Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 Feb 2024

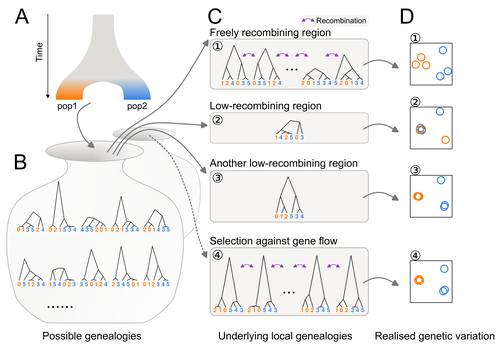

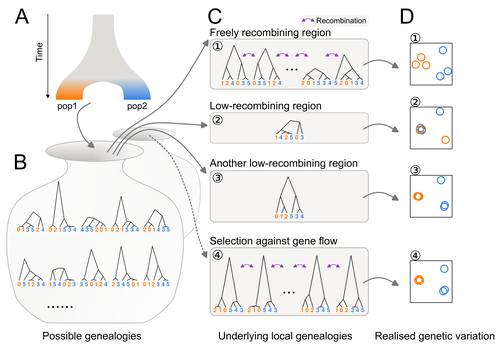

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

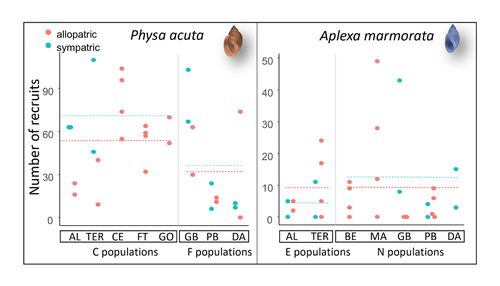

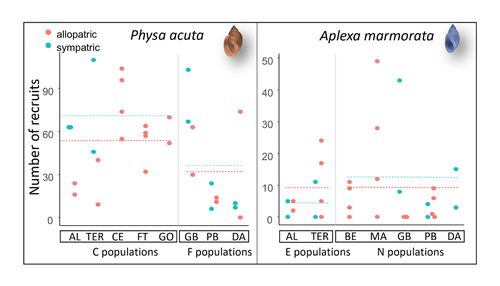

Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident speciesElodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987The evolution of a hobo snailRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewersAt the very end of a paper entitled "Copepodology for the ornithologist" Hutchinson (1951) pointed out the possibility of 'fugitive species'. A fugitive species, said Hutchinson, is one that we would typically think of as competitively inferior. Wherever it happens to live it will eventually be overwhelmed by competition from another species. We would expect it to rapidly go extinct but for one reason: it happens to be a much better coloniser than the other species. Now all we need to explain its persistence is a dose of space and a little disturbance: a world in which there are occasional disturbances that cause local extinction of the dominant species. Now, argued Hutchinson, we have a recipe for persistence, albeit of a harried kind. As Hutchinson put it, fugitive species "are forever on the move, always becoming extinct in one locality as they succumb to competition, and always surviving as they reestablish themselves in some other locality." It is a fascinating idea, not just because it points to an interesting strategy, but also because it enriches our idea of competition: competition for space can be just as important as competition for time. Hutchinson's idea was independently discovered with the advent of metapopulation theory (Levins 1971; Slatkin 1974) and since then, of course, ecologists have gone looking, and they have unearthed many examples of species that could be said to have a fugitive lifestyle. These fugitive species are out there, but we don't often get to see them evolve. In their recent paper, Chapuis et al. (2024) make a convincing case that they have seen the evolution of a fugitive species. They catalog the arrival of an invasive freshwater snail on Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, and they wonder what impact this snail's arrival might have on a native freshwater snail. This is a snail invasion, so it has been proceeding at a majestic pace, allowing the researchers to compare populations of the native snail that are completely naive to the invader with those that have been exposed to the invader for either a relatively short period (<20 generations) or longer periods (>20 generations). They undertook an extensive set of competition assays on these snails to find out which species were competitively superior and how the native species' competitive ability has evolved over time. Against naive populations of the native, the invasive snail turns out to be unequivocally the stronger competitor. (This makes sense; it probably wouldn't have been able to invade if it wasn't.) So what about populations of the native snail that have been exposed for longer, that have had time to adapt? Surprisingly these populations appear to have evolved to become even weaker competitors than they already were. So why is it that the native species has not simply been driven extinct? Drawing on their previous work on this system, the authors can explain this situation. The native species appears to be the better coloniser of new habitats. Thus, it appears that the arrival of the invasive species has pushed the native species into a different place along the competition-colonisation axis. It has sacrificed competitive ability in favour of becoming a better coloniser; it has become a fugitive species in its own backyard. This is a really nice empirical study. It is a large lab study, but one that makes careful sampling around a dynamic field situation. Thus, it is a lab study that informs an earlier body of fieldwork and so reveals a fascinating story about what is happening in the field. We are left not only with a particularly compelling example of character displacement towards a colonising phenotype but also with something a little less scientific: the image of a hobo snail, forever on the run, surviving in the spaces in between. References Chapuis E, Jarne P, David P (2024) Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species. bioRxiv, 2023.10.25.563987, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987 Hutchinson, G.E. (1951) Copepodology for the Ornithologist. Ecology 32: 571–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1931746 Levins, R., and D. Culver. (1971) Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, no. 6: 1246–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246. Slatkin, Montgomery. (1974) Competition and Regional Coexistence. Ecology 55, no. 1: 128–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934625. | Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species | Elodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">Biological invasions by phylogenetically and ecologically similar competitors pose an evolutionary challenge to native species. Cases of character displacement following invasions suggest that they can respond to th... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Species interactions | Ben Phillips | 2023-10-26 15:49:33 | View | |

06 Feb 2024

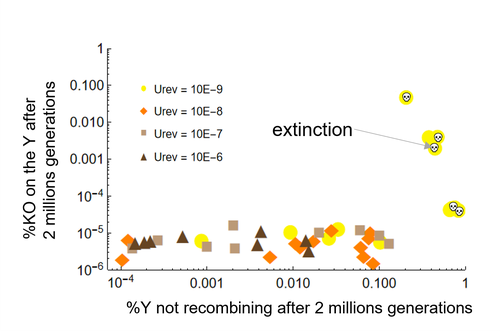

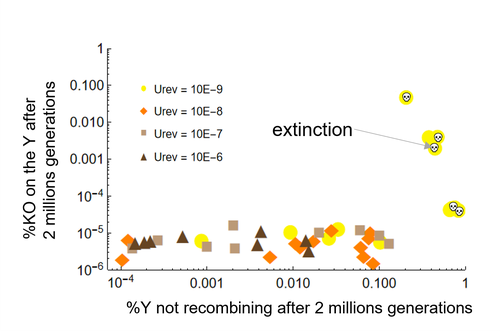

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View | |

21 Feb 2023

Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugsJonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778Nutritional symbioses in triatomines: who is playing?Recommended by Natacha Kremer based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and Olivier DuronNearly 8 million people are suffering from Chagas disease in the Americas. The etiological agent, Trypanosoma cruzi, is mainly transmitted by triatomine bugs, also known as kissing or vampire bugs, which suck blood and transmit the parasite through their feces. Among these triatomine species, Rhodnius prolixus is considered the main vector, and many studies have focused on characterizing its biology, physiology, ecology and evolution. Interestingly, given that Rhodnius species feed almost exclusively on blood, their diet is unbalanced, and the insects can lack nutrients and vitamins that they cannot synthetize themself, such as B-vitamins. In all insects feeding exclusively on blood, symbioses with microbes producing B-vitamins (mainly biotin, riboflavin and folate) have been widely described (see review in Duron and Gottlieb 2020) and are critical for insect development and reproduction. These co-evolved relationships between blood feeders and nutritional symbionts could now be considered to develop new control methods, by targeting the ‘Achille’s heel’ of the symbiotic association (i.e., transfer of nutrient and / or control of nutritional symbiont density). But for this, it is necessary to better characterize the relationships between triatomines and their symbionts. R. prolixus is known to be associated with several symbionts. The extracellular gut symbiont Rhodococcus rhodnii, which reaches high bacterial densities and is almost fixed in R. prolixus populations, appears to be a nutritional symbiont under many blood sources. This symbiont can provide B-vitamins such as biotin (B7), niacin (B3), thiamin (B1), pyridoxin (B6) or riboflavin (B2) and can play an important role in the development and the reproduction of R. prolixus (Pachebat et al. (2013) and see review in Salcedo-Porras et al. (2020)). This symbiont is orally acquired through egg smearing, ensuring the fidelity of transmission of the symbiont from mother to offspring. However, as recently highlighted by Tobias et al. (2020) and Gilliland et al. (2022), other gut microbes could also participate to the provision of B-vitamins, and R. rhodnii could additionally provide metabolites (other than B-vitamins) increasing bug fitness. In the study from Filée et al., the authors focused on Wolbachia, an intracellular, maternally inherited bacterium, known to be a nutritional symbiont in other blood-sucking insects such as bedbugs (Nikoh et al. 2014), and its potential role in vitamin provision in triatomine bugs. After screening 17 different triatomine species from the 3 phylogenetic groups prolixus, pallescens and pictipes, they first show that Wolbachia symbionts are widely distributed in the different Rhodnius species. Contrary to R. rhodnii that were detected in all samples, Wolbachia prevalence was patchy and rarely fixed. The authors then sequenced, assembled, and compared 13 Wolbachia genomes from the infected Rhodnius species. They showed that all Wolbachia are phylogenetically positioned in the supergroup F that contains wCle (the Wolbachia from bedbugs). In addition, 8 Wolbachia strains (out of 12) encode a biotin operon under strong purifying selection, suggesting the preservation of the biological function and the metabolic potential of Wolbachia to supplement biotin in their Rhodnius host. From the study of insect genomes, the authors also evidenced several horizontal transfers of genes from Wolbachia to Rhodnius genomes, which suggests a complex evolutionary interplay between vampire bugs and their intracellular symbiont. This nice piece of work thus provides valuable information to the fields of multiple partners / nutritional symbioses and Wolbachia research. Dual symbioses described in insects feeding on unbalanced diets generally highlight a certain complementarity between symbionts that ensure the whole nutritional complementation. The study presented by Filée et al. leads rather to consider the impact of multiple symbionts with different lifestyles and transmission modes in the provision of a specific nutritional benefit (here, biotin). Because of the low prevalence of Wolbachia in certain species, a “ménage à trois” scenario would rather be replaced by an “open couple”, where the host relationship with new symbiotic partners (more or less stable at the evolutionary timescale) could provide benefits in certain ecological situations. The results also support the potential for Wolbachia to evolve rapidly along a continuum between parasitism and mutualism, by acquiring operons encoding critical pathways of vitamin biosynthesis. References Duron O. and Gottlieb Y. (2020) Convergence of Nutritional Symbioses in Obligate Blood Feeders. Trends in Parasitology 36(10):816-825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.07.007 Filée J., Agésilas-Lequeux K., Lacquehay L., Bérenger J.-M., Dupont L., Mendonça V., Aristeu da Rosa J. and Harry M. (2023) Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs. bioRxiv, 2022.09.06.506778, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.06.506778 Gilliland C.A. et al. (2022) Using axenic and gnotobiotic insects to examine the role of different microbes on the development and reproduction of the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16800 Nikoh et al. (2014) Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. PNAS. 111(28):10257-10262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409284111 Pachebat, J.A. et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of Rhodococcus rhodnii strain LMG5362, a symbiont of Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae), the principle vector of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genome Announc. 1(3):e00329-13. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomea.00329-13 Salcedo-Porras N., et al. (2020). The role of bacterial symbionts in Triatomines: an evolutionary perspective. Microorganisms. 8:1438. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms8091438 Tobias N.J., Eberhard F.E., Guarneri A.A. (2020) Enzymatic biosynthesis of B-complex vitamins is supplied by diverse microbiota in the Rhodnius prolixus anterior midgut following Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 3395-3401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.031 | Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs | Jonathan Filée, Kenny Agésilas-Lequeux, Laurie Lacquehay, Jean Michel Bérenger, Lise Dupont, Vagner Mendonça, João Aristeu da Rosa, Myriam Harry | <p>The nutritional symbiosis promoted by bacteria is a key determinant for adaptation and evolution of many insect lineages. A complex form of nutritional mutualism that arose in blood-sucking insects critically depends on diverse bacterial symbio... |  | Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Species interactions | Natacha Kremer | Alejandro Manzano Marín | 2022-09-13 17:36:46 | View |

08 Aug 2018

Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutationsE. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David https://doi.org//273367Inbreeding compensates for reduced sexual selection in purging deleterious mutationsRecommended by Charles Baer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTwo evolutionary processes have been shown in theory to enhance the effects of natural selection in purging deleterious mutations from a population (here ""natural"" selection is defined as ""selection other than sexual selection""). First, inbreeding, especially self-fertilization, facilitates the removal of deleterious recessive alleles, the effects of which are largely hidden from selection in heterozygotes when mating is random. Second, sexual selection can facilitate the removal of deleterious alleles of arbitrary dominance, with little or no demographic cost, provided that deleterious effects are greater in males than in females (""genic capture""). Inbreeding (especially selfing) and sexual selection are often negatively correlated in nature. Empirical tests of the role of sexual selection in purging deleterious mutations have been inconsistent, potentially due to the positive relationship between sexual selection and intersexual genetic conflict. References [1] Noël, E., Fruitet, E., Lelaurin, D., Bonel, N., Segard, A., Sarda, V., Jarne, P., & David P. (2018). Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations. bioRxiv, 273367, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/273367 | Sexual selection and inbreeding: two efficient ways to limit the accumulation of deleterious mutations | E. Noël, E. Fruitet, D. Lelaurin, N. Bonel, A. Ségard, V. Sarda, P. Jarne and P. David | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100055). Theory and empirical data showed that two processes can boost selection against deleterious mutations, ... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Baer | Anonymous | 2018-03-01 08:12:37 | View |

12 Nov 2020

Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentThibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.23.217091Review and Assessment of Performance of Genomic Inference Methods based on the Sequentially Markovian CoalescentRecommended by Stephan Schiffels based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

The human genome not only encodes for biological functions and for what makes us human, it also encodes the population history of our ancestors. Changes in past population sizes, for example, affect the distribution of times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of genomic segments, which in turn can be inferred by sophisticated modelling along the genome. References [1] Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2011). Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature, 475(7357), 493-496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10231 | Limits and Convergence properties of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent | Thibaut Sellinger, Diala Abu Awad, Aurélien Tellier | <p>Many methods based on the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) have been and are being developed. These methods make use of genome sequence data to uncover population demographic history. More recently, new methods have extended the original... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics | Stephan Schiffels | Anonymous | 2020-07-25 10:54:48 | View |

25 Sep 2023

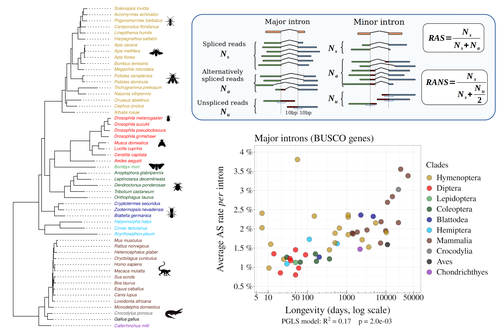

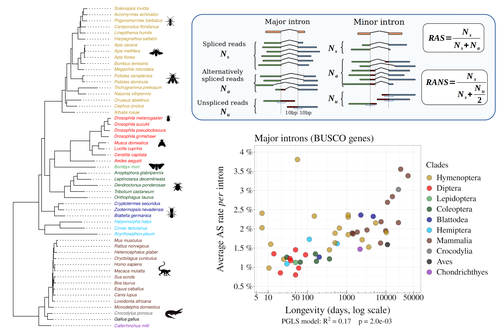

Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoansFlorian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597The drift barrier hypothesis and the limits to alternative splicing accuracyRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Lars M. Jakt and 2 anonymous reviewersAccurate information flow is central to living systems. The continuity of genomes through generations as well as the reproducible functioning and survival of the individual organisms require a faithful information transfer during replication, transcription and translation. The differential efficiency of natural selection against “mistakes” results in decreasing fidelity rates for replication, transcription and translation. At each level in the information flow chain (replication, transcription, translation), numerous complex molecular systems have evolved and been selected for preventing, identifying and, when possible, correcting or removing such “mistakes” arising during information transfer. However, fidelity cannot be improved ad infinitum. First, because of the limits imposed by the physical nature of the processes of copying and recoding information over different molecular supports: all mechanisms ensuring fidelity during biological information transfer ultimately rely on chemical kinetics and thermodynamics. The more accurate a copying process is, the lower the synthesis rate and the higher the energetic cost of correcting errors. Second, because of the limits imposed by random genetic drift: natural selection cannot effectively act on an allele that contributes with a small differential advantage unless effective population size is large. If s <1/Ne (or s <1/(2Ne) in diploids) the allele frequency in the population is de facto subject to neutral drift processes. In their preprint “Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans”, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret explore the validity of this last mentioned “drift barrier” hypothesis for the case study of alternative splicing diversity in eukaryotes (Bénitière et al. 2022). Splicing refers to an ensemble of eukaryotic molecular processes mediated by a large number of proteins and ribonucleoproteins and involving nucleotide sequence recognition, that uses as a molecular substrate a precursor messenger RNA (mRNA), directly transcribed from the DNA, and produces a mature mRNA by removing introns and joining exons (Chow et al. 1977). Alternative splicing refers to the case in which different molecular species of mature mRNAs can be produced, either by cis-splicing processes acting on the same precursor mRNA, e.g. by varying the presence/absence of different exons or by varying the exon-exon boundaries, or by trans-splicing processes, joining exons from different precursor mRNA molecules. The diversity of mRNA molecular species generated by alternative splicing enlarges the molecular phenotypic space that can be generated from the same genotype. In humans, alternative splicing occurs in around 95% of the ca. 20,000 genes, resulting in ca. 100,000 medium-to-high abundance transcripts (Pan et al. 2008). In multicellular organisms, the frequency of alternatively spliced mRNAs varies between tissues and across ontogeny, often in a switch-like pattern (Wang et al. 2008). In the molecular and cell biology community, it is commonly accepted that splice variants contribute with specific functions (Marasco and Kornblihtt 2023) although there exists a discussion around the functional nature of low-frequency splice variants (see for instance the debate between Tress et al. 2017 and Blencowe 2017). The origin, diversity, regulation and evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing constitutes thus a playground of the selectionist-neutralist debate, with one extreme considering that most splice variants are mere “mistakes” of the splicing process (Pickrell et al. 2010), and the other extreme considering that alternative splicing is at the core of complexity in multicellular organisms, as it increases the genome coding potential and allows for a large repertoire of cell types (Chen et al. 2014). In their manuscript, Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret set the cursor towards the neutralist end of the gradient and test the hypothesis of whether the high alternative splice rate in “complex” organisms corresponds to a high rate of splicing “mistakes”, arising from the limit imposed by the drift barrier effect on the power of natural selection to increase accuracy (Bush et al. 2017). In their preprint, the authors convincingly show that in metazoans a fraction of the variation of alternative splicing rate is explained by variation in proxies of population size, so that species with smaller Ne display higher alternative splice rates. They communicate further that abundant splice variants tend to preserve the reading frame more often than low-frequency splice variants, and that the nucleotide splice signals in abundant splice variants display stronger evidence of purifying selection than those in low-frequency splice variants. From all the evidence presented in the manuscript, the authors interpret that “variation in alternative splicing rate is entirely driven by variation in the efficacy of selection against splicing errors”. The authors honestly present some of the limitations of the data used for the analyses, regarding i) the quality of the proxies used for Ne (i.e. body length, longevity and dN/dS ratio); ii) the heterogeneous nature of the RNA sequencing datasets (full organisms, organs or tissues; different life stages, sexes or conditions); and iii) mostly short RNA reads that do not fully span individual introns. Further, data from bacteria do not verify the herein communicated trends, as it has been shown that bacterial species with low population sizes do not display higher transcription error rates (Traverse and Ochman 2016). Finally, it will be extremely interesting to introduce a larger evolutionary perspective on alternative splicing rates encompassing unicellular eukaryotes, in which an intriguing interplay between alternative splicing and gene duplication has been communicated (Hurtig et al. 2020). The manuscript from Bénitière, Necsulea and Duret makes a significant advance to our understanding of the diversity, the origin and the physiology of post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms by emphasising the fundamental role of non-adaptive evolutionary processes and the upper limits to splicing accuracy set by genetic drift. References Bénitière F, Necsulea A, Duret L. 2023. Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.09.519597 Blencowe BJ. 2017. The Relationship between Alternative Splicing and Proteomic Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:407–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.001 Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, Urrutia AO. 2017. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20150474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 Chen L, Bush SJ, Tovar-Corona JM, Castillo-Morales A, Urrutia AO. 2014. Correcting for differential transcript coverage reveals a strong relationship between alternative splicing and organism complexity. Mol Biol Evol 31:1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu083 Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ. 1977. An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5’ ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell 12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5 Hurtig JE, Kim M, Orlando-Coronel LJ, Ewan J, Foreman M, Notice L-A, Steiger MA, van Hoof A. 2020. Origin, conservation, and loss of alternative splicing events that diversify the proteome in Saccharomycotina budding yeasts. RNA 26:1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.075655.120 Marasco LE, Kornblihtt AR. 2023. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. 2008. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 40:1413–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.259 Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. 2010. Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells. PLoS Genet 6:e1001236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236 Traverse CC, Ochman H. 2016. Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3311–3316. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525329113 Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. 2017. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci 42:98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008 Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07509 | Random genetic drift sets an upper limit on mRNA splicing accuracy in metazoans | Florian Benitiere, Anamaria Necsulea, Laurent Duret | <p style="text-align: justify;">Most eukaryotic genes undergo alternative splicing (AS), but the overall functional significance of this process remains a controversial issue. It has been noticed that the complexity of organisms (assayed by the nu... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Ignacio Bravo | Anonymous | 2022-12-12 14:00:01 | View |

10 Jan 2019

Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruceJun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux https://doi.org/10.1101/402016Disentangling the recent and ancient demographic history of European spruce speciesRecommended by Jason Holliday based on reviews by 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic diversity in temperate and boreal forests tree species has been strongly affected by late Pleistocene climate oscillations [2,3,5], but also by anthropogenic forces. Particularly in Europe, where a long history of human intervention has re-distributed species and populations, it can be difficult to know if a given forest arose through natural regeneration and gene flow or through some combination of natural and human-mediated processes. This uncertainty can confound inferences of the causes and consequences of standing genetic variation, which may impact our interpretation of demographic events that shaped species before humans became dominant on the landscape. In their paper entitled "Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce", Chen et al. [1] used a genome-wide dataset of 400k SNPs to infer the demographic history of Picea abies (Norway spruce), the most widespread and abundant spruce species in Europe, and to understand its evolutionary relationship with two other spruces (Picea obovata [Siberian spruce] and P. omorika [Serbian spruce]). Three major Norway spruce clusters were identified, corresponding to central Europe, Russia and the Baltics, and Scandinavia, which agrees with previous studies. The density of the SNP data in the present paper enabled inference of previously uncharacterized admixture between these groups, which corresponds to the timing of postglacial recolonization following the last glacial maximum (LGM). This suggests that multiple migration routes gave rise to the extant distribution of the species, and may explain why Chen et al.'s estimates of divergence times among these major Norway spruce groups were older (15mya) than those of previous studies (5-6mya) – those previous studies may have unknowingly included admixed material [4]. Treemix analysis also revealed extensive admixture between Norway and Siberian spruce over the last ~100k years, while the geographically-restricted Serbian spruce was both isolated from introgression and had a dramatically smaller effective population size (Ne) than either of the other two species. This small Ne resulted from a bottleneck associated with the onset of the iron age ~3000 years ago, which suggests that anthropogenic depletion of forest resources has severely impacted this species. Finally, ancestry of Norway spruce samples collected in Sweden and Denmark suggest their recent transfer from more southern areas of the species range. This northward movement of genotypes likely occurred because the trees performed well relative to local provenances, which is a common observation when trees from the south are planted in more northern locations (although at the potential cost of frost damage due to inappropriate phenology). While not the reason for the transfer, the incorporation of southern seed sources into the Swedish breeding and reforestation program may lead to more resilient forests under climate change. Taken together, the data and analysis presented in this paper allowed inference of the intra- and interspecific demographic histories of a tree species group at a very high resolution, and suggest caveats regarding sampling and interpretation of data from areas with a long history of occupancy by humans. References [1] Chen, J., Milesi, P., Jansson, G., Berlin, M., Karlsson, B., Aleksić, J. M., Vendramin, G. G., Lascoux, M. (2018). Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce. BioRxiv, 402016. ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/402016 | Genomic data provides new insights on the demographic history and the extent of recent material transfers in Norway spruce | Jun Chen, Lili Li, Pascal Milesi, Gunnar Jansson, Mats Berlin, Bo Karlsson, Jelena Aleksic, Giovanni G Vendramin, Martin Lascoux | <p>Primeval forests are today exceedingly rare in Europe and transfer of forest reproductive material for afforestation and improvement have been very common, especially over the last two centuries. This can be a serious impediment when inferring ... | Evolutionary Applications, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Jason Holliday | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2018-08-29 08:33:15 | View | |

02 Feb 2023

Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibilityKatherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663Susceptibility to infection is not explained by sex or differences in tissue tropism across different species of DrosophilaRecommended by Alison Duncan based on reviews by Greg Hurst and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding factors explaining both intra and interspecific variation in susceptibility to infection by parasites remains a key question in evolutionary biology. Within a species variation in susceptibility is often explained by differences in behaviour affecting exposure to infection and/or resistance affecting the degree by which parasite growth is controlled (Roy & Kirchner, 2000, Behringer et al., 2000). This can vary between the sexes (Kelly et al., 2018) and may be explained by the ability of a parasite to attack different organs or tissues (Brierley et al., 2019). However, what goes on within one species is not always relevant to another, making it unclear when patterns can be scaled up and generalised across species. This is also important to understand when parasites may jump hosts, or identify species that may be susceptible to a host jump (Longdon et al., 2015). Phylogenetic distance between hosts is often an important factor explaining susceptibility to a particular parasite in plant and animal hosts (Gilbert & Webb, 2007, Faria et al., 2013). In two separate experiments, Roberts and Longdon (Roberts & Longdon, 2022) investigated how sex and tissue tropism affected variation in the load of Drosophila C Virus (DCV) across multiple Drosophila species. DCV load has been shown to correlate positively with mortality (Longdon et al., 2015). Overall, they found that load did not vary between the sexes; within a species males and females had similar DCV loads for 31 different species. There was some variation in levels of DCV growth in different tissue types, but these too were consistent across males for 7 species of Drosophila. Instead, in both experiments, host phylogeny or interspecific variation, explained differences in DCV load with some species being more infected than others. This study is neat in that it incorporates and explores simultaneously both intra and interspecific variation in infection-related life-history traits which is not often done (but see (Longdon et al., 2015, Imrie et al., 2021, Longdon et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2012). Indeed, most studies to date explore either inter-specific differences in susceptibility to a parasite (it can or can’t infect a given species) (Davies & Pedersen, 2008, Pfenning-Butterworth et al., 2021) or intra-specific variability in infection-related traits (infectivity, resistance etc.) due to factors such as sex, genotype and environment (Vale et al., 2008, Lambrechts et al., 2006). This work thus advances on previous studies, while at the same time showing that sex differences in parasite load are not necessarily pervasive. References Behringer DC, Butler MJ, Shields JD (2006) Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature, 441, 421–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/441421a Brierley L, Pedersen AB, Woolhouse MEJ (2019) Tissue tropism and transmission ecology predict virulence of human RNA viruses. PLOS Biology, 17, e3000206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000206 Davies TJ, Pedersen AB (2008) Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.0284 Faria NR, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Streicker DG, Lemey P (2013) Simultaneously reconstructing viral cross-species transmission history and identifying the underlying constraints. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368, 20120196. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0196 Gilbert GS, Webb CO (2007) Phylogenetic signal in plant pathogen–host range. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 4979–4983. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607968104 Imrie RM, Roberts KE, Longdon B (2021) Between virus correlations in the outcome of infection across host species: Evidence of virus by host species interactions. Evolution Letters, 5, 472–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.247 Johnson PTJ, Rohr JR, Hoverman JT, Kellermanns E, Bowerman J, Lunde KB (2012) Living fast and dying of infection: host life history drives interspecific variation in infection and disease risk. Ecology Letters, 15, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01730.x Kelly CD, Stoehr AM, Nunn C, Smyth KN, Prokop ZM (2018) Sexual dimorphism in immunity across animals: a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters, 21, 1885–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13164 Lambrechts L, Chavatte J-M, Snounou G, Koella JC (2006) Environmental influence on the genetic basis of mosquito resistance to malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 1501–1506. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3483 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Day JP, Smith SCL, McGonigle JE, Cogni R, Cao C, Jiggins FM (2015) The Causes and Consequences of Changes in Virulence following Pathogen Host Shifts. PLOS Pathogens, 11, e1004728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004728 Longdon B, Hadfield JD, Webster CL, Obbard DJ, Jiggins FM (2011) Host Phylogeny Determines Viral Persistence and Replication in Novel Hosts. PLOS Pathogens, 7, e1002260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002260 Pfenning-Butterworth AC, Davies TJ, Cressler CE (2021) Identifying co-phylogenetic hotspots for zoonotic disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376, 20200363. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0363 Roberts KE, Longdon B (2023) Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: examining sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility. bioRxiv 2022.11.01.514663, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514663 Roy BA, Kirchner JW (2000) Evolutionary Dynamics of Pathogen Resistance and Tolerance. Evolution, 54, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00007.x Vale PF, Stjernman M, Little TJ (2008) Temperature-dependent costs of parasitism and maintenance of polymorphism under genotype-by-environment interactions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01555.x | Heterogeneities in infection outcomes across species: sex and tissue differences in virus susceptibility | Katherine E Roberts, Ben Longdon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Species vary in their susceptibility to pathogens, and this can alter the ability of a pathogen to infect a novel host. However, many factors can generate heterogeneity in infection outcomes, obscuring our ability t... | Evolutionary Ecology | Alison Duncan | Anonymous, Greg Hurst | 2022-11-03 11:17:42 | View | |

31 Mar 2022

Gene network robustness as a multivariate characterArnaud Le Rouzic https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564Genetic and environmental robustness are distinct yet correlated evolvable traits in a gene networkRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert

Organisms often show robustness to genetic or environmental perturbations. Whether these two components of robustness can evolve separately is the focus of the paper by Le Rouzic [1]. Using theoretical analysis and individual-based computer simulations of a gene regulatory network model, he shows that multiple aspects of robustness can be investigated as a set of pleiotropically linked quantitative traits. While genetically correlated, various robustness components (e.g., mutational, developmental, homeostasis) of gene expression in the regulatory network evolved more or less independently from each other under directional selection. The quantitative approach of Le Rouzic could explain both how unselected robustness components can respond to selection on other components and why various robustness-related features seem to have their own evolutionary history. Moreover, he shows that all components were evolvable, but not all to the same extent. Robustness to environmental disturbances and gene expression stability showed the largest responses while increased robustness to genetic disturbances was slower. Interestingly, all components were positively correlated and remained so after selection for increased or decreased robustness. This study is an important contribution to the discussion of the evolution of robustness in biological systems. While it has long been recognized that organisms possess the ability to buffer genetic and environmental perturbations to maintain homeostasis (e.g., canalization [2]), the genetic basis and evolutionary routes to robustness and canalization are still not well understood. Models of regulatory gene networks have often been used to address aspects of robustness evolution (e.g., [3]). Le Rouzic [1] used a gene regulatory network model derived from Wagner’s model [4]. The model has as end product the expression level of a set of genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors). The level and stability of expression are a property of the regulatory interactions in the network. Le Rouzic made an important contribution to the study of such gene regulation models by using a quantitative genetics approach to the evolution of robustness. He crafted a way to assess the mutational variability and selection response of the components of robustness he was interested in. Le Rouzic’s approach opens avenues to investigate further aspects of gene network evolutionary properties, for instance to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Le Rouzic also discusses ways to measure his different robustness components in empirical studies. As the model is about gene expression levels at a set of protein-coding genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements, it naturally points to the possibility of using RNA sequencing to measure the variation of gene expression in know gene networks and assess their robustness. Robustness could then be studied as a multidimensional quantitative trait in an experimental setting. References [1] Le Rouzic, A (2022) Gene network robustness as a multivariate character. arXiv: 2101.01564, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564 [2] Waddington CH (1942) Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/150563a0 [3] Draghi J, Whitlock M (2015) Robustness to noise in gene expression evolves despite epistatic constraints in a model of gene networks. Evolution, 69, 2345–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12732 [4] Wagner A (1994) Evolution of gene networks by gene duplications: a mathematical model and its implications on genome organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 4387–4391. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.10.4387 | Gene network robustness as a multivariate character | Arnaud Le Rouzic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Robustness to genetic or environmental disturbances is often considered as a key property of living systems. Yet, in spite of being discussed since the 1950s, how robustness emerges from the complexity of genetic ar... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | Charles Mullon, Charles Rocabert, Diogo Melo | 2021-01-11 17:48:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer