Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

21 Nov 2022

Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughsElisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard https://doi.org/10.1101/679472The variety of bread-making practices promotes diversity conservation in food microbial communitiesRecommended by Tatiana Giraud and Jeanne Ropars based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDomesticated organisms are excellent models for understanding ecology and evolution and they are important for our food production and safety. While less studied than plants and animals, micro-organisms have also been domesticated, in particular for food fermentation [1]. The most studied domesticated micro-organism is the yeast used to make wine, beer and bread, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2, 3, 4]. Filamentous fungi used for cheese-making have recently gained interest, for example Penicillium roqueforti used to make blue cheeses and P. camemberti to make soft cheeses [5, 6, 7, 8]. As for plants and animals, domestication has led to beneficial traits for food production in fermenting fungi, but also to bottlenecks and degeneration [6, 7, 9]; P. camemberti for example does not produce enough spores any more for optimal culture and inoculation and P. roqueforti has lost sexual fertility [9]. The loss of genetic diversity and of species diversity in our food production system is concerning for multiple reasons : i) it jeopardizes future improvement in the face of global changes ; ii) it causes the loss of evolved diversity during centuries under human selection, and therefore of beneficial characteristics and specificities that we may never be able to recover ; iii) it leads to degeneration in the few cultivated strains; iv) it impoverishes the diversity of our food products and local adaptation of production practices. The study of domesticated fungi used for food fermentation has focused so far on the evolution of lineages and on their metabolic specificities. Microbiological assemblages and species diversity have been much less studied, while they likely also have a strong impact on the quality and safety of final products. This study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] addresses this question, using an interdisciplinary participatory research approach including bakers, psycho-sociologists and microbiologists to analyse bread-making practices and their impact on microbial communities in sourdough. Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] identified two distinct groups of bread-making practices based on interviews and surveys, with farmer-like practices (low bread production, use of ancient wheat populations, manual kneading, working at ambient temperature, long fermentation periods and no use of commercial baker’s yeast) versus more intensive, artisanal-like practices. Metabarcoding and microbial culture-based analyses showed that the well-known baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was, surprisingly, not the most common species in French organic sourdoughs. Kazachstania was the most represented yeast genus over all sourdoughs, both in terms of read abundance and of species diversity. Kazachstania species were also often dominant in individual sourdoughs, but Saccharomyces uvarum or Torulaspora delbrueckii could also be the dominant yeast species. Metabarcoding analyses further revealed that the composition of the fungal communities differed between the farmer-like and more intensive practices, representing the first evidence of the influence of artisanal practices on microbial communities. The fungal communities were impacted by a combination of bread-making variables including the type of wheat varieties, the length of fermentation, the quantity of bread made per week and the use of commercial yeast. Maintaining on farm less intensive bread-making practices, may allow the preservation of typical species and phenotypic diversity in microbial communities in sourdough. Farmer-like practices did not lead to higher diversity within sourdoughs but, overall, the diversity of bread-making practices allow maintaining a larger diversity in sourdoughs. For example, different Kazachstania species were most abundant in sourdoughs from artisanal-like and farmer-like practices. Interviews with the bakers suggested the role of dispersal of Kazachstania species in shaping sourdough microbial communities, dispersal occurring by seed exchanges, sourdough mixing or gifts, bread-making training in common or working in one another’s bakery. Nikolai Vavilov [11] had already highlighted for crops the importance of isolated cultures and selection in different farms for generating and preserving crop diversity, but also the importance of seed exchange for fostering adaptation. Furthermore, one of the yeast frequently found in artisanal sourdoughs, Kazachstania humilis, displayed phenotypic differences between sourdough and non-sourdough strains, suggesting domestication. The sourdough strains exhibited significantly higher CO2 production rate and a lower fermentation latency-phase time. The study by Elisa Michel and colleagues [10] is thus novel and inspiring in showing the importance of interdisciplinary studies, combining metabarcoding, microbiology and interviews for assessing the composition and diversity of microbial communities in human-made food, and in revealing the impact of artisanal-like bread-making practices in preserving microbial community diversity. Interdisciplinary studies are still rare but have already shown the importance of combining ethno-ecology, biology and evolution to decipher the role of human practices on genetic diversity in crops, animals and food microorganisms and to help preserving genetic resources [12]. For example, in the case of the bread wheat Triticum aestivum, such interdisciplinary studies have shown that genetic diversity has been shaped by farmers’ seed diffusion and farming practices [13]. We need more of such interdisciplinary studies on the impact of farmer versus industrial agricultural and food-making practices as we urgently need to preserve the diversity of micro-organisms used in food production that we are losing at a rapid pace [6, 7, 14]. References [1] Dupont J, Dequin S, Giraud T, Le Tacon F, Marsit S, Ropars J, Richard F, Selosse M-A (2017) Fungi as a Source of Food. Microbiology Spectrum, 5, 5.3.09. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0030-2016 [2] Legras J-L, Galeote V, Bigey F, Camarasa C, Marsit S, Nidelet T, Sanchez I, Couloux A, Guy J, Franco-Duarte R, Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T, Schuller D, Sampaio JP, Dequin S (2018) Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to Fermented Food Environments Reveals Remarkable Genome Plasticity and the Footprints of Domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1712–1727. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy066 [3] Bai F-Y, Han D-Y, Duan S-F, Wang Q-M (2022) The Ecology and Evolution of the Baker’s Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes, 13, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020230 [4] Fay JC, Benavides JA (2005) Evidence for Domesticated and Wild Populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics, 1, e5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0010005 [5] Ropars J, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, López-Villavicencio M, Gouzy J, Sallet E, Dumas É, Lacoste S, Debuchy R, Dupont J, Branca A, Giraud T (2015) Adaptive Horizontal Gene Transfers between Multiple Cheese-Associated Fungi. Current Biology, 25, 2562–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.025 [6] Dumas E, Feurtey A, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Le Prieur S, Snirc A, Coton M, Thierry A, Coton E, Le Piver M, Roueyre D, Ropars J, Branca A, Giraud T (2020) Independent domestication events in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti. Molecular Ecology, 29, 2639–2660. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15359 [7] Ropars J, Didiot E, Rodríguez de la Vega RC, Bennetot B, Coton M, Poirier E, Coton E, Snirc A, Le Prieur S, Giraud T (2020) Domestication of the Emblematic White Cheese-Making Fungus Penicillium camemberti and Its Diversification into Two Varieties. Current Biology, 30, 4441-4453.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.082 [8] Caron T, Piver ML, Péron A-C, Lieben P, Lavigne R, Brunel S, Roueyre D, Place M, Bonnarme P, Giraud T, Branca A, Landaud S, Chassard C (2021) Strong effect of Penicillium roqueforti populations on volatile and metabolic compounds responsible for aromas, flavor and texture in blue cheeses. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 354, 109174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109174 [9] Ropars J, Lo Y-C, Dumas E, Snirc A, Begerow D, Rollnik T, Lacoste S, Dupont J, Giraud T, López-Villavicencio M (2016) Fertility depression among cheese-making Penicillium roqueforti strains suggests degeneration during domestication. Evolution, 70, 2099–2109. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13015 [10] Michel E, Masson E, Bubbendorf S, Lapicque L, Nidelet T, Segond D, Guézenec S, Marlin T, Devillers H, Rué O, Onno B, Legrand J, Sicard D, Bakers TP (2022) Artisanal and farmer bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs. bioRxiv, 679472, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/679472 [11] Vavilov NI, Vavylov MI, Dorofeev VF (1992) Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. [12] Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Clarke AC (2013) Ethnobiology: the missing link in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.017 [13] Thomas M, Demeulenaere E, Dawson JC, Khan AR, Galic N, Jouanne-Pin S, Remoue C, Bonneuil C, Goldringer I (2012) On-farm dynamic management of genetic diversity: the impact of seed diffusions and seed saving practices on a population-variety of bread wheat. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00257.x [14] Demeulenaere É, Lagrola M (2021) Des indicateurs pour accompagner “ les éleveurs de microbes” : Une communauté épistémique face au problème des laits “ paucimicrobiens ” dans la production fromagère au lait cru (1995-2015). Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 15. http://journals.openedition.org/rac/24953 | Artisanal and farmers bread making practices differently shape fungal species community composition in French sourdoughs | Elisa Michel, Estelle Masson, Sandrine Bubbendorf, Leocadie Lapicque, Thibault Nidelet, Diego Segond, Stephane Guezenec, Therese Marlin, Hugo deVillers, Olivier Rue, Bernard Onno, Judith Legrand, Delphine Sicard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Preserving microbial diversity in food systems is one of the many challenges to be met to achieve food security and quality. Although industrialization led to the selection and spread of specific fermenting microbia... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Ecology | Tatiana Giraud | 2022-01-27 14:53:08 | View | |

18 Nov 2022

Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in PlasmodiumVilla M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478164The importance of understanding fitness costs associated with drug resistance throughout the life cycle of malaria parasitesRecommended by Silvie Huijben based on reviews by Sarah Reece and Marianna SzucsAntimalarial resistance is a major hurdle to malaria eradication efforts. The spread of drug resistance follows basic evolutionary principles, with competitive interactions between resistant and susceptible malaria strains being central to the fitness of resistant parasites. These competitive interactions can be used to design resistance management strategies, whereby a fitness cost of resistant parasites can be exploited through maintaining competitive suppression of the more fit drug-susceptible parasites. This can potentially be achieved using lower drug dosages or lower frequency of drug treatments. This approach has been demonstrated to work empirically in a rodent malaria model [1,2] and has been demonstrated to have clinical success in cancer treatments [3]. However, these resistance management approaches assume a fitness cost of the resistant pathogen, and, in the case of malaria parasites in general, and for artemisinin resistant parasites in particular, there is limited information on the presence of such fitness cost. The best suggestive evidence for the presence of fitness costs comes from the discontinuation of the use of the drug, which, in the case of chloroquine, was followed by a gradual drop in resistance frequency over the following decade [see e.g. 4,5]. However, with artemisinin derivative drugs still in use, alternative ways to study the presence of fitness costs need to be undertaken. References [1] Huijben S, Bell AS, Sim DG, Tomasello D, Mideo N, Day T, et al. 2013. Aggressive chemotherapy and the selection of drug resistant pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 9(9): e1003578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003578 [5] Mharakurwa S, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Mudare N, Matimba C, Gara TX, Makuwaza A, et al. 2021. Steep rebound of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 223(2): 306-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa368 | Fitness costs and benefits in response to artificial artesunate selection in Plasmodium | Villa M, Berthomieu A, Rivero A | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drug resistance is a major issue in the control of malaria. Mutations linked to drug resistance often target key metabolic pathways and are therefore expected to be associated with biological costs. The spread of dr... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Life History | Silvie Huijben | 2022-01-31 13:01:16 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View | |

24 Oct 2022

Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscuraAndres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.03.479001The other side of the evolution of heat tolerance: correlated responses in metabolism and life-history traitsRecommended by Inês Fragata and Pedro Simões based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marija Savić Veselinović and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding how species respond to environmental changes is becoming increasingly important in order to predict the future of biodiversity and species distributions under current global warming conditions (Rezende 2020; Bennett et al 2021). Two key factors to take into account in these predictions are the tolerance of organisms to heat stress and subsequently how they adapt to increasingly warmer temperatures. Coupled with this, one important factor that is often overlooked when addressing the evolution of thermal tolerance, is the correlated responses in traits that are important to fitness, such as life histories, behavior and the underlying metabolic processes. The rate and intensity of the thermal stress are expected to be major factors in shaping the evolution of heat tolerance and correlated responses in other traits. For instance, lower rates of thermal stress are predicted to select for individuals with a slower metabolism (Santos et al 2012), whereas low metabolism is expected to lead to a lower reproductive rate (Dammhahn et al 2018). To quantify the importance of the rate and intensity of thermal stress on the evolutionary response of heat tolerance and correlated response in behavior, Mesas et al (2021) performed experimental evolution in Drosophila subobscura using selective regimes with slow or fast ramping protocols. Whereas both regimes showed increased heat tolerance with similar evolutionary rates, the correlated responses in thermal performance curves for locomotor behavior differed between selection regimes. These findings suggest that thermal rate and intensity may shape the evolution of correlated responses in other traits, urging the need to understand possible correlated responses at relevant levels such as life history and metabolism. In the present contribution, Mesas and Castañeda (2022) investigate whether the disparity in thermal performance curves observed in the previous experiment (Mesas et al 2021) could be explained by differences in metabolic energy production and consumption, and how this correlated with the reproductive output (fecundity and viability). Overall, the authors show some evidence for lowered enzyme activity and increased performance in life-history traits, particularly for the slow-ramping selected flies. Specifically, the authors observe a reduction in glucose metabolism and increased viability when evolving under slow ramping stress. Interestingly, both regimes show a general increase in fecundity, suggesting that adaptation to these higher temperatures is not costly (for reproduction) in the ancestral environment. The evidence for a somewhat lower metabolism in the slow-ramping lines suggests the evolution of a slow “pace of life”. The “pace of life” concept tries to bridge variation across several levels namely metabolism, physiology, behavior and life history, with low “pace of life” organisms presenting lower metabolic rates, later reproduction and higher longevity than fast “pace of life” organisms (Dammhahn et al 2018, Tuzun & Stocks 2022). As the authors state there is not a clear-cut association with the expectations of the pace of life hypothesis since there was evidence for increased reproductive output under both selection intensity regimes. This suggests that, given sufficient trait genetic variance, positively correlated responses may emerge during some stages of thermal evolution. As fecundity estimates in this study were focussed on early life, the possibility of a decrease in the cumulative reproductive output of the selected flies, even under benign conditions, cannot be excluded. This would help explain the apparent paradox of increased fecundity in selected lines. In this context, it would also be interesting to explore the variation in reproductive output at different temperatures, i.e to obtain thermal performance curves for life histories. Mesas and Castañeda (2022) raise important questions to pursue in the future and contribute to the growing evidence that, in order to predict the distribution of ectothermic species under current global warming conditions, we need to expand beyond determining the physiological thermal limits of each organism (Parratt et al 2021). Ultimately, integrating metabolic, life-history and behavioral changes during evolution under different thermal stresses within a coherent framework is key to developing better predictions of temperature effects on natural populations. Bennett, J.M., Sunday, J., Calosi, P. et al. The evolution of critical thermal limits of life on Earth. Nat Commun 12, 1198 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21263-8 Dammhahn, M., Dingemanse, N.J., Niemelä, P.T. et al. Pace-of-life syndromes: a framework for the adaptive integration of behaviour, physiology and life history. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 72, 62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2473-y Mesas, A, Jaramillo, A, Castañeda, LE. Experimental evolution on heat tolerance and thermal performance curves under contrasting thermal selection in Drosophila subobscura. J Evol Biol 34, 767– 778 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13777 Parratt, S.R., Walsh, B.S., Metelmann, S. et al. Temperatures that sterilize males better match global species distributions than lethal temperatures. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 481–484 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01047-0 Santos, M, Castañeda, LE, Rezende, EL Keeping pace with climate change: what is wrong with the evolutionary potential of upper thermal limits? Ecology and evolution, 2(11), 2866-2880 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.385 Tüzün, N, Stoks, R. A fast pace-of-life is traded off against a high thermal performance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1972), 20212414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.2414 Rezende, EL, Bozinovic, F, Szilágyi, A, Santos, M. Predicting temperature mortality and selection in natural Drosophila populations. Science, 369(6508), 1242-1245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9287 | Evolutionary responses of energy metabolism, development, and reproduction to artificial selection for increasing heat tolerance in Drosophila subobscura | Andres Mesas, Luis E. Castaneda | <p>Adaptations to warming conditions exhibited by ectotherms include increasing heat tolerance but also metabolic changes to reduce maintenance costs (metabolic depression), which can allow them to redistribute the energy surplus to biological fun... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Life History | Inês Fragata | 2022-02-08 01:05:50 | View | |

