Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Aug 2022

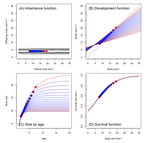

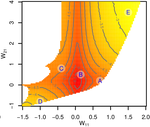

Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body sizeTim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952A population biological modeling approach for life history and body size evolutionRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 2 anonymous reviewersBody size evolution is a central theme in evolutionary biology. Particularly the question of when and how smaller body sizes can evolve continues to interest evolutionary ecologists, because most life history models, and the empirical evidence, document that large body size is favoured by natural and sexual selection in most (even small) organisms and environments at most times. How, then, can such a large range of body size and life history syndromes evolve and coexist in nature? The paper by Coulson et al. lifts this question to the level of the population, a relatively novel approach using so-called integral projection (simulation) models (IPMs) (as opposed to individual-based or game theoretical models). As is well outlined by (anonymous) Reviewer 1, and following earlier papers spearheading this approach in other life history contexts, the authors use the well-known carrying capacity (K) of population biology as the ultimate fitness parameter to be maximized or optimized (rather than body size per se), to ultimately identify factors and conditions promoting the evolution of extreme body sizes in nature. They vary (individual or population) size-structured growth trajectories to observe age and size at maturity, surivorship and fecundity/fertility schedules upon evaluating K (see their Fig. 1). Importantly, trade-offs are introduced via density-dependence, either for adult reproduction or for juvenile survival, in two (of several conceivable) basic scenarios (see their Table 2). All other relevant standard life history variables (see their Table 1) are assumed density-independent, held constant or zero (as e.g. the heritability of body size). The authors obtain evidence for disruptive selection on body size in both scenarios, with small size and a fast life history evolving below a threshold size at maturity (at the lowest K) and large size and a slow life history beyond this threshold (see their Fig. 2). Which strategy wins ultimately depends on the fitness benefits of delaying sexual maturity (at larger size and longer lifespan) at the adult stage relative to the preceeding juvenile mortality costs, in agreement with classic life history theory (Roff 1992, Stearns 1992). The modeling approach can be altered and refined to be applied to other key life history parameters and environments. These results can ultimately explain the evolution of smaller body sizes from large body sizes, or vice versa, and their corresponding life history syndromes, depending on the precise environmental circumstances. All reviewers agreed that the approach taken is technically sound (as far as it could be evaluated), and that the results are interesting and worthy of publication. In a first round of reviews various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers. The new version was substantially changed by the authors in response, to the extent that it now is a quite different but much clearer paper with a clear message palatable for the general reader. The writing is now to the point, the paper's focus becomes clear in the Introduction, Methods & Results are much less technical, the Figures illustrative, and the descriptions and interpretations in the Discussion are easy to follow. In general any reader may of course question the choice and realism of the scenarios and underlying assumptions chosen by the authors for simplicity and clarity, for instance no heritability of body size and no cost of reproduction (other than mortality). But this is always the case in modeling work, and the authors acknowledge and in fact suggest concrete extensions and expansions of their approach in the Discussion. References Coulson T., Felmy A., Potter T., Passoni G., Montgomery R.A., Gaillard J.-M., Hudson P.J., Travis J., Bassar R.D., Tuljapurkar S., Marshall D.J., Clegg S.M. (2022) Density-dependent environments can select for extremes of body size. bioRxiv, 2022.02.17.480952, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952 | Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body size | Tim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg | <p>Body size variation is an enigma. We do not understand why species achieve the sizes they do, and this means we also do not understand the circumstances under which gigantism or dwarfism is selected. We develop size-structured integral projecti... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2022-02-21 07:59:04 | View | |

10 Jul 2019

Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pestGeorgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin https://doi.org/10.1101/362129The scandalous pestRecommended by Nicolas Galtier based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersKoutsovoulos et al. [1] have generated and analysed the first population genomic dataset in root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Why is this interesting? For two major reasons. First, M. incognita has been documented to be apomictic, i.e., to lack any form of sex. This is a trait of major evolutionary importance, with implications on species adaptive potential. The study of genome evolution in asexuals is fascinating and has the potential to inform on the forces governing the evolution of sex and recombination. Even small amounts of sex, however, are sufficient to restore most of the population genetic properties of true sexuals [2]. Because rare events of sex can remain undetected in the field, to confirm asexuality in M. incognita using genomic data is an important step. The second reason why M. incognita is of interest is that this nematode is one of the most harmful pests currently living on earth. M. incognita feeds on the roots of many cultivated plants, including tomato, bean, and cotton, and has been of major agricultural importance for decades. A number of races were defined based on host specificity. These have played a key role in attempts to control the dynamic of M. incognita populations via crop rotations. Races and management strategies so far lack any genetic basis, hence the second major interest of this study. References [1] Koutsovoulos, G. D., Marques, E., Arguel, M. J., Duret, L., Machado, A. C. Z., Carneiro, R. M. D. G., Kozlowski, D. K., Bailly-Bechet, M., Castagnone-Sereno, P., Albuquerque, E. V., & Danchin, E. G. J. (2019). Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest. bioRxiv, 362129, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/362129 | Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode plant pest | Georgios D. Koutsovoulos, Eder Marques, Marie-Jeanne Arguel, Laurent Duret, Andressa C.Z. Machado, Regina M.D.G. Carneiro, Djampa K. Kozlowski, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Erika V.S. Albuquerque, Etienne G.J. Danchin | <p>The most devastating nematodes to worldwide agriculture are the root-knot nematodes with Meloidogyne incognita being the most widely distributed and damaging species. This parasitic and ecological success seem surprising given its supposed obli... | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Galtier | 2018-08-24 09:02:33 | View | ||

26 Aug 2021

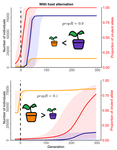

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal ratesSolenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4How to estimate clonality from genetic data: use large samples and consider the biology of the speciesRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by David Macaya-Sanz, Marcela Van Loo and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population geneticists frequently use the genetic and genotypic information of a population sample of individuals to make inferences on the reproductive system of a species. The detection of clones, i.e. individuals with the same genotype, can give information on whether there is clonal (vegetative) reproduction in the species. If clonality is detected, population geneticists typically use genotypic richness R, the number of distinct genotypes relative to the sample size, to estimate the rate of clonality c, which can be defined as the proportion of reproductive events that are clonal. Estimating the rate of clonality based on genotypic richness is however problematic because, to date, there is no analytical, nor simulation-based, characterization of this relationship. Furthermore, the effect of sampling on this relationship has never been critically examined. References [1] Stoeckel, S., Porro, B., and Arnaud-Haond, S. (2019). The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates. ArXiv:1902.09365 [q-Bio] v4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09365v4 | The discernible and hidden effects of clonality on the genotypic and genetic states of populations: improving our estimation of clonal rates | Solenn Stoeckel, Barbara Porro, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Partial clonality is widespread across the tree of life, but most population genetics models are conceived for exclusively clonal or sexual organisms. This gap hampers our understanding of the influence of clonality on evolutionary trajectories... |  | Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Myriam Heuertz | 2019-02-28 10:10:56 | View | |

29 Sep 2022

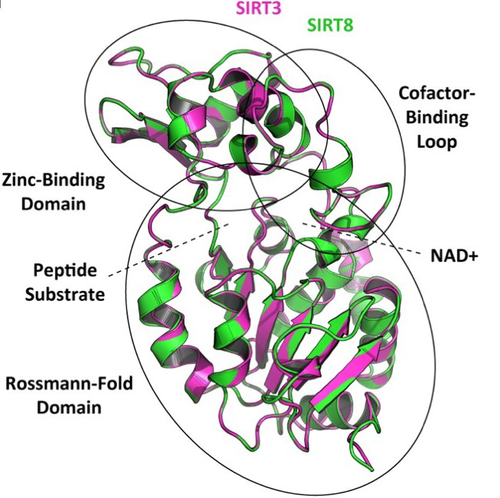

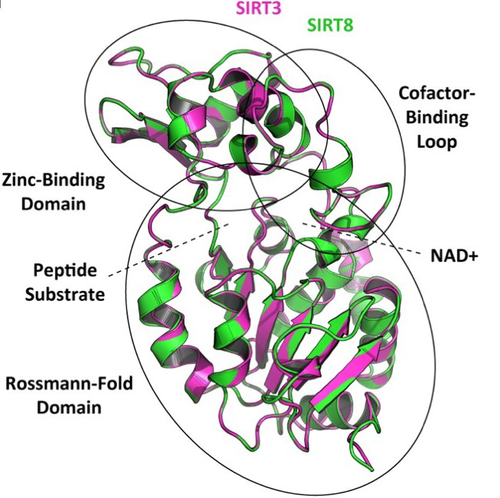

How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family memberJuan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510Making sense of vertebrate sirtuin genesRecommended by Frédéric Delsuc based on reviews by Filipe Castro, Nicolas Leurs and 1 anonymous reviewerSirtuin proteins are class III histone deacetylases that are involved in a variety of fundamental biological functions mostly related to aging. These proteins are located in different subcellular compartments and are associated with different biological functions such as metabolic regulation, stress response, and cell cycle control [1]. In mammals, the sirtuin gene family is composed of seven paralogs (SIRT1-7) grouped into four classes [2]. Due to their involvement in maintaining cell cycle integrity, sirtuins have been studied as a way to understand fundamental mechanisms governing longevity [1]. Indeed, the downregulation of sirtuin genes with aging seems to explain much of the pathophysiology that accumulates with aging [3]. Biomedical studies have thus explored the potential therapeutic implications of sirtuins [4] but whether they can effectively be used as molecular targets for the treatment of human diseases remains to be demonstrated [1]. Despite this biomedical interest and some phylogenetic analyses of sirtuin paralogs mostly conducted in mammals, a comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the sirtuin gene family at the scale of vertebrates was still lacking. In this preprint, Opazo and collaborators [5] took advantage of the increasing availability of whole-genome sequences for species representing all main groups of vertebrates to unravel the evolution of the sirtuin gene family. To do so, they undertook a phylogenomic approach in its original sense aimed at improving functional predictions by evolutionary analysis [6] in order to inventory the full vertebrate sirtuin gene repertoire and reconstruct its precise duplication history. Harvesting genomic databases, they extracted all predicted sirtuin proteins and performed phylogenetic analyses based on probabilistic inference methods. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses resulted in well-resolved and congruent phylogenetic trees dividing vertebrate sirtuin genes into three major clades. These analyses also revealed an additional eighth paralog that was previously overlooked because of its restricted phyletic distribution. This newly identified sirtuin family member (named SIRT8) was recovered with unambiguous statistical support as a sister-group to the SIRT3 clade. Comparative genomic analyses based on conserved gene synteny confirmed that SIRT8 was present in all sampled non-amniote vertebrate genomes (cartilaginous fish, bony fish, coelacanth, lungfish, and amphibians) except cyclostomes. SIRT8 has thus most likely been lost in the last common ancestor of amniotes (mammals, reptiles, and birds). Discovery of such previously unknown genes in vertebrates is not completely surprising given the plethora of high-quality genomes now available. However, this study highlights the importance of considering a broad taxonomic sampling to infer evolutionary patterns of gene families that have been mostly studied in mammals because of their potential importance for human biology. Based on its phylogenetic position as closely related to SIRT3 within class I, it could be predicted that the newly identified SIRT8 paralog likely has a deacetylase activity and is probably located in mitochondria. To test these evolutionary predictions, Opazo and collaborators [5] conducted further bioinformatics analyses and functional experiments using the elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii) as a model species. RNAseq expression data were analyzed to determine tissue-specific transcription of sirtuin genes in vertebrates, including SIRT8 found to be mainly expressed in the ovary, which suggests a potential role in biological processes associated with reproduction. The elephant shark SIRT8 protein sequence was used with other vertebrates for comparative analyses of protein structure modeling and subcellular localization prediction both pointing to a probable mitochondrial localization. The protein localization and its function were further characterized by immunolocalization in transfected cells, and enzymatic and functional assays, which all confirmed the prediction that SIRT8 proteins are targeted to the mitochondria and have deacetylase activity. The extensive experimental efforts made in this study to shed light on the function of this newly discovered gene are both rare and highly commendable. Overall, this work by Opazo and collaborators [5] provides a comprehensive phylogenomic study of the sirtuin gene family in vertebrates based on detailed evolutionary analyses using state-of-the-art phylogenetic reconstruction methods. It also illustrates the power of adopting an integrative comparative approach supplementing the reconstruction of the duplication history of the gene family with complementary functional experiments in order to elucidate the function of the newly discovered SIRT8 family member. These results provide a reference phylogenetic framework for the evolution of sirtuin genes and the further functional characterization of the eight vertebrate paralogs with potential relevance for understanding the cellular biology of aging and its associated diseases in human. References [1] Vassilopoulos A, Fritz KS, Petersen DR, Gius D (2011) The human sirtuin family: Evolutionary divergences and functions. Human Genomics, 5, 485. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-5-5-485 [2] Yamamoto H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J (2007) Sirtuin Functions in Health and Disease. Molecular Endocrinology, 21, 1745–1755. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2007-0079 [3] Morris BJ (2013) Seven sirtuins for seven deadly diseases ofaging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 56, 133–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.525 [4] Bordo D Structure and Evolution of Human Sirtuins. Current Drug Targets, 14, 662–665. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1389450111314060007 [5] Opazo JC, Vandewege MW, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Meléndez C, Luchsinger C, Cavieres VA, Vargas-Chacoff L, Morera FJ, Burgos PV, Tapia-Rojas C, Mardones GA (2022) How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member. bioRxiv, 2020.07.17.209510, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.17.209510 [6] Eisen JA (1998) Phylogenomics: Improving Functional Predictions for Uncharacterized Genes by Evolutionary Analysis. Genome Research, 8, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.8.3.163 | How many sirtuin genes are out there? evolution of sirtuin genes in vertebrates with a description of a new family member | Juan C. Opazo, Michael W. Vandewege, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Catalina Meléndez, Charlotte Luchsinger, Viviana A. Cavieres, Luis Vargas-Chacoff, Francisco J. Morera, Patricia V. Burgos, Cheril Tapia-Rojas, Gonzalo A. Mardones | <p style="text-align: justify;">Studying the evolutionary history of gene families is a challenging and exciting task with a wide range of implications. In addition to exploring fundamental questions about the origin and evolution of genes, disent... |  | Molecular Evolution | Frédéric Delsuc | Filipe Castro, Anonymous, Nicolas Leurs | 2022-05-12 16:06:04 | View |

09 Dec 2019

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snailsPilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pereira, Luiggi Martini Robles, Richar Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Nelson Uribe, Patrice David, Philippe Jarne, Jean-Pierre Pointier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès https://doi.org/10.1101/647867The challenge of delineating species when they are hiddenRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms. References [1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press. | Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails | Pilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pere... | <p>Cryptic species can present a significant challenge to the application of systematic and biogeographic principles, especially if they are invasive or transmit parasites or pathogens. Detecting cryptic species requires a pluralistic approach in ... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Systematics / Taxonomy | Fabien Condamine | Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse | 2019-05-25 10:34:57 | View |

28 Sep 2020

Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantageLudovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens https://doi.org/10.1101/616409Evolutionary insights into disassortative mating and its association to an ecologically relevant supergeneRecommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers

Heliconius butterflies are famous for their colorful wing patterns acting as a warning of their chemical defenses [1]. Most species are involved in Müllerian mimicry assemblies, as predators learn to associate common wing patterns with unpalatability and preferentially target rare variants. Such positive-frequency dependent selection homogenizes wing patterns at different localities, and in several species, all individuals within a community belong to the same morph [2]. In this respect, H. numata stands out. This species shows stable local polymorphism across multiple localities, with local populations home to up to seven distinct morphs [2]. Although a balance between migration and local positive-frequency dependent selection can allow some degree of local polymorphism, theory suggests that this occurs only when migration is within a narrow window [3]. References [1] Merrill, R M, K K Dasmahapatra, J W Davey, D D Dell'Aglio, J J Hanly, B Huber, C D Jiggins, et al. (2015). The Diversification of Heliconius butterflies: What Have We Learned in 150 Years? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28 (8), 1417–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12672. | Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantage | Ludovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens | <p>The evolution of mate preferences may depend on natural selection acting on the mating cues and on the underlying genetic architecture. While the evolution of assortative mating with respect to locally adapted traits has been well-characterized... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Mullon | 2019-10-29 09:55:18 | View | |

11 May 2023

Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineagesAlejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559Flexibility in Aphid Endosymbiosis: Dual Symbioses Have Evolved Anew at Least Six TimesRecommended by Olivier Tenaillon based on reviews by Alex C. C. Wilson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this intriguing study (Manzano-Marín et al. 2022) by Alejandro Manzano-Marin and his colleagues, the association between aphids and their symbionts is investigated through meta-genomic analysis of new samples. These associations have been previously described as leading to fascinating genomic evolution in the symbiont (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). The bacterial genomes exhibit a significant reduction in size and the range of functions performed. They typically lose the ability to produce many metabolites or biobricks created by the host, and instead, streamline their metabolism by focusing on the amino acids that the host cannot produce. This level of co-evolution suggests a stable association between the two partners. However, the new data suggests a much more complex pattern as multiple independent acquisitions of co-symbionts are observed. Co-symbiont acquisition leads to a partition of the functions carried out on the bacterial side, with the new co-symbiont taking over some of the functions previously performed by Buchnera. In most cases, the new co-symbiont also brings the ability to produce B1 vitamin. Various facultative symbiotic taxa are recruited to be co-symbionts, with the frequency of acquisition related to the bacterial niche and lifestyle. REFERENCES Manzano-Marín, Alejandro, Armelle Coeur D’acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, and Emmanuelle Jousselin. 2023. “Co-Obligate Symbioses Have Repeatedly Evolved across Aphids, but Partner Identity and Nutritional Contributions Vary across Lineages.” bioRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.28.505559. McCutcheon, John P., and Nancy A. Moran. 2012. “Extreme Genome Reduction in Symbiotic Bacteria.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670. | Co-obligate symbioses have repeatedly evolved across aphids, but partner identity and nutritional contributions vary across lineages | Alejandro Manzano-Marín, Armelle Coeur d'acier, Anne-Laure Clamens, Corinne Cruaud, Valérie Barbe, Emmanuelle Jousselin | <p style="text-align: justify;">Aphids are a large family of phloem-sap feeders. They typically rely on a single bacterial endosymbiont, <em>Buchnera aphidicola</em>, to supply them with essential nutrients lacking in their diet. This association ... |  | Genome Evolution, Other, Species interactions | Olivier Tenaillon | 2022-11-16 10:13:37 | View | |

13 Nov 2023

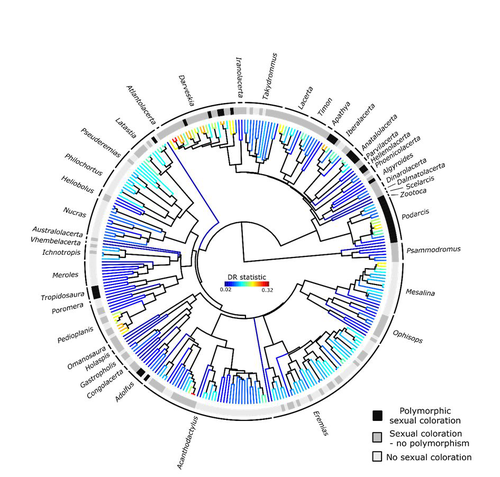

Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in LacertidsThomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678Colour polymorphism does not increase diversification rates in lizardsRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe striking differences in species richness among lineages in the Tree of Life have long attracted much research interest. In particular, researchers have asked whether certain traits are associated with greater diversification, with a particular focus on traits under sexual selection given their direct link to mating isolation. Polymorphism, defined as the presence of co-occurring, heritable morphs within a population, has been proposed to influence diversification rates although the effect has been proposed as both promoting or alternatively impeding speciation. The effect of polymorphism may be positive, that is facilitating speciation if polymorphism allows to broaden the ecological niche, thus enabling range expansion, or enabling maintenance of populations in variable environments. Specialized ectomorphs have been observed in several species (e.g. Kusche et al. 2015, Lattanzio and Miles 2016, Whitney et al. 2018, Scali et al. 2016). Polymorphism may also facilitate speciation if a morph is lost during the colonization of a novel area or niche, resulting in rapid divergence of the remaining morphs and reproductive isolation from the ancestral population, known as the morph speciation hypothesis (West-Eberhard 1986, Corl et al. 2010). On the other hand, polymorphism may hamper speciation through disassortative maintaining by morph, which may maintain the polymorphism through the speciation process (Jamie and Meier 2020). An example of such a process is Heliconius numata where disassortative mate preferences based on color hampers ecological speciation (Chouteau et al. 2017). Previous evidence in birds and lizards suggests polymorphism favors diversification (Corl et al. 2010b, 2012, Hugall and Stuart-Fox 2012, Brock et al. 2021). Here, de Solan et al. (2023) test the effect of polymorphism on diversification in Lacertidae, a family of lizards containing more than 300 species distributed across Europe, Africa and Asia. The group offers a good model system to test the effect of polymorphism on speciation as it contains several species with colour polymorphism, sometimes present in both sexes but restricted to males when present in the flank. Using coloration data from the literature as well as photographs of live specimens for 295 species the authors tested whether the presence of polymorphism is associated with higher diversification rates. While undertaking their project, another group independently tackled the same question (Brock et al. 2021), using the same model system but coming to very different conclusions. Therefore, de Solan et al. (2023) decided to also contrast their results with those of Brock et al. (2021) to determine the factors responsible for the contrasting results of both studies. The latter I consider one of the strengths of the work, given the careful re-analyses to determine the causes of the discrepancies between both studies. De Solan et al. (2023) found no association between the presence of polymorphism and diversification rates, even though they used different analytical approaches. Thus, this study is interesting as it provides results that do not support a positive effect of polymorphism on species richness. The use of a phylogeny with more limited species sampling (García-Porta et al. 2019) implied that the authors had to manually add 75 species, of which 17 were added to the tree based on information from previously published trees and 68 were added at random locations within the genus. To control for potential biases the authors repeated the analyses using a sample of trees with the imputed taxa, results were broadly concordant across the set of trees. The careful re-analysis contrasting Brock et al. (2021) and de Solan et al. (2023) results suggests the difference is mainly due to a difference in how species were coded as presenting polymorphism, which differed between the two studies, as well as a difference in the package version used to run the state-dependent diversification models. Interestingly non-parametric analyses yielded similar results across both datasets. Garcia-Porta, J., Irisarri, I., Kirchner, M. et al. 2019. Environmental temperatures shape thermal physiology as well as diversification and genome-wide substitution rates in lizards. Nature Communications. 10: 4077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11943-x de Solan T, Sinervo B, Geniez P, David P, Crochet P-A (2023) Colour polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids. bioRxiv, 2023.02.15.528678, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.15.528678 West-Eberhard, M.J. 1986. Alternative adaptations, speciation, and phylogeny (A review). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 83: 1388-1392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.5.1388 | Color polymorphism and conspicuousness do not increase speciation rates in Lacertids | Thomas de Solan, Barry Sinervo, Philippe Geniez, Patrice David, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Conspicuous body colors and color polymorphism have been hypothesized to increase rates of speciation. Conspicuous colors are evolutionary labile, and often involved in intraspecific sexual signaling and thus may pr... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Speciation | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2023-02-22 10:05:03 | View | |

31 Mar 2022

Gene network robustness as a multivariate characterArnaud Le Rouzic https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564Genetic and environmental robustness are distinct yet correlated evolvable traits in a gene networkRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert

Organisms often show robustness to genetic or environmental perturbations. Whether these two components of robustness can evolve separately is the focus of the paper by Le Rouzic [1]. Using theoretical analysis and individual-based computer simulations of a gene regulatory network model, he shows that multiple aspects of robustness can be investigated as a set of pleiotropically linked quantitative traits. While genetically correlated, various robustness components (e.g., mutational, developmental, homeostasis) of gene expression in the regulatory network evolved more or less independently from each other under directional selection. The quantitative approach of Le Rouzic could explain both how unselected robustness components can respond to selection on other components and why various robustness-related features seem to have their own evolutionary history. Moreover, he shows that all components were evolvable, but not all to the same extent. Robustness to environmental disturbances and gene expression stability showed the largest responses while increased robustness to genetic disturbances was slower. Interestingly, all components were positively correlated and remained so after selection for increased or decreased robustness. This study is an important contribution to the discussion of the evolution of robustness in biological systems. While it has long been recognized that organisms possess the ability to buffer genetic and environmental perturbations to maintain homeostasis (e.g., canalization [2]), the genetic basis and evolutionary routes to robustness and canalization are still not well understood. Models of regulatory gene networks have often been used to address aspects of robustness evolution (e.g., [3]). Le Rouzic [1] used a gene regulatory network model derived from Wagner’s model [4]. The model has as end product the expression level of a set of genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors). The level and stability of expression are a property of the regulatory interactions in the network. Le Rouzic made an important contribution to the study of such gene regulation models by using a quantitative genetics approach to the evolution of robustness. He crafted a way to assess the mutational variability and selection response of the components of robustness he was interested in. Le Rouzic’s approach opens avenues to investigate further aspects of gene network evolutionary properties, for instance to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Le Rouzic also discusses ways to measure his different robustness components in empirical studies. As the model is about gene expression levels at a set of protein-coding genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements, it naturally points to the possibility of using RNA sequencing to measure the variation of gene expression in know gene networks and assess their robustness. Robustness could then be studied as a multidimensional quantitative trait in an experimental setting. References [1] Le Rouzic, A (2022) Gene network robustness as a multivariate character. arXiv: 2101.01564, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564 [2] Waddington CH (1942) Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/150563a0 [3] Draghi J, Whitlock M (2015) Robustness to noise in gene expression evolves despite epistatic constraints in a model of gene networks. Evolution, 69, 2345–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12732 [4] Wagner A (1994) Evolution of gene networks by gene duplications: a mathematical model and its implications on genome organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 4387–4391. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.10.4387 | Gene network robustness as a multivariate character | Arnaud Le Rouzic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Robustness to genetic or environmental disturbances is often considered as a key property of living systems. Yet, in spite of being discussed since the 1950s, how robustness emerges from the complexity of genetic ar... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | Charles Mullon, Charles Rocabert, Diogo Melo | 2021-01-11 17:48:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer