actual significance of the experimental tests, are discussed in deep details in the manuscript. References [1] Levene H. 1953. Genetic equilibrium when more than one niche is available. American Naturalist 87: 331–333. doi: 10.1086/281792 [2] Dempster ER. 1955. Maintenance of genetic heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 20: 25–32. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1955.020.01.005 [3] Gallet R, Froissart R, Ravigné V. 2017. Things softly attained are long retained: dissecting the impacts of selection regimes on polymorphism maintenance in experimental spatially heterogeneous environments. bioRxiv 100743; doi: 10.1101/100743 | Things softly attained are long retained: Dissecting the Impacts of Selection Regimes on Polymorphism Maintenance in Experimental Spatially Heterogeneous Environments | Romain Gallet, Rémy Froissart, Virginie Ravigné | <p>Predicting and managing contemporary adaption requires a proper understanding of the determinants of genetic variation. Spatial heterogeneity of the environment may stably maintain polymorphism when habitat contribution to the next generation c... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory | Stephanie Bedhomme | 2017-01-17 11:06:21 | View | |

18 Jun 2020

Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in betweenFanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490Molecular evolution through the joint lens of genomic and population processes.Recommended by Guillaume Achaz based on reviews by Benoit Nabholz and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their perspective article, F Pouyet and KJ Gilbert (2020), propose an interesting overview of all the processes that sculpt patterns of molecular evolution. This well documented article covers most (if not all) important facets of the recurrent debate that has marked the history of molecular evolution: the relative importance of natural selection and neutral processes (i.e. genetic drift). I particularly enjoyed reading this review, that instead of taking a clear position on the debate, catalogs patiently every pieces of information that can help understand how patterns we observed at the genome level, can be understood from a selectionnist point of view, from a neutralist one, and, to quote their title, from "everything in between". The review covers the classical objects of interest in population genetics (genetic drift, selection, demography and structure) but also describes several genomic processes (meiotic drive, linked selection, gene conversion and mutation processes) that obscure the interpretation of these population processes. The interplay between all these processes is very complex (to say the least) and have resulted in many cases in profound confusions while analyzing data. It is always very hard to fully acknowledge our ignorance and we have many times payed the price of model misspecifications. This review has the grand merit to improve our awareness in many directions. Being able to cover so many aspects of a wide topic, while expressing them simply and clearly, connecting concepts and observations from distant fields, is an amazing "tour de force". I believe this article constitutes an excellent up-to-date introduction to the questions and problems at stake in the field of molecular evolution and will certainly also help established researchers by providing them a stimulating overview supported with many relevant references. References [1] Pouyet F, Gilbert KJ (2020) Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between. arXiv:1909.11490 [q-bio]. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. url:https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11490 | Towards an improved understanding of molecular evolution: the relative roles of selection, drift, and everything in between | Fanny Pouyet and Kimberly J. Gilbert | <p>A major goal of molecular evolutionary biology is to identify loci or regions of the genome under selection versus those evolving in a neutral manner. Correct identification allows accurate inference of the evolutionary process and thus compreh... |  | Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Guillaume Achaz | 2019-09-26 10:58:10 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer