Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Oct 2021

Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North AfricaOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tournant L., Gazel F., Mody K., Khachtib Y., Roman A., Ursu T.M., Zakharov I.A., Belcram H., Harry M., Roth M., Simon J.C., Oram S., Ricard J.M., Agnello A., Beers E. H., Engelman J., Balti I., Salhi-Hannachi A., Zhang H., Tu H., Mottet C., Barrès B., Degra... https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644The evolutionary puzzle of the host-parasite-endosymbiont Russian doll for apples and aphidsRecommended by Ignacio Bravo based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Simões and 1 anonymous reviewer

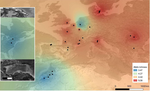

Each individual multicellular organism, each of our bodies, is a small universe. Every living surface -skin, cuticle, bark, mucosa- is the home place to milliards of bacteria, fungi and viruses. They constitute our microbiota. Some of them are essential for certain organisms. Other could not live without their hosts. For many species, the relationship between host and microbiota is so close that their histories are inseparable. The recognition of this biological inextricability has led to the notion of holobiont as the organism ensemble of host and microbiota. When individuals of a particular animal or plant species expand their geographical range, it is the holobiont that expands. And these processes of migration, expansion and colonization are often accompanied by evolutionary and ecological innovations in the interspecies relationships, at the macroscopic level (e.g. novel predator-prey or host-parasite interactions) and at the microscopic level (e.g. changes in the microbiota composition). From the human point of view, these novel interactions can be economically disastrous if they involve and threaten important crop or cattle species. And this is especially worrying in the present context of genetic standardization and intensification for mass-production on the one hand, and of climate change on the other. With this perspective, the international team led by Amandine Cornille presents a study aiming at understanding the evolutionary history of the rosy apple aphid Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, a major pest of the cultivated apple tree Malus domestica Borkh (1). The apple tree was probably domesticated in Central Asia, and later disseminated by humans over the world in different waves, and it was probably introduced in Europe by the Greeks. It is however unclear when and where D. plantaginea started parasitizing the cultivated apple tree. The ancestral D. plantaginea could have already infected the wild ancestor of current cultivated apple trees, but the aphid is not common in Central Asia. Alternatively, it may have gained access only later to the plant, possibly via a host jump, from Pyrus to Malus that may have occurred in Asia Minor or in the Caucasus. In the present preprint, Olvera-Vázquez and coworkers have analysed over 650 D. plantaginea colonies from 52 orchards in 13 countries, in Western, Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Morocco and the USA. The authors have analysed the genetic diversity in the sampled aphids, and have characterized as well the composition of the associated endosymbiont bacteria. The analyses detect substantial recent admixture, but allow to identify aphid subpopulations slightly but significantly differentiated and isolated by distance, especially those in Morocco and the USA, as well as to determine the presence of significant gene flow. This process of colonization associated to gene flow is most likely indirectly driven by human interactions. Very interestingly, the data show that this genetic diversity in the aphids is not reflected by a corresponding diversity in the associated microbiota, largely dominated by a few Buchnera aphidicola variants. In order to determine polarity in the evolutionary history of the aphid-tree association, the authors have applied approximate Bayesian computing and machine learning approaches. Albeit promising, the results are not sufficiently robust to assess directionality nor to confidently assess the origin of the crop pest. Despite the large effort here communicated, the authors point to the lack of sufficient data (in terms of aphid isolates), especially originating from Central Asia. Such increased sampling will need to be implemented in the future in order to elucidate not only the origin and the demographic history of the interaction between the cultivated apple tree and the rosy apple aphid. This knowledge is needed to understand how this crop pest struggles with the different seasonal and geographical selection pressures while maintaining high genetic diversity, conspicuous gene flow, differentiated populations and low endosymbiontic diversity. References

| Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Remoué C., Venon A, Rousselet A., Grandcolas O., Azrine M., Momont L., Galan M., Benoit L., David G., Alhmedi A., Beliën T., Alins G., Franck P., Haddioui A., Jacobsen S.K., Andreev R., Simon S., Sigsgaard L., Guibert E., Tour... | <p style="text-align: justify;">With frequent host shifts involving the colonization of new hosts across large geographical ranges, crop pests are good models for examining the mechanisms of rapid colonization. The microbial partners of pest insec... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics, Species interactions | Ignacio Bravo | 2020-12-11 19:22:54 | View | |

11 Oct 2021

Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansionsMaxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752Phenotypic evolution during range expansions is contingent on connectivity and density dependenceRecommended by Inês Fragata based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the mechanisms underlying range expansions is key for predicting species distributions in response to environmental changes (such as global warming) and managing the global expansion of invasive species (Parmesan 2006; Suarez & Tsutsui 2008). Traditionally, two types of ecological processes were studied as essential in shaping range expansion: dispersal and population growth. However, ecology and evolution are intertwined in range expansions, as phenotypic evolution of traits involved in demographic and dispersal patterns and processes can affect and be affected by ecological dynamics, representing a full eco-evolutionary loop (Williams et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). Range expansions can be characterized by the type of population growth and dispersal, divided into pushed or pulled range expansions. Species that have high dispersal and high population growth at low densities present pulled range expansions (pulled by individuals from the edge populations). In contrast, populations presenting increased growth rate at intermediate densities (due to Allee effects - Allee & Bowen 1932; i.e. where growth rate decreases at lower densities) and high dispersal at high densities present pushed range expansions (driven by individuals from core and intermediate populations) (Gandhi et al. 2016). Importantly, the type of expansion is expected to have very different consequences on the genetic (and therefore) phenotypic composition of core and edge populations. Specifically, genetic variability is expected to be lower in populations experiencing pulled expansions and higher in populations involved in pushed expansions (Gandhi et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2020). However, it is not always possible to distinguish between pulled and pushed expansions, as variation in speed and shape can overlap between the two types. In addition, it is difficult to experimentally manipulate the strength of the Allee effect to create pushed versus pulled expansions. Thus, several critical predictions regarding the genetic and phenotypic composition of pulled and pushed expansions are lacking empirical tests (but see Gandhi et al. 2016). In a previous study, Dahirel et al. (2021a) combined simulations and experimental evolution of the small wasps Trichogramma brassicae to show that low connectivity led to more pushed expansions, and higher connectivity generated more pulled expansions. In accordance with theoretical predictions, this led to reduced genetic diversity in pulled expansions, and the reverse pattern in pushed expansions. However, the question of how pulled and pushed expansions affect trait evolution remained unanswered. In this follow-up study, Dahirel et al. (2021b) tackled this issue and linked the changes in connectivity and type of expansion with the phenotypic evolution of several traits using individuals from their previous experiment. Namely, the authors compared core and edge populations with founder strains to test how evolution in pushed vs. pulled expansions affected wasp size, short movement, fecundity, dispersal, and density dependent dispersal. When density dependence was not accounted for, phenotypic changes in edge populations did not match the expectations from changes in expansion dynamics. This could be due to genetic trade-offs between traits that limit phenotypic evolution (Urquhart & Williams 2021). However, when accounting for density dependent dispersal, Dahirel et al. (2021b) observed that more connected landscapes (with pulled expansions) showed positive density dispersal in core populations and negative density dispersal in edge populations, similarly to other studies (e.g. Fronhofer et al. 2017). Interestingly, in pushed (with lower connectivity) landscapes, such shift was not observed. Instead, edge populations maintained positive density dispersal even after 14 generations of expansion, whereas core populations showed higher dispersal at lower density. The authors suggest that this seemingly contradictory result is due to a combination of three processes: 1) the expansion reduced positive density dispersal in edge populations; 2) reduced connectivity directly increased dispersal costs, increasing high density dispersal; and 3) reduced connectivity indirectly caused demographic stochasticity (and reduced temporal variability in patches) leading to higher dispersal at low density in core populations. However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt, since only one of the four experimental replicates were used in the density dependent dispersal experiment. In range expansions experiments, replication is fundamental, since stochastic processes (such as gene surfing, where alleles maybe rise in frequency due by chance) are prevalent (Miller et al. 2020), and results are highly dependent on sample size, or number of replicate populations analysed. Having said that, results from Dahirel et al. (2021b) highlight the importance to contextualize the management of invasions and species distribution, since it is thought that pulled expansions are more prevalent in nature, but pushed expansions can be more important in scenarios where patchiness is high, such as urban landscapes. Moreover, Dahirel's et al. (2021b) study is a first step showing that accounting for trait density dependence is crucial when following phenotypic evolution during range expansion, and that evolution of density dependent traits may be constrained by landscape conditions. This highlights the need to account for both connectivity and density dependence to draw more accurate predictions on the evolutionary and ecological outcomes of range expansions. Allee WC, Bowen ES (1932) Studies in animal aggregations: Mass protection against colloidal silver among goldfishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 61, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400610202 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Calcagno V, Duraj C, Fellous S, Groussier G, Lombaert E, Mailleret L, Marchand A, Vercken E (2021a) Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433752, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433752 Dahirel M, Bertin A, Haond M, Blin A, Lombaert E, Calcagno V, Fellous S, Mailleret L, Malausa T, Vercken E (2021b) Shifts from pulled to pushed range expansions caused by reduction of landscape connectivity. Oikos, 130, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08278 Fronhofer EA, Gut S, Altermatt F (2017) Evolution of density-dependent movement during experimental range expansions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 30, 2165–2176. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13182 Gandhi SR, Yurtsev EA, Korolev KS, Gore J (2016) Range expansions transition from pulled to pushed waves as growth becomes more cooperative in an experimental microbial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 6922–6927. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521056113 Miller TEX, Angert AL, Brown CD, Lee-Yaw JA, Lewis M, Lutscher F, Marculis NG, Melbourne BA, Shaw AK, Szűcs M, Tabares O, Usui T, Weiss-Lehman C, Williams JL (2020) Eco-evolutionary dynamics of range expansion. Ecology, 101, e03139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3139 Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND (2008) The evolutionary consequences of biological invasions. Molecular Ecology, 17, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03456.x Urquhart CA, Williams JL (2021) Trait correlations and landscape fragmentation jointly alter expansion speed via evolution at the leading edge in simulated range expansions. Theoretical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-021-00503-z Williams JL, Hufbauer RA, Miller TEX (2019) How Evolution Modifies the Variability of Range Expansion. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.05.012 | Landscape connectivity alters the evolution of density-dependent dispersal during pushed range expansions | Maxime Dahirel, Aline Bertin, Vincent Calcagno, Camille Duraj, Simon Fellous, Géraldine Groussier, Eric Lombaert, Ludovic Mailleret, Anaël Marchand, Elodie Vercken | <p style="text-align: justify;">As human influence reshapes communities worldwide, many species expand or shift their ranges as a result, with extensive consequences across levels of biological organization. Range expansions can be ranked on a con... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Experimental Evolution | Inês Fragata | 2021-03-05 17:15:46 | View | |

01 Sep 2021

Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail speciesJarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242Determinants of population genetic structure in co-occurring freshwater snailsRecommended by Trine Bilde and Matteo Fumagalli and Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Genetic diversity is a key aspect of biodiversity and has important implications for evolutionary potential and thereby the persistence of species. Improving our understanding of the factors that drive genetic structure within and between populations is, therefore, a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology. However, this is a major challenge, because of the complex interplay between genetic drift, migration, and extinction/colonization dynamics on the one hand, and the biology and ecology of species on the other hand (Romiguier et al. 2014, Ellegren and Galtier 2016, Charlesworth 2003). Jarne et al. (2021) studied whether environmental and demographic factors affect the population genetic structure of four species of hermaphroditic freshwater snails in a similar way, using comparative analyses of neutral genetic microsatellite markers. Specifically, they investigated microsatellite variability of Hygrophila in almost 280 sites in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles, as part of a long-term survey experiment (Lamy et al. 2013). They then modelled the influence of the mating system, local environmental characteristics and demographic factors on population genetic diversity. Consistent with theoretical predictions (Charlesworth 2003), they detected higher genetic variation in two outcrossing species than in two selfing species, emphasizing the importance of the mating system in maintaining genetic diversity. The study further identified an important role of site connectivity, through its influences on effective population size and extinction/colonisation events. Finally, the study detects an influence of interspecific interactions caused by an ongoing invasion by one of the studied species on genetic structure, highlighting the indirect effect of changes in community composition and demography on population genetics. Jarne et al. (2021) could address the extent to which genetic structure is determined by demographic and environmental factors in multiple species given the remarkable sampling available. Additionally, the study system is extremely suitable to address this hypothesis as species’ habitats are defined and delineated. Whilst the authors did attempt to test for across-species correlations, further investigations on this matter are required. Moreover, the effect of interactions between factors should be appropriately considered in any modelling between genetic structure and local environmental or demographic features. The findings in this study contribute to improving our understanding of factors influencing population genetic diversity, and highlights the complexity of interacting factors, therefore also emphasizing the challenges of drawing general implications, additionally hampered by the relatively limited number of species studied. Jarne et al. (2021) provide an excellent showcase of an empirical framework to test determinants of genetic structure in natural populations. As such, this study can be an example for further attempts of comparative analysis of genetic diversity. References Charlesworth, D. (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358, 1051-1070. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1296 Ellegren, H. and Galtier, N. (2016) Determinants of genetic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17, 422-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.58 Jarne, P., Lozano del Campo, A., Lamy, T., Chapuis, E., Dubart, M., Segard, A., Canard, E., Pointier, J.-P. and David, P. (2021) Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species. HAL, hal-03295242, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03295242 Lamy, T., Gimenez, O., Pointier, J. P., Jarne, P. and David, P. (2013). Metapopulation dynamics of species with cryptic life stages. The American Naturalist, 181, 479-491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/669676 Romiguier, J., Gayral, P., Ballenghien, M. et al. (2014) Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature, 515, 261-263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13685 | Connectivity and selfing drives population genetic structure in a patchy landscape: a comparative approach of four co-occurring freshwater snail species | Jarne P., Lozano del Campo A., Lamy T., Chapuis E., Dubart M., Segard A., Canard E., Pointier J.-P., David P. | <p style="text-align: justify;">The distribution of neutral genetic variation in subdivided populations is driven by the interplay between genetic drift, migration, local extinction and colonization. The influence of environmental and demographic ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Dynamics, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex, Species interactions | Trine Bilde | 2021-02-11 19:57:51 | View | ||

30 Aug 2021

The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactionsMoury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Juliette, Fabre Frédéric, Fournet Sylvain, Grimault Valérie, Jaunet Thierry, Justafré Isabelle, Lefebvre Véronique, Losdat Denis, Marcel Thierry C., Montarry Josselin, Morris Cindy E., Omrani Mariem, Paineau Manon, Perrot Sophie, Pilet-Nayel Marie-Laure, R... https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745Nestedness and modularity in plant-parasite infection networksRecommended by Santiago Elena based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rubén González and 2 anonymous reviewers

In a landmark paper, Flores et al. (2011) showed that the interactions between bacteria and their viruses could be nicely described using a bipartite infection networks. Two quantitative properties of these networks were of particular interest, namely modularity and nestedness. Modularity emerges when groups of host species (or genotypes) shared groups of viruses. Nestedness provided a view of the degree of specialization of both partners: high nestedness suggests that hosts differ in their susceptibility to infection, with some highly susceptible host genotypes selecting for very specialized viruses while strongly resistant host genotypes select for generalist viruses. Translated to the plant pathology parlance, this extreme case would be equivalent to a gene-for-gene infection model (Flor 1956): new mutations confer hosts with resistance to recently evolved viruses while maintaining resistance to past viruses. Likewise, virus mutations for expanding host range evolve without losing the ability to infect ancestral host genotypes. By contrast, a non-nested network would represent a matching-allele infection model (Frank 2000) in which each interacting organism evolves by losing its capacity to resist/infect its ancestral partners, resembling a Red Queen dynamic. Obviously, the reality is more complex and may lie anywhere between these two extreme situations. Recently, Valverde et al. (2020) developed a model to explain the emergence of nestedness and modularity in plant-virus infection networks across diverse habitats. They found that local modularity could coexist with global nestedness and that intraspecific competition was the main driver of the evolution of ecosystems in a continuum between nested-modular and nested networks. These predictions were tested with field data showing the association between plant host species and different viruses in different agroecosystems (Valverde et al. 2020). The effect of interspecific competition in the structure of empirical plant host-virus infection networks was also tested by McLeish et al. (2019). Besides data from agroecosystems, evolution experiments have also shown the pervasive emergence of nestedness during the diversification of independently-evolved lineages of potyviruses in Arabidopsis thaliana genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection (Hillung et al. 2014; González et al. 2019; Navarro et al. 2020). In their study, Moury et al. (2021) have expanded all these previous observations to a diverse set of pathosystems that range from viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes to insects. While modularity was barely seen in only a few of the systems, nestedness was a common trend (observed in ~94% of all systems). This nestedness, as seen in previous studies and as predicted by theory, emerged as a consequence of the existence of generalist and specialist strains of the parasites that differed in their capacity to infect more or less resistant plant genotypes. As pointed out by Moury et al. (2021) in their conclusions, the ubiquity of nestedness in plant-parasite infection matrices has strong implications for the evolution and management of infectious diseases. References Flor, H. H. (1956). The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics, 8, 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8 Flores, C. O., Meyer, J. R., Valverde, S., Farr, L., and Weitz, J. S. (2011). Statistical structure of host–phage interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, E288-E297. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101595108 Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 202, 283-304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054 González, R., Butković, A., and Elena, S. F. (2019). Role of host genetic diversity for susceptibility-to-infection in the evolution of virulence of a plant virus. Virus evolution, 5(2), vez024. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez052 Hillung, J., Cuevas, J. M., Valverde, S., and Elena, S. F. (2014). Experimental evolution of an emerging plant virus in host genotypes that differ in their susceptibility to infection. Evolution, 68, 2467-2480. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12458 McLeish, M., Sacristán, S., Fraile, A., and García-Arenal, F. (2019). Coinfection organizes epidemiological networks of viruses and hosts and reveals hubs of transmission. Phytopathology, 109, 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0293-R Moury B, Audergon J-M, Baudracco-Arnas S, Krima SB, Bertrand F, Boissot N, Buisson M, Caffier V, Cantet M, Chanéac S, Constant C, Delmotte F, Dogimont C, Doumayrou J, Fabre F, Fournet S, Grimault V, Jaunet T, Justafré I, Lefebvre V, Losdat D, Marcel TC, Montarry J, Morris CE, Omrani M, Paineau M, Perrot S, Pilet-Nayel M-L and Ruellan Y (2021) The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions. bioRxiv, 2021.03.03.433745, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.03.433745 Navarro, R., Ambros, S., Martinez, F., Wu, B., Carrasco, J. L., and Elena, S. F. (2020). Defects in plant immunity modulate the rates and patterns of RNA virus evolution. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.13.337402 Valverde, S., Vidiella, B., Montañez, R., Fraile, A., Sacristán, S., and García-Arenal, F. (2020). Coexistence of nestedness and modularity in host–pathogen infection networks. Nature ecology & evolution, 4, 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1130-9 | The quasi-universality of nestedness in the structure of quantitative plant-parasite interactions | Moury Benoît, Audergon Jean-Marc, Baudracco-Arnas Sylvie, Ben Krima Safa, Bertrand François, Boissot Nathalie, Buisson Mireille, Caffier Valérie, Cantet Mélissa, Chanéac Sylvia, Constant Carole, Delmotte François, Dogimont Catherine, Doumayrou Jul... | <p>Understanding the relationships between host range and pathogenicity for parasites, and between the efficiency and scope of immunity for hosts are essential to implement efficient disease control strategies. In the case of plant parasites, most... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Species interactions | Santiago Elena | 2021-03-04 21:23:08 | View | |

26 Aug 2021

Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durabilityMéline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112Durability of plant resistance to diploid pathogenRecommended by Hirohisa Kishino based on reviews by Loup Rimbaud and 1 anonymous reviewerDurability of plant resistance to diploid pathogen Hirohisa Kishino Based on the population genetic and epidemiologic model, Saubin et al. (2021) report that the resistant hosts generated by the breeding based on the gene-for-gene interaction is durable much longer against diploid pathogens than haploid pathogens. The avr allele of pathogen that confers the resistance is genetically recessive. The heterozygotes are not recognized by the resistant hosts and only the avr/avr homozygote is adaptive. As a result, the trajectory of avr allele frequency becomes more stochastic due to genetic drift. Although the paper focuses on the evolution of standing polymorphism, it seems obvious that the adaptive mutations in pathogen have much larger probability of being deleted from the population because the individuals own the avr allele mostly in the form of heterozygote at the initial phase after the mutation. Since only few among many models of plant resistance deployment study the case of diploid pathogen and the contribution of the pathogen life cycle, this work will add an important intellect to the literature (Rimbaud et al. 2021). From the study of host-parasite interaction in flax rust Melampsora lini, Flor (1942, 1955) showed that the host resistance is formed by the interaction of a host resistance gene and a corresponding pathogen gene. This gene-for-gene hypothesis has been supported by experimental evidence and has served as a basis of the methods of molecular breeding targeting the dominant R genes. However, modern agriculture provides the pathogen populations with the homogeneous environments and laid strong selection pressure on them. As a result, the newly developed resistant plants face the risk of immediate resistance breakdown (Möller and Stukenbrock 2017). Currently, quantitative resistance is getting attention as characters as a potential target for long-life (mild) resistant breeds (Lannou, 2012). They are polygenic and controlled partly by the same genes that mediate qualitative resistance but mostly by the genes that encode defense-related outputs such as strengthening of the cell wall or defense compound biosynthesis (Corwin and Kliebenstein, 2017). Progress of molecular genetics may overcome the technical difficulty (Bakkeren and Szabo, 2020). Saubin et al. (2021) notes that the pattern of genetic inheritance of the pathogen counterparts that respond to the host traits is crucial regarding with the durability of the resistant hosts. The resistance traits for which avr alleles are predicted to be recessive may be the targets of breeding. References Bakkeren, G., and Szabo, L. J. (2020) Progress on molecular genetics and manipulation of rust fungi. Phytopathology, 110, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-19-0228-IA Corwin, J. A., and Kliebenstein, D. J. (2017) Quantitative resistance: more than just perception of a pathogen. The Plant Cell, 29, 655-665. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00915 Flor, H. H. (1942) Inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiological races 22 and 24 of Melampsova lini. Phytopathology, 35. Abstract. Flor, H. H. (1955) Host-parasite interactions in flax rust-its genetics and other implications. Phytopathology, 45, 680-685. Lannou, C. (2012) Variation and selection of quantitative traits in plant pathogens. Annual review of phytopathology, 50, 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173031 Möller, M. and Stukenbrock, E. H. (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.76 Rimbaud, L., Fabre, F., Papaïx, J., Moury, B., Lannou, C., Barrett, L. G., and Thrall, P. H. (2021) Models of Plant Resistance Deployment. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-122134 Saubin, M., De Mita, S., Zhu, X., Sudret, B. and Halkett, F. (2021) Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability. bioRxiv, 2021.05.28.446112, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.28.446112 | Impact of ploidy and pathogen life cycle on resistance durability | Méline Saubin, Stephane De Mita, Xujia Zhu, Bruno Sudret, Fabien Halkett | <p>The breeding of resistant hosts based on the gene-for-gene interaction is crucial to address epidemics of plant pathogens in agroecosystems. Resistant host deployment strategies are developed and studied worldwide to decrease the probability of... |  | Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Epidemiology | Hirohisa Kishino | 2021-06-03 07:58:16 | View | |

19 Jul 2021

Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasitesHannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259Modelling parasitoid virulence evolution with seasonalityRecommended by Samuel Alizon based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Alex Best and 2 anonymous reviewers

The harm most parasites cause to their host, i.e. the virulence, is a mystery because host death often means the end of the infectious period. For obligate killer parasites, or “parasitoids”, that need to kill their host to transmit to other hosts the question is reversed. Indeed, more rapid host death means shorter generation intervals between two infections and mathematical models show that, in the simplest settings, natural selection should always favour more virulent strains (Levin and Lenski, 1983). Adding biological details to the model modifies this conclusion and, for instance, if the relationship between the infection duration and the number of parasites transmission stages produced in a host is non-linear, strains with intermediate levels of virulence can be favoured (Ebert and Weisser 1997). Other effects, such as spatial structure, could yield similar effects (Lion and van Baalen, 2007). In their study, MacDonald et al. (2021) explore another type of constraint, which is seasonality. Earlier studies, such as that by Donnelly et al. (2013) showed that this constraint can affect virulence evolution but they had focused on directly transmitted parasites. Using a mathematical model capturing the dynamics of a parasitoid, MacDonald et al. (2021) show if two main assumptions are met, namely that at the end of the season only transmission stages (or “propagules”) survive and that there is a constant decay of these propagules with time, then strains with intermediate levels of virulence are favoured. Practically, the authors use delay differential equations and an adaptive dynamics approach to identify evolutionary stable strategies. As expected, the longer the short the season length, the higher the virulence (because propagule decay matters less). The authors also identify a non-linear relationship between the variation in host development time and virulence. Generally, the larger the variation, the higher the virulence because the parasitoid has to kill its host before the end of the season. However, if the variation is too wide, some hosts become physically impossible to use for the parasite, whence a decrease in virulence. Finally, MacDonald et ali. (2021) show that the consequence of adding trade-offs between infection duration and the number of propagules produced is in line with earlier studies (Ebert and Weisser 1997). These mathematical modelling results provide testable predictions for using well-described systems in evolutionary ecology such as daphnia parasitoids, baculoviruses, or lytic phages. Reference Donnelly R, Best A, White A, Boots M (2013) Seasonality selects for more acutely virulent parasites when virulence is density dependent. Proc R Soc B, 280, 20122464. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2464 Ebert D, Weisser WW (1997) Optimal killing for obligate killers: the evolution of life histories and virulence of semelparous parasites. Proc R Soc B, 264, 985–991. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0136 Levin BR, Lenski RE (1983) Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M eds. Coevolution. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 99–127. Lion S, van Baalen M (2008) Self-structuring in spatial evolutionary ecology. Ecol. Lett., 11, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01132.x MacDonald H, Akçay E, Brisson D (2021) Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites. bioRxiv, 2021.03.13.435259, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.13.435259 | Host phenology can drive the evolution of intermediate virulence strategies in some obligate-killer parasites | Hannelore MacDonald, Erol Akçay, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">The traditional mechanistic trade-offs resulting in a negative correlation between transmission and virulence are the foundation of nearly all current theory on the evolution of parasite virulence. Several ecologica... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Ecology, Evolutionary Epidemiology, Evolutionary Theory | Samuel Alizon | 2021-03-14 13:47:33 | View | |

23 Jun 2021

Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic driftLaurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230Separating adaptation from drift: A cautionary tale from a self-fertilizing plantRecommended by Christoph Haag based on reviews by Pierre Olivier Cheptou, Jon Agren and Stefan LaurentIn recent years many studies have documented shifts in phenology in response to climate change, be it in arrival times in migrating birds, budset in trees, adult emergence in butterflies, or flowering time in annual plants (Coen et al. 2018; Piao et al. 2019). While these changes are, in part, explained by phenotypic plasticity, more and more studies find that they involve also genetic changes, that is, they involve evolutionary change (e.g., Metz et al. 2020). Yet, evolutionary change may occur through genetic drift as well as selection. Therefore, in order to demonstrate adaptive evolutionary change in response to climate change, drift has to be excluded as an alternative explanation (Hansen et al. 2012). A new study by Gay et al. (2021) shows just how difficult this can be. The authors investigated a recent evolutionary shift in flowering time by in a population an annual plant that reproduces predominantly by self-fertilization. The population has recently been subjected to increased temperatures and reduced rainfalls both of which are believed to select for earlier flowering times. They used a “resurrection” approach (Orsini et al. 2013; Weider et al. 2018): Genotypes from the past (resurrected from seeds) were compared alongside more recent genotypes (from more recently collected seeds) under identical conditions in the greenhouse. Using an experimental design that replicated genotypes, eliminated maternal effects, and controlled for microenvironmental variation, they found said genetic change in flowering times: Genotypes obtained from recently collected seeds flowered significantly (about 2 days) earlier than those obtained 22 generations before. However, neutral markers (microsatellites) also showed strong changes in allele frequencies across the 22 generations, suggesting that effective population size, Ne, was low (i.e., genetic drift was strong), which is typical for highly self-fertilizing populations. In addition, several multilocus genotypes were present at high frequencies and persisted over the 22 generations, almost as in clonal populations (e.g., Schaffner et al. 2019). The challenge was thus to evaluate whether the observed evolutionary change was the result of an adaptive response to selection or may be explained by drift alone. Here, Gay et al. (2021) took a particularly careful and thorough approach. First, they carried out a selection gradient analysis, finding that earlier-flowering plants produced more seeds than later-flowering plants. This suggests that, under greenhouse conditions, there was indeed selection for earlier flowering times. Second, investigating other populations from the same region (all populations are located on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, France), they found that a concurrent shift to earlier flowering times occurred also in these populations. Under the hypothesis that the populations can be regarded as independent replicates of the evolutionary process, the observation of concurrent shifts rules out genetic drift (under drift, the direction of change is expected to be random). The study may well have stopped here, concluding that there is good evidence for an adaptive response to selection for earlier flowering times in these self-fertilizing plants, at least under the hypothesis that selection gradients estimated in the greenhouse are relevant to field conditions. However, the authors went one step further. They used the change in the frequencies of the multilocus genotypes across the 22 generations as an estimate of realized fitness in the field and compared them to the phenotypic assays from the greenhouse. The results showed a tendency for high-fitness genotypes (positive frequency changes) to flower earlier and to produce more seeds than low-fitness genotypes. However, a simulation model showed that the observed correlations could be explained by drift alone, as long as Ne is lower than ca. 150 individuals. The findings were thus consistent with an adaptive evolutionary change in response to selection, but drift could only be excluded as the sole explanation if the effective population size was large enough. The study did provide two estimates of Ne (19 and 136 individuals, based on individual microsatellite loci or multilocus genotypes, respectively), but both are problematic. First, frequency changes over time may be influenced by the presence of a seed bank or by immigration from a genetically dissimilar population, which may lead to an underestimation of Ne (Wang and Whitlock 2003). Indeed, the low effective size inferred from the allele frequency changes at microsatellite loci appears to be inconsistent with levels of genetic diversity found in the population. Moreover, high self-fertilization reduces effective recombination and therefore leads to non-independence among loci. This lowers the precision of the Ne estimates (due to a higher sampling variance) and may also violate the assumption of neutrality due to the possibility of selection (e.g., due to inbreeding depression) at linked loci, which may be anywhere in the genome in case of high degrees of self-fertilization. There is thus no definite answer to the question of whether or not the observed changes in flowering time in this population were driven by selection. The study sets high standards for other, similar ones, in terms of thoroughness of the analyses and care in interpreting the findings. It also serves as a very instructive reminder to carefully check the assumptions when estimating neutral expectations, especially when working on species with complicated demographies or non-standard life cycles. Indeed the issues encountered here, in particular the difficulty of establishing neutral expectations in species with low effective recombination, may apply to many other species, including partially or fully asexual ones (Hartfield 2016). Furthermore, they may not be limited to estimating Ne but may also apply, for instance, to the establishment of neutral baselines for outlier analyses in genome scans (see e.g, Orsini et al. 2012). References Cohen JM, Lajeunesse MJ, Rohr JR (2018) A global synthesis of animal phenological responses to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 8, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0067-3 Gay L, Dhinaut J, Jullien M, Vitalis R, Navascués M, Ranwez V, Ronfort J (2021) Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift. bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.261230, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261230 Hansen MM, Olivieri I, Waller DM, Nielsen EE (2012) Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Molecular Ecology, 21, 1311–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05463.x Hartfield M (2016) Evolutionary genetic consequences of facultative sex and outcrossing. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 29, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12770 Metz J, Lampei C, Bäumler L, Bocherens H, Dittberner H, Henneberg L, Meaux J de, Tielbörger K (2020) Rapid adaptive evolution to drought in a subset of plant traits in a large-scale climate change experiment. Ecology Letters, 23, 1643–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13596 Orsini L, Schwenk K, De Meester L, Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Weider LJ (2013) The evolutionary time machine: using dormant propagules to forecast how populations can adapt to changing environments. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.009 Orsini L, Spanier KI, Meester LD (2012) Genomic signature of natural and anthropogenic stress in wild populations of the waterflea Daphnia magna: validation in space, time and experimental evolution. Molecular Ecology, 21, 2160–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05429.x Piao S, Liu Q, Chen A, Janssens IA, Fu Y, Dai J, Liu L, Lian X, Shen M, Zhu X (2019) Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Global Change Biology, 25, 1922–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14619 Schaffner LR, Govaert L, De Meester L, Ellner SP, Fairchild E, Miner BE, Rudstam LG, Spaak P, Hairston NG (2019) Consumer-resource dynamics is an eco-evolutionary process in a natural plankton community. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0960-9 Wang J, Whitlock MC (2003) Estimating Effective Population Size and Migration Rates From Genetic Samples Over Space and Time. Genetics, 163, 429–446. PMID: 12586728 Weider LJ, Jeyasingh PD, Frisch D (2018) Evolutionary aspects of resurrection ecology: Progress, scope, and applications—An overview. Evolutionary Applications, 11, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12563 | Evolution of flowering time in a selfing annual plant: Roles of adaptation and genetic drift | Laurène Gay, Julien Dhinaut, Margaux Jullien, Renaud Vitalis, Miguel Navascués, Vincent Ranwez, and Joëlle Ronfort | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resurrection studies are a useful tool to measure how phenotypic traits have changed in populations through time. If these traits modifications correlate with the environmental changes that occurred during the time ... | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Genotype-Phenotype, Phenotypic Plasticity, Population Genetics / Genomics, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex | Christoph Haag | 2020-08-21 17:26:59 | View | ||

17 May 2021

Relative time constraints improve molecular datingGergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889Dating with constraintsRecommended by Cécile Ané based on reviews by David Duchêne and 1 anonymous reviewerEstimating the absolute age of diversification events is challenging, because molecular sequences provide timing information in units of substitutions, not years. Additionally, the rate of molecular evolution (in substitutions per year) can vary widely across lineages. Accurate dating of speciation events traditionally relies on non-molecular data. For very fast-evolving organisms such as SARS-CoV-2, for which samples are obtained over a time span, the collection times provide this external information from which we can learn the rate of molecular evolution and date past events (Boni et al. 2020). In groups for which the fossil record is abundant, state-of-the-art dating methods use fossil information to complement molecular data, either in the form of a prior distribution on node ages (Nguyen & Ho 2020), or as data modelled with a fossilization process (Heath et al. 2014). Dating is a challenge in groups that lack fossils or other geological evidence, such as very old lineages and microbial lineages. In these groups, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events have been identified as informative about relative dates: the ancestor of the gene's donor must be older than the descendants of the gene's recipient. Previous work using HGTs to date phylogenies have used methodologies that are ad-hoc (Davín et al 2018) or employ a small number of HGTs only (Magnabosco et al. 2018, Wolfe & Fournier 2018). Szöllősi et al. (2021) present and validate a Bayesian approach to estimate the age of diversification events based on relative information on these ages, such as implied by HGTs. This approach is flexible because it is modular: constraints on relative node ages can be combined with absolute age information from fossil data, and with any substitution model of molecular evolution, including complex state-of-art models. To ease the computational burden, the authors also introduce a two-step approach, in which the complexity of estimating branch lengths in substitutions per site is decoupled from the complexity of timing the tree with branch lengths in years, accounting for uncertainty in the first step. Currently, one limitation is that the tree topology needs to be known, and another limitation is that constraints need to be certain. Users of this method should be mindful of the latter when hundreds of constraints are used, as done by Szöllősi et al. (2021) to date the trees of Cyanobacteria and Archaea. Szöllősi et al. (2021)'s method is implemented in RevBayes, a highly modular platform for phylogenetic inference, rapidly growing in popularity (Höhna et al. 2016). The RevBayes tutorial page features a step-by-step tutorial "Dating with Relative Constraints", which makes the method highly approachable. References: Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, Lam TT-Y, Perry BW, Castoe TA, Rambaut A, Robertson DL (2020) Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Microbiology, 5, 1408–1417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4 Davín AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V, Szöllősi GJ (2018) Gene transfers can date the tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0525-3 Heath TA, Huelsenbeck JP, Stadler T (2014) The fossilized birth–death process for coherent calibration of divergence-time estimates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, E2957–E2966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319091111 Höhna S, Landis MJ, Heath TA, Boussau B, Lartillot N, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2016) RevBayes: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference Using Graphical Models and an Interactive Model-Specification Language. Systematic Biology, 65, 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syw021 Magnabosco C, Moore KR, Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Dating phototrophic microbial lineages with reticulate gene histories. Geobiology, 16, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12273 Nguyen JMT, Ho SYW (2020) Calibrations from the Fossil Record. In: The Molecular Evolutionary Clock: Theory and Practice (ed Ho SYW), pp. 117–133. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60181-2_8 Szollosi, G.J., Hoehna, S., Williams, T.A., Schrempf, D., Daubin, V., Boussau, B. (2021) Relative time constraints improve molecular dating. bioRxiv, 2020.10.17.343889, ver. 8 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.343889 Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (2018) Horizontal gene transfer constrains the timing of methanogen evolution. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0513-7 | Relative time constraints improve molecular dating | Gergely J Szollosi, Sebastian Hoehna, Tom A Williams, Dominik Schrempf, Vincent Daubin, Bastien Boussau | <p style="text-align: justify;">Dating the tree of life is central to understanding the evolution of life on Earth. Molecular clocks calibrated with fossils represent the state of the art for inferring the ages of major groups. Yet, other informat... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Genome Evolution, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics | Cécile Ané | 2020-10-21 23:39:17 | View | |

11 May 2021

Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factorsAlexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545Drift rather than host or parasite control can explain within-host Wolbachia growthRecommended by Alison Duncan and Michael Hochberg based on reviews by Simon Fellous and 1 anonymous reviewerWithin-host parasite density is tightly linked to parasite fitness often determining both transmission success and virulence (parasite-induced harm to the host) (Alizon et al., 2009, Anderson & May, 1982). Parasite density may thus be controlled by selection balancing these conflicting pressures. Actual within-host density regulation may be under host or parasite control, or due to other environmental factors (Wale et al., 2019, Vale et al., 2011, Chrostek et al., 2013). Vertically transmitted parasites may also be more vulnerable to drift associated with bottlenecks between generations, which may also determine within-host population size (Mathe-Hubert et al., 2019, Mira & Moran, 2002). Bénard et al. (2021) use 3 experiments to disentangle the role of drift versus host factors in the control of within-host Wolbachia growth in Drosophila melanogaster. They use the wMelPop Wolbachia strain in which virulence (fly longevity) and within-host growth correlate positively with copy number in the genomic region Octomom (Chrostek et al., 2013, Chrostek & Teixeira, 2015). Octomom copy number can be used as a marker for different genetic lineages within the wMelPop strain. In a first experiment, they introgressed and backcrossed this Wolbachia strain into 6 different host genetic backgrounds and show striking differences in within-host symbiont densities which correlate positively with Octomom copy number. This is consistent with host genotype selecting different Wolbachia strains, but also with bottlenecks and drift between generations. To distinguish between these possibilities, they perform 2 further experiments. A second experiment repeated experiment 1, but this time introgression was into 3 independent lines of the Bolivia and USA Drosophila populations; those that, respectively, exhibited the lowest and highest Wolbachia density and Octomom copy number. In this experiment, growth and Octomom copy number were measured across the 3 lines, for each population, after 1, 13 and 25 generations. Although there were little differences between replicates at generation 1, there were differences at generations 13 and 25 among the replicates of both the Bolivia and USA lines. These results are indicative of parasite control, or drift being responsible for within-host growth rather than host factors. A third experiment tested whether Wolbachia density and copy number were under host or parasite control. This was done, again using the USA and Bolivia lines, but this time those from the first experiment, several generations following the initial introgression and backcrossing. The newly introgressed lines were again followed for 25 generations. At generation 1, Wolbachia phenotypes resembled those of the donor parasite population and not the recipient host population indicating a possible maternal effect, but a lack of host control over the parasite. Furthermore, Wolbachia densities and Octomom number differed among replicate lines through time for Bolivia populations and from the donor parasite lines for both populations. These differences among replicate lines that share both host and parasite origins suggest that drift and/or maternal effects are responsible for within-host Wolbachia density and Octomom number. These findings indicate that drift appears to play a role in shaping Wolbachia evolution in this system. Nevertheless, completely ruling out the role of the host or parasite in controlling densities will require further study. The findings of Bénard and coworkers (2021) should stimulate future work on the contribution of drift to the evolution of vertically transmitted parasites. References Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Baalen MV (2009) Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: history, current state of affairs and the future. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x Anderson RM, May RM (1982) Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology, 85, 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000055360 Bénard A, Henri H, Noûs C, Vavre F, Kremer N (2021) Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors. bioRxiv, 2020.11.29.402545, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402545 Chrostek E, Marialva MSP, Esteves SS, Weinert LA, Martinez J, Jiggins FM, Teixeira L (2013) Wolbachia Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in Drosophila melanogaster: A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis. PLOS Genetics, 9, e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003896 Chrostek E, Teixeira L (2015) Mutualism Breakdown by Amplification of Wolbachia Genes. PLOS Biology, 13, e1002065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002065 Mathé‐Hubert H, Kaech H, Hertaeg C, Jaenike J, Vorburger C (2019) Nonrandom associations of maternally transmitted symbionts in insects: The roles of drift versus biased cotransmission and selection. Molecular Ecology, 28, 5330–5346. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15206 Mira A, Moran NA (2002) Estimating Population Size and Transmission Bottlenecks in Maternally Transmitted Endosymbiotic Bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 44, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9 Vale PF, Wilson AJ, Best A, Boots M, Little TJ (2011) Epidemiological, Evolutionary, and Coevolutionary Implications of Context-Dependent Parasitism. The American Naturalist, 177, 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/659002 Wale N, Jones MJ, Sim DG, Read AF, King AA (2019) The contribution of host cell-directed vs. parasite-directed immunity to the disease and dynamics of malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116, 22386–22392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908147116

| Wolbachia load variation in Drosophila is more likely caused by drift than by host genetic factors | Alexis Bénard, Hélène Henri, Camille Noûs, Fabrice Vavre, Natacha Kremer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Symbiosis is a continuum of long-term interactions ranging from mutualism to parasitism, according to the balance between costs and benefits for the protagonists. The density of endosymbionts is, in both cases, a ke... |  | Evolutionary Dynamics, Genetic conflicts, Species interactions | Alison Duncan | 2020-12-01 16:28:14 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

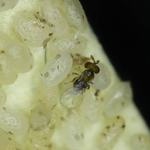

Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host speciesFanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417What makes a parasite successful? Parasitoid wasp venoms evolve rapidly in a host-specific mannerRecommended by Élio Sucena based on reviews by Simon Fellous, alexandre leitão and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitoid wasps have developed different mechanisms to increase their parasitic success, usually at the expense of host survival (Fellowes and Godfray, 2000). Eggs of these insects are deposited inside the juvenile stages of their hosts, which in turn deploy several immune response strategies to eliminate or disable them (Yang et al., 2020). Drosophila melanogaster protects itself against parasitoid attacks through the production of specific elongated haemocytes called lamellocytes which form a capsule around the invading parasite (Lavine and Strand, 2002; Rizki and Rizki, 1992) and the subsequent activation of the phenol-oxidase cascade leading to the release of toxic radicals (Nappi et al., 1995). On the parasitoid side, robust responses have evolved to evade host immune defenses as for example the Drosophila-specific endoparasite Leptopilina boulardi, which releases venom during oviposition that modifies host behaviour (Varaldi et al., 2006) and inhibits encapsulation (Gueguen et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012).

References Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Gatti, J.-L., Colinet, D. and Poirié, M. (2021) Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species. bioRxiv, 2020.10.24.353417, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.24.353417 Cavigliasso, F., Mathé-Hubert, H., Kremmer, L., Rebuf, C., Gatti, J.-L., Malausa, T., Colinet, D., Poiré, M. and Léne. (2019). Rapid and Differential Evolution of the Venom Composition of a Parasitoid Wasp Depending on the Host Strain. Toxins, 11(629). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11110629 Colinet, D., Deleury, E., Anselme, C., Cazes, D., Poulain, J., Azema-Dossat, C., Belghazi, M., Gatti, J. L. and Poirié, M. (2013). Extensive inter- and intraspecific venom variation in closely related parasites targeting the same host: The case of Leptopilina parasitoids of Drosophila. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43(7), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.010 Colinet, D., Dubuffet, A., Cazes, D., Moreau, S., Drezen, J. M. and Poirié, M. (2009). A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 33(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013 Fellowes, M. D. E. and Godfray, H. C. J. (2000). The evolutionary ecology of resistance to parasitoids by Drosophila. Heredity, 84(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00685.x Gueguen, G., Rajwani, R., Paddibhatla, I., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2011). VLPs of Leptopilina boulardi share biogenesis and overall stellate morphology with VLPs of the heterotoma clade. Virus Research, 160(1–2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.005 Lavine, M. D. and Strand, M. R. (2002). Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32(10), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9 Martinez, J., Duplouy, A., Woolfit, M., Vavre, F., O’Neill, S. L. and Varaldi, J. (2012). Influence of the virus LbFV and of Wolbachia in a host-parasitoid interaction. PloS One, 7(4), e35081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035081 Nappi, A. J., Vass, E., Frey, F. and Carton, Y. (1995). Superoxide anion generation in Drosophila during melanotic encapsulation of parasites. European Journal of Cell Biology, 68(4), 450–456. Poirié, M., Colinet, D. and Gatti, J. L. (2014). Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 6, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.004 Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 16(2–3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z Schlenke, T. A., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathogens, 3(10), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030158 Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology, 132(Pt 6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009930 Yang, L., Qiu, L., Fang, Q., Stanley, D. W. and Gong‐Yin, Y. (2020). Cellular and humoral immune interactions between Drosophila and its parasitoids. Insect Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12863

| Parasitic success and venom composition evolve upon specialization of parasitoid wasps to different host species | Fanny Cavigliasso, Hugo Mathé-Hubert, Jean-Luc Gatti, Dominique Colinet, Marylène Poirié | <p>Female endoparasitoid wasps usually inject venom into hosts to suppress their immune response and ensure offspring development. However, the parasitoid’s ability to evolve towards increased success on a given host simultaneously with the evolut... |  | Experimental Evolution, Species interactions | Élio Sucena | 2020-10-26 15:00:55 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang