Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Sep 2022

Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effectsHelene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784Spreading the risk of reproductive failure when the environment is unpredictable and ephemeralRecommended by Gabriele Sorci based on reviews by Thomas Haaland and Zoltan RadaiMany species breed in environments that are unpredictable, for instance in terms of the availability of resources needed to raise the offspring. Organisms might respond to such spatial and temporal unpredictability by adopting plastic responses to adjust their reproductive investment according to perceived cues of environmental quality. Some species such as the amphibians might also face the problem of ephemeral habitats, when the ponds where they breed have a chance of drying up before metamorphosis has occurred. In this case, maximizing long-term fitness might involve a strategy of spreading the risk, even though the reproductive success of a single reproductive bout might be lower. Understanding how animals (and plants) get adapted to stochastic environments is particularly crucial in the current context of rapid environmental changes. In this article, Jourdan-Pineau et al. report the results of field surveys of the Parsley Frog (Pelodytes punctatus) in Southern France. This frog has peculiar breeding phenology with females breeding in autumn and spring. The authors provide quite an extensive amount of information on the reproductive success of eggs laid in each season and the possible ecological factors accounting for differences between seasons. Although the presence of interspecific competitors and predators does not seem to account for pond-specific reproductive success, the survival of tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in spring is severely impaired when tadpoles from the autumn cohort have managed to survive. This intraspecific competition takes the form of a “priority” effect where tadpoles from the autumn cohort outcompete the smaller larvae from the spring cohort. Given this strong priority effect, one might tentatively predict that females laying in spring should avoid ponds with tadpoles from the autumn cohort. Surprisingly, however, the authors did not find any evidence for such avoidance, which might indicate strong constraints on the availability of ponds where females might possibly lay. Assuming that each female can indeed lay both in autumn and spring, how is this bimodal phenology maintained? Would not be worthier to allocate all the eggs to the autumn (or the spring) laying season? Eggs laid in autumn and spring have to face different environmental hazards, reducing their hatching success and the probability to produce metamorphs (for instance, tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in autumn have to overwinter which might be a particularly risky phase). Jourdan-Pineau and coworkers addressed this question by adapting a bet-hedging model that was initially developed to investigate the strategy of allocation into seed dormancy of annual plants (Cohen 1966) to the case of the bimodal phenology of the Parsley Frog. By feeding the model with the parameter values obtained from the field surveys, they found that the two breeding strategies (laying in autumn and in spring) can coexist as long as the probability of breeding success in the autumn cohort is between 20% and 80% (the range of values allowing the coexistence of a bimodal phenology shrinking a little bit when considering that frogs can reproduce 5 times during their lifespan instead of three times). This paper provides a very nice illustration of the importance of combining approaches (here field monitoring to gather data that can be used to feed models) to understand the evolution of peculiar breeding strategies. Although future work should attempt to gather individual-based data (in addition to population data), this work shows that spreading the risk can be an adaptive strategy in environments characterized by strong stochastic variation. References Cohen D (1966) Optimizing reproduction in a randomly varying environment. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 12, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90188-3 Jourdan-Pineau H., Crochet P.-A., David P. (2022) Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects. bioRxiv, 2022.02.24.481784, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784 | Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects | Helene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">When environmental conditions are unpredictable, expressing alternative phenotypes spreads the risk of failure, a mixed strategy called bet-hedging. In the southern part of its range, the Parsley Frog <em>Pelodytes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Gabriele Sorci | 2022-02-28 11:53:00 | View | |

05 Oct 2022

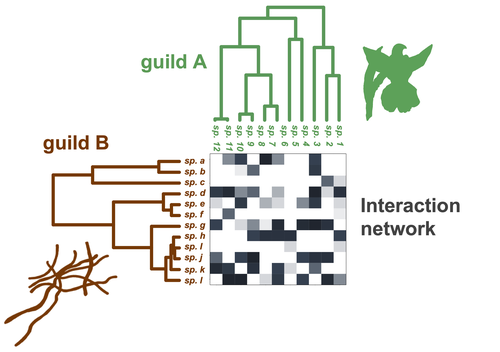

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networksBenoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networksRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720 Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157 Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192 | Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks | Benoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether interactions between species are conserved on evolutionary time-scales has spurred the development of both correlative and process-based approaches for testing phylogenetic signal in interspecific interactio... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2022-03-10 13:48:15 | View | |

20 Nov 2023

Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergenceFrançois Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.28.493856Phenotypic stasis despite genetic divergence and differentiation in Caenorhabditis elegans.Recommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Benoit Pujol and Pedro Simões

Explaining long periods of evolutionary stasis, the absence of change in trait means over geological times, despite the existence of abundant genetic variation in most traits has challenged evolutionary theory since Darwin's theory of evolution by gradual modification (Estes & Arnold 2007). Stasis observed in contemporary populations is even more daunting since ample genetic variation is usually coupled with the detection of selection differentials (Kruuk et al. 2002, Morrissey et al. 2010). Moreover, rapid adaptation to environmental changes in contemporary populations, fuelled by standing genetic variation provides evidence that populations can quickly respond to an adaptive challenge. Explanations for evolutionary stasis usually invoke stabilizing selection as a main actor, whereby optimal trait values remain roughly constant over long periods of time despite small-scale environmental fluctuations. Genetic correlation among traits may also play a significant role in constraining evolutionary changes over long timescales (Schluter 1996). Yet, genetic constraints are rarely so strong as to completely annihilate genetic changes, and they may evolve. Patterns of genetic correlations among traits, as captured in estimates of the G-matrix of additive genetic co-variation, are subject to changes over generations under the action of drift, migration, or selection, among other causes (Arnold et al. 2008). Therefore, under the assumption of stabilizing selection on a set of traits, phenotypic stasis and genetic divergence in patterns of trait correlations may both be observed when selection on trait correlations is weak relative to its effect on trait means. Mallard et al. (2023) set out to test whether selection or drift may explain the divergence in genetic correlation among traits in experimental lines of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and whether stabilizing selection may be a driver of phenotypic stasis. To do so, they analyzed the evolution of locomotion behavior traits over 100 generations of lab evolution in a constant and homogeneous environment after 140 generations of domestication from a largely differentiated set of founder populations. The locomotion traits were transition rates between movement states and direction (still, forward or backward movement). They could estimate the traits' broad-sense G-matrix in three populations at two generations (50 and 100), and in the ancestral mixed population. Similarly, they estimated the shape of the selection surface by regressing locomotion behavior on fertility. Armed with both G-matrix and surface estimates, they could test whether the G's orientation matched selection's orientation and whether changes in G were constrained by selection. They found stasis in trait mean over 100 generations but divergence in the amount and orientation of the genetic variation of the traits relative to the ancestral population. The selected populations changed orientation of their G-matrices and lost genetic variation during the experiment in agreement with a model of genetic drift on quantitative traits. Their estimates of selection also point to mostly stabilizing selection on trait combinations with weak evidence of disruptive selection, suggesting a saddle-shaped selection surface. The evolutionary responses of the experimental populations were mostly consistent with small differentiation in the shape of G-matrices during the 100 generations of stabilizing selection. Mallard et al. (2023) conclude that phenotypic stasis was maintained by stabilizing selection and drift in their experiment. They argue that their findings are consistent with a "table-top mountain" model of stabilizing selection, whereby the population is allowed some wiggle room around the trait optimum, leaving space for random fluctuations of trait variation, and especially trait co-variation. The model is an interesting solution that might explain how stasis can be maintained over contemporary times while allowing for random differentiation of trait genetic co-variation. Whether such differentiation can then lead to future evolutionary divergence once replicated populations adapt to a new environment is an interesting idea to follow. References Arnold, S. J., Bürger, R., Hohenlohe, P. A., Ajie, B. C. and Jones, A. G. 2008. Understanding the evolution and stability of the G-matrix. Evolution 62(10): 2451-2461. | Phenotypic stasis with genetic divergence | François Mallard, Luke Noble, Thiago Guzella, Bruno Afonso, Charles F. Baer, Henrique Teotónio | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether or not genetic divergence in the short-term of tens to hundreds of generations is compatible with phenotypic stasis remains a relatively unexplored problem. We evolved predominantly outcrossing, genetically ... | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Experimental Evolution, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | 2022-09-01 14:32:53 | View | ||

26 Oct 2021

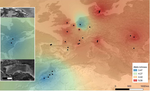

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerEach individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

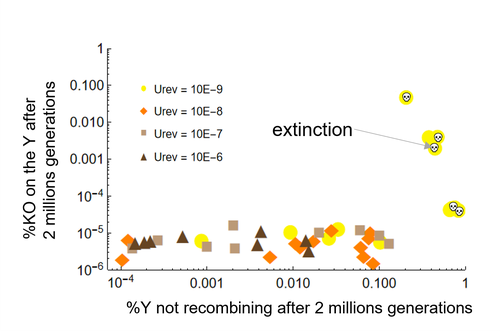

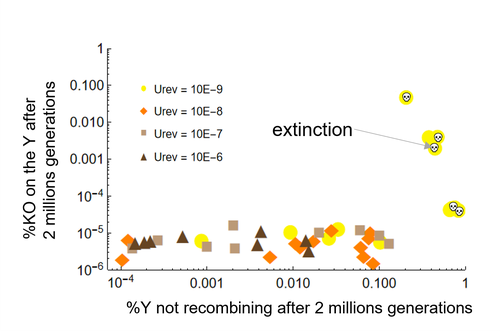

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View | |

30 Oct 2023

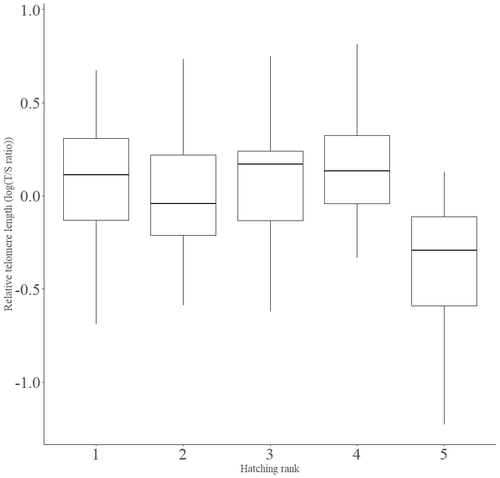

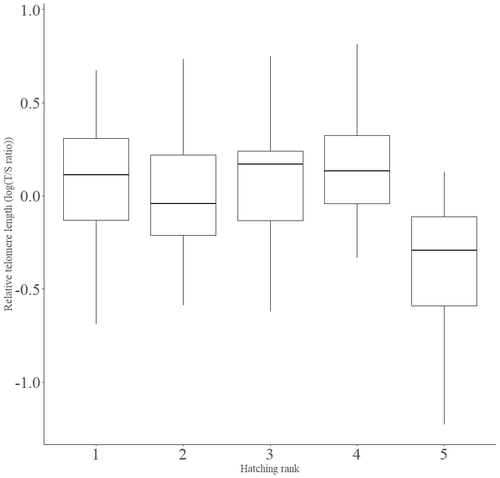

Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, Athene noctuaFrançois Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu https://doi.org/10.32942/X2BS3SDeciphering the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlingsRecommended by Jean-François Lemaitre based on reviews by Florentin Remot and 1 anonymous reviewerThe search for physiological markers of health and survival in wild animal populations is attracting a great deal of interest. At present, there is no (and may never be) consensus on such a single, robust marker but of all the proposed physiological markers, telomere length is undoubtedly the most widely studied in the field of evolutionary ecology (Monaghan et al., 2022). Broadly speaking, telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of chromosomes in eukaryotes, protecting genomic DNA against oxidative stress and various detrimental processes (e.g. DNA end-joining) and thus maintaining genome stability (Blackburn et al., 2015). However, in most somatic cells from the vast majority of the species, telomere sequences are not replicated and telomere length progressively declines with increased age (Remot et al., 2022). This shortening of telomere length upon a critical level is causally linked to cellular senescence and has been invoked as one of the primary causes of the aging process (López-Otín et al., 2023). Studies performed in both captive and wild populations of animals have further demonstrated that short telomeres (or telomere sequences with a fast attrition rate) are to some extent associated with an increased risk of mortality, even if the magnitude of this association largely differs between species and populations (Wilbourn et al., 2018). The repeated observations of associations between telomere length and mortality risk have called for studies seeking to identify the ecological and biological factors that – beyond chronological age – shape the between-individual variability in telomere length. A wide spectrum of environmental stressors such as the level of exposure to pathogens or the degree of human disturbances has been proposed as possible modulators of telomere dynamics (see Chatelain et al., 2019). However, within species, the relative contribution of various ecological and biological factors on telomere length has been rarely quantified. In that context, the study of Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) constitutes a timely attempt to decipher the relative contribution of environmental and biological factors driving telomere length in nestlings (i.e. when individuals are between 15 and 35 days of age) from a wild population of little owls, Athene noctua. In addition to chronological age, Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) analysed the effects of two environmental variables (i.e. cohort and habitat quality) as well as three life history traits (i.e. hatching rank, sex and body condition). Among these traits, sex was found to impact nestling’s telomere length with females carrying longer telomeres than males. Traditionally, the among-individuals variability in telomere length during the juvenile period is interpreted as a direct consequence of differences in growth allocation. Fast-growing individuals are typically supposed to undergo more cell divisions and a higher exposure to oxidative stress, which ultimately shortens telomeres (Monaghan & Ozanne, 2018). Whether - despite a slightly female-biased sexual size dimorphism - male little owls display a condensed period of fast growth that could explain their shorter telomere is yet to be determined. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these sex differences in telomere length in terms of mortality risk. In birds, it has been observed that telomere length during early life can predict lifespan (see Heidinger et al., 2012 in zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata), suggesting that females little owls might live longer than their conspecific males. Yet, adult mortality is generally female-biased in birds (Liker & Székely, 2005) and whether little owls constitute an exception to this rule - possibly mediated by sex-specific telomere dynamics - remains to be explored. Quite surprisingly, the present study in little owls did not evidence any clear effect of environmental conditions on nestling’s telomere length, at both temporal and special scales. While a trend for a temporal effect was detected with telomere length being slightly shorter for nestling born the last year of the study (out of 4 years analysed), habitat quality (measured by the proportion of meadow and orchards in the nest environment) had absolutely no impact on nestling telomere length. Recently published studies in wild populations of vertebrates have highlighted the detrimental effects of harsh environmental conditions on telomere length (e.g. Dupoué et al., 2022 in common lizards, Zootoca vivipara), arguing for a key role of telomere dynamics in the emerging field of conservation physiology. While we can recognize the relevance of such an integrative approach, especially in the current context of climate change, the study by Criscuolo and colleagues (2023) reminds us that the relationships between environmental conditions and telomere dynamics are far from straightforward. Depending on the species and its life history, telomere length in early life could indeed capture very different environmental signals. References Blackburn, E. H., Epel, E. S., & Lin, J. (2015). Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science, 350(6265), 1193-1198. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3389 | Telomere length vary with sex, hatching rank and year of birth in little owls, *Athene noctua* | François Criscuolo, Inès Fache, Bertrand Scaar, Sandrine Zahn, Josefa Bleu | <p>Telomeres are non-coding DNA sequences located at the end of linear chromosomes, protecting genome integrity. In numerous taxa, telomeres shorten with age and telomere length (TL) is positively correlated with longevity. Moreover, TL is also af... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Jean-François Lemaitre | 2023-03-07 09:44:32 | View | |

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

08 Feb 2019

Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenesAnouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo https://doi.org/10.1101/337477E5, the third oncogene of PapillomavirusRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Leonardo de Oliveira Martins and 1 anonymous reviewerPapillomaviruses (PVs) infect almost all mammals and possibly amniotes and bony fishes. While most of them have no significant effects on the hosts, some induce physical lesions. Phylogeny of PVs consists of a few crown groups [1], among which AlphaPVs that infect primates including human have been well studied. They are associated to largely different clinical manifestations: non-oncogenic PVs causing anogenital warts, oncogenic and non-oncogenic PVs causing mucosal lesions, and non-oncogenic PVs causing cutaneous warts. References [1] Bravo, I. G., & Alonso, Á. (2004). Mucosal human papillomaviruses encode four different E5 proteins whose chemistry and phylogeny correlate with malignant or benign growth. Journal of virology, 78, 13613-13626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13613-13626.2004 | Genome plasticity in Papillomaviruses and de novo emergence of E5 oncogenes | Anouk Willemsen, Marta Félez-Sánchez, and Ignacio G. Bravo | <p>The clinical presentations of papillomavirus (PV) infections come in many different flavors. While most PVs are part of a healthy skin microbiota and are not associated to physical lesions, other PVs cause benign lesions, and only a handful of ... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Hirohisa Kishino | 2018-06-04 16:15:39 | View | |

02 Jan 2019

Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by EricaMichael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt https://doi.org/10.1101/290791The colonization history of largely isolated habitatsRecommended by Andrea S. Meseguer based on reviews by Simon Joly, Florian Boucher and 2 anonymous reviewersThe build-up of biodiversity is the result of in situ speciation and immigration, with the interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability determining the probability of an organism to establish in a new area. The relative contribution of these factors have long interested biogeographers, in particular to explain the distribution of organisms adapted to habitats that remained largely isolated, such as the colonization of oceanic islands or land waters. The focus of this study is the formation of the afrotemperate flora; patches of temperate vegetation separated by thousands of kilometers in Africa, with high levels of endemism described in the Cape region, the Drakensberg range and the high mountains of tropical east Africa [1]. The floristic affinities between these centers of endemism have frequently been explored but the origin of many afrotemperate lineages remains enigmatic [2]. References [1] Linder, H.P. 1990. On the relationship between the vegetation and floras of the Afromontane and the Cape regions of Africa. Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Allgemeine Botanik Hamburg 23b:777–790. | Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica | Michael D. Pirie, Martha Kandziora, Nicolai M. Nuerk, Nicholas C. Le Maitre, Ana Laura Mugrabi de Kuppler, Berit Gehrke, Edward G.H. Oliver, and Dirk U. Bellstedt | <p>The coincidence of long distance dispersal and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors o... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography | Andrea S. Meseguer | 2018-04-09 10:10:04 | View | |

03 Jun 2018

Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive conceptThomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet https://doi.org/10.1101/276675Let’s move beyond costs of resistance!Recommended by Inês Fragata and Claudia Bank based on reviews by Danna Gifford, Helen Alexander and 1 anonymous reviewerThe increase in the prevalence of (antibiotic) resistance has become a major global health concern and is an excellent example of the impact of real-time evolution on human society. This has led to a boom of studies that investigate the mechanisms and factors involved in the evolution of resistance, and to the spread of the concept of "costs of resistance". This concept refers to the relative fitness disadvantage of a drug-resistant genotype compared to a non-resistant reference genotype in the ancestral (untreated) environment. In their paper, Lenormand et al. [1] discuss the history of this concept and highlight its caveats and limitations. The authors address both practical and theoretical problems that arise from the simplistic view of "costly resistance" and argue that they can be prejudicial for antibiotic resistance studies. For a better understanding, they visualize their points of critique by means of Fisher's Geometric model. The authors give an interesting historical overview of how the concept arose and speculate that it emerged (during the 1980s) in an attempt by ecologists to spread awareness that fitness can be environment-dependent, and because of the concept's parallels to trade-offs in life-history evolution. They then identify several problems that arise from the concept, which, besides the conceptual misunderstandings that they can cause, are important to keep in mind when designing experimental studies. The authors highlight and explain the following points: Lenormand et al.'s paper [1] is a timely perspective piece in light of the ever-increasing efforts to understand and tackle resistance evolution [2]. Although some readers may shy away from the rather theoretical presentation of the different points of concern, it will be useful for both theoretical and empirical readers by illustrating the misconceptions that can arise from the concept of the cost of resistance. Ultimately, the main lesson to be learned from this paper may not be to ban the term "cost of resistance" from one's vocabulary, but rather to realize that the successful fight against drug resistance requires more differential information than the measurement of fitness effects in a drug-treated vs. non-treated environment in the lab [3-4]. Specifically, a better integration of the ecological aspects of drug resistance evolution and maintenance is needed [5], and we are far from a general understanding of how environmental factors interact and influence an organism's (absolute and relative) fitness and the effect of resistance mutations. References [1] Lenormand T, Harmand N, Gallet R. 2018. Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept. bioRxiv 276675, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/276675 | Cost of resistance: an unreasonably expensive concept | Thomas Lenormand, Noemie Harmand, Romain Gallet | <p>The cost of resistance, or the fitness effect of resistance mutation in absence of the drug, is a very widepsread concept in evolutionary genetics and beyond. It has represented an important addition to the simplistic view that resistance mutat... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Experimental Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Population Genetics / Genomics | Inês Fragata | 2018-03-09 02:22:07 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer