Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 May 2020

When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue?Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl https://doi.org/10.1101/622142Reconciling the upsides and downsides of migration for evolutionary rescueRecommended by Claudia Bank based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThe evolutionary response of populations to changing or novel environments is a topic that unites the interests of evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and biomedical researchers [1]. A prominent phenomenon in this research area is evolutionary rescue, whereby a population that is otherwise doomed to extinction survives due to the spread of new or pre-existing mutations that are beneficial in the new environment. Scenarios of evolutionary rescue require a specific set of parameters: the absolute growth rate has to be negative before the rescue mechanism spreads, upon which the growth rate becomes positive. However, potential examples of its relevance exist (e.g., [2]). From a theoretical point of view, the technical challenge but also the beauty of evolutionary rescue models is that they combine the study of population dynamics (i.e., changes in the size of populations) and population genetics (i.e., changes in the frequencies in the population). Together, the potential relevance of evolutionary rescue in nature and the models' theoretical appeal has resulted in a suite of modeling studies on the subject in recent years. References [1] Bell, G. (2017). Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48(1), 605-627. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | When does gene flow facilitate evolutionary rescue? | Matteo Tomasini, Stephan Peischl | <p>Experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the impact of gene flow on the probability of evolutionary rescue in structured habitats. Mathematical modelling and simulations of evolutionary rescue in spatially or otherwise structured p... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Claudia Bank | 2019-05-22 11:12:13 | View | |

26 Oct 2020

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing populationMiguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populationsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1]. References [1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14 | Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View | |

12 Jun 2017

Modelling the evolution of how vector-borne parasites manipulate the vector's host choiceRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and Nicole Mideo

Many parasites can manipulate their hosts, thus increasing their transmission to new hosts [1]. This is particularly the case for vector-borne parasites, which can alter the feeding behaviour of their hosts. However, predicting the optimal strategy is not straightforward because three actors are involved and the interests of the parasite may conflict with that of the vector. There are few models that consider the evolution of host manipulation by parasites [but see 2-4], but there are virtually none that investigated how parasites can manipulate the host choice of vectors. Even on the empirical side, many aspects of this choice remain unknown. Gandon [5] develops a simple evolutionary epidemiology model that allows him to formulate clear and testable predictions. These depend on which actor controls the trait (the vector or the parasite) and, when there is manipulation, whether it is realised via infected hosts (to attract vectors) or infected vectors (to change host choice). In addition to clarifying the big picture, Gandon [5] identifies some nice properties of the model, for instance an independence of the density/frequency-dependent transmission assumption or a backward bifurcation at R0=1, which suggests that parasites could persist even if their R0 is driven below unity. Overall, this study calls for further investigation of the different scenarios with more detailed models and experimental validation of general predictions. References [1] Hughes D, Brodeur J, Thomas F. 2012. Host manipulation by parasites. Oxford University Press. [2] Brown SP. 1999. Cooperation and conflict in host-manipulating parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 266: 1899–1904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0864 [3] Lion S, van Baalen M, Wilson WG. 2006. The evolution of parasite manipulation of host dispersal. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 273: 1063–1071. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3412 [4] Vickery WL, Poulin R. 2010. The evolution of host manipulation by parasites: a game theory analysis. Evolutionary Ecology 24: 773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10682-009-9334-0 [5] Gandon S. 2017. Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice. bioRxiv 110577, ver. 3 of 7th June 2017. doi: 10.1101/110577 | Evolution and manipulation of vector host choice | Sylvain Gandon | The transmission of many animal and plant diseases relies on the behavior of arthropod vectors. In particular, the choice to feed on either infected or uninfected hosts can dramatically affect the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases. I develop a... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2017-03-03 19:18:54 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation?Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483443A general model of fitness effects following hybridisationRecommended by Matthew Hartfield based on reviews by Luis-Miguel Chevin and Juan LiStudying the effects of speciation, hybridisation, and evolutionary outcomes following reproduction from divergent populations is a major research area in evolutionary genetics [1]. There are two phenomena that have been the focus of contemporary research. First, a classic concept is the formation of ‘Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller’ incompatibilities (BDMi) [2–4] that negatively affect hybrid fitness. Here, two diverging populations accumulate mutations over time that are unique to that subpopulation. If they subsequently meet, then these mutations might negatively interact, leading to a loss in fitness or even a complete lack of reproduction. BDMi formation can be complex, involving multiple genes and the fitness changes can depend on the direction of introgression [5]. Second, such secondary contact can instead lead to heterosis, where offspring are fitter than their parental progenitors [6]. Understanding which outcomes are likely to arise require one to know the potential fitness effects of mutations underlying reproductive isolation, to determine whether they are likely to reduce or enhance fitness when hybrids are formed. This is far from an easy task, as it requires one to track mutations at several loci, along with their effects, across a fitness landscape. The work of De Sanctis et al. [7] neatly fills in this knowledge gap, by creating a general mathematical framework for describing the consequences of a cross from two divergent populations. The derivations are based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, which is widely used to quantify selection acting on a general fitness landscape that is affected by several biological traits [8,9], and has previously been used in theoretical studies of hybridisation [10–12]. By doing so, they are able to decompose how divergence at multiple loci affects offspring fitness through both additive and dominance effects. A key result arising from their analyses is demonstrating how offspring fitness can be captured by two main functions. The first one is the ‘net effect of evolutionary change’ that, broadly defined, measures how phenotypically divergent two populations are. The second is the ‘total amount of evolutionary change’, which reflects how many mutations contribute to divergence and the effect sizes captured by each of them. The authors illustrate these measurements using simulations covering different scenarios, demonstrating how different parental states can lead to similar fitness outcomes. They also propose experimental methods to measure the underlying mutational effects. This study neatly demonstrates how complex genetic phenomena underlying hybridisation can be captured using fairly simple mathematical formulae. This powerful approach will thus open the door for future research to investigate hybridisation in more detail, whether it is by expanding on these theoretical models or using the elegant outcomes to quantify fitness effects in experiments.

References 1. Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2004. | How does the mode of evolutionary divergence affect reproductive isolation? | Bianca De Sanctis, Hilde Schneemann, John J. Welch | <p>When divergent populations interbreed, the outcome will be affected by the genomic and phenotypic differences that they have accumulated. In this way, the mode of evolutionary divergence between populations may have predictable consequences for... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Theory, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation | Matthew Hartfield | 2022-03-30 14:55:46 | View | |

15 Feb 2019

Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approachRubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez https://doi.org/10.1101/356147Sometimes, sex is in the headRecommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Plants display an amazing diversity of reproductive strategies with and without sex. This diversity is particularly remarkable in flowering plants, as highlighted by Charles Darwin, who wrote several botanical books scrutinizing plant reproduction. One particularly influential work concerned floral variation [1]. Darwin recognized that flowers may present different forms within a single population, with or without sex specialization. The number of species concerned is small, but they display recurrent patterns, which made it possible for Darwin to invoke natural and sexual selection to explain them. Most of early evolutionary theory on the evolution of reproductive strategies was developed in the first half of the 20th century and was based on animals. However, the pioneering work by David Lloyd from the 1970s onwards excited interest in the diversity of plant sexual strategies as models for testing adaptive hypotheses and predicting reproductive outcomes [2]. The sex specialization of individual flowers and plants has since become one of the favorite topics of evolutionary biologists. However, attention has focused mostly on cases related to sex differentiation (dioecy and associated conditions [3]). Separate unisexual flower types on the same plant (monoecy and related cases, rendering the plant functionally hermaphroditic) have been much less studied, apart from their possible role in the evolution of dioecy [4] or their association with particular modes of pollination [5]. References [1] Darwin, C. (1877). The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. John Murray. | Architectural traits constrain the evolution of unisexual flowers and sexual segregation within inflorescences: an interspecific approach | Rubén Torices, Ana Afonso, Arne A. Anderberg, José M. Gómez and Marcos Méndez | <p>Male and female unisexual flowers have repeatedly evolved from the ancestral bisexual flowers in different lineages of flowering plants. This sex specialization in different flowers often occurs within inflorescences. We hypothesize that inflor... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Morphological Evolution, Phenotypic Plasticity, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Juan Arroyo | Jana Vamosi, Marcial Escudero, Anonymous | 2018-06-27 10:49:52 | View |

16 Mar 2023

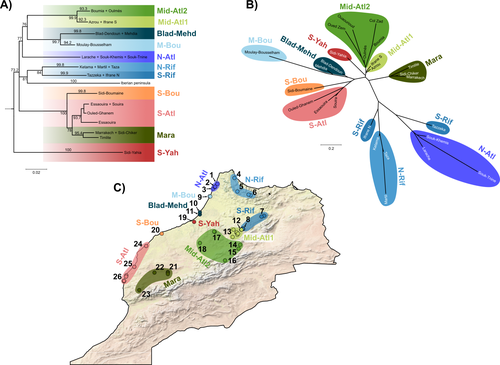

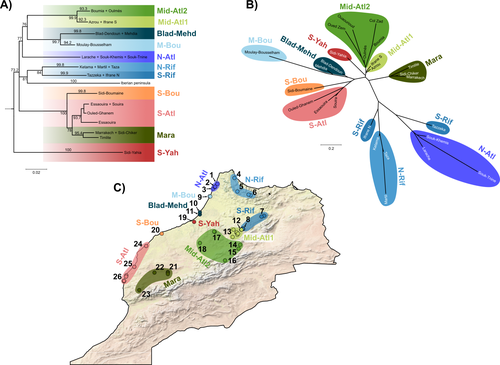

Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersalLoïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256The difficult task of partitioning the effects of vicariance and isolation by distance in poor dispersersRecommended by Eric Pante based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou based on reviews by Kevin Sánchez and Aglaia (Cilia) Antoniou

Partitioning the effects of vicariance and low dispersal has been a long-standing problem in historical biogeography and phylogeography. While the term “vicariance” refers to divergence in allopatry, caused by some physical (geological, geographical) or climatic barriers (e.g. Rosen 1978), isolation by distance refers to the genetic differentiation of remote populations due to the physical distance separating them, when the latter surpasses the scale of dispersal (Wright 1938, 1940, 1943). Vicariance and dispersal have long been considered as separate forces leading to separate scenarii of speciation (e.g. reviewed in Hickerson and Meyer 2008). Nevertheless, these two processes are strongly linked, as, for example, vicariance theory relies on the assumption that ancestral lineages were once linked by dispersal prior to physical or climatic isolation (Rosen 1978). Low dispersal and vicariance are not mutually exclusive, and distinguishing these two processes in heterogeneous landscapes, especially for poor dispersers, remains therefore a severe challenge. For example, low dispersal (and/or small population size) can give rise to geographic patterns consistent with a phylogeographic break and be mistaken for geographic isolation (Irwin 2002, Kuo and Avise 2005). The study of Rancilliac and colleagues (2023) is at the heart of this issue. It focuses on a nominal lizard species, the red-tailed spiny-footed lizard (Acanthodactylus erythrurus, Squamata: Lacertidae), which has a wide spatial distribution (from the Maghreb to the Iberian Peninsula), is found in a variety of different habitats, and has a wide range of morphological traits that do not always correlate with phylogeny. The main question is the following: have “the morphological and ecological diversification of this group been produced by vicariance and lineage diversification, or by local adaptation in the face of historical gene flow?” To tackle this question, the authors used sequence data from multiple mitochondrial and nuclear markers and a nested analysis workflow integrating phylogeography, multiple correspondence analyses and a relatively novel approach to IBD testing (Hausdorf & Henning, 2020). The latter is based on regression analysis and was shown to be less prone to error than the traditional (partial) Mantel test. While this set of methods allowed the partitioning of the effect of isolation by distance and vicariance in shaping contemporary genetic diversity in red-tailed spiny-footed lizards, some of the evolutionary history of this species complex remains blurred by ongoing gene flow and admixture, retention of ancestral polymorphism, or selection. The lack of congruence between mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees once again warns us that proposing evolutionary scenarii based on individual gene trees is a risky business. References Hausdorf B, Hennig C (2020) Species delimitation and geography. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20, 950–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13184 Hickerson MJ, Meyer CP (2008) Testing comparative phylogeographic models of marine vicariance and dispersal using a hierarchical Bayesian approach. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 8, 322. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-322 Irwin DE (2002) Phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers to gene flow. Evolution, 56, 2383–2394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00164.x Kuo C-H, Avise JC (2005) Phylogeographic breaks in low-dispersal species: the emergence of concordance across gene trees. Genetica, 124, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10709-005-2095-y Rancilhac L, Miralles A, Geniez P, Mendez-Aranda D, Beddek M, Brito JC, Leblois R, Crochet P-A (2023) Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: An empirical attempt at separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal. bioRxiv, 2022.09.30.510256, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.30.510256 Rosen DE (1978) Vicariant Patterns and Historical Explanation in Biogeography. Systematic Biology, 27, 159–188. https://doi.org/10.2307/2412970 Wright, S (1938) Size of population and breeding structure in relation to evolution. Science 87:430-431. Wright S (1940) Breeding Structure of Populations in Relation to Speciation. The American Naturalist, 74, 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/280891 Wright S (1943) Isolation by distance. Genetics, 28, 114–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/28.2.114 | Phylogeographic breaks and how to find them: Separating vicariance from isolation by distance in a lizard with restricted dispersal | Loïs Rancilhac, Aurélien Miralles, Philippe Geniez, Daniel Mendez-Arranda, Menad Beddek, José Carlos Brito, Raphaël Leblois, Pierre-André Crochet | <p>Aim</p> <p>Discontinuity in the distribution of genetic diversity (often based on mtDNA) is usually interpreted as evidence for phylogeographic breaks, underlying vicariant units. However, a misleading signal of phylogeographic break can arise... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Speciation, Systematics / Taxonomy | Eric Pante | Kevin Sánchez | 2022-10-05 13:11:28 | View |

13 Dec 2018

A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid waspsD. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi https://doi.org/10.1101/342758Genetic intimacy of filamentous viruses and endoparasitoid waspsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Alejandro Manzano Marín and 1 anonymous reviewerViruses establish intimate relationships with the cells they infect. The virocell is a novel entity, different from the original host cell and beyond the mere combination of viral and cellular genetic material. In these close encounters, viral and cellular genomes often hybridise, combine, recombine, merge and excise. Such chemical promiscuity leaves genomics scars that can be passed on to descent, in the form of deletions or duplications and, importantly, insertions and back and forth exchange of genetic material between viruses and their hosts. References [1] Di Giovanni, D., Lepetit, D., Boulesteix, M., Ravallec, M., & Varaldi, J. (2018). A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps. bioRxiv, 342758, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/342758 | A behavior-manipulating virus relative as a source of adaptive genes for parasitoid wasps | D. Di Giovanni, D. Lepetit, M. Boulesteix, M. Ravallec, J. Varaldi | <p>To circumvent host immune response, numerous hymenopteran endo-parasitoid species produce virus-like structures in their reproductive apparatus that are injected into the host together with the eggs. These viral-like structures are absolutely n... |  | Adaptation, Behavior & Social Evolution, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution | Ignacio Bravo | 2018-07-18 15:59:14 | View | |

02 Sep 2022

Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough?Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319A match made in the Anthropocene: human-mediated adaptive introgression across a speciation continuumRecommended by Fernando Racimo based on reviews by Michael Westbury, Andrew Foote and Erin CalfeeThe long-distance transport and introduction of new species by humans is increasingly leading divergent lineages to interact, and sometimes interbreed, even after thousands or millions of years of separation. It is thus of prime importance to understand the consequences of these contemporary admixture events on the evolutionary fitness of interacting organisms, and their ecological implications. Ciona robusta and Ciona intestinalis are two species of sea squirts that diverged between 1.5 and 2 million years ago and recently came into contact again. This occurred through human-mediated introduction of C. robusta (native to the Northwest Pacific) into the range of C. intestinalis (the English channeled Northeast Atlantic). In this study, Fraïsse et al. (2022) follow up on earlier work by Le Moan et al. (2021), who had identified a long genomic hotspot of introgression of C. robusta ancestry segments in chromosome 5 of C. intestinalis. The hotspot bears suggestive evidence of positive selection and the authors aimed to investigate this further using fully phased whole-genome sequences. The authors narrow down on the exact boundaries of the introgressed region, and make a compelling case that it has been the likely target of positive selection after introgression, using various complementary approaches based on patterns of population differentiation, haplotype structure and local levels of diversity in the region. Using extensive demographic modeling, they also show that the introgression event was likely recent (approximately 75 years ago), and distinct from other tracts in the C. intestinalis genome that are likely a product of more ancient episodes of interbreeding in the past 30,000 years. Narrowing down on the potential drivers of selection, the authors show that candidate SNPs in the region overlap with the cytochrome family 2 subfamily U gene - involved in the detoxification of exogenous compounds - potentially reflecting adaptation to chemicals encountered in the sea squirt's environment. There also appears to be copy number variation at the candidate SNPs, which provides clues into the adaptation mechanism in the region. All reviewers agreed that the work carried out by the authors is elegant and the results are robustly supported and well presented. In a round of reviews, various clarifications of the manuscript were suggested by the reviewers, including on the quality of the newly generated sequencing data, and some suggestions for qualifications on the conclusions reached by the authors as well as changes in the figures to increase their clarity. The authors addressed the different concerns of the reviewers, and the new version is much improved. This study into human-mediated introgression and its consequences for adaptation is, in my view, both well thought-out and executed. I therefore provide an enthusiastic recommendation of this manuscript. References Fraïsse C, Le Moan A, Roux C, Dubois G, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Gagnaire P-A, Viard F and Bierne N (2022) Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? bioRxiv, 2022.03.22.485319, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.22.485319 Le Moan A, Roby C, Fraïsse C, Daguin-Thiébaut C, Bierne N, Viard F (2021) An introgression breakthrough left by an anthropogenic contact between two ascidians. Molecular Ecology, 30, 6718–6732. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16189 | Introgression between highly divergent sea squirt genomes: an adaptive breakthrough? | Christelle Fraïsse, Alan Le Moan, Camille Roux, Guillaume Dubois, Claire Daguin-Thiébaut, Pierre-Alexandre Gagnaire, Frédérique Viard, Nicolas Bierne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human-mediated introductions are reshuffling species distribution on a global scale. Consequently, an increasing number of allopatric taxa are now brought into contact, promoting introgressive hybridization between ... |  | Adaptation, Hybridization / Introgression, Population Genetics / Genomics | Fernando Racimo | 2022-04-14 15:30:42 | View | |

05 Dec 2017

Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic dataEmeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier https://doi.org/10.1101/139147Predicting small ancestors using contemporary genomes of large mammalsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Bruce Rannala and 1 anonymous reviewerRecent methodological developments and increased genome sequencing efforts have introduced the tantalizing possibility of inferring ancestral phenotypes using DNA from contemporary species. One intriguing application of this idea is to exploit the apparent correlation between substitution rates and body size to infer ancestral species' body sizes using the inferred patterns of substitution rate variation among species lineages based on genomes of extant species [1]. References [1] Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Douzery EJP and Galtier N. 2013. Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 5–13. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss211 [2] Figuet E, Ballenghien M, Lartillot N and Galtier N. 2017. Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 of 4th December 2017. 139147. doi: 10.1101/139147 | Reconstruction of body mass evolution in the Cetartiodactyla and mammals using phylogenomic data | Emeric Figuet, Marion Ballenghien, Nicolas Lartillot, Nicolas Galtier | <p>Reconstructing ancestral characters on a phylogeny is an arduous task because the observed states at the tips of the tree correspond to a single realization of the underlying evolutionary process. Recently, it was proposed that ancestral traits... |  | Genome Evolution, Life History, Macroevolution, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Bruce Rannala | 2017-05-18 15:28:58 | View | |

03 Jun 2019

Transcriptomic response to divergent selection for flowering time in maize reveals convergence and key players of the underlying gene regulatory networkMaud Irène Tenaillon, Khawla Sedikki, Maeva Mollion, Martine Le Guilloux, Elodie Marchadier, Adrienne Ressayre, Christine Dillmann https://doi.org/10.1101/461947Early and late flowering gene expression patterns in maizeRecommended by Tanja Pyhäjärvi based on reviews by Laura Shannon and 2 anonymous reviewersArtificial selection experiments are key experiments in evolutionary biology. The demonstration that application of selective pressure across multiple generations results in heritable phenotypic changes is a tangible and reproducible proof of the evolution by natural selection. References [1] Hill, W. G., & Caballero, A. (1992). Artificial selection experiments. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 23(1), 287-310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.23.110192.001443 | Transcriptomic response to divergent selection for flowering time in maize reveals convergence and key players of the underlying gene regulatory network | Maud Irène Tenaillon, Khawla Sedikki, Maeva Mollion, Martine Le Guilloux, Elodie Marchadier, Adrienne Ressayre, Christine Dillmann | <p>Artificial selection experiments are designed to investigate phenotypic evolution of complex traits and its genetic basis. Here we focused on flowering time, a trait of key importance for plant adaptation and life-cycle shifts. We undertook div... |  | Adaptation, Experimental Evolution, Expression Studies, Quantitative Genetics | Tanja Pyhäjärvi | 2018-11-23 11:57:35 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Guillaume Achaz

Juan Arroyo

Trine Bilde

Dustin Brisson

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

Matteo Fumagalli

Tatiana Giraud

Frédéric Guillaume

Ruth Hufbauer

Sara Magalhaes

Caroline Nieberding

Michael David Pirie

Tanja Pyhäjärvi

Tanja Schwander

Alejandro Gonzalez Voyer