Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Mar 2020

Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree speciesAndrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur https://doi.org/10.1101/807727Remarkable insights into processes shaping African tropical tree diversityRecommended by Michael Pirie based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas based on reviews by Miguel de Navascués, Lars Chatrou and Oscar Vargas

Tropical biodiversity is immense, under enormous threat, and yet still poorly understood. Global climatic breakdown and habitat destruction are impacting on and removing this diversity before we can understand how the biota responds to such changes, or even fully appreciate what we are losing [1]. This is particularly the case for woody shrubs and trees [2] and for the flora of tropical Africa [3]. Helmstetter et al. [4] have taken a significant step to improve our understanding of African tropical tree diversity in the context of past climatic change. They have done so by means of a remarkably in-depth analysis of one species of the tropical plant family Annonaceae: Annickia affinis [5]. A. affinis shows a distribution pattern in Africa found in various plant (but interestingly not animal) groups: a discontinuity between north and south of the equator [6]. There is no obvious physical barrier to cause this discontinuity, but it does correspond with present day distinct northern and southern rainy seasons. Various explanations have been proposed for this discontinuity, set out as hypotheses to be tested in this paper: climatic fluctuations resulting in changes in plant distributions in the Pleistocene, or differences in flowering times or in ecological niche between northerly and southerly populations. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, but they can be tested using phylogenetic inference – if you can sample variable enough sequence data from enough individuals – complemented with analysis of ecological niches and traits. Using targeted sequence capture, the authors amassed a dataset representing 351 nuclear markers for 112 individuals of A. affinis. This dataset is impressive for a number of reasons: First, sampling such a species across such a wide range in tropical Africa presents numerous challenges of itself. Second, the technical achievement of using this still relatively new sequencing technique with a custom set of baits designed specifically for this plant family [7] is also considerable. The result is a volume of data that just a few years ago would not have been feasible to collect, and which now offers the possibility to meaningfully analyse DNA sequence variation within a species across numerous independent loci of the nuclear genome. This is the future of our research field, and the authors have ably demonstrated some of its possibilities. Using this data, they performed on the one hand different population genetic clustering approaches, and on the other, different phylogenetic inference methods. I would draw attention to their use and comparison of coalescence and network-based approaches, which can account for the differences between gene trees that might be expected between populations of a single species. The results revealed four clades and a consistent sequence of divergences between them. The authors inferred past shifts in geographic range (using a continuous state phylogeographic model), depicting a biogeographic scenario involving a dispersal north over the north/south discontinuity; and demographic history, inferring in some (but not all) lineages increases in effective population size around the time of the last glacial maximum, suggestive of expansion from refugia. Using georeferenced specimen data, they compared ecological niches between populations, discovering that overlap was indeed smallest comparing north to south. Just the phenology results were effectively inconclusive: far better data on flowering times is needed than can currently be harvested from digitised herbarium specimens. Overall, the results add to the body of evidence for the impact of Pleistocene climatic changes on population structure, and for niche differences contributing to the present day north/south discontinuity. However, they also paint a complex picture of idiosyncratic lineage-specific responses, even within a single species. With the increasing accessibility of the techniques used here we can look forward to more such detailed analyses of independent clades necessary to test and to expand on these conclusions, better to understand the nature of our tropical plant diversity while there is still opportunity to preserve it for future generations. References [1] Mace, G. M., Gittleman, J. L., and Purvis, A. (2003). Preserving the Tree of Life. Science, 300(5626), 1707–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1085510 | Phylogenomic approaches reveal how a climatic inversion and glacial refugia shape patterns of diversity in an African rain forest tree species | Andrew J. Helmstetter, Biowa E. N. Amoussou, Kevin Bethune, Narcisse G. Kandem, Romain Glèlè Kakaï, Bonaventure Sonké, Thomas L. P. Couvreur | <p>The world’s second largest expanse of tropical rain forest is in Central Africa and it harbours enormous species diversity. Population genetic studies have consistently revealed significant structure across central African rain forest plants, i... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Phylogeography & Biogeography | Michael Pirie | 2019-10-29 15:19:36 | View | |

17 Feb 2020

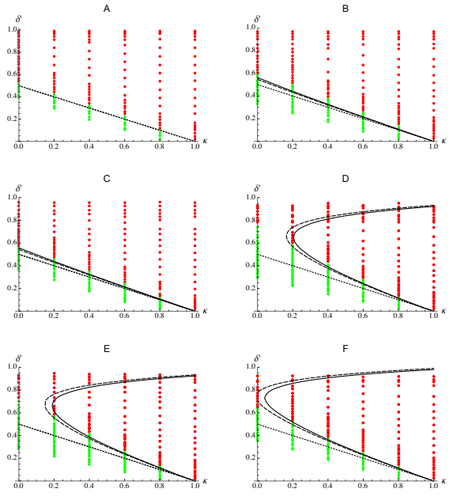

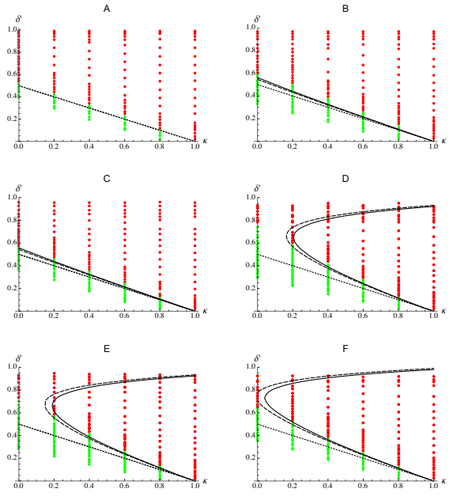

Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilizationDiala Abu Awad and Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/809814Epistasis and the evolution of selfingRecommended by Sylvain Gandon based on reviews by Nick Barton and 1 anonymous reviewerThe evolution of selfing results from a balance between multiple evolutionary forces. Selfing provides an "automatic advantage" due to the higher efficiency of selfers to transmit their genes via selfed and outcrossed offspring. Selfed offspring, however, may suffer from inbreeding depression. In principle the ultimate evolutionary outcome is easy to predict from the relative magnitude of these two evolutionary forces [1,2]. Yet, several studies explicitly taking into account the genetic architecture of inbreeding depression noted that these predictions are often too restrictive because selfing can evolve in a broader range of conditions [3,4]. References [1] Holsinger, K. E., Feldman, M. W., and Christiansen, F. B. (1984). The evolution of self-fertilization in plants: a population genetic model. The American Naturalist, 124(3), 446-453. doi: 10.1086/284287 | Epistasis, inbreeding depression and the evolution of self-fertilization | Diala Abu Awad and Denis Roze | <p>Inbreeding depression resulting from partially recessive deleterious alleles is thought to be the main genetic factor preventing self-fertilizing mutants from spreading in outcrossing hermaphroditic populations. However, deleterious alleles may... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Sylvain Gandon | 2019-10-18 09:29:41 | View | |

23 Jan 2020

A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model systemGillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. https://doi.org/10.1101/638288Improving the reliability of genotyping of multigene families in non-model organismsRecommended by François Rousset based on reviews by Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Helena Westerdahl and Thomas BigotThe reliability of published scientific papers has been the topic of much recent discussion, notably in the biomedical sciences [1]. Although small sample size is regularly pointed as one of the culprits, big data can also be a concern. The advent of high-throughput sequencing, and the processing of sequence data by opaque bioinformatics workflows, mean that sequences with often high error rates are produced, and that exact but slow analyses are not feasible. References [1] Ioannidis, J. P. A, Greenland, S., Hlatky, M. A., Khoury, M. J., Macleod, M. R., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. and Tibshirani, R. (2014) Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. The Lancet, 383, 166-175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8 | A novel workflow to improve multi-locus genotyping of wildlife species: an experimental set-up with a known model system | Gillingham, Mark A. F., Montero, B. Karina, Wilhelm, Kerstin, Grudzus, Kara, Sommer, Simone and Santos, Pablo S. C. | <p>Genotyping novel complex multigene systems is particularly challenging in non-model organisms. Target primers frequently amplify simultaneously multiple loci leading to high PCR and sequencing artefacts such as chimeras and allele amplification... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Ecology, Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution | François Rousset | Helena Westerdahl, Sebastian Ernesto Ramos-Onsins, Paul J. McMurdie , Arnaud Estoup, Vincent Segura, Jacek Radwan , Torbjørn Rognes , William Stutz , Kevin Vanneste , Thomas Bigot, Jill A. Hollenbach , Wieslaw Babik , Marie-Christin... | 2019-05-15 17:30:44 | View |

20 Jan 2020

A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random ForestMarie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup https://doi.org/10.1101/671867Estimating recent divergence history: making the most of microsatellite data and Approximate Bayesian Computation approachesRecommended by Takeshi Kawakami and Concetta Burgarella based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Michael D Greenfield and 2 anonymous reviewers

The present-day distribution of extant species is the result of the interplay between their past population demography (e.g., expansion, contraction, isolation, and migration) and adaptation to the environment. Shedding light on the timing and magnitude of key demographic events helps identify potential drivers of such events and interaction of those drivers, such as life history traits and past episodes of environmental shifts. The understanding of the key factors driving species evolution gives important insights into how the species may respond to changing conditions, which can be particularly relevant for the management of harmful species, such as agricultural pests (e.g. [1]). Meaningful demographic inferences present major challenges. These include formulating evolutionary scenarios fitting species biology and the eco-geographical context and choosing informative molecular markers and accurate quantitative approaches to statistically compare multiple demographic scenarios and estimate the parameters of interest. A further issue comes with result interpretation. Accurately dating the inferred events is far from straightforward since reliable calibration points are necessary to translate the molecular estimates of the evolutionary time into absolute time units (i.e. years). This can be attempted in different ways, such as by using fossil and archaeological records, heterochronous samples (e.g. ancient DNA), and/or mutation rate estimated from independent data (e.g. [2], [3] for review). Nonetheless, most experimental systems rarely meet these conditions, hindering the comprehensive interpretation of results. The contribution of Chapuis et al. [4] addresses these issues to investigate the recent history of the African insect pest Schistocerca gregaria (desert locust). They apply Approximate Bayesian Computation-Random Forest (ABC-RF) approaches to microsatellite markers. Owing to their fast mutation rate microsatellite markers offer at least two advantages: i) suitability for analyzing recently diverged populations, and ii) direct estimate of the germline mutation rate in pedigree samples. The work of Chapuis et al. [4] benefits of both these advantages, since they have estimates of mutation rate and allele size constraints derived from germline mutations in the species [5]. The main aim of the study is to infer the history of divergence of the two subspecies of the desert locust, which have spatially disjoint distribution corresponding to the dry regions of North and West-South Africa. They first use paleo-vegetation maps to formulate hypotheses about changes in species range since the last glacial maximum. Based on them, they generate 12 divergence models. For the selection of the demographic model and parameter estimation, they apply the recently developed ABC-RF approach, a powerful inferential tool that allows optimizing the use of summary statistics information content, among other advantages [6]. Some methodological novelties are also introduced in this work, such as the computation of the error associated with the posterior parameter estimates under the best scenario. The accuracy of timing estimate is assured in two ways: i) by the use of microsatellite markers with known evolutionary dynamics, as underlined above, and ii) by assessing the divergence time threshold above which posterior estimates are likely to be biased by size homoplasy and limits in allele size range [7]. The best-supported model suggests a recent divergence event of the subspecies of S. gregaria (around 2.6 kya) and a reduction of populations size in one of the subspecies (S. g. flaviventris) that colonized the southern distribution area. As such, results did not support the hypothesis that the southward colonization was driven by the expansion of African dry environments associated with the last glacial maximum, as it has been postulated for other arid-adapted species with similar African disjoint distributions [8]. The estimated time of divergence points at a much more recent origin for the two subspecies, during the late Holocene, in a period corresponding to fairly stable arid conditions similar to current ones [9,10]. Although the authors cannot exclude that their microsatellite data bear limited information on older colonization events than the last one, they bring arguments in favour of alternative explanations. The hypothesis privileged does not involve climatic drivers, but the particularly efficient dispersal behaviour of the species, whose individuals are able to fly over long distances (up to thousands of kilometers) under favourable windy conditions. A single long-distance dispersal event by a few individuals would explain the genetic signature of the bottleneck. There is a growing number of studies in phylogeography in arid regions in the Southern hemisphere, but the impact of past climate changes on the species distribution in this region remains understudied relative to the Northern hemisphere [11,12]. The study presented by Chapuis et al. [4] offers several important insights into demographic changes and the evolutionary history of an agriculturally important pest species in Africa, which could also mirror the history of other organisms in the continent. As the authors point out, there are necessarily some uncertainties associated with the models of past ecosystems and climate, especially for Africa. Interestingly, the authors argue that the information on paleo-vegetation turnover was more informative than climatic niche modeling for the purpose of their study since it made them consider a wider range of bio-geographical changes and in turn a wider range of evolutionary scenarios (see discussion in Supplementary Material). Microsatellite markers have been offering a useful tool in population genetics and phylogeography for decades, but their popularity is perhaps being taken over by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (the peak year of the number of the publication with “microsatellite” is in 2012 according to PubMed). This study reaffirms the usefulness of these classic molecular markers to estimate past demographic events, especially when species- and locus-specific microsatellite mutation features are available and a powerful inferential approach is adopted. Nonetheless, there are still hurdles to overcome, such as the limitations in scenario choice associated with the simulation software used (e.g. not allowing for continuous gene flow in this particular case), which calls for further improvement of simulation tools allowing for more flexible modeling of demographic events and mutation patterns. In sum, this work not only contributes to our understanding of the makeup of the African biodiversity but also offers a useful statistical framework, which can be applied to a wide array of species and molecular markers (microsatellites, SNPs, and WGS). References [1] Lehmann, P. et al. (2018). Complex responses of global insect pests to climate change. bioRxiv, 425488. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/425488 [2] Donoghue, P. C., & Benton, M. J. (2007). Rocks and clocks: calibrating the Tree of Life using fossils and molecules. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(8), 424-431. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.05.005 [3] Ho, S. Y., Lanfear, R., Bromham, L., Phillips, M. J., Soubrier, J., Rodrigo, A. G., & Cooper, A. (2011). Time‐dependent rates of molecular evolution. Molecular ecology, 20(15), 3087-3101. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05178.x [4] Chapuis, M.-P., Raynal, L., Plantamp, C., Meynard, C. N., Blondin, L., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020). A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest. bioRxiv, 671867, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/671867 5] Chapuis, M.-P., Plantamp, C., Streiff, R., Blondin, L., & Piou, C. (2015). Microsatellite evolutionary rate and pattern in Schistocerca gregaria inferred from direct observation of germline mutations. Molecular ecology, 24(24), 6107-6119. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mec.13465 [6] Raynal, L., Marin, J. M., Pudlo, P., Ribatet, M., Robert, C. P., & Estoup, A. (2018). ABC random forests for Bayesian parameter inference. Bioinformatics, 35(10), 1720-1728. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty867 [7] Estoup, A., Jarne, P., & Cornuet, J. M. (2002). Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Molecular ecology, 11(9), 1591-1604. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01576.x [8] Moodley, Y. et al. (2018). Contrasting evolutionary history, anthropogenic declines and genetic contact in the northern and southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1890), 20181567. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1567 [9] Kröpelin, S. et al. (2008). Climate-driven ecosystem succession in the Sahara: the past 6000 years. science, 320(5877), 765-768. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1154913 [10] Maley, J. et al. (2018). Late Holocene forest contraction and fragmentation in central Africa. Quaternary Research, 89(1), 43-59. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.97 [11] Beheregaray, L. B. (2008). Twenty years of phylogeography: the state of the field and the challenges for the Southern Hemisphere. Molecular Ecology, 17(17), 3754-3774. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03857.x [12] Dubey, S., & Shine, R. (2012). Are reptile and amphibian species younger in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere?. Journal of evolutionary biology, 25(1), 220-226. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02417.x ***** A video about this preprint is available here: | A young age of subspecific divergence in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria, inferred by ABC Random Forest | Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Louis Raynal, Christophe Plantamp, Christine N. Meynard, Laurence Blondin, Jean-Michel Marin, Arnaud Estoup | <p>Dating population divergence within species from molecular data and relating such dating to climatic and biogeographic changes is not trivial. Yet it can help formulating evolutionary hypotheses regarding local adaptation and future responses t... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Takeshi Kawakami | 2019-06-20 10:31:15 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shiftsGilles Didier https://doi.org/10.1101/376756Fitting diversification models on undated or partially dated treesRecommended by Nicolas Lartillot based on reviews by Amaury Lambert, Dominik Schrempf and 1 anonymous reviewerPhylogenetic trees can be used to extract information about the process of diversification that has generated them. The most common approach to conduct this inference is to rely on a likelihood, defined here as the probability of generating a dated tree T given a diversification model (e.g. a birth-death model), and then use standard maximum likelihood. This idea has been explored extensively in the context of the so-called diversification studies, with many variants for the models and for the questions being asked (diversification rates shifting at certain time points or in the ancestors of particular subclades, trait-dependent diversification rates, etc). References [1] Didier, G. (2020) Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts. bioRxiv, 376756, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/376756 | Probabilities of tree topologies with temporal constraints and diversification shifts | Gilles Didier | <p>Dating the tree of life is a task far more complicated than only determining the evolutionary relationships between species. It is therefore of interest to develop approaches apt to deal with undated phylogenetic trees. The main result of this ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Macroevolution | Nicolas Lartillot | 2019-01-30 11:28:58 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snailsPilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pereira, Luiggi Martini Robles, Richar Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Nelson Uribe, Patrice David, Philippe Jarne, Jean-Pierre Pointier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès https://doi.org/10.1101/647867The challenge of delineating species when they are hiddenRecommended by Fabien Condamine based on reviews by Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse and Niklas WahlbergThe science of naming species (taxonomy) has been renewed with the developments of molecular sequencing, digitization of museum specimens, and novel analytical tools. However, naming species can be highly subjective, sometimes considered as an art [1], because it is based on human-based criteria that vary among taxonomists. Nonetheless, taxonomists often argue that species names are hypotheses, which are therefore testable and refutable as new evidence is provided. This challenge comes with a more and more recognized and critical need for rigorously delineated species not only for producing accurate species inventories, but more importantly many questions in evolutionary biology (e.g. speciation), ecology (e.g. ecosystem structure and functioning), conservation biology (e.g. targeting priorities) or biogeography (e.g. diversification processes) depend in part on those species inventories and our knowledge of species [2-3]. Inaccurate species boundaries or diversity estimates may lead us to deliver biased answers to those questions, exactly as phylogenetic trees must be reconstructed rigorously and analyzed critically because they are a first step toward discussing broader questions [2-3]. In this context, biological diversity needs to be studied from multiple and complementary perspectives requiring the collaboration of morphologists, molecular biologists, biogeographers, and modelers [4-5]. Integrative taxonomy has been proposed as a solution to tackle the challenge of delimiting species [2], especially in highly diverse and undocumented groups of organisms. References [1] Ohl, M. (2018). The art of naming. MIT Press. | Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails | Pilar Alda, Manon Lounnas, Antonio Alejandro Vázquez, Rolando Ayaqui, Manuel Calvopina, Maritza Celi-Erazo, Robert Dillon, Luisa Carolina González Ramírez, Eric S. Loker, Jenny Muzzio-Aroca, Alberto Orlando Nárvaez, Oscar Noya, Andrés Esteban Pere... | <p>Cryptic species can present a significant challenge to the application of systematic and biogeographic principles, especially if they are invasive or transmit parasites or pathogens. Detecting cryptic species requires a pluralistic approach in ... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Systematics / Taxonomy | Fabien Condamine | Pavel Matos, Christelle Fraïsse | 2019-05-25 10:34:57 | View |

09 Dec 2019

Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasitesEva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand https://doi.org/10.1101/621581Trade-offs in fitness components and ecological source-sink dynamics affect host specialisation in two parasites of Artemia shrimpsRecommended by Frédéric Guillaume based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin based on reviews by Anne Duplouy, Seth Barribeau and Cindy Gidoin

Ecological specialisation, especially among parasites infecting a set of host species, is ubiquitous in nature. Host specialisation can be understood as resulting from trade-offs in parasite infectivity, virulence and growth. However, it is not well understood how variation in these trade-offs shapes the overall fitness trade-off a parasite faces when adapting to multiple hosts. For instance, it is not clear whether a strong trade-off in one fitness component may sufficiently constrain the evolution of a generalist parasite despite weak trade-offs in other components. A second mechanism explaining variation in specialisation among species is habitat availability and quality. Rare habitats or habitats that act as ecological sinks will not allow a species to persist and adapt, preventing a generalist phenotype to evolve. Understanding the prevalence of those mechanisms in natural systems is crucial to understand the emergence and maintenance of host specialisation, and biodiversity in general. In their study "Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites", Lievens *et al.* [1] report the results of an evolution experiment involving two parasitic microsporidians, *Anostracospora rigaudi* and *Enterocytospora artemiae*, infecting two sympatric species of brine shrimp, *Artemia franciscana* and *Artemia parthenogenetica*. The two parasites were originally specialised on their primary host: *A. rigaudi* on *A. parthenogenetica* and *E. artemiae* on *A. franciscana*, although they encounter both species in the wild but at different rates. After passaging each parasite on each single host and on both hosts alternatively, Lievens *et al.* asked how host specialisation evolved. They found no change in specialisation at the fitness level in *A. rigaudi* in either treatment, while *E. artemiae* became more of a generalist after having been exposed to its secondary host, *A. parthenogenetica*. The most interesting part of the study is the decomposition of the fitness trade-off into its underlying trade-offs in spore production, infectivity and virulence. Both species remained specialised for spore production on their primary host, interpreted as caused by a strong trade-off between hosts preventing improvements on the secondary host. *A. rigaudi* evolved reduced virulence on its primary host without changes in the overall fitness trad-off, while *E. artemiae* evolved higher infectivity on its secondary host making it a more generalist parasite and revealing a weak trade-off for this trait and for fitness. Nevertheless, both parasites retained higher fitness on their primary host because of the lack of an evolutionary response in spore production. This study made two important points. First, it showed that despite apparent strong trade-off in spore production, a weak trade-off in infectivity allowed *E. artemiae* to become less specialised. In contrast, *A. rigaudi* remained specialised, presumably because the strong trade-off in spore production was the overriding factor. The fitness trade-off that results from the superposition of multiple underlying trade-offs is thus difficult to predict, yet crucial to understand potential evolutionary outcomes. A second insight is related to the ecological context of the evolution of specialisation. The results showed that *E. artemiae* should be less specialised than observed, which points to a role played by source-sink dynamics on *A. parthenogenetica* in the wild. The experimental approach of Lievens *et al.* thus allowed them to nicely disentangle the various sources of constraints on the evolution of host adaptation in the *Artemia* system. **References** [1] Lievens, E.J.P., Michalakis, Y. and Lenormand, T. (2019). Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites. bioRxiv, 621581, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: [10.1101/621581](https://dx.doi.org/10.1101/621581) | Trait-specific trade-offs prevent niche expansion in two parasites | Eva JP Lievens, Yannis Michalakis, Thomas Lenormand | <p>The evolution of host specialization has been studied intensively, yet it is still often difficult to determine why parasites do not evolve broader niches – in particular when the available hosts are closely related and ecologically similar. He... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Experimental Evolution, Life History, Species interactions | Frédéric Guillaume | 2019-05-13 13:44:34 | View | |

26 Nov 2019

Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studiesJobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume https://doi.org/10.1101/656413Understanding the effects of linkage and pleiotropy on evolutionary adaptationRecommended by Kathleen Lotterhos based on reviews by Pär Ingvarsson and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic correlations among traits are ubiquitous in nature. However, we still have a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of trait correlations. Some genetic correlations among traits arise because of pleiotropy - single mutations or genotypes that have effects on multiple traits. Other genetic correlations among traits arise because of linkage among mutations that have independent effects on different traits. Teasing apart the differential effects of pleiotropy and linkage on trait correlations is difficult, because they result in very similar genetic patterns. However, understanding these differential effects gives important insights into how ubiquitous pleiotropy may be in nature. References [1] Chebib, J. and Guillaume, F. (2019). Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies. bioRxiv, 656413, v3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Evolutionary Biology. doi: 10.1101/656413 | Pleiotropy or linkage? Their relative contributions to the genetic correlation of quantitative traits and detection by multi-trait GWA studies | Jobran Chebib and Frédéric Guillaume | <p>Genetic correlations between traits may cause correlated responses to selection depending on the source of those genetic dependencies. Previous models described the conditions under which genetic correlations were expected to be maintained. Sel... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Genotype-Phenotype, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics | Kathleen Lotterhos | 2019-06-05 13:51:43 | View | |

21 Nov 2019

Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticityRobin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous https://doi.org/10.1101/717702Nutrition-dependent effects of gut bacteria on growth plasticity in Drosophila melanogasterRecommended by Wolf Blanckenhorn based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewerIt is well known that the rearing environment has strong effects on life history and fitness traits of organisms. Microbes are part of every environment and as such likely contribute to such environmental effects. Gut bacteria are a special type of microbe that most animals harbor, and as such they are part of most animals’ environment. Such microbial symbionts therefore likely contribute to local adaptation [1]. The main question underlying the laboratory study by Guilhot et al. [2] was: How much do particular gut bacteria affect the organismal phenotype, in terms of life history and larval foraging traits, of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, a common laboratory model species in biology? References [1] Kawecki, T. J. and Ebert, D. (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7: 1225-1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x | Environmental specificity in Drosophila-bacteria symbiosis affects host developmental plasticity | Robin Guilhot, Antoine Rombaut, Anne Xuéreb, Kate Howell, Simon Fellous | <p>Environmentally acquired microbial symbionts could contribute to host adaptation to local conditions like vertically transmitted symbionts do. This scenario necessitates symbionts to have different effects in different environments. We investig... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Phenotypic Plasticity, Species interactions | Wolf Blanckenhorn | 2019-02-13 15:22:23 | View | |

20 Nov 2019

Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communicationHugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan L. Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez https://doi.org/10.1101/586362Feathers iridescence sheds light on the assembly rules of humingbirds communitiesRecommended by Sébastien Lavergne based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersEcology needs rules stipulating how species distributions and ecological communities should be assembled along environmental gradients, but few rules have yet emerged in the ecological literature. The search of ecogeographical rules governing the spatial variation of birds colours has recently known an upsurge of interest in the litterature [1]. Most studies have, however, looked at pigmentary colours and not structural colours (e.g. iridescence), although it is know that color perception by animals (both birds and their predators) can be strongly influenced by light diffraction causing iridescence patterns on feathers. References [1] Delhey, K. (2019). A review of Gloger’s rule, an ecogeographical rule of colour: definitions, interpretations and evidence. Biological Reviews, 94(4), 1294–1316. doi: 10.1111/brv.12503 | Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication | Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan L. Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez | <p>Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification am... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Macroevolution, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Sexual Selection, Species interactions | Sébastien Lavergne | 2019-03-29 17:23:20 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang