More intense symptoms, more treatment, more drug-resistance: coevolution of virulence and drug-resistance

Recommended by Ludek Berec based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

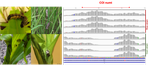

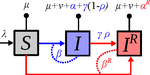

Mathematical models play an essential role in current evolutionary biology, and evolutionary epidemiology is not an exception [1]. While the issues of virulence evolution and drug-resistance evolution resonate in the literature for quite some time [2, 3], the study by Alizon [4] is one of a few that consider co-evolution of both these traits [5]. The idea behind this study is the following: treating individuals with more severe symptoms at a higher rate (which appears to be quite natural) leads to an appearance of virulent drug-resistant strains, via treatment failure. The author then shows that virulence in drug-resistant strains may face different selective pressures than in drug-sensitive strains and hence proceed at different rates. Hence, treatment itself modulates evolution of virulence. As one of the reviewers emphasizes, the present manuscript offers a mathematical view on why the resistant and more virulent strains can be selected in epidemics. Also, we both find important that the author highlights that the topic and results of this study can be attributed to public health policies and development of optimal treatment protocols [6].

Mathematical models are simplified representations of reality, created with a particular purpose. It can be simple as well as complex, but even simple models can produce relatively complex and knitted results. The art of modelling thus lies not only in developing a model, but also in interpreting and unknitting the results. And this is what Alizon [4] indeed does carefully and exhaustively. Using two contrasting theoretical approaches to study co-evolution, the Price equation approach to study short-term evolution and the adaptive dynamics approach to study long-term evolution, Alizon [4] shows that a positive correlation between the rate of treatment and infection severity causes virulence in drug-sensitive strains to decrease. Clearly, no single model can describe and explain an examined system in its entirety, and even this aspect of the work is taken seriously. Many possible extensions of the study are laid out, providing a wide opportunity to pursue this topic even further. Personally, I have had an opportunity to read many Alizon’s papers and use, teach or discuss many of his models and results. All, including the current one, keep high standard and pursue the field of theoretical (evolutionary) epidemiology.

References

[1] Gandon S, Day T, Metcalf JE, Grenfell BT (2016) Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends Ecol Evol 31: 776-788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010

[2] Berngruber TW, Froissart R, Choisy M, Gandon S (2013) Evolution of virulence in emerging epidemics. PLoS Pathog 9(3): e1003209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003209

[3] Spicknall IH, Foxman B, Marrs CF, Eisenberg JNS (2013) A modeling framework for the evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance: literature review and model categorization. Am J Epidemiol 178: 508-520. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt017

[4] Alizon S (2020) Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistance. bioRxiv, 2020.02.29.970905, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.970905

[5] Carval D, Ferriere R (2010) A unified model for the coevolution of resistance, tolerance, and virulence. Evolution 64: 2988–3009. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01035.x

[6] Read AF, T Day, and S Huijben (2011). The evolution of drug resistance and the curious orthodoxy of aggressive chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 Suppl 2, 10871–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100299108

| Treating symptomatic infections and the co-evolution of virulence and drug resistance | Samuel Alizon | <p>Antimicrobial therapeutic treatments are by definition applied after the onset of symptoms, which tend to correlate with infection severity. Using mathematical epidemiology models, I explore how this link affects the coevolutionary dynamics bet... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Ludek Berec | | 2020-03-04 10:18:39 | View |

Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis

David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265

Temperature effects on virulence evolution of wMelPop Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogaster

Recommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Shira Houwenhuyse and 3 anonymous reviewers

Monnin et al. [1] here studied how Drosophila populations are affected when exposed to a high virulent endosymbiotic wMelPop Wolbachia strain and why virulent vertically transmitting endosymbionts persist in nature. This virulent wMelPop strain has been described to be a blocker of dengue and other arboviral infections in arthropod vector species, such as Aedes aegypti. Whereas it can thus function as a mutualistic symbiont, it here acts as an antagonist along the mutualism-antagonism continuum symbionts operate. The wMelPop strain is not a natural occurring strain in Drosophila melanogaster and thus the start of this experiment can be seen as a novel host-pathogen association. Through experimental evolution of 17 generations, the authors studied how high temperature affects wMelPop Wolbachia virulence and Drosophila melanogaster survival. The authors used Drosophila strains that were selected for late reproduction, given that this should favor evolution to a lower virulence. Assumptions for this hypothesis are not given in the manuscript here, but it can indeed be assumed that energy that is assimilated to symbiont tolerance instead of reproduction may lead to reduced virulence evolution. This has equally been suggested by Reyserhove et al. [2] in a dynamics energy budget model tailored to Daphnia magna virulence evolution upon a viral infection causing White fat Cell disease, reconstructing changing environments through time.

Contrary to their expectations for vertically transmitting symbionts, the authors did not find a reduction in wMelPop Wolbachia virulence during the course of the experimental evolution experiment under high temperature. Important is what this learns for virulence evolution, also for currently horizontal transmitting disease epidemics (such as COVID-19). It mainly reflects that evolution of virulence for new host-pathogen associations is difficult to predict and that it may take multiple generations before optimal levels of virulence are reached [3,4]. These optimal levels of virulence will depend on trade-offs with other life history traits of the symbiont, but also on host demography, host heterogeneity, amongst others [5,6]. Multiple microbial interactions may affect the outcome of virulence evolution [7]. Given that no germ-free individuals were used, it can be expected that other components of the Drosophila microbiome may have played a role in the virulence evolution. In most cases, microbiota have been described as defensive or protective for virulent symbionts [8], but they may also have stimulated the high levels of virulence. Especially, given that upon higher temperatures, Wolbachia growth may have been increased, host metabolic demands increased [9], host immune responses affected and microbial communities changed [10]. This may have resulted in increased competitive interactions to retrieve host resources, sustaining high virulence levels of the symbiont.

A nice asset of this study is that the phenotypic results obtained in the experimental evolution set-up were linked with wMelPop density measurement and octomom copy number quantifications. Octomom is a specific 8-n genes region of the Wolbachia genome responsible for wMelPop virulence, so there is a link between the phenotypic and molecular functions of the involved symbiont. The authors found that density, octomom copy number and virulence were correlated to each other. An important note the authors address in their discussion is that, to exclude the possibility that octomom copy number has an effect on density, and density on virulence, the effect of these variables should be assessed independently of temperature and age. The obtained results are a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate on the relationship between wMelPop octomom copy number, density and virulence.

References

[1] Monnin, D., Kremer, N., Michaud, C., Villa, M., Henri, H., Desouhant, E. and Vavre, F. (2020) Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis. bioRxiv, 2020.04.26.062265, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.26.062265

[2] Reyserhove, L., Samaey, G., Muylaert, K., Coppé, V., Van Colen, W., and Decaestecker, E. (2017). A historical perspective of nutrient change impact on an infectious disease in Daphnia. Ecology, 98(11), 2784-2798. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1994

[3] Ebert, D., and Bull, J. J. (2003). Challenging the trade-off model for the evolution of virulence: is virulence management feasible?. Trends in microbiology, 11(1), 15-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00003-3

[4] Houwenhuyse, S., Macke, E., Reyserhove, L., Bulteel, L., and Decaestecker, E. (2018). Back to the future in a petri dish: Origin and impact of resurrected microbes in natural populations. Evolutionary Applications, 11(1), 29-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12538

[5] Day, T., and Gandon, S. (2007). Applying population‐genetic models in theoretical evolutionary epidemiology. Ecology Letters, 10(10), 876-888. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01091.x

[6] Alizon, S., Hurford, A., Mideo, N., and Van Baalen, M. (2009). Virulence evolution and the trade‐off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of evolutionary biology, 22(2), 245-259. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x

[7] Alizon, S., de Roode, J. C., and Michalakis, Y. (2013). Multiple infections and the evolution of virulence. Ecology letters, 16(4), 556-567. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12076

[8] Decaestecker, E., and King, K. (2019). Red queen dynamics. Reference module in earth systems and environmental sciences, 3, 185-192. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10550-0

[9] Kirk, D., Jones, N., Peacock, S., Phillips, J., Molnár, P. K., Krkošek, M., and Luijckx, P. (2018). Empirical evidence that metabolic theory describes the temperature dependency of within-host parasite dynamics. PLoS biology, 16(2), e2004608. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004608

[10] Frankel-Bricker, J., Song, M. J., Benner, M. J., and Schaack, S. (2019). Variation in the microbiota associated with Daphnia magna across genotypes, populations, and temperature. Microbial ecology, 1-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-019-01412-9

| Experimental evolution of virulence and associated traits in a Drosophila melanogaster – Wolbachia symbiosis | David Monnin, Natacha Kremer, Caroline Michaud, Manon Villa, Hélène Henri, Emmanuel Desouhant, Fabrice Vavre | <p>Evolutionary theory predicts that vertically transmitted symbionts are selected for low virulence, as their fitness is directly correlated to that of their host. In contrast with this prediction, the Wolbachia strain wMelPop drastically reduces... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Ellen Decaestecker | | 2020-04-29 19:16:56 | View |

Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population

Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

Detecting loci under natural selection from temporal genomic data of selfing populations

Recommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

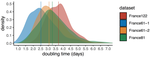

The observed levels of genomic diversity in contemporary populations are the result of changes imposed by several evolutionary processes. Among them, natural selection is known to dramatically shape the genetic diversity of loci associated with phenotypes which affect the fitness of carriers. As such, many efforts have been dedicated towards developing methods to detect signatures of natural selection from genomes of contemporary samples [1].

Recent technological advances made the generation of large-scale genomic data from temporal samples, either from experimental populations or historical or ancient samples, accessible to a wide scientific community [2]. Notably, temporal population genomic data allow for a direct observation and study of how, for instance, allele frequencies change through time in response to evolutionary stimuli. Such information can be exploited to detect loci under natural selection, either via mathematical modelling or by investigating empirical distributions [3].

However, most of current methods to detect selection from temporal genomic data have largely ignored selfing populations, despite the latter comprising a significant proportion of species with social and economic importance. Selfing changes genomic patterns by reducing the effective recombination rate, which makes distinguishing between neutral evolution and natural selection even more challenging than for the case of outcrossing populations [4]. Nevertheless, an outlier-approach based on temporal genomic data for the selfing Arabidopsis thaliana population revealed loci under selection [5].

This study suggested the promise of detecting selection for selfing populations and encouraged further investigations to test the power of selection scans under different mating systems.

To address this question, Navascués et al. [6] extended a previously proposed approach for temporal genome scan [7] to incorporate partial self-fertilization. In the original implementation [7], it is assumed that, under neutrality, all loci provide levels of genetic differentiation drawn from the same distribution. If some of the loci are under selection, such distribution should show heterogeneity. Navascués et al. [6] proposed a test for the homogeneity between loci-specific and genome-wide differentiation by deriving a null distribution of FST via simulations using SLiM [8]. After filtering for low-frequency variants and correct for multiple tests, authors derived a statistical test for selection and assess its power under a wide range of scenarios of selfing rate, selection coefficient, duration and type of selection [6].

The newly proposed test achieved good performance to distinguish between neutral and selected loci in most tested scenarios.

As expected, the test's performance significantly drops for scenarios of high selfing rates and selection from standing variation. Additionally, the probability to correctly detect selection decreases with increasing distance from the causal variant. Intriguingly, the test showed high power when the selected ancestral allele had an initial low frequency, and when the selected derived allele had a high initial frequency. When applied to a data set of around 1,000 SNPs from the highly selfing Medicago truncatula population, an annual plant of the legume family [9], the test did not provide any candidate loci under selection [6].

In summary, the detection of loci under selection in selfing populations is and largely remains a challenging task even when explictly account for the different mating system. However, recombination events that occurred before the selective pressure allow ancestral beneficial alleles to exhibit a detectable pattern of non-neutrality. As such, in partially selfing populations, the strength of the footprint of selection depends on several factors, mostly on the selfing rate, the time of onset and type of selection.

One major assumption of this study is that the model implies unstructured population and continuity between samples obtained from the same geographical location over time. As such assumptions are typically violated in real populations, further research into the effect of more complex demographic scenarios is desired to fully understand the power to detect selection in selfing populations. Furthermore, more power could be gained by including additional genomic information at each time point. In this context, recent approaches that make full use of genomic data based on deep learning [10] may contribute significantly towards this goal. Similarly, the effect of data filtering on the power to detect selection should be further explored, especially in the context of DNA resequencing experiments. These analyses will help elucidate the power offered by selection scans from temporal genomic data in selfing populations.

References

[1] Stern AJ, Nielsen R (2019) Detecting Natural Selection. In: Handbook of Statistical Genomics , pp. 397–40. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119487845.ch14

[2] Leonardi M, Librado P, Der Sarkissian C, Schubert M, Alfarhan AH, Alquraishi SA, Al-Rasheid KAS, Gamba C, Willerslev E, Orlando L (2017) Evolutionary Patterns and Processes: Lessons from Ancient DNA. Systematic Biology, 66, e1–e29. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw059

[3] Dehasque M, Ávila‐Arcos MC, Díez‐del‐Molino D, Fumagalli M, Guschanski K, Lorenzen ED, Malaspinas A-S, Marques‐Bonet T, Martin MD, Murray GGR, Papadopulos AST, Therkildsen NO, Wegmann D, Dalén L, Foote AD (2020) Inference of natural selection from ancient DNA. Evolution Letters, 4, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.165

[4] Vitalis R, Couvet D (2001) Two-locus identity probabilities and identity disequilibrium in a partially selfing subdivided population. Genetics Research, 77, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300004833

[5] Frachon L, Libourel C, Villoutreix R, Carrère S, Glorieux C, Huard-Chauveau C, Navascués M, Gay L, Vitalis R, Baron E, Amsellem L, Bouchez O, Vidal M, Le Corre V, Roby D, Bergelson J, Roux F (2017) Intermediate degrees of synergistic pleiotropy drive adaptive evolution in ecological time. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 1, 1551–1561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0297-1

[6] Navascués M, Becheler A, Gay L, Ronfort J, Loridon K, Vitalis R (2020) Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population. bioRxiv, 2020.05.06.080895, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.080895

[7] Goldringer I, Bataillon T (2004) On the Distribution of Temporal Variations in Allele Frequency: Consequences for the Estimation of Effective Population Size and the Detection of Loci Undergoing Selection. Genetics, 168, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.103.025908

[8] Messer PW (2013) SLiM: Simulating Evolution with Selection and Linkage. Genetics, 194, 1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.113.152181

[9] Siol M, Prosperi JM, Bonnin I, Ronfort J (2008) How multilocus genotypic pattern helps to understand the history of selfing populations: a case study in Medicago truncatula. Heredity, 100, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2008.5

[10] Sanchez T, Cury J, Charpiat G, Jay F Deep learning for population size history inference: Design, comparison and combination with approximate Bayesian computation. Molecular Ecology Resources, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13224

| Power and limits of selection genome scans on temporal data from a selfing population | Miguel Navascués, Arnaud Becheler, Laurène Gay, Joëlle Ronfort, Karine Loridon, Renaud Vitalis | <p>Tracking genetic changes of populations through time allows a more direct study of the evolutionary processes acting on the population than a single contemporary sample. Several statistical methods have been developed to characterize the demogr... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Matteo Fumagalli | | 2020-05-08 10:34:31 | View |

Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantage

Ludovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens

https://doi.org/10.1101/616409

Evolutionary insights into disassortative mating and its association to an ecologically relevant supergene

Recommended by Charles Mullon based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers

*Heliconius* butterflies are famous for their colorful wing patterns acting as a warning of their chemical defenses [1]. Most species are involved in Müllerian mimicry assemblies, as predators learn to associate common wing patterns with unpalatability and preferentially target rare variants. Such positive-frequency dependent selection homogenizes wing patterns at different localities, and in several species, all individuals within a community belong to the same morph [2]. In this respect, *H. numata* stands out. This species shows stable local polymorphism across multiple localities, with local populations home to up to seven distinct morphs [2]. Although a balance between migration and local positive-frequency dependent selection can allow some degree of local polymorphism, theory suggests that this occurs only when migration is within a narrow window [3]. One factor that potentially enhances local polymorphism in *H. numata* is disassortative mating. Mate choice assays have in fact revealed that females of this species tend to reject males with the same wing pattern [4]. However the evolution of such mating behavior and its effect on polymorphism remain unclear when selection is locally positive-frequency dependent. Using a mathematical model, Maisonneuve *et al.* [5] clarify the conditions that favor the evolution of disassortative mating in the complicated system of *H. numata*. In particular, they investigate whether the genetic basis of wing colour can favor the emergence of disassortative mating. Variation in wing pattern in *H. numata* is controlled by the supergene P, which is a single genomic region harboring multiple protein coding genes that have ceased to recombine due to chromosomal inversions [6]. If such remarkable genetic configuration allows for the co-adaptation of multiple loci participating to a complex phenotype such as wing color pattern, the absence of recombination can also result in the accumulation of deleterious mutations [7]. In fact, alleles at the P locus have been associated with a recessive genetic load, leading to a fitness advantage for heterozygotes at this locus [8]. Can this fitness advantage to heterozygotes lead to the evolution of disassortative mating? And if so, can such evolution lead to the maintenance of local polymorphism in spite of strong positive frequency-dependent selection? To investigate these questions, Maisonneuve *et al.* [5] model evolution at two loci, one is the P locus for wing pattern, and the other influences mating behavior. The population is divided among two connected patches that differ in their butterfly communities, so that different alleles at the P locus are favored by positive frequency-dependent selection in different patches. The different alleles at the P locus are ordered in dominance relationships such that the most dominant over wing color pattern are also those with the highest load. By tracking the dynamics of haplotype frequencies in the population, the authors first show that disassortative mating readily evolves via the invasion of an allele causing females carrying it to reject males that resemble them phenotypically. Such “self-referencing” mechanism of mate choice, however, has never been reported and has been argued to be rare due to its complicated nature [9]. Maisonneuve *et al.* [5] then compare the evolution of disassortative mating via two alternative mechanisms: attraction and rejection. In these cases, alleles at the mating locus determine attraction to or rejection of specific phenotypes (e.g., under attraction rule, allele “B” encodes attraction to males with phenotype B). With the P and mating loci fully linked, disassortative mating can evolve under all three mechanisms (self-referencing, attraction and rejection), but tends to be less prevalent at equilibrium under attraction rule. This in turn results in the maintenance of less genetic variation under attraction compared to the other mating mechanisms. The loss of variation that occurs under attraction rules is due to a combination of dominance relationships between alleles at the P locus and the searching cost to females in finding rare types of males. When a particular wing pattern, say B, is only expressed in homozygotic form, B males are relatively rare. Females that carry the allele at the mating locus causing them to be attracted to such males then suffer a fitness cost due to lost mating opportunities. This mating allele is therefore purged, and in turn so is the recessive allele for B phenotype at the P locus. Under self-referencing and rejection rules, however, choosy females only reject males of a specific phenotype. They can therefore potentially mate with larger pool of males than females attracted to a single type. As a result, self-referencing and rejection rules are less sensitive to demographic effects and so are more conducive to disassortative mating evolution. In their final analysis, Maisonneuve *et al.* [5] investigate the influence of recombination among the P and mating loci. They show that recombination has different effects on disassortative mating evolution depending on the mechanism of mate choice. Under the self-referencing rule, loose linkage leads to higher levels of disassortative mating and polymorphism than when linkage is tight. Under attraction or rejection rule, however, even very limited recombination completely inhibits the evolution of disassortative mating. This is because, with alleles at the mating locus coding for attraction/rejection to specific males, recombination breaks the association between the P and mating loci necessary for disassortative mating. By contrast, disassortative mating via a self-referencing rule does not depend on the linkage among the P and mating loci: females choose males that are different to themselves independently from the alleles they carry at the P locus. Taken together, Maisonneuve *et al.*’s analyses [5] show that disassortative mating can readily evolve in a system like *H. numata*, but that this evolution depends on the genetic architecture of mating behavior. The architectures that are more conducive to the evolution of disassortative mating are: (1) epistatic interactions among the P and mating loci such that females are able to recognize their own phenotype and base their mating decision upon this information (self-referencing rule); and (2) full linkage among the P supergene and a mating locus that triggers rejection of a specific color pattern. While the mechanisms behind disassortative mating remain to be elucidated, assortative mating seems to rely on alleles triggering attraction to specific cues with variation in attraction and cues linked together [10]. These observations support the notion that disassortative mating is due to alleles causing rejection, in tight linkage to the P locus. If so, mating loci would in fact be part of the P supergene, thus controlling not only intricate wing color pattern but also mating behavior. Beyond the specific system of *H. numata*, Maisonneuve *et al.*’s study [5] helps understand the evolution of disassortative mating and its association with the genetic architecture of correlated traits. In particular, Maisonneuve *et al.* [5] expands the role of supergenes for ecologically relevant traits to mating behavior, further bolstering the relevance of these remarkable genetic elements in the maintenance of variation in complex and elaborate phenotypes. **References** [1] Merrill, R M, K K Dasmahapatra, J W Davey, D D Dell'Aglio, J J Hanly, B Huber, C D Jiggins, et al. (2015). The Diversification of Heliconius butterflies: What Have We Learned in 150 Years? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28 (8), 1417–38. [https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12672.](https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12672.) [2] Joron M, IR Wynne, G Lamas, and J Mallet (1999). Variable selection and the coexistence of multiple mimetic forms of the butterfly Heliconius numata. Evolutionary Ecology 13, 721– 754. [https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010875213123](https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010875213123) [3] Joron M and Y Iwasa (2005). The evolution of a Müllerian mimic in a spatially distributed community. Journal of Theoretical Biology 237, 87–103. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.04.005](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.04.005) [4] Chouteau M, V Llaurens, F Piron-Prunier, and M Joron (2017). Polymorphism at a mimicry su- pergene maintained by opposing frequency-dependent selection pressures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 8325–8329. [https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702482114](https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702482114) [5] Maisonneuve, L, Chouteau, M, Joron, M and Llaurens, V. (2020). Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantage. bioRxiv, 616409, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. [https://doi.org/10.1101/616409](https://doi.org/10.1101/616409) [6] Joron M, L Frezal, RT Jones, NL Chamberlain, SF Lee, CR Haag, A Whibley, M Becuwe, SW Baxter, L Ferguson, et al. (2011). Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic super- gene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477, 203. [https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10341](https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10341) [7] Schwander T, R Libbrecht, and L Keller (2014). Supergenes and Complex Phenotypes.” Current Biology. 24 (7), 288–94. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056.](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056.) [8] Jay P, M Chouteau, A Whibley, H Bastide, V Llaurens, H Parrinello, and M Joron (2019). Mutation accumulation in chromosomal inversions maintains wing pattern polymorphism in a butterfly. bioRxiv. [https://doi.org/ 10.1101/736504. ](https://doi.org/ 10.1101/736504. ) [9] Kopp M, MR Servedio, TC Mendelson, RJ Safran, RL Rodrıguez, ME Hauber, EC Scordato, LB Symes, CN Balakrishnan, DM Zonana, et al. (2018). Mechanisms of assortative mating in speciation with gene flow: connecting theory and empirical research. The American Naturalist 191, 1–20. [https://doi.org/10.1086/694889](https://doi.org/10.1086/694889) [10] Merrill RM, P Rastas, SH Martin, MC Melo, S Barker, J Davey, WO McMillan, and CD Jiggins (2019). Genetic dissection of assortative mating behavior. PLoS biology 17, e2005902. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2005902](https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2005902)

| Evolution and genetic architecture of disassortative mating at a locus under heterozygote advantage | Ludovic Maisonneuve, Mathieu Joron, Mathieu Chouteau and Violaine Llaurens | <p>The evolution of mate preferences may depend on natural selection acting on the mating cues and on the underlying genetic architecture. While the evolution of assortative mating with respect to locally adapted traits has been well-characterized... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Charles Mullon | | 2019-10-29 09:55:18 | View |

Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates

Rylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais

https://doi.org/10.1101/445072

Studying genetic antagonisms as drivers of genome evolution

Recommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Qi Zhou and 3 anonymous reviewers

Sex chromosomes are special in the genome because they are often highly differentiated over much of their lengths and marked by degenerative evolution of their gene content. Understanding why sex chromosomes differentiate requires deciphering the forces driving their recombination patterns. Suppression of recombination may be subject to selection, notably because of functional effects of locking together variation at different traits, as well as longer-term consequences of the inefficient purge of deleterious mutations, both of which may contribute to patterns of differentiation [1]. As an example, male and female functions may reveal intrinsic antagonisms over the optimal genotypes at certain genes or certain combinations of interacting genes. As a result, selection may favour the recruitment of rearrangements blocking recombination and maintaining the association of sex-antagonistic allele combinations with the sex-determining locus.

The hypothesis that sexually antagonistic selection might drive recombination suppression along the sex chromosomes is not new, but there are surprisingly few studies examining this empirically [1]. Support mainly comes from the study of guppy populations Poecilia reticulata in which the level of sexual dimorphism (notably due to male ornaments, subject to sexual selection) varies among populations, and was found to correlate with the length of the non-recombining region on the sex chromosome [2]. But the link is not always that clear. For instance in the fungus Microbotryum violaceum, the mating type loci is characterized by adjacent segments with recombination suppression, despite the near absence of functional differentiation between mating types [3].

In this study, Shearn and colleagues [4] explore the patterns of recombination suppression on the sex chromosomes of primates. X and Y chromosomes are strongly differentiated, except in a small region where they recombine with each other, the pseudoautosomal region (PAR). In the clade of apes and monkeys, including humans, large rearrangements have extended the non recombining region stepwise, eroding the PAR. Could this be driven by sexually antagonistic selection in a clade showing strong sexual differentiation?

To evaluate this idea, Shearn et al. have compared the structure of recombination in apes and monkeys to their sister clade with lower levels of sexual dimorphism, the lemurs and the lorises. If sexual antagonism was important in shaping recombination suppression, and assuming lower measures of sexual dimorphism reflect lower sexual antagonism [5], then lemurs and lorises would be predicted to show a shorter non-recombining region than apes and monkeys.

Lemurs and lorises were terra incognita in terms of genomic research on the sex chromosomes, so Shearn et al. have sequenced the genomes of males and females of different species. To assess whether sequences came from a recombining or non-recombining segment, they used coverage information in males vs females to identify sequences on the X whose copy on the Y is absent or too divergent to map, indicating long-term differentiation (absence of recombination). This approach reveals that the two lineages have undergone different recombination dynamics since they split from their common ancestor: regions which have undergone further structural rearrangements extending the non-recombining region in apes and monkeys, have continued to recombine normally in lemurs and lorises. Consistent with the prediction, macroevolutionary variation in the differentiation of males and females is indeed accompanied by variation in the size of the non-recombining region on the sex chromosome.

Sex chromosomes are excellent examples of how genomes are shaped by selection. By directly exploring recombination patterns on the sex chromosome across all extant primate groups, this study comes as a nice addition to the short series of empirical studies evaluating whether sexual antagonism may drive certain aspects of genome structure. The sexual selection causing sometimes spectacular morphological or behavioural differences between sexes in many animals may be the visible tip of the iceberg of all the antagonisms that characterise male vs. female functions generally [5]. Further research should bring insight into how different flavours or intensities of antagonistic selection can contribute to shape genome variation.

References

[1] Charlesworth D (2017) Evolution of recombination rates between sex chromosomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160456. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0456

[2] Wright AE, Darolti I, Bloch NI, Oostra V, Sandkam B, Buechel SD, Kolm N, Breden F, Vicoso B, Mank JE (2017) Convergent recombination suppression suggests role of sexual selection in guppy sex chromosome formation. Nature Communications, 8, 14251. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14251

[3] Branco S, Badouin H, Vega RCR de la, Gouzy J, Carpentier F, Aguileta G, Siguenza S, Brandenburg J-T, Coelho MA, Hood ME, Giraud T (2017) Evolutionary strata on young mating-type chromosomes despite the lack of sexual antagonism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 7067–7072. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701658114

[4] Shearn R, Wright AE, Mousset S, Régis C, Penel S, Lemaitre J-F, Douay G, Crouau-Roy B, Lecompte E, Marais GAB (2020) Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates. bioRxiv, 445072. https://doi.org/10.1101/445072

[5] Connallon T, Clark AG (2014) Evolutionary inevitability of sexual antagonism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281, 20132123. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2123

| Evolutionary stasis of the pseudoautosomal boundary in strepsirrhine primates | Rylan Shearn, Alison E. Wright, Sylvain Mousset, Corinne Régis, Simon Penel, Jean-François Lemaitre, Guillaume Douay, Brigitte Crouau-Roy, Emilie Lecompte, Gabriel A.B. Marais | <p>Sex chromosomes are typically comprised of a non-recombining region and a recombining pseudoautosomal region. Accurately quantifying the relative size of these regions is critical for sex chromosome biology both from a functional (i.e. number o... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Mathieu Joron | | 2019-02-04 15:16:32 | View |

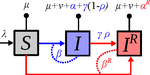

Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France

Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie van der Werf, Bruno Lina, Laurence Josset, Vincent Enouf, Samuel Alizon and the COVID SMIT PSL group

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

SARS-Cov-2 genome sequence analysis suggests rapid spread followed by epidemic slowdown in France

Recommended by B. Jesse Shapiro based on reviews by Luca Ferretti and 2 anonymous reviewers

Sequencing and analyzing SARS-Cov-2 genomes in nearly real time has the potential to quickly confirm (and inform) our knowledge of, and response to, the current pandemic [1,2]. In this manuscript [3], Danesh and colleagues use the earliest set of available SARS-Cov-2 genome sequences available from France to make inferences about the timing of the major epidemic wave, the duration of infections, and the efficacy of lockdown measures. Their phylodynamic estimates -- based on fitting genomic data to molecular clock and transmission models -- are reassuringly close to estimates based on 'traditional' epidemiological methods: the French epidemic likely began in mid-January or early February 2020, and spread relatively rapidly (doubling every 3-5 days), with people remaining infectious for a median of 5 days [4,5]. These transmission parameters are broadly in line with estimates from China [6,7], but are currently unknown in France (in the absence of contact tracing data). By estimating the temporal reproductive number (Rt), the authors detected a slowing down of the epidemic in the most recent period of the study, after mid-March, supporting the efficacy of lockdown measures.

Along with the three other reviewers of this manuscript, I was impressed with the careful and exhaustive phylodynamic analyses reported by Danesh et al. [3]. Notably, they take care to show that the major results are robust to the choice of priors and to sampling. The authors are also careful to note that the results are based on a limited sample size of SARS-Cov-2 genomes, which may not be representative of all regions in France. Their analysis also focused on the dominant SARS-Cov-2 lineage circulating in France, which is also circulating in other countries. The variations they inferred in epidemic growth in France could therefore be reflective on broader control policies in Europe, not only those in France. Clearly more work is needed to fully unravel which control policies (and where) were most effective in slowing the spread of SARS-Cov-2, but Danesh et al. [3] set a solid foundation to build upon with more data. Overall this is an exemplary study, enabled by rapid and open sharing of sequencing data, which provides a template to be replicated and expanded in other countries and regions as they deal with their own localized instances of this pandemic.

References

[1] Grubaugh, N. D., Ladner, J. T., Lemey, P., Pybus, O. G., Rambaut, A., Holmes, E. C., & Andersen, K. G. (2019). Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nature microbiology, 4(1), 10-19. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0296-2

[2] Fauver et al. (2020) Coast-to-Coast Spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the Early Epidemic in the United States. Cell, 181(5), 990-996.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.021

[3] Danesh, G., Elie, B., Michalakis, Y., Sofonea, M. T., Bal, A., Behillil, S., Destras, G., Boutolleau, D., Burrel, S., Marcelin, A.-G., Plantier, J.-C., Thibault, V., Simon-Loriere, E., van der Werf, S., Lina, B., Josset, L., Enouf, V. and Alizon, S. and the COVID SMIT PSL group (2020) Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemic in France. medRxiv, 2020.06.03.20119925, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20119925

[4] Salje et al. (2020) Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-02548181

[5] Sofonea, M. T., Reyné, B., Elie, B., Djidjou-Demasse, R., Selinger, C., Michalakis, Y. and Samuel Alizon, S. (2020) Epidemiological monitoring and control perspectives: application of a parsimonious modelling framework to the COVID-19 dynamics in France. medRxiv, 2020.05.22.20110593. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.22.20110593

[6] Rambaut, A. (2020) Phylogenetic analysis of nCoV-2019 genomes. virological.org/t/phylodynamic-analysis-176-genomes-6-mar-2020/356

[7] Li et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med, 382: 1199-1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

| Early phylodynamics analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics in France | Gonché Danesh, Baptiste Elie,Yannis Michalakis, Mircea T. Sofonea, Antonin Bal, Sylvie Behillil, Grégory Destras, David Boutolleau, Sonia Burrel, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Jean-Christophe Plantier, Vincent Thibault, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Sylvie va... | <p>France was one of the first countries to be reached by the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we analyse 196 SARS-Cov-2 genomes collected between Jan 24 and Mar 24 2020, and perform a phylodynamics analysis. In particular, we analyse the doubling time, r... |  | Evolutionary Epidemiology, Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | B. Jesse Shapiro | | 2020-06-04 13:13:57 | View |

Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

DNA transposons drive genome evolution of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita

Recommended by Ines Alvarez based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

Duplications, mutations and recombination may be considered the main sources of genomic variation and evolution. In addition, sexual recombination is essential in purging deleterious mutations and allowing advantageous allelic combinations to occur (Glémin et al. 2019). However, in parthenogenetic asexual organisms, variation cannot be explained by sexual recombination, and other mechanisms must account for it. Although it is known that transposable elements (TE) may influence on genome structure and gene expression patterns, their role as a primary source of genomic variation and rapid adaptability has received less attention. An important role of TE on adaptive genome evolution has been documented for fungal phytopathogens (Faino et al. 2016), suggesting that TE activity might explain the evolutionary dynamics of this type of organisms.

The phytopathogen nematode Meloidogyne incognita is one of the worst agricultural pests in warm climates (Savary et al. 2019). This species, as well as other root-knot nematodes (RKN), shows a wide geographical distribution range infecting diverse groups of plants. Although allopolyploidy may have played an important role on the wide adaptation of this phytopathogen, it may not explain by itself the rapid changes required to overcome plant resistance in a few generations. Paradoxically, M. incognita reproduces asexually via mitotic parthenogenesis (Trudgill and Blok 2001; Castagnone-Sereno and Danchin 2014) and only few single nucleotide variations were identified between different host races isolates (Koutsovoulos et al. 2020). Therefore, this is an interesting model to explore other sources of genomic variation such the TE activity and its role on the success and adaptability of this phytopathogen.

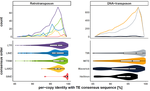

To address these questions, Kozlowski et al. (2020) estimated the TE mobility across 12 geographical isolates that presented phenotypic variations in Meloidogyne incognita, concluding that recent activity of TE in both genic and regulatory regions might have given rise to relevant functional differences between genomes. This was the first estimation of TE activity as a mechanism probably involved in genome plasticity of this root-knot nematode. This study also shed light on evolutionary mechanisms of asexual organisms with an allopolyploid origin. These authors re-annotated the 185 Mb triploid genome of M. incognita for TE content analysis using stringent filters (Kozlowski 2020a), and estimated activity by their distribution using a population genomics approach including isolates from different crops and locations. Canonical TE represented around 4.7% of the M. incognita genome of which mostly correspond to TIR (Terminal Inverted Repeats) and MITEs (Miniature Inverted repeat Transposable Elements) followed by Maverick DNA transposons and LTR (Long Terminal Repeats) retrotransposons. The result that most TE found were represented by DNA transposons is similar to the previous studies with the nematode species model Caenorhabditis elegans (Bessereau 2006; Kozlowski 2020b) and other nematodes as well. Canonical TE annotations were highly similar to their consensus sequences containing transposition machinery when TE are autonomous, whereas no genes involved in transposition were found in non-autonomous ones. These findings suggest recent activity of TE in the M. incognita genome. Other relevant result was the significant variation in TE presence frequencies found in more than 3,500 loci across isolates, following a bimodal distribution within isolates. However, variation in TE frequencies was low to moderate between isolates recapitulating the phylogenetic signal of isolates DNA sequences polymorphisms. A detailed analysis of TE frequencies across isolates allowed identifying polymorphic TE loci, some of which might be neo-insertions mostly of TIRs and MITEs (Kozlowski 2020c). Interestingly, the two thirds of the fixed neo-insertions were located in coding regions or in regulatory regions impacting expression of specific genes in M. incognita. Future research on proteomics is needed to evaluate the functional impact that these insertions have on adaptive evolution in M. incognita. In this line, this pioneer research of Kozlowski et al. (2020) is a first step that is also relevant to remark the role that allopolyploidy and reproduction have had on shaping nematode genomes.

References

[1] Bessereau J-L. 2006. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1

[2] Castagnone-Sereno P, Danchin EGJ. 2014. Parasitic success without sex - the nematode experience. J. Evol. Biol. 27:1323-1333. 10.1111/jeb.12337

[3] Faino L, Seidl MF, Shi-Kunne X, Pauper M, Berg GCM van den, Wittenberg AHJ, Thomma BPHJ. 2016. Transposons passively and actively contribute to evolution of the two-speed genome of a fungal pathogen. Genome Res. 26:1091-1100. 10.1101/gr.204974.116

[4] Glémin S, François CM, Galtier N. 2019. Genome Evolution in Outcrossing vs. Selfing vs. Asexual Species. In: Anisimova M, editor. Evolutionary Genomics: Statistical and Computational Methods. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Springer. p. 331-369. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9074-0_11

[5] Koutsovoulos GD, Marques E, Arguel M-J, Duret L, Machado ACZ, Carneiro RMDG, Kozlowski DK, Bailly-Bechet M, Castagnone-Sereno P, Albuquerque EVS, et al. 2020. Population genomics supports clonal reproduction and multiple independent gains and losses of parasitic abilities in the most devastating nematode pest. Evol. Appl. 13:442-457. 10.1111/eva.12881

[6] Kozlowski D. 2020a. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the M. incognita genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EPTDOS

[7] Kozlowski D. 2020b. Transposable Elements prediction and annotation in the C. elegans genome. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/LQCIW0

[8] Kozlowski D. 2020c. TE polymorphisms detection and analysis with PopoolationTE2. Portail Data INRAE. 10.15454/EWJCT8

[9] Kozlowski DK, Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen R, Da Rocha M, Koutsovoulos GD, Bailly-Bechet M, Danchin EG (2020) Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. bioRxiv, 2020.04.30.069948, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. 10.1101/2020.04.30.069948

[10] Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. 2019. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3:430-439. 10.1038/s41559-018-0793-y

[11] Trudgill DL, Blok VC. 2001. Apomictic, polyphagous root-knot nematodes: exceptionally successful and damaging biotrophic root pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 39:53-77. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.39.1.53

| Transposable Elements are an evolutionary force shaping genomic plasticity in the parthenogenetic root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita | Djampa KL Kozlowski, Rahim Hassanaly-Goulamhoussen, Martine Da Rocha, Georgios D Koutsovoulos, Marc Bailly-Bechet, Etienne GJ Danchin | <p>Despite reproducing without sexual recombination, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is adaptive and versatile. Indeed, this species displays a global distribution, is able to parasitize a large range of plants and can overcome plant ... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Ines Alvarez | | 2020-05-04 11:43:14 | View |

Y chromosome makes fruit flies die younger

Recommended by Gabriel Marais, Jean-François Lemaitre and Cristina Vieira

In most animal species, males and females display distinct survival prospect, a phenomenon known as sex gap in longevity (SGL, Marais et al. 2018). The study of SGLs is crucial not only for having a full picture of the causes underlying organisms’ health, aging and death but also to initiate the development of sex-specific anti-aging interventions in humans (Austad and Bartke 2015). Three non-mutually evolutionary causes have been proposed to underlie SGLs (Marais et al. 2018). First, SGLs could be the consequences of sex-differences in life history strategies. For example, evolving dimorphic traits (e.g. body size, ornaments or armaments) may imply unequal physiological costs (e.g. developmental, maintenance) between the sexes and this may result in differences in longevity and aging. Second, mitochondria are usually transmitted by the mother and thus selection is blind to mitochondrial deleterious mutations affecting only males. Such mutations can freely accumulate in the mitochondrial genome and may reduce male longevity, a phenomenon called the mother’s curse (Frank and Hurst 1996). Third, in species with sex chromosomes, all recessive deleterious mutations will be expressed on the single X chromosome in XY males and may reduce their longevity (the unguarded X effect). In addition, the numerous transposable elements (TEs) on the Y chromosome may affect aging. TE activity is normally repressed by epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modifications and small RNAs). However, it is known that this regulation is disrupted with increasing age. Because of the TE-rich Y chromosome, more TEs may become active in old males than in old females, generating more somatic mutations, accelerating aging and reducing longevity in males (the toxic Y effect, Marais et al. 2018).

The relative contributions of these different effects to SGLs remain unknown. Sex-differences in life history strategies have been considered as the most important cause of SGLs for long (Tidière et al. 2015) but this effect remain equivocal (Lemaître et al. 2020) and cannot explain alone the diversity of patterns observed across species (Marais et al. 2018). Similarly, while studies in Drosophila and humans have shown that the mother’s curse contributes to SGLs in those organisms (e.g. Milot et al. 2007), its contribution may not be strong. Recently, two large-scale comparative analyses have shown that in species with XY chromosomes males show a shorter lifespan compared to females, while in species with ZW chromosomes (a system in which the female are the heterogametic sex and are ZW, and the males ZZ) the opposite pattern is observed (Pipoly et al. 2015; Xirocostas et al. 2020). Apart from these correlational studies, very little experimental tests of the effect of sex chromosomes on longevity have been conducted. In Drosophila, the evidence suggests that the unguarded X effect does not contribute to SGLs (Brengdahl et al. 2018). Whether a toxic Y effect exists in this species was unknown.

In a very elegant study, Brown et al. (2020) provided strong evidence for such a toxic Y effect in Drosophila melanogaster. First, they checked that in the D. melanogaster strain that they were studying (Canton-S), males were indeed dying younger than females. They also confirmed that in this strain, as in others, the male genomes include more repeats and heterochromatin than the female ones using cytometry. A careful analysis of the heterochromatin (using H3K9me2, a repressive histone modification typical of heterochromatin, as a proxy) in old flies revealed that heterochromatin loss was much more important in males than in females, in particular on the Y chromosome (but also to a lesser extent at the pericentromric regions of the autosomes). This change in heterochromatin had two outputs, they found. First, the expression of the genes in those regions was affected. They highlighted that many of such genes are involved in immunity and regulation with a potential impact on longevity. Second, they found a striking TE reactivation. These two effects were stronger in males. While females showed clear reactivation of 6 TEs, with the total fraction of repeats in the transcriptome going from 2% (young females) to 4.6% (old females), males experienced the reactivation of 32 TEs, with the total fraction of repeats in the transcriptome going from 1.6% (young males) to 5.8% (old males). It appeared that most of these TEs are Y-linked. And when focusing on Y-linked repeats, they found that 32 Y-linked TEs became upregulated during male aging and the fraction of Y-linked TEs in the transcriptome increased ninefold.

All these observations clearly suggested that male longevity was decreased because of a toxic Y effect. To really uncover a causal relationship between having a Y chromosome and shorter longevity, Brown et al. (2020) artificially produced flies with atypical karyotypes: X0 males, XXY females and XYY males. This is very interesting as they could uncouple the effect of the phenotypical sex (being male or female) and having a Y chromosome or not, as in fruit flies sex is determined not by the Y chromosome but by the X/autosome ratio. Their results are striking. They found that longevity of the X0 males was the highest (higher than XX females in fact), and that of the XYY males the lowest. Females XXY had intermediate longevities. Importantly, this was found to be robust to genomic background as results were the same using crosses from different strains. When analysing TEs of these flies, they found a particularly strong expression of the Y-linked TEs in old XXY and XYY flies. Interestingly, in young XXY and XYY flies Y-linked TEs expression was also strong, suggesting the chromatin regulation of the Y chromosome is disrupted in these flies.

This work points to the idea that SGLs in D. melanogaster are mainly explained by the toxic Y effect. The molecular details however remain to be elucidated. The effect of the Y chromosome on aging might be more complex than envisioned in the toxic Y model presented above. Brown et al. (2020) indeed found that heterochromatin loss was globally faster in males, both at the Y chromosome and the autosomes. The organisation of the nucleus, in particular of the nucleolus, which is involved in heterochromatin maintenance, involves the sex chromosomes in D. melanogaster as discussed in the paper, and may explain this observation. The epigenetic status of the Y chromosome is known to affect that of all the autosomes in Drosophila (Lemos et al. 2008). Also, in Brown et al. (2020) most of the work (in particular the genomic part) has been done on Canton-S. Only D. melanogaster was studied but limited data suggest different Drosophila species may have different SGLs. The TE analysis is known to be tricky, different tools to analyse TE expression exist (e.g. Lerat et al. 2017; Lanciano and Cristofari 2020). Future work should focus on testing the toxic Y effect on other D. melanogaster strains and other Drosophila species, using different tools to study TE expression, and on dissecting the molecular details of the toxic Y effect.

References

Austad, S. N., and Bartke, A. (2015). Sex differences in longevity and in responses to anti-aging interventions: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 62(1), 40–46. 10.1159/000381472

Brengdahl, M., Kimber, C. M., Maguire-Baxter, J., and Friberg, U. (2018). Sex differences in life span: Females homozygous for the X chromosome do not suffer the shorter life span predicted by the unguarded X hypothesis. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution, 72(3), 568–577. 10.1111/evo.13434

Brown, E. J., Nguyen, A. H., and Bachtrog, D. (2020). The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila. Nature ecology and evolution, 4(6), 853–862. 10.1038/s41559-020-1179-5 or preprint link on bioRxiv

Frank, S. A., and Hurst, L. D. (1996). Mitochondria and male disease. Nature, 383(6597), 224. 10.1038/383224a0

Lanciano, S., and Cristofari, G. (2020). Measuring and interpreting transposable element expression. Nature reviews. Genetics, 10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y. Advance online publication. 10.1038/s41576-020-0251-y

Lemaître, J. F., Ronget, V., Tidière, M., Allainé, D., Berger, V., Cohas, A., Colchero, F., Conde, D. A., Garratt, M., Liker, A., Marais, G., Scheuerlein, A., Székely, T., and Gaillard, J. M. (2020). Sex differences in adult lifespan and aging rates of mortality across wild mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(15), 8546–8553. 10.1073/pnas.1911999117

Lemos, B., Araripe, L. O., and Hartl, D. L. (2008). Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences. Science (New York, N.Y.), 319(5859), 91–93. 10.1126/science.1148861

Lerat, E., Fablet, M., Modolo, L., Lopez-Maestre, H., and Vieira, C. (2017). TEtools facilitates big data expression analysis of transposable elements and reveals an antagonism between their activity and that of piRNA genes. Nucleic acids research, 45(4), e17. 10.1093/nar/gkw953

Marais, G., Gaillard, J. M., Vieira, C., Plotton, I., Sanlaville, D., Gueyffier, F., and Lemaitre, J. F. (2018). Sex gap in aging and longevity: can sex chromosomes play a role?. Biology of sex differences, 9(1), 33. 10.1186/s13293-018-0181-y

Milot, E., Moreau, C., Gagnon, A., Cohen, A. A., Brais, B., and Labuda, D. (2017). Mother's curse neutralizes natural selection against a human genetic disease over three centuries. Nature ecology and evolution, 1(9), 1400–1406. 10.1038/s41559-017-0276-6

Pipoly, I., Bókony, V., Kirkpatrick, M., Donald, P. F., Székely, T., and Liker, A. (2015). The genetic sex-determination system predicts adult sex ratios in tetrapods. Nature, 527(7576), 91–94. 10.1038/nature15380

Tidière, M., Gaillard, J. M., Müller, D. W., Lackey, L. B., Gimenez, O., Clauss, M., and Lemaître, J. F. (2015). Does sexual selection shape sex differences in longevity and senescence patterns across vertebrates? A review and new insights from captive ruminants. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution, 69(12), 3123–3140. 10.1111/evo.12801

Xirocostas, Z. A., Everingham, S. E., and Moles, A. T. (2020). The sex with the reduced sex chromosome dies earlier: a comparison across the tree of life. Biology letters, 16(3), 20190867. 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0867

| The Y chromosome may contribute to sex-specific ageing in Drosophila | Emily J Brown, Alison H Nguyen, Doris Bachtrog | <p>Heterochromatin suppresses repetitive DNA, and a loss of heterochromatin has been observed in aged cells of several species, including humans and *Drosophila*. Males often contain substantially more heterochromatic DNA than females, due to the ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Expression Studies, Genetic conflicts, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Reproduction and Sex | Gabriel Marais | | 2020-07-28 15:06:18 | View |

An evolutionary view of a biomedically important gene family

Recommended by Kateryna Makova based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

This manuscript [1] investigates the evolutionary history of the DAN gene family—a group of genes important for embryonic development of limbs, kidneys, and left-right axis speciation. This gene family has also been implicated in a number of diseases, including cancer and nephropathies. DAN genes have been associated with the inhibition of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. Despite this detailed biochemical and functional knowledge and clear importance for development and disease, evolution of this gene family has remained understudied. The diversification of this gene family was investigated in all major groups of vertebrates. The monophyly of the gene members belonging to this gene family was confirmed. A total of five clades were delineated, and two novel lineages were discovered. The first lineage was only retained in cephalochordates (amphioxus), whereas the second one (GREM3) was retained by cartilaginous fish, holostean fish, and coelanth. Moreover, the patterns of chromosomal synteny in the chromosomal regions harboring DAN genes were investigated. Additionally, the authors reconstructed the ancestral gene repertoires and studied the differential retention/loss of individual gene members across the phylogeny. They concluded that the ancestor of gnathostome vertebrates possessed eight DAN genes that underwent differential retention during the evolutionary history of this group. During radiation of vertebrates, GREM1, GREM2, SOST, SOSTDC1, and NBL1 were retained in all major vertebrate groups. At the same time, GREM3, CER1, and DAND5 were differentially lost in some vertebrate lineages. At least two DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of vertebrates, and at least three DAN genes were present in the common ancestor of chordates. Therefore the patterns of retention and diversification in this gene family appear to be complex. Evolutionary slowdown for the DAN gene family was observed in mammals, suggesting selective constraints. Overall, this article puts the biomedical importance of the DAN family in the evolutionary perspective.

References

[1] Opazo JC, Hoffmann FG, Zavala K, Edwards SV (2020) Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates. bioRxiv, 794404, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/794404

| Evolution of the DAN gene family in vertebrates | Juan C. Opazo, Federico G. Hoffmann, Kattina Zavala, Scott V. Edwards | <p>The DAN gene family (DAN, Differential screening-selected gene Aberrant in Neuroblastoma) is a group of genes that is expressed during development and plays fundamental roles in limb bud formation and digitation, kidney formation and morphogene... |  | Molecular Evolution | Kateryna Makova | | 2019-10-15 16:43:13 | View |

Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emmanuelle d'Alencon, Nicolas Nègre

https://doi.org/10.1101/263186

Speciation through selection on mitochondrial genes?

Recommended by Astrid Groot based on reviews by Heiko Vogel and Sabine Haenniger

Whether speciation through ecological specialization occurs has been a thriving research area ever since Mayr (1942) stated this to play a central role. In herbivorous insects, ecological specialization is most likely to happen through host plant differentiation (Funk et al. 2002). Therefore, after Dorothy Pashley had identified two host strains in the Fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, in 1988 (Pashley 1988), researchers have been trying to decipher the evolutionary history of these strains, as this seems to be a model species in which speciation is currently occurring through host plant specialization. Even though FAW is a generalist, feeding on many different host plant species (Pogue 2002) and a devastating pest in many crops, Pashley identified a so-called corn strain and a so-called rice strain in Puerto Rico. Genetically, these strains were found to differ mostly in an esterase, although later studies showed additional genetic differences and markers, mostly in the mitochondrial COI and the nuclear TPI. Recent genomic studies showed that the two strains are overall so genetically different (2% of their genome being different) that these two strains could better be called different species (Kergoat et al. 2012). So far, the most consistent differences between the strains have been their timing of mating activities at night (Schoefl et al. 2009, 2011; Haenniger et al. 2019) and hybrid incompatibilities (Dumas et al. 2015; Kost et al. 2016). Whether and to what extent host plant preference or performance contributed to the differentiation of these sympatrically occurring strains has remained unclear.

In the current study, Orsucci et al. (2020) performed oviposition assays and reciprocal transplant experiments with both strains to measure fitness effects, in combination with a comprehensive RNAseq experiment, in which not only lab reared larvae were analysed, but also field-collected larvae. When testing preference and performance on the two host plants corn and rice, the authors did not find consistent fitness differences between the two strains, with both strains performing less on rice plants, although larvae from the corn strain survived more on corn plants than those from the rice strain. These results mostly confirm findings of a number of investigations over the past 30 years, where no consistent differences on the two host plants were observed (reviewed in Groot et al. 2016). However, the RNAseq experiments did show some striking differences between the two strains, especially in the reciprocally transplanted larvae, where both strains had been reared on rice or on corn plants for one generation: both strains showed transcriptional responses that correspond to their respective putative host plants, i.e. overexpression of genes involved in digestion and metabolic activity, and underexpression of genes involved in detoxification, in the corn strain on corn and in the rice strain on rice. Interestingly, similar sets of genes were found to be overexpressed in the field-collected larvae with which a RNAseq experiment was conducted as well.

The most interesting result of the study performed by Orsucci et al. (2020) is the underexpression in the corn strain of so-called numts, small genomic sequences that corresponded to fragments of the mitochondrial COI and COIII. These two numts were differentially expressed in the two strains in all RNAseq experiments analysed. This result coincides with the fact that the COI is one of the main diagnostic markers to distinguish these two strains. The authors suggestion that a difference in energy production between these two strains may be linked to a shift in host plant preference matches their finding that rice plants seem to be less suitable host plants than corn plants. However, as the lower suitability of rice plants was true for both strains, it remains unclear whether and how this difference could be linked to possible host plant differentiation between the strains. The authors also suggest that COI and potentially other mitochondrial genes may be the original target of selection between these two strains. This is especially interesting in light of the fact that field-collected larvae have frequently been found to have a rice strain mitochondrial genotype and a corn strain nuclear genotype, also in this study, while in the lab (female rice strain x male corn strain) hybrid females (i.e. females with a rice strain mitochondrial genotype and a corn strain nuclear genotype) are behaviorally sterile (Kost et al. 2016). Whether and how selection on mitochondrial genes or on mitonuclear interactions has indeed affected the evolution of these strains in the New world, and will affect the evolution of FAW in newly invaded habitats in the Old world, including Asia and Australia – where, so far, only corn strain and (female rice strain x male corn strain) hybrids have been found (Nagoshi 2019), will be a challenging research question for the coming years.

References

[1] Dumas, P. et al. (2015). Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host-plant variants: two host strains or two distinct species?. Genetica, 143(3), 305-316. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9829-2

[2] Funk, D. J., Filchak, K. E. and Feder J. L. (2002) Herbivorous insects: model systems for the comparative study of speciation ecology. In: Etges W.J., Noor M.A.F. (eds) Genetics of Mate Choice: From Sexual Selection to Sexual Isolation. Contemporary Issues in Genetics and Evolution, vol 9. Springer, Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0265-3_10

[3] Groot, A. T., Unbehend, M., Hänniger, S., Juárez, M. L., Kost, S. and Heckel D. G.(2016) Evolution of reproductive isolation of Spodoptera frugiperda. In Allison, J. and Cardé, R. (eds) Sexual communication in moths. Chapter 20: 291-300.

[4] Hänniger, S. et al. (2017). Genetic basis of allochronic differentiation in the fall armyworm. BMC evolutionary biology, 17(1), 68. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0911-5

[5] Kost, S., Heckel, D. G., Yoshido, A., Marec, F., and Groot, A. T. (2016). AZ‐linked sterility locus causes sexual abstinence in hybrid females and facilitates speciation in Spodoptera frugiperda. Evolution, 70(6), 1418-1427. doi: 10.1111/evo.12940

[6] Mayr, E. (1942) Systematics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York.

[7] Nagoshi, R. N. (2019). Evidence that a major subpopulation of fall armyworm found in the Western Hemisphere is rare or absent in Africa, which may limit the range of crops at risk of infestation. PloS one, 14(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208966

[8] Orsucci, M., Moné, Y., Audiot, P., Gimenez, S., Nhim, S., Naït-Saïdi, R., Frayssinet, M., Dumont, G., Boudon, J.-P., Vabre, M., Rialle, S., Koual, R., Kergoat, G. J., Nagoshi, R. N., Meagher, R. L., d’Alençon, E. and Nègre N. (2020) Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). bioRxiv, 263186, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evol Biol. doi: 10.1101/263186

[9] Pashley, D. P. (1988) Current Status of Fall Armyworm Host Strains. Florida Entomologist 71 (3): 227–34. doi: 10.2307/3495425

[10] Pogue, M. (2002). A World Revision of the Genus Spodoptera Guenée (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). American Entomological Society.

[11] Schöfl, G., Heckel, D. G., and Groot, A. T. (2009). Time‐shifted reproductive behaviours among fall armyworm (Noctuidae: Spodoptera frugiperda) host strains: evidence for differing modes of inheritance. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(7), 1447-1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01759.x

[12] Schöfl, G., Dill, A., Heckel, D. G., and Groot, A. T. (2011). Allochronic separation versus mate choice: nonrandom patterns of mating between fall armyworm host strains. The American Naturalist, 177(4), 470-485. doi: 10.1086/658904

| Transcriptional differences between the two host strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) | Marion Orsucci, Yves Moné, Philippe Audiot, Sylvie Gimenez, Sandra Nhim, Rima Naït-Saïdi, Marie Frayssinet, Guillaume Dumont, Jean-Paul Boudon, Marin Vabre, Stéphanie Rialle, Rachid Koual, Gael J. Kergoat, Rodney N. Nagoshi, Robert L. Meagher, Emm... | <p>Spodoptera frugiperda, the fall armyworm (FAW), is an important agricultural pest in the Americas and an emerging pest in sub-Saharan Africa, India, East-Asia and Australia, causing damage to major crops such as corn, sorghum and soybean. While... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Expression Studies, Life History, Speciation | Astrid Groot | | 2018-05-09 13:04:34 | View |

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Daniel Vitales and 2 anonymous reviewers