Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 May 2024

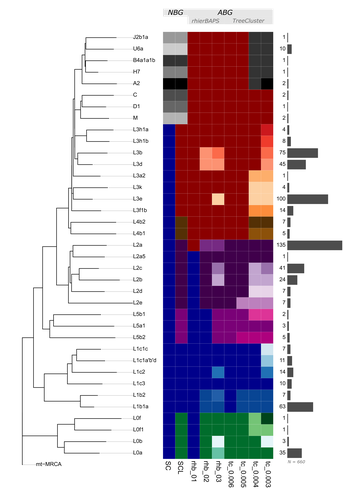

mtDNA "Nomenclutter" and its Consequences on the Interpretation of Genetic DataVladimir Bajić, Vanessa Hava Schulmann, Katja Nowick https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.19.567721Resolving the clutter of naming “Eve’s” descendantsRecommended by Torsten Günther based on reviews by Nicole Huber, Joshua Daniel Rubin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicole Huber, Joshua Daniel Rubin and 1 anonymous reviewer

Nature is complicated and humans often resort to categorization into simplified groups in order to comprehend and manage complex systems. The human mitochondrial genome and its phylogeny are quite complex. Many of those ~16600 base pairs mutated as humans spread across the planet and the resulting phylogeny can be used to illustrate many different aspects of human history and evolution. But it has too many branches and sub-branches to comprehend, which is why major lineages are considered haplogroups. On the highest level, these haplogroups receive capital letters which are then followed by integers and lowercase letters to designate a more fine-scale structure. This nomenclature even inspired semi-fictional literature, such as Bryan Sykes’ “The Seven Daughters of Eve” [1] from 2001 which includes fictional narratives for each of seven “clan mothers” representing seven major European haplogroups (e.g. Helene representing haplogroup H and Tara representing haplogroup T). But apart from categorizing things, humans also like to make exceptions to rules. For instance, not all haplogroup names consist only of letters and numbers but also special characters. And not everything seems logical or intuitive: the deepest split does not include haplogroup A but the most basal lineage is L0. The main letters also do not represent the same level of the tree structure, Sykes’ Katrine representing haplogroup K should not be considered a “daughter of Eve” but (at best) a granddaughter as K is a sub-haplogroup of U (represented by Ursula). This system and the number of haplogroups have not just reached a point where everything has become incredibly complicated despite supposedly simplifying categories. The inherent arbitrariness can also have serious effects on downstream analysis and the interpretation of results depending on how and on what level the authors of a specific study decide to group their individuals. This situation of potential biases introduced through the choice of haplogroup groupings is the motivation for the study by Bajić, Schulmann and Nowick who are using the quite fitting term “nomenclutter” in their title [2]. They are raising an important issue in the inconsistencies introduced by the practice of somewhat arbitrary haplotype groupings which varies across studies and has no common standards in place making comparisons between studies virtually impossible. The study shows that the outcome of certain standard analyses and the interpretation of results are very sensitive to the decision on how to group the different haplotypes. This effect is especially pronounced for populations of African ancestry where the haplotype nomenclature would cut the phylogenetic tree at higher levels and the definition of different lineages is generally more coarse than for other populations. But the authors go beyond pointing out this issue, they also suggest solutions. Instead of grouping sequences by their haplogroup code, one could use “algorithm-based groupings” based on the sequence similarity itself or cutting the phylogenetic tree at a common level of the hierarchy. The analysis of the authors shows that this reduces potential biases substantially. But even such groupings would not be without the influence of the user or researcher’s choices as different parameters have to be set to define the level at which groupings are conducted. The authors propose a neat solution, lifting this issue to be resolved during future updates of the mitochondrial haplogroup nomenclature and the phylogeny. Ideally, the research community could agree on centrally defined haplogroup grouping levels (called “macro-”, “meso-”, and “micro-haplogroups” by the authors) which would all represent different scales of events in human history (from global, continental to local). Classifications like that could be provided through central databases and the classifications could be added to commonly used tools for that purpose. If everyone used these groupings, studies would be a lot more comparable and more fine-scale investigations could still resort to the sequences and the tree itself to avoid all grouping. The experts who reviewed the study have all highlighted its importance of pointing at a very relevant issue. It will take a community effort to improve practices and the current status of this research area. This study provides an important first step and it should be in everyone’s interest to resolve the “nomenclutter”. References 1. Sykes B. (2001) The seven daughters of Eve: the science that reveals our genetic ancestry. 1st American ed. New York: Norton. 2. Bajić V, Schulmann VH, Nowick K. (2024) mtDNA “Nomenclutter” and its Consequences on the Interpretation of Genetic Data. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.19.567721 | mtDNA "Nomenclutter" and its Consequences on the Interpretation of Genetic Data | Vladimir Bajić, Vanessa Hava Schulmann, Katja Nowick | <p style="text-align: justify;">Population-based studies of human mitochondrial genetic diversity often require the classification of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes into more than 5400 described haplogroups, and further grouping those into h... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Human Evolution, Other, Phylogenetics / Phylogenomics, Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Torsten Günther | 2023-11-20 11:16:36 | View | |

05 Apr 2024

Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine populationAlina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.16.545344Weak spatial genetic structure in a large continuous Scots pine population – implications for conservation and breedingRecommended by Myriam Heuertz based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh based on reviews by Joachim Mergeay, Jean-Baptiste Ledoux and Roberta Loh

Spatial genetic structure, i.e. the non-random spatial distribution of genotypes, arises in populations because of different processes including spatially limited dispersal and selection. Knowledge on the spatial genetic structure of plant populations is important to assess biological parameters such as gene dispersal distances and the potential for local adaptations, as well as for applications in conservation management and breeding. In their work, Niskanen and colleagues demonstrate a multifaceted approach to characterise the spatial genetic structure in two replicate sites of a continuously distributed Scots pine population in South-Eastern Finland. They mapped and assessed the ages of 469 naturally regenerated adults and genotyped them using a SNP array which resulted in 157 325 filtered polymorphic SNPs. Their dataset is remarkably powerful because of the large numbers of both individuals and SNPs genotyped. This made it possible to characterise precisely the decay of genetic relatedness between individuals with spatial distance despite the extensive dispersal capacity of Scots pine through pollen, and ensuing expectations of an almost panmictic population. The authors’ data analysis was particularly thorough. They demonstrated that two metrics of pairwise relatedness, the genomic relationship matrix (GRM, Yang et al. 2011) and the kinship coefficient (Loiselle et al. 1995) were strongly correlated and produced very similar inference of family relationships: >99% of pairs of individuals were unrelated, and the remainder exhibited 2nd (e.g., half-siblings) to 4th degree relatedness. Pairwise relatedness decayed with spatial distance which resulted in extremely weak but statistically significant spatial genetic structure in both sites, quantified as Sp=0.0005 and Sp=0.0008. These estimates are at least an order of magnitude lower than estimates in the literature obtained in more fragmented populations of the same species or in other conifers. Estimates of the neighbourhood size, the effective number of potentially mating individuals belonging to a within-population neighbourhood (Wright 1946), were relatively large with Nb=1680-3210 despite relatively short gene dispersal distances, σg = 36.5–71.3m, which illustrates the high effective density of the population. The authors showed the implications of their findings for selection. The capacity for local adaptation depends on dispersal distances and the strength of the selection coefficient. In the study population, the authors inferred that local adaptation can only occur if environmental heterogeneity occurs over a distance larger than approximately one kilometre (or larger, if considering long-distance dispersal). Interestingly, in Scots pine, no local adaptation has been described on similar geographic scales, in contrast to some other European or Mediterranean conifers (Scotti et al. 2023). The authors’ results are relevant for the management of conservation and breeding. They showed that related individuals occurred within sites only and that they shared a higher number of rare alleles than unrelated ones. Since rare alleles are enriched in new and recessive deleterious variants, selecting related individuals could have negative consequences in breeding programmes. The authors also showed, in their response to reviewers, that their powerful dataset was not suitable to obtain a robust estimate of effective population size, Ne, based on the linkage disequilibrium method (Do et al. 2014). This illustrated that the estimation of Ne used for genetic indicators supported in international conservation policy (Hoban et al. 2020, CBD 2022) remains challenging in large and continuous populations (see also Santo-del-Blanco et al. 2023, Gargiulo et al. 2024). ReferencesCBD (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014). NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne ) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12157 Gargiulo R, Decroocq V, González-Martínez SC, Paz-Vinas I, Aury JM, Kupin IL, Plomion C, Schmitt S, Scotti I, Heuertz M (2024) Estimation of contemporary effective population size in plant populations: limitations of genomic datasets. Evolutionary Applications, in press, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549323 Hoban S, Bruford M, D’Urban Jackson J, Lopes-Fernandes M, Heuertz M, Hohenlohe PA, Paz-Vinas I, et al. (2020) Genetic diversity targets and indicators in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework must be improved. Biological Conservation 248: 108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108654 Loiselle BA, Sork VL, Nason J & Graham C (1995) Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understorey shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb12679.x Santos-del-Blanco L, Olsson S, Budde KB, Grivet D, González-Martínez SC, Alía R, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ (2022). On the feasibility of estimating contemporary effective population size (Ne) for genetic conservation and monitoring of forest trees. Biological Conservation 273: 109704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109704 Scotti I, Lalagüe H, Oddou-Muratorio S, Scotti-Saintagne C, Ruiz Daniels R, Grivet D, et al. (2023) Common microgeographical selection patterns revealed in four European conifers. Molecular Ecology 32: 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16750 Wright S (1946) Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics 31: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/31.1.39 Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME & Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88: 76–82. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/pdf/S0002-9297(10)00598-7.pdf | Does the seed fall far from the tree? Weak fine scale genetic structure in a continuous Scots pine population | Alina K. Niskanen, Sonja T. Kujala, Katri Kärkkäinen, Outi Savolainen, Tanja Pyhäjärvi | <p>Knowledge of fine-scale spatial genetic structure, i.e., the distribution of genetic diversity at short distances, is important in evolutionary research and in practical applications such as conservation and breeding programs. In trees, related... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Applications, Population Genetics / Genomics | Myriam Heuertz | Joachim Mergeay | 2023-06-27 21:57:28 | View |

28 Mar 2024

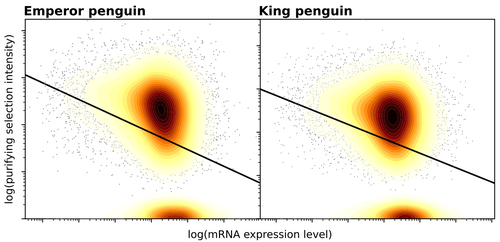

Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populationsEmiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445Purifying selection on highly expressed genes in PenguinsRecommended by Bruce Rannala based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tanja Pyhäjärvi and 1 anonymous reviewer

Given the general importance of protein expression levels, in cells it is widely accepted that gene expression levels are often a target of natural selection and that most mutations affecting gene expression levels are therefore likely to be deleterious [1]. However, it is perhaps less obvious that the strength of selection on the regulated genes themselves may be influenced by their expression levels. This might be due to harmful effects of misfolded proteins, for example, when higher protein concentrations exist in cells [2]. Recent studies have suggested that highly expressed genes accumulate fewer deleterious mutations; thus a positive relationship appears to exist between gene expression levels and the relative strength of purifying selection [3]. The recommended paper by Trucchi et al. [4] examines the relationship between gene expression, purifying selection and a third variable -- effective population size -- in populations of two species of penguin with different population sizes, the Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) and the King penguin (A. patagonicus). Using transcriptomic data and computer simulations modeling selection, they examine patterns of nonsynonymous and synonymous segregating polymorphisms (p) across genes in the two populations, concluding that even in relatively small populations purifying selection has an important effect in eliminating deleterious mutations. References 1] Gilad Y, Oshlack A, and Rifkin SA. 2006. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends in Genetics 22: 456-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002 [4] Trucchi E, Massa P, Giannelli F, Latrille T, Fernandes FAN, Ancona L, Stenseth NC, Obiol JF, Paris J, Bertorelle G, and Le Bohec, C. 2023. Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations. bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552445, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552445

| Gene expression is the main driver of purifying selection in large penguin populations | Emiliano Trucchi, Piergiorgio Massa, Francesco Giannelli, Thibault Latrille, Flavia A.N. Fernandes, Lorena Ancona, Nils Chr Stenseth, Joan Ferrer Obiol, Josephine Paris, Giorgio Bertorelle, Celine Le Bohec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Purifying selection is the most pervasive type of selection, as it constantly removes deleterious mutations arising in populations, directly scaling with population size. Highly expressed genes appear to accumulate ... |  | Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Dynamics, Evolutionary Theory, Population Genetics / Genomics | Bruce Rannala | 2023-08-09 17:53:03 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

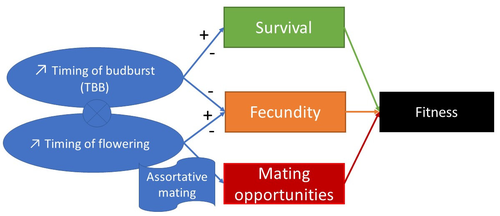

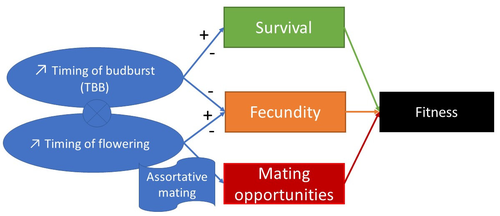

Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.).Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Recommended by Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Starting with the seminar paper by Lande & Arnold (1983), several studies have addressed phenotypic selection in natural populations of a wide variety of organisms, with a recent renewed interest in forest trees (e.g., Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2018; Alexandre et al. 2020; Westergren et al. 2023). Because of their long generation times, long-lived organisms such as forest trees may suffer the most from maladaptation due to climate change, and whether they will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions in just one or a few generations is hotly debated. In this study, Oddou-Muratorio and colleagues (2024) extend the current framework to add two additional selection components that may alter patterns of fecundity selection and the estimation of standard selection gradients, namely sexual selection (evaluated as differences in flowering phenology conducting to assortative mating) and growth (viability) selection. Notably, the study is conducted in two contrasted environments (low vs high altitude populations) providing information on how the environment may modulate selection patterns in spring phenology. Spring phenology is a key adaptive trait that has been shown to be already affected by climate change in forest trees (Alberto et al. 2013). While fecundity selection for early phenology has been extensively reported before (see Munguía-Rosas et al. 2011), the authors found that this kind of selection can be strongly modulated by sexual selection, depending on the environment. Moreover, they found a significant correlation between early phenology and seedling growth in a common garden, highlighting the importance of this trait for early survival in European beech. As a conclusion, this original research puts in evidence the need for more integrative approaches for the study of natural selection in the field, as well as the importance of testing multiple environments and the relevance of common gardens to further evaluate phenotypic changes due to real-time selection. PS: The recommender and the first author of the preprint have shared authorship in a recent paper in a similar topic (Westergren et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the recommender has not contributed in any way or was aware of the content of the current preprint before acting as recommender, and steps have been taken for a fair and unpartial evaluation. References Alberto, F. J., Aitken, S. N., Alía, R., González‐Martínez, S. C., Hänninen, H., Kremer, A., Lefèvre, F., Lenormand, T., Yeaman, S., Whetten, R., & Savolainen, O. (2013). Potential for evolutionary responses to climate change - evidence from tree populations. Global Change Biology, 19(6), 1645‑1661. Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Gauzere J, Klein E (2024) Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538521, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538521 Oddou-Muratorio, S., Gauzere, J., Bontemps, A., Rey, J.-F., & Klein, E. K. (2018). Tree, sex and size: Ecological determinants of male vs. female fecundity in three Fagus sylvatica stands. Molecular Ecology, 27(15), 3131‑3145. | Interplay between fecundity, sexual and growth selection on the spring phenology of European beech (*Fagus sylvatica* L.). | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Aurore Bontemps, Julie Gauzere, Etienne Klein | <p>Background: Plant phenological traits such as the timing of budburst or flowering can evolve on ecological timescales through response to fecundity and viability selection. However, interference with sexual selection may arise from assortative ... |  | Adaptation, Evolutionary Ecology, Quantitative Genetics, Reproduction and Sex, Sexual Selection | Santiago C. Gonzalez-Martinez | 2023-05-02 11:57:23 | View | |

04 Mar 2024

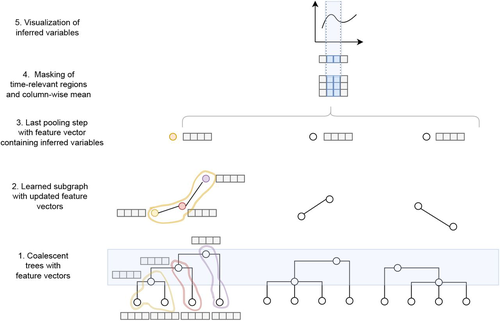

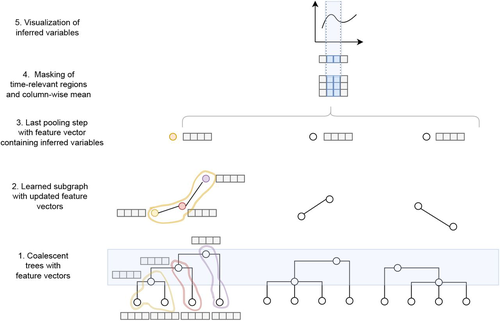

Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta CoalescentKevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.28.508873Beyond the standard coalescent: demographic inference with complete genomes and graph neural networks under the beta coalescentRecommended by Julien Yann Dutheil based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Modelling the evolution of complete genome sequences in populations requires accounting for the recombination process, as a single tree can no longer describe the underlying genealogy. The sequentially Markov coalescent (SMC, McVean and Cardin 2005; Marjoram and Wall 2006) approximates the standard coalescent with recombination process and permits estimating population genetic parameters (e.g., population sizes, recombination rates) using population genomic datasets. As such datasets become available for an increasing number of species, more fine-tuned models are needed to encompass the diversity of life cycles of organisms beyond the model species on which most methods have been benchmarked. The work by Korfmann et al. (Korfmann et al. 2024) represents a significant step forward as it accounts for multiple mergers in SMC models. Multiple merger models account for simultaneous coalescence events so that more than two lineages find a common ancestor in a given generation. This feature is not allowed in standard coalescent models and may result from selection or skewed offspring distributions, conditions likely met by a broad range of species, particularly microbial. Yet, this work goes beyond extending the SMC, as it introduces several methodological innovations. The "classical" SMC-based inference approaches rely on hidden Markov models to compute the likelihood of the data while efficiently integrating over the possible ancestral recombination graphs (ARG). Following other recent works (e.g. Gattepaille et al. 2016), Korfmann et al. propose to separate the ARG inference from model parameter estimation under maximum likelihood (ML). They introduce a procedure where the ARG is first reconstructed from the data and then taken as input in the model fitting step. While this approach does not permit accounting for the uncertainty in the ARG reconstruction (which is typically large), it potentially allows for the extraction of more information from the ARG, such as the occurrence of multiple merging events. Going away from maximum likelihood inference, the authors trained a graph neural network (GNN) on simulated ARGs, introducing a new, flexible way to estimate population genomic parameters. The authors used simulations under a beta-coalescent model with diverse demographic scenarios and showed that the ML and GNN approaches introduced can reliably recover the simulated parameter values. They further show that when the true ARG is given as input, the GNN outperforms the ML approach, demonstrating its promising power as ARG reconstruction methods improve. In particular, they showed that trained GNNs can disentangle the effects of selective sweeps and skewed offspring distributions while inferring past population size changes. This work paves the way for new, exciting applications, though many questions must be answered. How frequent are multiple mergers? As the authors showed that these events "erase" the record of past demographic events, how many genomes are needed to conduct reliable inference, and can the methods computationally cope with the resulting (potentially large) amounts of required data? This is particularly intriguing as micro-organisms, prone to strong selection and skewed offspring distributions, also tend to carry smaller genomes. References Gattepaille L, Günther T, Jakobsson M. 2016. Inferring Past Effective Population Size from Distributions of Coalescent Times. Genetics 204:1191-1206. | Simultaneous Inference of Past Demography and Selection from the Ancestral Recombination Graph under the Beta Coalescent | Kevin Korfmann, Thibaut Sellinger, Fabian Freund, Matteo Fumagalli, Aurélien Tellier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The reproductive mechanism of a species is a key driver of genome evolution. The standard Wright-Fisher model for the reproduction of individuals in a population assumes that each individual produces a number of off... |  | Adaptation, Bioinformatics & Computational Biology, Evolutionary Applications, Evolutionary Theory, Life History, Population Genetics / Genomics | Julien Yann Dutheil | 2023-07-31 13:11:22 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident speciesElodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987The evolution of a hobo snailRecommended by Ben Phillips based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by David Reznick and 2 anonymous reviewers

At the very end of a paper entitled "Copepodology for the ornithologist" Hutchinson (1951) pointed out the possibility of 'fugitive species'. A fugitive species, said Hutchinson, is one that we would typically think of as competitively inferior. Wherever it happens to live it will eventually be overwhelmed by competition from another species. We would expect it to rapidly go extinct but for one reason: it happens to be a much better coloniser than the other species. Now all we need to explain its persistence is a dose of space and a little disturbance: a world in which there are occasional disturbances that cause local extinction of the dominant species. Now, argued Hutchinson, we have a recipe for persistence, albeit of a harried kind. As Hutchinson put it, fugitive species "are forever on the move, always becoming extinct in one locality as they succumb to competition, and always surviving as they reestablish themselves in some other locality." It is a fascinating idea, not just because it points to an interesting strategy, but also because it enriches our idea of competition: competition for space can be just as important as competition for time. Hutchinson's idea was independently discovered with the advent of metapopulation theory (Levins 1971; Slatkin 1974) and since then, of course, ecologists have gone looking, and they have unearthed many examples of species that could be said to have a fugitive lifestyle. These fugitive species are out there, but we don't often get to see them evolve. In their recent paper, Chapuis et al. (2024) make a convincing case that they have seen the evolution of a fugitive species. They catalog the arrival of an invasive freshwater snail on Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, and they wonder what impact this snail's arrival might have on a native freshwater snail. This is a snail invasion, so it has been proceeding at a majestic pace, allowing the researchers to compare populations of the native snail that are completely naive to the invader with those that have been exposed to the invader for either a relatively short period (<20 generations) or longer periods (>20 generations). They undertook an extensive set of competition assays on these snails to find out which species were competitively superior and how the native species' competitive ability has evolved over time. Against naive populations of the native, the invasive snail turns out to be unequivocally the stronger competitor. (This makes sense; it probably wouldn't have been able to invade if it wasn't.) So what about populations of the native snail that have been exposed for longer, that have had time to adapt? Surprisingly these populations appear to have evolved to become even weaker competitors than they already were. So why is it that the native species has not simply been driven extinct? Drawing on their previous work on this system, the authors can explain this situation. The native species appears to be the better coloniser of new habitats. Thus, it appears that the arrival of the invasive species has pushed the native species into a different place along the competition-colonisation axis. It has sacrificed competitive ability in favour of becoming a better coloniser; it has become a fugitive species in its own backyard. This is a really nice empirical study. It is a large lab study, but one that makes careful sampling around a dynamic field situation. Thus, it is a lab study that informs an earlier body of fieldwork and so reveals a fascinating story about what is happening in the field. We are left not only with a particularly compelling example of character displacement towards a colonising phenotype but also with something a little less scientific: the image of a hobo snail, forever on the run, surviving in the spaces in between. References Chapuis E, Jarne P, David P (2024) Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species. bioRxiv, 2023.10.25.563987, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.25.563987 Hutchinson, G.E. (1951) Copepodology for the Ornithologist. Ecology 32: 571–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1931746 Levins, R., and D. Culver. (1971) Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 68, no. 6: 1246–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246. Slatkin, Montgomery. (1974) Competition and Regional Coexistence. Ecology 55, no. 1: 128–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934625. | Rapid life-history evolution reinforces competitive asymmetry between invasive and resident species | Elodie Chapuis, Philippe Jarne, Patrice David | <p style="text-align: justify;">Biological invasions by phylogenetically and ecologically similar competitors pose an evolutionary challenge to native species. Cases of character displacement following invasions suggest that they can respond to th... |  | Evolutionary Ecology, Life History, Species interactions | Ben Phillips | 2023-10-26 15:49:33 | View | |

23 Feb 2024

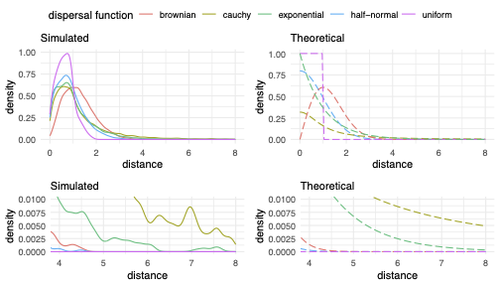

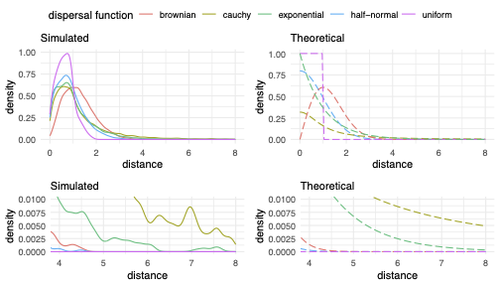

Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequencesMariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388Disentangling the impact of mating and competition on dispersal patternsRecommended by Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo based on reviews by Anthony Wilder Wohns, Christian Huber and 2 anonymous reviewersSpatial population genetics is a field that studies how different evolutionary processes shape geographical patterns of genetic variation. This field is currently hampered by the lack of a deep understanding of the impact of different evolutionary processes shaping the genetic diversity observed across a continuous space (Bradburd and Ralph 2019). Luckily, the recent development of slendr (Petr et al. 2023), which uses the simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer 2023), provides a powerful tool to perform simulations to analyze the impact of different evolutionary parameters on spatial patterns of genetic variation. Here, Ianni-Ravn, Petr, and Racimo 2023 present a series of well-designed simulations to study how three evolutionary factors (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) shape the geographical structure of genealogies. The authors model the dispersal distance between parents and their offspring using five different distributions. Then, the authors perform simulations and they contrast the correspondence between the distribution of observed parent-offspring distances (called DD in the paper) and the distribution used in the simulations (called DF). The authors observe a reasonable correspondence between DF and DD. The authors then show that the competition distance, which decreases the fitness of individuals due to competition for resources if the individuals are close to each other, has small effects on the differences between DD and DF. In contrast, the mate choice distance (which specifies how far away can a parent go to choose a mate) causes discrepancies between DD and DF. When the mate choice distance is small, the individuals tend to cluster close to each other. Overall, these results show that the observed distances between parents and offspring are dependent on the three parameters inspected (dispersal distance, competition distance, and mate choice distance) and make the case that further ecological knowledge of each of these parameters is important to determine the processes driving the dispersal of individuals across geographical space. Based on these results, the authors argue that an “effective dispersal distance” parameter, which takes into account the impact of mate choice distance and dispersal distance, is more prone to be inferred from genetic data. The authors also assess our ability to estimate the dispersal distance using genealogical data in a scenario where the mating distance has small effects on the dispersal distance. Interestingly, the authors show that accurate estimates of the dispersal distance can be obtained when using information from all the parents and offspring going from the present back to the coalescence of all the individuals to the most recent common ancestor. On the other hand, the estimates of the dispersal distance are underestimated when less information from the parent-offspring relationships is used to estimate the dispersal distance. This paper shows the importance of considering mating patterns and the competition for resources when analyzing the dispersal of individuals. The analysis performed by the authors backs up this claim with carefully designed simulations. I recommend this preprint because it makes a strong case for the consideration of ecological factors when analyzing the structure of genealogies and the dispersal of individuals. Hopefully more studies in the future will continue to use simulations and to develop analytical theory to understand the importance of various ecological processes driving spatial genetic variation changes. Bradburd, Gideon S., and Peter L. Ralph. 2019. “Spatial Population Genetics: It’s About Time.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50 (1): 427–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022659. Haller, Benjamin C., and Philipp W. Messer. 2023. “SLiM 4: Multispecies Eco-Evolutionary Modeling.” The American Naturalist 201 (5): E127–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/723601. Ianni-Ravn, Mariadaria K., Martin Petr, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Ecological Parameters on the Spatial Structure of Genealogies.” bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.27.534388. Petr, Martin, Benjamin C. Haller, Peter L. Ralph, and Fernando Racimo. 2023. “Slendr: A Framework for Spatio-Temporal Population Genomic Simulations on Geographic Landscapes.” Peer Community Journal 3 (e121). https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.354. | Exploring the effects of ecological parameters on the spatial structure of genetic tree sequences | Mariadaria K. Ianni-Ravn, Martin Petr, Fernando Racimo | <p>Geographic space is a fundamental dimension of evolutionary change, determining how individuals disperse and interact with each other. Consequently, space has an important influence on the structure of genealogies and the distribution of geneti... |  | Phylogeography & Biogeography, Population Genetics / Genomics | Diego Ortega-Del Vecchyo | 2023-03-31 18:21:02 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structureJun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Illera, Miriam Liedvogel https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882Discerning the causes of local deviations in genetic variation: the effect of low-recombination regionsRecommended by Matteo Fumagalli based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Claire Merot and 1 anonymous reviewer

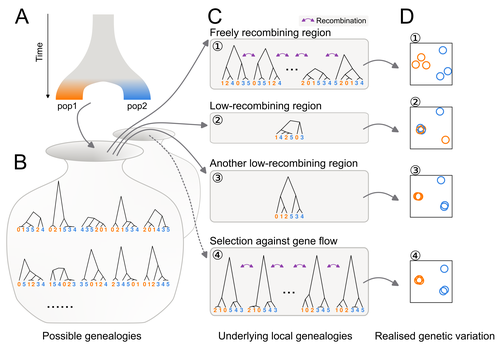

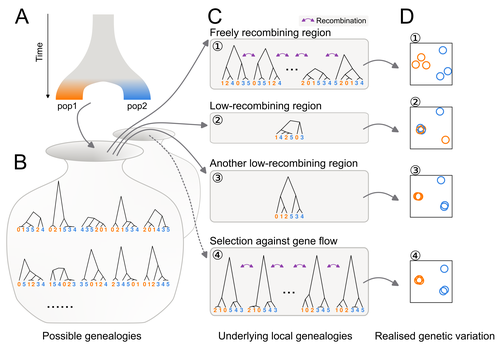

In this study, Ishigohoka and colleagues tackle an important, yet often overlooked, question on the causes of genetic variation. While genome-wide patterns represent population structure, local variation is often associated with selection. Authors propose that an alternative cause for variation in individual loci is reduced recombination rate. To test this hypothesis, authors perform local Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Li & Ralph, 2019) to identify local deviations in population structure in the Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). This approach is typically used to detect chromosomal rearrangements or any long region of linked loci (e.g., due to reduced recombination or selection) (Mérot et al. 2021). While other studies investigated the effect of low recombination on genetic variation (Booker et al. 2020), here authors provide a comprehensive analysis of the effect of recombination to local PCA patterns both in empirical and simulated data sets. Findings demonstrate that low recombination (and not selection) can be the sole explanatory variable for outlier windows. The study also describes patterns of genetic variation along the genome of Eurasian blackcaps, localising at least two polymorphic inversions (Ishigohoka et al. 2022). Further investigations on the effect of model parameters (e.g., window sizes and thresholds for defining low-recombining regions), as well as the use of powerful neutrality tests are in need to clearly assess whether outlier regions experience selection and reduced recombination, and to what extent. References Booker, T. R., Yeaman, S., & Whitlock, M. C. (2020). Variation in recombination rate affects detection of outliers in genome scans under neutrality. Molecular Ecology, 29 (22), 4274–4279. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15501 Ishigohoka, J., Bascón-Cardozo, K., Bours, A., Fuß, J., Rhie, A., Mountcastle, J., Haase, B., Chow, W., Collins, J., Howe, K., Uliano-Silva, M., Fedrigo, O., Jarvis, E. D., Pérez-Tris, J., Illera, J. C., Liedvogel, M. (2022) Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure. bioRxiv 2021.12.22.473882, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.22.473882 Li, H., & Ralph, P. (2019). Local PCA Shows How the Effect of Population Structure Differs Along the Genome. Genetics, 211 (1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.118.301747 Mérot, C., Berdan, E. L., Cayuela, H., Djambazian, H., Ferchaud, A.-L., Laporte, M., Normandeau, E., Ragoussis, J., Wellenreuther, M., & Bernatchez, L. (2021). Locally Adaptive Inversions Modulate Genetic Variation at Different Geographic Scales in a Seaweed Fly. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38 (9), 3953–3971. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab143 | Distinct patterns of genetic variation at low-recombining genomic regions represent haplotype structure | Jun Ishigohoka, Karen Bascón-Cardozo, Andrea Bours, Janina Fuß, Arang Rhie, Jacquelyn Mountcastle, Bettina Haase, William Chow, Joanna Collins, Kerstin Howe, Marcela Uliano-Silva, Olivier Fedrigo, Erich D. Jarvis, Javier Pérez-Tris, Juan Carlos Il... | <p>Genetic variation of the entire genome represents population structure, yet individual loci can show distinct patterns. Such deviations identified through genome scans have often been attributed to effects of selection instead of randomness. Th... |  | Genome Evolution, Molecular Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics | Matteo Fumagalli | 2023-10-13 11:58:47 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks?Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.550272How to survive the mutational meltdown: lessons from plant RNA virusesRecommended by Kavita Jain based on reviews by Brent Allman, Ana Morales-Arce and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough most mutations are deleterious, the strongly deleterious ones do not spread in a very large population as their chance of fixation is very small. Another mechanism via which the deleterious mutations can be eliminated is via recombination or sexual reproduction. However, in a finite asexual population, the subpopulation without any deleterious mutation will eventually acquire a deleterious mutation resulting in the reduction of the population size or in other words, an increase in the genetic drift. This, in turn, will lead the population to acquire deleterious mutations at a faster rate eventually leading to a mutational meltdown. This irreversible (or, at least over some long time scales) accumulation of deleterious mutations is especially relevant to RNA viruses due to their high mutation rate, and while the prior work has dealt with bacteriophages and RNA viruses, the study by Lafforgue et al. [1] makes an interesting contribution to the existing literature by focusing on plants. In this study, the authors enquire how despite the repeated increase in the strength of genetic drift, how the RNA viruses manage to survive in plants. Following a series of experiments and some numerical simulations, the authors find that as expected, after severe bottlenecks, the fitness of the population decreases significantly. But if the bottlenecks are followed by population expansion, the Muller’s ratchet can be halted due to the genetic diversity generated during population growth. They hypothesize this mechanism as a potential way by which the RNA viruses can survive the mutational meltdown. As a theoretician, I find this investigation quite interesting and would like to see more studies addressing, e.g., the minimum population growth rate required to counter the potential extinction for a given bottleneck size and deleterious mutation rate. Of course, it would be interesting to see in future work if the hypothesis in this article can be tested in natural populations. References [1] Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena (2024) How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology | How do plant RNA viruses overcome the negative effect of Muller s ratchet despite strong transmission bottlenecks? | Guillaume Lafforgue, Marie Lefebvre, Thierry Michon, Santiago F. Elena | <p>Muller's ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in small populations, resulting in a decline in overall fitness. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in experiments involving microorganisms, including ... | Experimental Evolution, Genome Evolution | Kavita Jain | 2023-08-04 09:37:08 | View | ||

06 Feb 2024

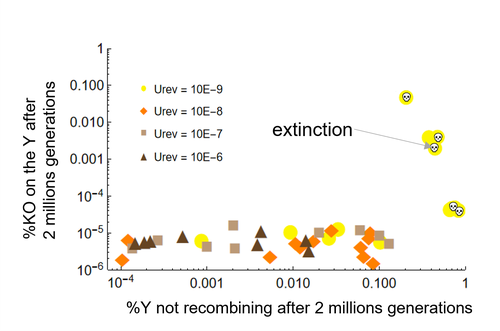

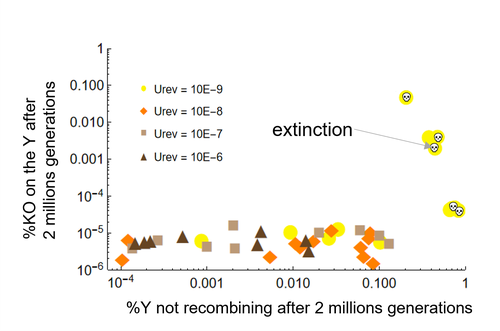

Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes?Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.17.528909New modelling results help understanding the evolution and maintenance of recombination suppression involving sex chromosomesRecommended by Jos Käfer based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite advances in genomic research, many views of genome evolution are still based on what we know from a handful of species, such as humans. This also applies to our knowledge of sex chromosomes. We've apparently been too much used to the situation in which a highly degenerate Y chromosome coexists with an almost normal X chromosome to be able to fully grasp all the questions implied by this situation. Lately, many more sex chromosomes have been studied in other organisms, such as in plants, and the view is changing radically: there is a large diversity of situations, ranging from young highly divergent sex chromosomes to old ones that are so similar that they're hard to detect. Undoubtedly inspired by these recent findings, a few theoretical studies have been published around 2 years ago that put an entirely new light on the evolution of sex chromosomes. The differences between these models have however remained somewhat difficult to appreciate by non-specialists. In particular, the models by Lenormand & Roze (2022) and by Jay et al. (2022) seemed quite similar. Indeed, both rely on the same mechanism for initial recombination suppression: a ``lucky'' inversion, i.e. one with less deleterious mutations than the population average, encompassing the sex-determination locus, is initially selected. However, as it doesn't recombine, it will quickly accumulate deleterious mutations lowering its fitness. And it's at this point the models diverge: according to Lenormand & Roze (2022), nascent dosage compensation not only limits the deleterious effects on fitness by the ongoing degeneration, but it actually opposes recombination restoration as this would lead gene expression away from the optimum that has been reached. On the other hand, in the model by Jay et al. (2022), no additional ingredient is required: they argue that once an inversion had been fixed, reversions that restore recombination are extremely unlikely. This is what Lenormand & Roze (2024) now call a ``constraint'': in Jay et al.'s model, recombination restoration is impossible for mechanistic reasons. Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue such constraints cannot explain long-term recombination suppression. Instead, a mechanism should evolve to limit the negative fitness effects of recombination arrest, otherwise recombination is either restored, or the population goes extinct due to a dramatic drop in the fitness of the heterogametic sex. These two arguments work together: given the huge fitness cost of the lack of ongoing degeneration of the non-recombining Y, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms, there is a very strong selection for the restoration of recombination, so that even when restoration a priori is orders of magnitude less likely than inversion (leading to recombination suppression), it will eventually happen. One way the negative fitness effects of recombination suppression can be limited, is the way the authors propose in their own model: dosage compensation evolves through regulatory evolution right at the start of recombination suppression. This changes our classical, simplistic view that dosage compensation evolves in response to degeneration: rather, Lenormand & Roze (2024) argue, that degeneration can only happen when dosage compensation is effective. The reasoning is convincing and exposes the difference between the models to readers without a firm background in mathematical modelling. Although Lenormand & Roze (2024) target the "constraint theory", it seems likely that other theories for the maintenance of recombination suppression that don't imply the compensation of early degeneration are subject to the same criticism. Indeed, they mention the widely-cited "sexual antagonism" theory, in which mutations with a positive effect in males but a negative in females will select for recombination suppression that will link them to the sex-determining gene on the Y. However, once degeneration starts, the sexually-antagonistic benefits should be huge to overcome the negative effects of degeneration, and it's unlikely they'll be large enough. A convincing argument by Lenormand & Roze (2024) is that there are many ways recombination could be restored, allowing to circumvent the possible constraints that might be associated with reverting an inversion. First, reversions don't have to be exact to restore recombination. Second, the sex-determining locus can be transposed to another chromosome pair, or an entirely new sex-determining locus might evolve, leading to sex-chromosome turnover which has effectively been observed in several groups. These modelling studies raise important questions that need to be addressed with both theoretical and empirical work. First, is the regulatory hypothesis proposed by Lenormand & Roze (2022) the only plausible mechanism for the maintenance of long-term recombination suppression? The female- and male-specific trans regulators of gene expression that are required for this model, are they readily available or do they need to evolve first? Both theoretical work and empirical studies of nascent sex chromosomes will help to answer these questions. However, nascent sex chromosomes are difficult to detect and dosage compensation is difficult to reveal. Second, how many species today actually have "stable" recombination suppression? Maybe many species are in a transient phase, with different populations having different inversions that are either on their way to being fixed or starting to get counterselected. The models have now shown us some possibilities qualitatively but can they actually be quantified to be able to fit the data and to predict whether an observed case of recombination suppression is transient or stable? The debate will continue, and we need the active contribution of theoretical biologists to help clarify the underlying hypotheses of the proposed mechanisms. Conflict of interest statement: I did co-author a manuscript with D. Roze in 2023, but do not consider this a conflict of interest. The manuscript is the product of discussions that have taken place in a large consortium mainly in 2019. It furthermore deals with an entirely different topic of evolutionary biology. References Jay P, Tezenas E, Véber A, and Giraud T. (2022) Sheltering of deleterious mutations explains the stepwise extension of recombination suppression on sex chromosomes and other supergenes. PLoS Biol.;20:e3001698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001698 | Can mechanistic constraints on recombination reestablishment explain the long-term maintenance of degenerate sex chromosomes? | Thomas Lenormand, Denis Roze | <p style="text-align: justify;">Y and W chromosomes often stop recombining and degenerate. Most work on recombination suppression has focused on the mechanisms favoring recombination arrest in the short term. Yet, the long-term maintenance of reco... |  | Evolutionary Theory, Genome Evolution, Population Genetics / Genomics, Reproduction and Sex | Jos Käfer | 2023-10-27 21:52:06 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Dustin Brisson

Julien Dutheil

Marianne Elias

Inês Fragata

François Rousset

Sishuo Wang