24 Aug 2022

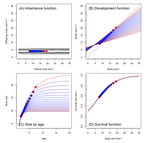

Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body sizeTim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952A population biological modeling approach for life history and body size evolutionRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Frédéric Guillaume and 2 anonymous reviewersBody size evolution is a central theme in evolutionary biology. Particularly the question of when and how smaller body sizes can evolve continues to interest evolutionary ecologists, because most life history models, and the empirical evidence, document that large body size is favoured by natural and sexual selection in most (even small) organisms and environments at most times. How, then, can such a large range of body size and life history syndromes evolve and coexist in nature? The paper by Coulson et al. lifts this question to the level of the population, a relatively novel approach using so-called integral projection (simulation) models (IPMs) (as opposed to individual-based or game theoretical models). As is well outlined by (anonymous) Reviewer 1, and following earlier papers spearheading this approach in other life history contexts, the authors use the well-known carrying capacity (K) of population biology as the ultimate fitness parameter to be maximized or optimized (rather than body size per se), to ultimately identify factors and conditions promoting the evolution of extreme body sizes in nature. They vary (individual or population) size-structured growth trajectories to observe age and size at maturity, surivorship and fecundity/fertility schedules upon evaluating K (see their Fig. 1). Importantly, trade-offs are introduced via density-dependence, either for adult reproduction or for juvenile survival, in two (of several conceivable) basic scenarios (see their Table 2). All other relevant standard life history variables (see their Table 1) are assumed density-independent, held constant or zero (as e.g. the heritability of body size). The authors obtain evidence for disruptive selection on body size in both scenarios, with small size and a fast life history evolving below a threshold size at maturity (at the lowest K) and large size and a slow life history beyond this threshold (see their Fig. 2). Which strategy wins ultimately depends on the fitness benefits of delaying sexual maturity (at larger size and longer lifespan) at the adult stage relative to the preceeding juvenile mortality costs, in agreement with classic life history theory (Roff 1992, Stearns 1992). The modeling approach can be altered and refined to be applied to other key life history parameters and environments. These results can ultimately explain the evolution of smaller body sizes from large body sizes, or vice versa, and their corresponding life history syndromes, depending on the precise environmental circumstances. All reviewers agreed that the approach taken is technically sound (as far as it could be evaluated), and that the results are interesting and worthy of publication. In a first round of reviews various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers. The new version was substantially changed by the authors in response, to the extent that it now is a quite different but much clearer paper with a clear message palatable for the general reader. The writing is now to the point, the paper's focus becomes clear in the Introduction, Methods & Results are much less technical, the Figures illustrative, and the descriptions and interpretations in the Discussion are easy to follow. In general any reader may of course question the choice and realism of the scenarios and underlying assumptions chosen by the authors for simplicity and clarity, for instance no heritability of body size and no cost of reproduction (other than mortality). But this is always the case in modeling work, and the authors acknowledge and in fact suggest concrete extensions and expansions of their approach in the Discussion. References Coulson T., Felmy A., Potter T., Passoni G., Montgomery R.A., Gaillard J.-M., Hudson P.J., Travis J., Bassar R.D., Tuljapurkar S., Marshall D.J., Clegg S.M. (2022) Density-dependent environments can select for extremes of body size. bioRxiv, 2022.02.17.480952, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.17.480952 | Density dependent environments can select for extremes of body size | Tim Coulson, Anja Felmy, Tomos Potter, Gioele Passoni, Robert A Montgomery, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Peter J Hudson, Joseph Travis, Ronald D Bassar, Shripad D Tuljapurkar, Dustin Marshall, Sonya M Clegg | <p>Body size variation is an enigma. We do not understand why species achieve the sizes they do, and this means we also do not understand the circumstances under which gigantism or dwarfism is selected. We develop size-structured integral projecti... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Theory, Life History | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2022-02-21 07:59:04 | View | |

15 Sep 2022

Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effectsHelene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784Spreading the risk of reproductive failure when the environment is unpredictable and ephemeralRecommended by Gabriele Sorci based on reviews by Thomas Haaland and Zoltan RadaiMany species breed in environments that are unpredictable, for instance in terms of the availability of resources needed to raise the offspring. Organisms might respond to such spatial and temporal unpredictability by adopting plastic responses to adjust their reproductive investment according to perceived cues of environmental quality. Some species such as the amphibians might also face the problem of ephemeral habitats, when the ponds where they breed have a chance of drying up before metamorphosis has occurred. In this case, maximizing long-term fitness might involve a strategy of spreading the risk, even though the reproductive success of a single reproductive bout might be lower. Understanding how animals (and plants) get adapted to stochastic environments is particularly crucial in the current context of rapid environmental changes. In this article, Jourdan-Pineau et al. report the results of field surveys of the Parsley Frog (Pelodytes punctatus) in Southern France. This frog has peculiar breeding phenology with females breeding in autumn and spring. The authors provide quite an extensive amount of information on the reproductive success of eggs laid in each season and the possible ecological factors accounting for differences between seasons. Although the presence of interspecific competitors and predators does not seem to account for pond-specific reproductive success, the survival of tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in spring is severely impaired when tadpoles from the autumn cohort have managed to survive. This intraspecific competition takes the form of a “priority” effect where tadpoles from the autumn cohort outcompete the smaller larvae from the spring cohort. Given this strong priority effect, one might tentatively predict that females laying in spring should avoid ponds with tadpoles from the autumn cohort. Surprisingly, however, the authors did not find any evidence for such avoidance, which might indicate strong constraints on the availability of ponds where females might possibly lay. Assuming that each female can indeed lay both in autumn and spring, how is this bimodal phenology maintained? Would not be worthier to allocate all the eggs to the autumn (or the spring) laying season? Eggs laid in autumn and spring have to face different environmental hazards, reducing their hatching success and the probability to produce metamorphs (for instance, tadpoles hatching from eggs laid in autumn have to overwinter which might be a particularly risky phase). Jourdan-Pineau and coworkers addressed this question by adapting a bet-hedging model that was initially developed to investigate the strategy of allocation into seed dormancy of annual plants (Cohen 1966) to the case of the bimodal phenology of the Parsley Frog. By feeding the model with the parameter values obtained from the field surveys, they found that the two breeding strategies (laying in autumn and in spring) can coexist as long as the probability of breeding success in the autumn cohort is between 20% and 80% (the range of values allowing the coexistence of a bimodal phenology shrinking a little bit when considering that frogs can reproduce 5 times during their lifespan instead of three times). This paper provides a very nice illustration of the importance of combining approaches (here field monitoring to gather data that can be used to feed models) to understand the evolution of peculiar breeding strategies. Although future work should attempt to gather individual-based data (in addition to population data), this work shows that spreading the risk can be an adaptive strategy in environments characterized by strong stochastic variation. References Cohen D (1966) Optimizing reproduction in a randomly varying environment. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 12, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90188-3 Jourdan-Pineau H., Crochet P.-A., David P. (2022) Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects. bioRxiv, 2022.02.24.481784, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.24.481784 | Bimodal breeding phenology in the Parsley Frog Pelodytes punctatus as a bet-hedging strategy in an unpredictable environment despite strong priority effects | Helene Jourdan-Pineau, Pierre-Andre Crochet, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">When environmental conditions are unpredictable, expressing alternative phenotypes spreads the risk of failure, a mixed strategy called bet-hedging. In the southern part of its range, the Parsley Frog <em>Pelodytes ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Life History | Gabriele Sorci | 2022-02-28 11:53:00 | View | |

22 Feb 2023

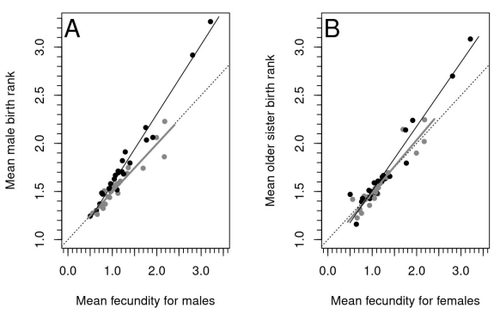

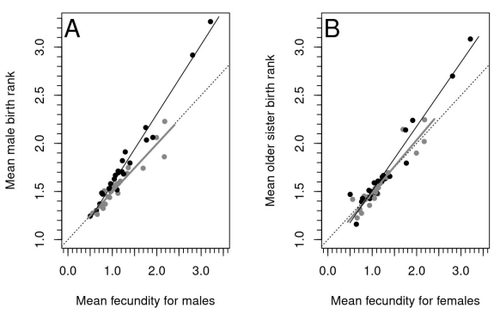

Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesisMichel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477Evolutionary or proximal explanations for human male homosexual mate preference?Recommended by Jacqui A. Shykoff based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ray Blanchard and 1 anonymous reviewer

Natural populations do not consist of only perfectly adapted individuals. If they did, of course, there would be no fodder for evolution by natural selection. And natural selection is operating all the time, winnowing out less well adapted phenotypes through differential reproduction and survival. Demonstrations of natural selection modifying characters-state distributions to bring phenotypes closer to their optima abound in the evolution literature, with examples of short- and long-term changes in phenotype and allele frequencies. However, evolutionary biologists know that populations cannot reach their adaptive peaks. Natural selection is tracking a moving target, always with some generations of lag time. The adaptive landscape is multidimensional, so the optimal combination of multiple character states may be impossible because of constraints and trade-offs. Natural selection does not operate alone or in isolation – new mutations and migrants that were selected under other conditions will inject locally non-adaptive genetic variation and genetic drift can change allele frequencies in random directions. We understand these processes that generate and maintain less advantageous variants on a continuous gradient from an optimal phenotype in a fitness landscape. More puzzling are heritable polymorphisms with distinct morphologies, physiologies or behaviours maintained in populations despite their measurably lower reproductive success. But a complete model of evolution must also be able to accommodate these Darwinian paradoxes. Raymond et al. (2023) investigate one such Darwinian paradox: In humans, male homosexual mate preference is heritable and is associated with a large reduction in offspring production but nonetheless occurs at relatively high frequencies in most human populations. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that homosexual men come from families that are, on average, larger than those of heterosexual men and that homosexual men have, on average, higher birth rank than do heterosexual men, i.e., having more older siblings and, particularly, more older brothers. Two types of mechanisms consistent with these observations have been proposed: 1) An evolutionary mechanism of sex-antagonistic pleiotropy, whereby highly fecund mothers are more likely to produce homosexual sons, and 2) A mechanistic explanation whereby successive male pregnancies alter the uterine environment by increasing the probability of an immune reaction by the mother to her male fetus, altering development of sexually dimorphic brain structures relevant to sexual orientation. In this article, the authors explore these two mechanisms of sex-antagonistic effects (AE) and fraternal birth order effects (FBOE) and test how well they account for patterns of male homosexuality in population and family data. Clearly, these two effects are somewhat confounded because high birth ranks can only occur in large families. If, indeed, the probability of male homosexuality increases with increasing numbers of (maternal) older brothers, homosexual males will be more common in larger families. Similarly, if high female fecundity leads to a higher probability of male homosexuality via sex-antagonistic effects, homosexual males will, on average, have more older brothers. To disentangle the actions of these two effects the authors modelled the relationship between birth rank and population fecundity and investigated whether AE or FBOE modified this relationship for homosexual men. Simulation results were compared with aggregated population data from 13 countries. Family data on individuals’ sexual preference, birth rank and number of male and female siblings from France, Greece and Indonesia were analysed with generalised linear models and Bayesian approaches to test for a signal of AE or FBOE. These analyses revealed a significant older-brother effect (FBOE) explaining patterns of occurrence of homosexuality in population and family data but no significant independent sex-antagonistic effect (AE). Thus larger family sizes of homosexual men appear due to the older-brother effect, with individuals of high birth rank coming necessarily from large sibships. The simulation approach also revealed that modelling a fraternal birth order effect (FBOE), such that individuals with more older brothers are more likely to be homosexual, generates an artefactual older sister effect simply because homosexual men are overrepresented at higher birth ranks. Older-sister effects reported in the literature may, therefore, be statistical artefacts of an underlying older-brother effect. This paper is interesting for a number of reasons. It does an excellent job of explaining, identifying and dealing with estimation biases and testing for artefactual relationships generated by collinearity. It applies state-of-the art analytical/statistical tools. It breaks down two colinear effects and shows that only one really explains phenotypic variation. This is a great example of how to disentangle correlated variables that may or may not both contribute to trait variation. But most intriguingly, we are left without evidence for an evolutionary mechanism that compensates the large fitness cost associated with male homosexuality in humans. How can we explain high heritability maintained in the face of strong directional selection that should erode heritable genetic variation? The usual suspects include cryptic compensatory mechanisms yet to be discovered or flawed estimates of selection or heritability. For example, data on heritability of male homosexual mate preference in humans come from twin studies and twins share birth rank as well as alleles. Thus it is possible that heritability is over-estimated, including the environmental component associated with birth rank. If, as the authors demonstrate here, birth rank is the strongest predictor of male homosexual mate preference, selection may be acting on a non-heritable plastic component of phenotypic variation. This could explain why heritable variation is not exhausted by selection, rendering the paradox less paradoxical, but fails to provide an adaptive explanation for the maintenance of male homosexual mate preference. References Raymond M., Turek D., Durand V., Nila S., Suryobroto B., Vadez J., Barthes J., Apostolou M. and Crochet P.-A. (2023) Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis. bioRxiv, 2022.02.22.481477, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481477 | Increased birth rank of homosexual males: disentangling the older brother effect and sexual antagonism hypothesis | Michel Raymond, Daniel Turek, Valerie Durand, Sarah Nila, Bambang Suryobroto, Julien Vadez, Julien Barthes, Menelaos Apostolou, Pierre-André Crochet | <p style="text-align: justify;">Male homosexual orientation remains a Darwinian paradox, as there is no consensus on its evolutionary (ultimate) determinants. One intriguing feature of homosexual men is their higher male birth rank compared to het... |  | Life History, Other, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex | Jacqui A. Shykoff | 2022-03-03 11:28:44 | View | |

05 Oct 2022

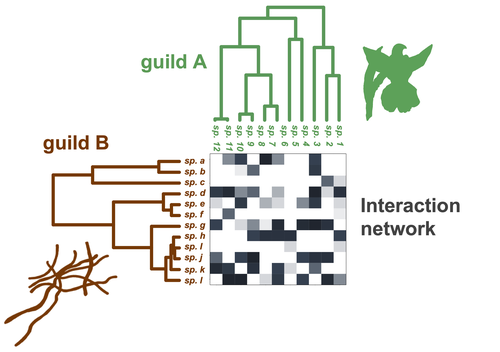

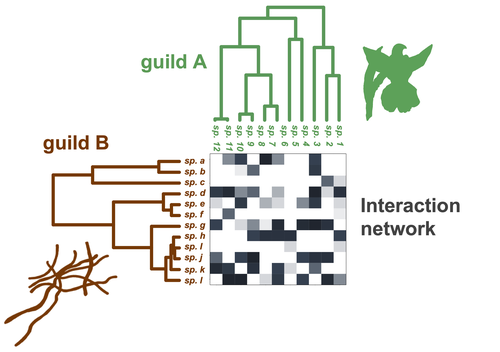

Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networksBenoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192Testing for phylogenetic signal in species interaction networksRecommended by Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer based on reviews by Joaquin Calatayud and Thomas GuillermeSpecies are immersed within communities in which they interact mutualistically, as in pollination or seed dispersal, or nonreciprocally, such as in predation or parasitism, with other species and these interactions play a paramount role in shaping biodiversity (Bascompte and Jordano 2013). Researchers have become increasingly interested in the processes that shape these interactions and how these influence community structure and responses to disturbances. Species interactions are often described using bipartite interaction networks and one important question is how the evolutionary history of the species involved influences the network, including whether there is phylogenetic signal in interactions, in other words whether closely related species interact with other closely related species (Bascompte and Jordano 2013, Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022). To address this question different approaches, correlative and model-based, have been developed to test for phylogenetic signal in interactions, although comparative analyses of the performance of these different metrics are lacking. In their article Perez-Lamarque et al. (2022) set out to test the statistical performance of two widely-used methods, Mantel tests and Phylogenetic Bipartite Linear Models (PBLM; Ives and Godfray 2006) using simulations. Phylogenetic signal is measured as the degree to which distance to the nearest common ancestor predicts the observed similarity in trait values among species. In species interaction networks, the data are actually the between-species dissimilarity among interacting species (Perez-Lamarque et al. 2022), and typical approaches to test for phylogenetic signal cannot be used. However, the Mantel test provides a useful means of analyzing the correlation between two distance matrices, the between-species phylogenetic distance and the between-species dissimilarity in interactions. The PBLM approach, on the other hand, assumes that interactions between species are influenced by unobserved traits that evolve along the phylogenies following a given phenotypic evolution model and the parameters of this model are interpreted in terms of phylogenetic signal (Ives and Godfray 2006). Perez-Lamarque et al (2022) found that the model-based PBLM approach has a high type-I error rate, in other words it often detected phylogenetic signal when there was none. The simple Mantel test was found to present a low type-I error rate and moderate statistical power. However, it tended to overestimate the degree to which species interact with dissimilar partners. In addition to the aforementioned analyses, the authors also tested whether the simple Mantel test was able to detect phylogenetic signal in interactions among species within a given clade in the phylogeny, as phylogenetic signal in species interactions may be localized within specific clades. The article concludes with general guidelines for users wishing to test phylogenetic signal in their interaction networks and illustrates them with an example of an orchid-mycorrhizal fungus network from the oceanic island of La Réunion (Martos et al 2012). This broadly accessible article provides a valuable analysis of the performance of tests of phylogenetic signal in interaction networks enabling users to make informed choices of the analytical methods they wish to employ, and provide useful and detailed guidelines. Therefore, the work should be of broad interest to researchers studying species interactions. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400848720 Ives AR, Godfray HCJ (2006) Phylogenetic Analysis of Trophic Associations. The American Naturalist, 168, E1–E14. https://doi.org/10.1086/505157 Martos F, Munoz F, Pailler T, Kottke I, Gonneau C, Selosse M-A (2012) The role of epiphytism in architecture and evolutionary constraint within mycorrhizal networks of tropical orchids. Molecular Ecology, 21, 5098–5109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05692.x Perez-Lamarque B, Maliet O, Pichon B, Selosse M-A, Martos F, Morlon H (2022) Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks. bioRxiv, 2021.08.30.458192, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.30.458192 | Do closely related species interact with similar partners? Testing for phylogenetic signal in bipartite interaction networks | Benoît Perez-Lamarque, Odile Maliet, Benoît Pichon, Marc-André Selosse, Florent Martos, Hélène Morlon | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whether interactions between species are conserved on evolutionary time-scales has spurred the development of both correlative and process-based approaches for testing phylogenetic signal in interspecific interactio... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Species interactions | Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer | 2022-03-10 13:48:15 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

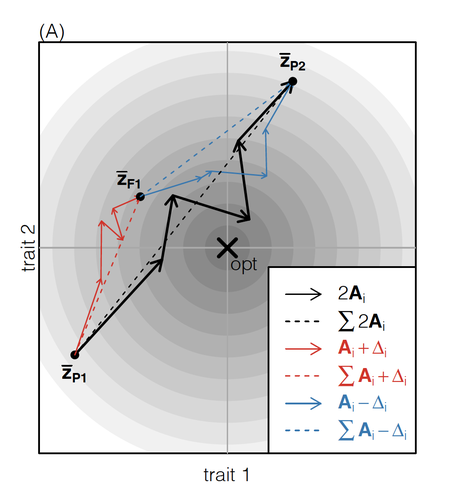

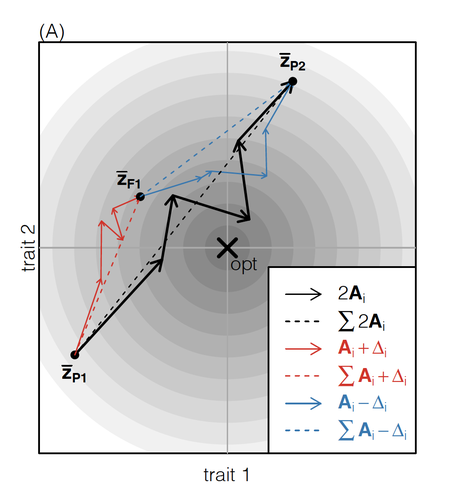

How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation?Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483443A general model of fitness effects following hybridisationRecommended by Matthew Hartfield based on reviews by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Juan LiStudying the effects of speciation, hybridisation, and evolutionary outcomes following reproduction from divergent populations is a major research area in evolutionary genetics [1]. There are two phenomena that have been the focus of contemporary research. First, a classic concept is the formation of ‘Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller’ incompatibilities (BDMi) [2–4] that negatively affect hybrid fitness. Here, two diverging populations accumulate mutations over time that are unique to that subpopulation. If they subsequently meet, then these mutations might negatively interact, leading to a loss in fitness or even a complete lack of reproduction. BDMi formation can be complex, involving multiple genes and the fitness changes can depend on the direction of introgression [5]. Second, such secondary contact can instead lead to heterosis, where offspring are fitter than their parental progenitors [6]. Understanding which outcomes are likely to arise require one to know the potential fitness effects of mutations underlying reproductive isolation, to determine whether they are likely to reduce or enhance fitness when hybrids are formed. This is far from an easy task, as it requires one to track mutations at several loci, along with their effects, across a fitness landscape. The work of De Sanctis et al. [7] neatly fills in this knowledge gap, by creating a general mathematical framework for describing the consequences of a cross from two divergent populations. The derivations are based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, which is widely used to quantify selection acting on a general fitness landscape that is affected by several biological traits [8,9], and has previously been used in theoretical studies of hybridisation [10–12]. By doing so, they are able to decompose how divergence at multiple loci affects offspring fitness through both additive and dominance effects. A key result arising from their analyses is demonstrating how offspring fitness can be captured by two main functions. The first one is the ‘net effect of evolutionary change’ that, broadly defined, measures how phenotypically divergent two populations are. The second is the ‘total amount of evolutionary change’, which reflects how many mutations contribute to divergence and the effect sizes captured by each of them. The authors illustrate these measurements using simulations covering different scenarios, demonstrating how different parental states can lead to similar fitness outcomes. They also propose experimental methods to measure the underlying mutational effects. This study neatly demonstrates how complex genetic phenomena underlying hybridisation can be captured using fairly simple mathematical formulae. This powerful approach will thus open the door for future research to investigate hybridisation in more detail, whether it is by expanding on these theoretical models or using the elegant outcomes to quantify fitness effects in experiments.

References 1. Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2004. | How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation? | Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch | <p>When divergent populations interbreed, the outcome will be affected by the genomic and phenotypic differences that they have accumulated. In this way, the mode of evolutionary divergence between populations may have predictable consequences for... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Matthew Hartfield | 2022-03-30 14:55:46 | View | |

31 Oct 2022

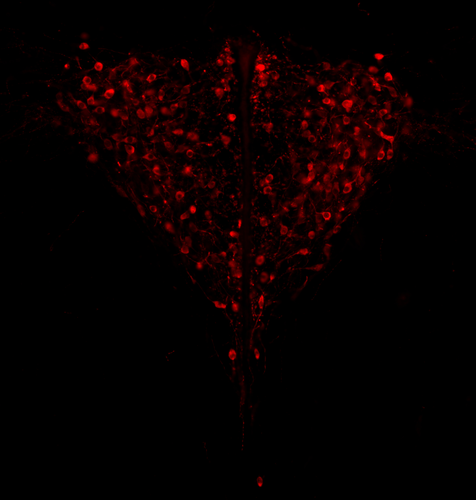

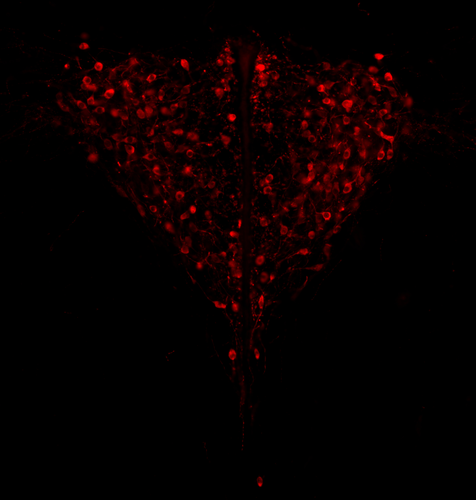

Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoidesLouise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174Effect of sex chromosomes on mammalian behaviour: a case study in pygmy miceRecommended by Gabriel Marais and Trine Bilde based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Marion Anne-Lise Picard, Caroline Hu and 1 anonymous reviewer

In mammals, it is well documented that sexual dimorphism and in particular sex differences in behaviour are fine-tuned by gonadal hormonal profiles. For example, in lemurs, where female social dominance is common, the level of testosterone in females is unusually high compared to that of other primate females (Petty and Drea 2015). Recent studies however suggest that gonadal hormones might not be the only biological factor involved in establishing sexual dimorphism, sex chromosomes might also play a role. The four core genotype (FCG) model and other similar systems allowing to decouple phenotypic and genotypic sex in mice have provided very convincing evidence of such a role (Gatewood et al. 2006; Arnold and Chen 2009; Arnold 2020a, 2020b). This however is a new field of research and the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sexually dimorphic behaviours has not been studied very much yet. Moreover, the FCG model has some limits. Sry, the male determinant gene on the mammalian Y chromosome might be involved in some sex differences in neuroanatomy, but Sry is always associated with maleness in the FCG model, and this potential role of Sry cannot be studied using this system. Heitzmann et al. have used a natural system to approach these questions. They worked on the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides, in which a modified X chromosome called X* can feminize X*Y individuals, which offers a great opportunity for elegant experiments on the effects of sex chromosomes versus hormones on behaviour. They focused on maternal care and compared pup retrieval, nest quality, and mother-pup interactions in XX, X*X and X*Y females. They found that X*Y females are significantly better at retrieving pups than other females. They are also much more aggressive towards the fathers than other females, preventing paternal care. They build nests of poorer quality but have similar interactions with pups compared to other females. Importantly, no significant differences were found between XX and X*X females for these traits, which points to an effect of the Y chromosome in explaining the differences between X*Y and other females (XX, X*X). Also, another work from the same group showed similar gonadal hormone levels in all the females (Veyrunes et al. 2022). Heitzmann et al. made a number of predictions based on what is known about the neuroanatomy of rodents which might explain such behaviours. Using cytology, they looked for differences in neuron numbers in the hypothalamus involved in the oxytocin, vasopressin and dopaminergic pathways in XX, X*X and X*Y females, but could not find any significant effects. However, this part of their work relied on very small sample sizes and they used virgin females instead of mothers for ethical reasons, which greatly limited the analysis. Interestingly, X*Y females have a higher reproductive performance than XX and X*X ones, which compensate for the cost of producing unviable YY embryos and certainly contribute to maintaining a high frequency of X* in many African pygmy mice populations (Saunders et al. 2014, 2022). X*Y females are probably solitary mothers contrary to other females, and Heitzmann et al. have uncovered a divergent female strategy in this species. Their work points out the role of sex chromosomes in establishing sex differences in behaviours. References Arnold AP (2020a) Sexual differentiation of brain and other tissues: Five questions for the next 50 years. Hormones and Behavior, 120, 104691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104691 Arnold AP (2020b) Four Core Genotypes and XY* mouse models: Update on impact on SABV research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 119, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.021 Arnold AP, Chen X (2009) What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001 Gatewood JD, Wills A, Shetty S, Xu J, Arnold AP, Burgoyne PS, Rissman EF (2006) Sex Chromosome Complement and Gonadal Sex Influence Aggressive and Parental Behaviors in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3743-05.2006 Heitzmann LD, Challe M, Perez J, Castell L, Galibert E, Martin A, Valjent E, Veyrunes F (2022) Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides. bioRxiv, 2022.04.05.487174, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.05.487174 Petty JMA, Drea CM (2015) Female rule in lemurs is ancestral and hormonally mediated. Scientific Reports, 5, 9631. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09631 Saunders PA, Perez J, Rahmoun M, Ronce O, Crochet P-A, Veyrunes F (2014) Xy Females Do Better Than the Xx in the African Pygmy Mouse, Mus Minutoides. Evolution, 68, 2119–2127. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12387 Saunders PA, Perez J, Ronce O, Veyrunes F (2022) Multiple sex chromosome drivers in a mammal with three sex chromosomes. Current Biology, 32, 2001-2010.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.03.029 Veyrunes F, Perez J, Heitzmann L, Saunders PA, Givalois L (2022) Separating the effects of sex hormones and sex chromosomes on behavior in the African pygmy mouse Mus minutoides, a species with XY female sex reversal. bioRxiv, 2022.07.11.499546. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.11.499546 | Genotypic sex shapes maternal care in the African Pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides | Louise D Heitzmann, Marie Challe, Julie Perez, Laia Castell, Evelyne Galibert, Agnes Martin, Emmanuel Valjent, Frederic Veyrunes | <p>Sexually dimorphic behaviours, such as parental care, have long been thought to be driven mostly, if not exclusively, by gonadal hormones. In the past two decades, a few studies have challenged this view, highlighting the direct influence of th... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | 2022-04-08 20:09:58 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer