Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 Jul 2022

Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fuscaKamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426Pressing NGS data through the mill of Kmer spectra and allelic coverage ratios in order to scan reproductive modes in non-model speciesRecommended by Nicolas Bierne based on reviews by Paul Simion and 2 anonymous reviewersThe genomic revolution has given us access to inexpensive genetic data for any species. Simultaneously we have lost the ability to easily identify chimerism in samples or some unusual deviations from standard Mendelian genetics. Methods have been developed to identify sex chromosomes, characterise the ploidy, or understand the exact form of parthenogenesis from genomic data. However, we rarely consider that the tissues we extract DNA from could be a mixture of cells with different genotypes or karyotypes. This can nonetheless happen for a variety of (fascinating) reasons such as somatic chromosome elimination, transmissible cancer, or parental genome elimination. Without a dedicated analysis, it is very easy to miss it. In this preprint, Jaron et al. (2022) used an ingenious analysis of whole individual NGS data to test the hypothesis of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. The authors suspected that a high fraction of the whole body of males is made of sperm in this species and if this species undergoes paternal genome elimination, we would expect that sperm would only contain maternally inherited chromosomes. Given the reference genome was highly fragmented, they developed a two-tissue model to analyse Kmer spectra and obtained confirmation that around one-third of the tissue was sperm in males. This allowed them to test whether coverage patterns were consistent with the species exhibiting paternal genome elimination. They combined their estimation of the fraction of haploid tissue with allele coverages in autosomes and the X chromosome to obtain support for a bias toward one parental allele, suggesting that all sperm carries the same parental haplotype. It could be the maternal or the paternal alleles, but paternal genome elimination is most compatible with the known biology of Arthropods. SNP calling was used to confirm conclusions based on the analysis of the raw pileups. I found this study to be a good example of how a clever analysis of Kmer spectra and allele coverages can provide information about unusual modes of reproduction in a species, even though it does not have a well-assembled genome yet. As advocated by the authors, routine inspection of Kmer spectra and allelic read-count distributions should be included in the best practice of NGS data analysis. They provide the method to identify paternal genome elimination but also the way to develop similar methods to detect another kind of genetic chimerism in the avalanche of sequence data produced nowadays. References Jaron KS, Hodson CN, Ellers J, Baird SJ, Ross L (2022) Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca. bioRxiv, 2021.11.12.468426, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.12.468426 | Genomic evidence of paternal genome elimination in the globular springtail Allacma fusca | Kamil S. Jaron, Christina N. Hodson, Jacintha Ellers, Stuart JE Baird, Laura Ross | <p style="text-align: justify;">Paternal genome elimination (PGE) - a type of reproduction in which males inherit but fail to pass on their father’s genome - evolved independently in six to eight arthropod clades. Thousands of species, including s... | Genome Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Nicolas Bierne | 2021-11-18 00:09:43 | View | ||

17 Jun 2022

Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process?Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356The potential evolutionary importance of low-frequency flexibility in reproductive modesRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Michael Lattorff and Jens BastOccasional events of asexual reproduction in otherwise sexual taxa have been documented since a long time. Accounts range from observations of offspring development from unfertilized eggs in Drosophila to rare offspring production by isolated females in lizards and birds (e.g., Stalker 1954, Watts et al 2006, Ryder et al. 2021). Many more such cases likely await documentation, as rare events are inherently difficult to observe. These rare events of asexual reproduction are often associated with low offspring fitness (“tychoparthenogenesis”), and have mostly been discarded in the evolutionary literature as reproductive accidents without evolutionary significance. Recently, however, there has been an increased interest in the details of evolutionary transitions from sexual to asexual reproduction (e.g., Archetti 2010, Neiman et al.2014, Lenormand et al. 2016), because these details may be key to understanding why successful transitions are rare, why they occur more frequently in some groups than in others, and why certain genetic mechanisms of ploidy maintenance or ploidy restoration are more often observed than others. In this context, the hypothesis has been formulated that regular or even obligate asexual reproduction may evolve from these rare events of asexual reproduction (e.g., Schwander et al. 2010). A new study by Capdevielle Dulac et al. (2022) now investigates this question in a parasitoid wasp, highlighting also the fact that what is considered rare or occasional may differ from one system to the next. The results show “rare” parthenogenetic production of diploid daughters occurring at variable frequencies (from zero to 2 %) in different laboratory strains, as well as in a natural population. They also demonstrate parthenogenetic production of female offspring in both virgin females and mated ones, as well as no reduced fecundity of parthenogenetically produced offspring. These findings suggest that parthenogenetic production of daughters, while still being rare, may be a more regular and less deleterious reproductive feature in this species than in other cases of occasional asexuality. Indeed, haplodiploid organisms, such as this parasitoid wasp have been hypothesized to facilitate evolutionary transitions to asexuality (Neimann et al. 2014, Van Der Kooi et al. 2017). First, in haploidiploid organisms, females are diploid and develop from normal, fertilized eggs, but males are haploid as they develop parthenogenetically from unfertilized eggs. This means that, in these species, fertilization is not necessarily needed to trigger development, thus removing one of the constraints for transitions to obligate asexuality (Engelstädter 2008, Vorburger 2014). Second, spermatogenesis in males occurs by a modified meiosis that skips the first meiotic division (e.g., Ferree et al. 2019). Haploidiploid organisms may thus have a potential route for an evolutionary transition to obligate parthenogenesis that is not available to organisms: The pathways for the modified meiosis may be re-used for oogenesis, which might result in unreduced, diploid eggs. Third, the particular species studied here regularly undergoes inbreeding by brother-sister mating within their hosts. Homozygosity, including at the sex determination locus (Engelstädter 2008), is therefore expected to have less negative effects in this species compared to many other, non-inbreeding haplodipoids (see also Little et al. 2017). This particular species may therefore be less affected by loss of heterozygosity, which occurs in a fashion similar to self-fertilization under many forms of non-clonal parthenogenesis. Indeed, the study also addresses the mechanisms underlying parthenogenesis in the species. Surprisingly, the authors find that parthenogenetically produced females are likely produced by two distinct genetic mechanisms. The first results in clonality (maintenance of the maternal genotype), whereas the second one results in a loss of heterozygosity towards the telomeres, likely due to crossovers occurring between the centromeres and the telomeres. Moreover, bacterial infections appear to affect the propensity of parthenogenesis but are unlikely the primary cause. Together, the finding suggests that parthenogenesis is a variable trait in the species, both in terms of frequency and mechanisms. It is not entirely clear to what degree this variation is heritable, but if it is, then these results constitute evidence for low-frequency existence of variable and heritable parthenogenesis phenotypes, that is, the raw material from which evolutionary transitions to more regular forms of parthenogenesis may occur.

References Archetti M (2010) Complementation, Genetic Conflict, and the Evolution of Sex and Recombination. Journal of Heredity, 101, S21–S33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esq009 Capdevielle Dulac C, Benoist R, Paquet S, Calatayud P-A, Obonyo J, Kaiser L, Mougel F (2022) Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? bioRxiv, 2021.12.13.472356, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.13.472356 Engelstädter J (2008) Constraints on the evolution of asexual reproduction. BioEssays, 30, 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20833 Ferree PM, Aldrich JC, Jing XA, Norwood CT, Van Schaick MR, Cheema MS, Ausió J, Gowen BE (2019) Spermatogenesis in haploid males of the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Scientific Reports, 9, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48332-9 van der Kooi CJ, Matthey-Doret C, Schwander T (2017) Evolution and comparative ecology of parthenogenesis in haplodiploid arthropods. Evolution Letters, 1, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.30 Lenormand T, Engelstädter J, Johnston SE, Wijnker E, Haag CR (2016) Evolutionary mysteries in meiosis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20160001. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0001 Little CJ, Chapuis M-P, Blondin L, Chapuis E, Jourdan-Pineau H (2017) Exploring the relationship between tychoparthenogenesis and inbreeding depression in the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3103 Neiman M, Sharbel TF, Schwander T (2014) Genetic causes of transitions from sexual reproduction to asexuality in plants and animals. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 1346–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12357 Ryder OA, Thomas S, Judson JM, Romanov MN, Dandekar S, Papp JC, Sidak-Loftis LC, Walker K, Stalis IH, Mace M, Steiner CC, Chemnick LG (2021) Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors. Journal of Heredity, 112, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esab052 Schwander T, Vuilleumier S, Dubman J, Crespi BJ (2010) Positive feedback in the transition from sexual reproduction to parthenogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.2113 Stalker HD (1954) Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics, 39, 4–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/39.1.4 Vorburger C (2014) Thelytoky and Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera: Mutual Constraints. Sexual Development, 8, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356508 Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (2006) Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. Nature, 444, 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/4441021a | Spontaneous parthenogenesis in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia typhae: low frequency anomaly or evolving process? | Claire Capdevielle Dulac, Romain Benoist, Sarah Paquet, Paul-André Calatayud, Julius Obonyo, Laure Kaiser, Florence Mougel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Hymenopterans are haplodiploids and unlike most other Arthropods they do not possess sexual chromosomes. Sex determination typically happens via the ploidy of individuals: haploids become males and diploids become f... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2021-12-16 15:25:16 | View | |

16 Jun 2022

Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic beeRebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030Taking advantage of facultative sociality in sweat bees to study the developmental plasticity of antennal sense organs and its association with social phenotypeRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield, Sylvia Anton and Lluís Socias-MartínezThe study of the evolution of sociality is closely associated with the study of the evolution of sensory systems. Indeed, group life and sociality necessitate that individuals recognize each other and detect outsiders, as seen in eusocial insects such as Hymenoptera. While we know that antennal sense organs that are involved in olfactory perception are found in greater densities in social species of that group compared to solitary hymenopterans, whether this among-species correlation represents the consequence of social evolution leading to sensory evolution, or the opposite, is still questioned. Knowing more about how sociality and sensory abilities covary within a species would help us understand the evolutionary sequence. Studying a species that shows social plasticity, that is facultatively social, would further allow disentangling the cause and consequence of social evolution and sensory systems and the implication of plasticity in the process. Boulton and Field (2022) studied a species of sweat bee that shows social plasticity, Halictus rubicundus. They studied populations at different latitudes in Great Britain: populations in the North are solitary, while populations in the south often show sociality, as they face a longer and warmer growing season, leading to the opportunity for two generations in a single year, a pre-condition for the presence of workers provisioning for the (second) brood. Using scanning electron microscope imaging, the authors compared the density of antennal sensilla types in these different populations (north, mid-latitude, south) to test for an association between sociality and olfactory perception capacities. They counted three distinct types of antennal sensilla: olfactory plates, olfactory hairs, and thermos/hygro-receptive pores, used to detect humidity, temperature and CO2. In addition, they took advantage of facultative sociality in this species by transplanting individuals from a northern population (solitary) to a southern location (where conditions favour sociality), to study how social plasticity is reflected (or not) in the density of antennal sensilla types. They tested the prediction that olfactory sensilla density is also developmentally plastic in this species. Their results show that antennal sensilla counts differ between the 3 studied regions (north, mid-latitude, south), but not as predicted. Individuals in the southern population were not significantly different from the mid-latitude and northern ones in their count of olfactory plates and they had less, not more, thermos/hygro receptors than mid-latitude and northern individuals. Furthermore, mid-latitude individuals had more olfactory hairs than the ones from the northern population and did not differ from southern ones. The prediction was that the individuals expressing sociality would have the highest count of these olfactory hairs. This unpredicted pattern based on the latitude of sampling sites may be due to the effect of temperature during development, which was higher in the mid-latitude site than in the southern one. It could also be the result of a genotype-by-environment interaction, where the mid-latitude population has a different developmental response to temperature compared to the other populations, a difference that is genetically determined (a different “reaction norm”). Reciprocal transplant experiments coupled with temperature measurements directly on site would provide interesting information to help further dissect this intriguing pattern. Interestingly, where a sweat bee developed had a significant effect on their antennal sensilla counts: individuals originating from the North that developed in the south after transplantation had significantly more olfactory hairs on their antenna than individuals from the same Northern population that developed in the North. This is in accordance with the prediction that the characteristics of sensory organs can also be plastic. However, there was no difference in antennal characteristics depending on whether these transplanted bees became solitary or expressed the social phenotype (foundress or worker). This result further supports the hypothesis that temperature affects development in this species and that these sensory characteristics are also plastic, although independently of sociality. Overall, the work of Boulton and Field underscores the importance of including phenotypic plasticity in the study of the evolution of social behaviour and provides a robust and fruitful model system to explore this further. References Boulton RA, Field J (2022) Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. bioRxiv, 2022.01.29.478030, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.29.478030 | Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee | Rebecca A Boulton, Jeremy Field | <p style="text-align: justify;">The social Hymenoptera have contributed much to our understanding of the evolution of sensory systems. Attention has focussed chiefly on how sociality and sensory systems have evolved together. In the Hymenoptera, t... |  | Behavior & Social Evolution, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2022-02-02 11:34:49 | View | |

31 Mar 2022

Gene network robustness as a multivariate characterArnaud Le Rouzic https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2101.01564Genetic and environmental robustness are distinct yet correlated evolvable traits in a gene networkRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert based on reviews by Diogo Melo, Charles Mullon and Charles Rocabert

Organisms often show robustness to genetic or environmental perturbations. Whether these two components of robustness can evolve separately is the focus of the paper by Le Rouzic [1]. Using theoretical analysis and individual-based computer simulations of a gene regulatory network model, he shows that multiple aspects of robustness can be investigated as a set of pleiotropically linked quantitative traits. While genetically correlated, various robustness components (e.g., mutational, developmental, homeostasis) of gene expression in the regulatory network evolved more or less independently from each other under directional selection. The quantitative approach of Le Rouzic could explain both how unselected robustness components can respond to selection on other components and why various robustness-related features seem to have their own evolutionary history. Moreover, he shows that all components were evolvable, but not all to the same extent. Robustness to environmental disturbances and gene expression stability showed the largest responses while increased robustness to genetic disturbances was slower. Interestingly, all components were positively correlated and remained so after selection for increased or decreased robustness. This study is an important contribution to the discussion of the evolution of robustness in biological systems. While it has long been recognized that organisms possess the ability to buffer genetic and environmental perturbations to maintain homeostasis (e.g., canalization [2]), the genetic basis and evolutionary routes to robustness and canalization are still not well understood. Models of regulatory gene networks have often been used to address aspects of robustness evolution (e.g., [3]). Le Rouzic [1] used a gene regulatory network model derived from Wagner’s model [4]. The model has as end product the expression level of a set of genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors). The level and stability of expression are a property of the regulatory interactions in the network. Le Rouzic made an important contribution to the study of such gene regulation models by using a quantitative genetics approach to the evolution of robustness. He crafted a way to assess the mutational variability and selection response of the components of robustness he was interested in. Le Rouzic’s approach opens avenues to investigate further aspects of gene network evolutionary properties, for instance to understand the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Le Rouzic also discusses ways to measure his different robustness components in empirical studies. As the model is about gene expression levels at a set of protein-coding genes influenced by a set of regulatory elements, it naturally points to the possibility of using RNA sequencing to measure the variation of gene expression in know gene networks and assess their robustness. Robustness could then be studied as a multidimensional quantitative trait in an experimental setting. References [1] Le Rouzic, A (2022) Gene network robustness as a multivariate character. arXiv: 2101.01564, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.01564 [2] Waddington CH (1942) Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/150563a0 [3] Draghi J, Whitlock M (2015) Robustness to noise in gene expression evolves despite epistatic constraints in a model of gene networks. Evolution, 69, 2345–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12732 [4] Wagner A (1994) Evolution of gene networks by gene duplications: a mathematical model and its implications on genome organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 4387–4391. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.10.4387 | Gene network robustness as a multivariate character | Arnaud Le Rouzic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Robustness to genetic or environmental disturbances is often considered as a key property of living systems. Yet, in spite of being discussed since the 1950s, how robustness emerges from the complexity of genetic ar... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Theory, Genotype-Phenotype, Quantitative Genetics | Frédéric Guillaume | Charles Mullon, Charles Rocabert, Diogo Melo | 2021-01-11 17:48:20 | View |

22 Mar 2022

Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus CorbiculaVastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836Strange reproductive modes and population geneticsRecommended by Chris Jiggins based on reviews by Arnaud Estoup, Simon Henry Martin and 2 anonymous reviewersThere are many organisms that are asexual or have unusual modes of reproduction. One such quasi-sexual reproductive mode is androgenesis, in which the offspring, after fertilization, inherits only the entire paternal nuclear genome. The maternal genome is ditched along the way. One group of organisms which shows this mode of reproduction are clams in the genus Corbicula, some of which are androecious, while others are dioecious and sexual. The study by Vastrade et al. (2022) describes population genetic patterns in these clams, using both nuclear and mitochondrial sequence markers. In contrast to what might be expected for an asexual lineage, there is evidence for significant genetic mixing between populations. In addition, there is high heterozygosity and evidence for polyploidy in some lineages. Overall, the picture is complicated! However, what is clear is that there is far more genetic mixing than expected. One possible mechanism by which this could occur is 'nuclear capture' where there is a mixing of maternal and paternal lineages after fertilization. This can sometimes occur as a result of hybridization between 'species', leading to further mixing of divergent lineages. Thus the group is clearly far from an ancient asexual lineage - recombination and mixing occur with some regularity. The study also analyzed recent invasive populations in Europe and America. These had reduced genetic diversity, but also showed complex patterns of allele sharing suggesting a complex origin of the invasive lineages. In the future, it will be exciting to apply whole genome sequencing approaches to systems such as this. There are challenges in interpreting a handful of sequenced markers especially in a system with polyploidy and considerable complexity, and whole-genome sequencing could clarify some of the outstanding questions, Overall, this paper highlights the complex genetic patterns that can result through unusual reproductive modes, which provides a challenge for the field of population genetics and for the recognition of species boundaries. References Vastrade M, Etoundi E, Bournonville T, Colinet M, Debortoli N, Hedtke SM, Nicolas E, Pigneur L-M, Virgo J, Flot J-F, Marescaux J, Doninck KV (2022) Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. bioRxiv, 590836, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/590836 | Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula | Vastrade M., Etoundi E., Bournonville T., Colinet M., Debortoli N., Hedtke S.M., Nicolas E., Pigneur L.-M., Virgo J., Flot J.-F., Marescaux J. and Van Doninck K. | <p style="text-align: justify;">“Occasional” sexuality occurs when a species combines clonal reproduction and genetic mixing. This strategy is predicted to combine the advantages of both asexuality and sexuality, but its actual consequences on the... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Hybridization / Introgression, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Chris Jiggins | 2019-03-29 15:42:56 | View | |

12 Nov 2021

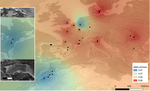

How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy treeJordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.25.394544An ancient age of open-canopy landscapes in northern Madagascar? Evidence from the population genetic structure of a forest treeRecommended by Miguel de Navascués based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona based on reviews by Katharina Budde and Yurena Arjona

We currently live in the Anthropocene, the geological age characterized by a profound impact of human populations in the ecosystems and the environment. While there is little doubt about the action of humans in the shaping of present landscapes, it can be difficult to determine what the state of those landscapes was before humans started to modify them. This is the case of the Madagascar grasslands, whose origins have been debated with arguments proposing them either as anthropogenic, created with the arrival of humans around 2000BP, or as ancient features of the natural landscape with a forest fragmentation process due to environmental changes pre-dating human arrival [e.g. 1,2]. One way to clarify this question is through the genetic study of native species. Population continuity and fragmentation along time shape the structure of the genetic diversity in space. Species living in a uniform continuous habitat are expected to show genetic structuring determined only by geographical distance. Recent changes of the habitat can take many generations to reshape that genetic structure [3]. Thus, we expect genetic structure to reflect ancient features of the landscape. The work by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] studies the factors determining the population genetic structure of the Malagasy spiny olive (Noronhia spinifolia). This narrow endemic species is distributed in the discontinuous forest patches of the Loky-Manambato region (northern Madagascar). Jordi Salmona and collaborators genotyped 72 individuals distributed across the species distribution with restriction associated DNA sequencing and organelle microsatellite markers. Then, they studied the population genetic structure of the species. Using isolation-by-resistance models [5], they tested the influence of several landscape features (forest cover, roads, rivers, slope, etc.) on the connectivity between populations. Maternally inherited loci (chloroplast and mitochondria) and bi-parentally inherited loci (nuclear), were analysed separately in an attempt to identify the role of pollen and seed dispersal in the connectivity of populations. Despite the small distribution of the species, Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] found remarkable levels of genetic diversity. The spatial structure of this diversity was found to be mainly explained by the forest cover of the landscape, suggesting that the landscape has been composed by patches of forests and grasslands for a long time. The main role of forest cover for the connectivity among populations also highlights the importance of riparian forest as dispersal corridors. Finally, differences between organelle and nuclear markers were not enough to establish any strong conclusion about the differences between pollen and seed dispersal. The results presented by Jordi Salmona and collaborators [4] contribute to the understanding of the history and ecology of understudied Madagascar ecosystems. Previous population genetic studies in some forest-dwelling mammals have been interpreted as supporting an old age for the fragmented landscapes in northern Madagascar [e.g. 1,6]. To my knowledge, this is the first study on a tree species. While this work might not completely settle the debate, it emphasizes the importance of studying a diversity of species to understand the biogeographic dynamics of a region. References 1. Quéméré, E., X. Amelot, J. Pierson, B. Crouau-Roy, L. Chikhi (2012) Genetic data suggest a natural prehuman origin of open habitats in northern Madagascar and question the deforestation narrative in this region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of | How ancient forest fragmentation and riparian connectivity generate high levels of genetic diversity in a micro-endemic Malagasy tree | Jordi Salmona, Axel Dresen, Anicet E. Ranaivoson, Sophie Manzi, Barbara Le Pors, Cynthia Hong-Wa, Jacqueline Razanatsoa, Nicole V. Andriaholinirina, Solofonirina Rasoloharijaona, Marie-Elodie Vavitsara, Guillaume Besnard | <p>Understanding landscape changes is central to predicting evolutionary trajectories and defining conservation practices. While human-driven deforestation is intense throughout Madagascar, exception in areas like the Loky-Manambato region (North)... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Miguel de Navascués | 2020-11-27 09:07:21 | View | |

08 Nov 2021

Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicumJelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895Sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect: pattern during development, extent, functions involved, rate of sequence evolution, and comparison with an holometabolous insectRecommended by Nadia Aubin-Horth based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAn individual’s sexual phenotype is determined during development. Understanding which pathways are activated or repressed during the developmental stages leading to a sexually mature individual, for example by studying gene expression and how its level is biased between sexes, allows us to understand the functional aspects of dimorphic phenotypes between the sexes. Several studies have quantified the differences in transcription between the sexes in mature individuals, showing the extent of this sex-bias and which functions are affected. There is, however, less data available on what occurs during the different phases of development leading to this phenotype, especially in species with specific developmental strategies, such as hemimetabolous insects. While many well-studied insects such as the honey bee, drosophila, and butterflies, exhibit an holometabolous development ("holo" meaning "complete" in reference to their drastic metamorphosis from the juvenile to the adult stage), hemimetabolous insects have juvenile stages that look similar to the adult stage (the hemi prefix meaning "half", referring to the more tissue-specific changes during development), as seen in crickets, cockroaches, and stick insects. Learning more about what happens during development in terms of the identity of genes that are sex-biased (are they the same genes at different developmental stages? What are their function? Do they exhibit specific sequence evolution rates? Is one sex over-represented in the sex-biased genes?) and their quantity over developmental time (gradual or abrupt increase in number, if any?) would allow us to better understand the evolution of sexual dimorphism at the gene expression level and how it relates to dimorphism at the organismic level. Djordjevic et al (2021) studied the transcriptome during development in an hemimetabolous stick insect, to improve our knowledge of this type of development, where the organismic phenotype is already mostly present in the early life stages. To do this, they quantified whole-genome gene expression levels in whole insects, using RNA-seq at three different developmental stages. One of the interesting results presented by Djordjevic and colleagues is that the increase in the number of genes that were sex-biased in expression is gradual over the three stages of development studied and it is mostly the same genes that stay sex-biased over time, reflecting the gradual change in phenotypes between hatchlings, juveniles and adults. Furthermore, male-biased genes had faster sequence divergence rates than unbiased genes and that female-biased genes. This new information of sex-bias in gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect allowed the authors to do a comparison of sex-biased genes with what has been found in a well-studied holometabolous insect, Drosophila. The gene expression patterns showed that four times more genes were sex-biased in expression in that species than in stick insects. Furthermore, the increase in the number of sex-biased genes during development was quite abrupt and clearly distinct in the adult stage, a pattern that was not seen in stick insects. As pointed out by the authors, this pattern of a "burst" of sex-biased genes at maturity is more common than the gradual increase seen in stick insects. With this study, we now know more about the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in an hemimetabolous insect and how it relates to their phenotypic dimorphism. Clearly, the next step will be to sample more hemimetabolous species at different life stages, to see how this pattern is widespread or not in this mode of development in insects. References Djordjevic J, Dumas Z, Robinson-Rechavi M, Schwander T, Parker DJ (2021) Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression during development in the stick insect Timema californicum. bioRxiv, 2021.01.23.427895, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.23.427895 | Dynamics of sex-biased gene expression over development in the stick insect Timema californicum | Jelisaveta Djordjevic, Zoé Dumas, Marc Robinson-Rechavi, Tanja Schwander, Darren James Parker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Sexually dimorphic phenotypes are thought to arise primarily from sex-biased gene expression during development. Major changes in developmental strategies, such as the shift from hemimetabolous to holometabolous dev... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Nadia Aubin-Horth | 2021-04-22 17:36:32 | View | |

26 Oct 2021

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewer

Each individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

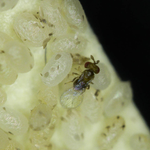

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang